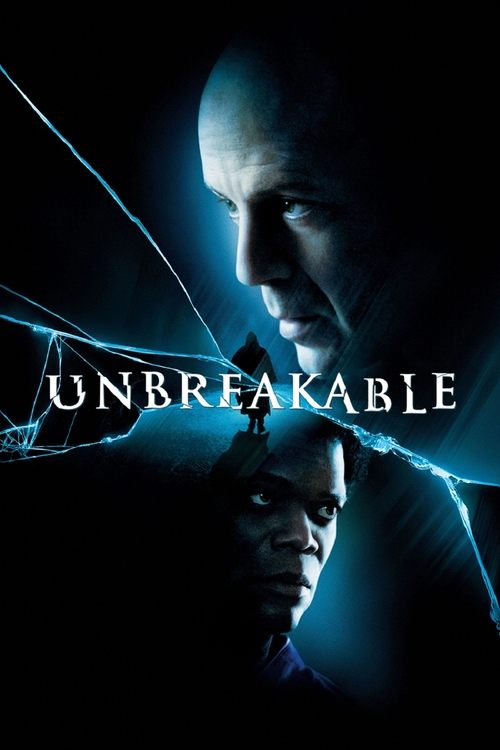

Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

In 1961, in a cramped fitting room of a Philadelphia department store, a woman goes into labor. The fluorescent lights are harsh, reflecting off the mirrors and chrome hooks as clerks scramble to make space. When the baby is born, the room fills with an uneasy silence instead of joy. Doctors examine the newborn boy, tiny and still on the changing table, and their faces harden. His arms and legs bend at odd angles. They are already broken.

The doctor tells the stunned mother that her child, Elijah Price, has a rare condition--his bones break with almost no force. He tries to be clinical, but horror seeps into his voice as he explains that Elijah's skeleton is like glass. The mother's eyes fill, yet she doesn't turn away. She touches her son's face with trembling fingers, promising him softly that she will protect him, that his life will still have meaning. The boy cries, a fragile sound in a room that suddenly feels too small.

Elijah's childhood becomes a sequence of brittle moments and hospital corridors. Each time he ventures into the world, something breaks--an arm from a bump on the playground, a leg from a misstep on a stair. He spends long stretches staring at white ceilings, bound in plaster and gauze. Outside, other children run and play; inside, Elijah watches through windows and television screens. He grows afraid of the world, of doorknobs and sidewalks, of anything that might send him back to the emergency room.

His mother refuses to let fear imprison him completely. One day, when he is still a small boy who prefers to sit alone inside their apartment, she devises a ritual. She leaves a wrapped comic book on a park bench across the street, where Elijah can see it from their window. She tells him there is something special waiting for him outside if he is brave enough to go. He hesitates, staring at the door as if it might explode at a touch. Then he limps across the room, opens it, and ventures outside. Each step is a risk. He reaches the bench, unwraps the comic, and sees vivid artwork--bold colors, men in capes, villains in dramatic poses.

Later she tells him, with solemn pride, that comic books are a form of art, stories about who we are at our deepest levels. She treats them like sacred texts, pointing at the splash panels and explaining how the hero and villain are reflections of each other, opposites in perfect balance. Elijah drinks in her words. If someone like him exists--someone so weak and breakable--he begins to wonder who must be at the other end of that spectrum. The idea settles inside him and hardens into conviction: somewhere out there, there must be someone who cannot break at all.

Years pass. Philadelphia changes, the fashion and cars and storefronts shifting, but Elijah's reality remains the same: glass bones, hospitals, and comic books. He grows into a man of fine suits and careful, deliberate movements, his body fragile but his mind sharp. The belief his mother planted becomes his guiding philosophy. If the world contains a man made of glass, then it must also contain his opposite. And if such a person exists, Elijah will find him--no matter the cost.

Across the city, in a different time, a boy named David Dunn grows up with the solidity Elijah lacks. David is broad-shouldered, a natural athlete, a high school football star in the Philadelphia suburbs. Coaches praise his strength and durability. He takes hit after hit on the field and always gets back up. He meets a young woman named Audrey, a gentle and principled physical therapy student who spends her days tending to people's injuries. She tells him she hates football because it is built on hurting other people, and that hatred matters to him.

One night, years before the film's present, David is in a car with Audrey. They are young, on the cusp of adult life. An accident happens--metal screams, glass shatters, their car crumples on a dark roadside. Later, he will tell Audrey and everyone else that he was badly hurt, that the crash ended his football career forever. It will become the cornerstone story of his life: the day he broke. But that story is a lie he will eventually have to confront.

By the time David Dunn is in his early forties, around the year 2000, he looks like an ordinary, tired man. He works as a security guard at a large football stadium in Philadelphia, a place of roaring crowds and concrete corridors. The job is unglamorous but fits him--a quiet protector, scanning faces as thousands of fans pour through the turnstiles. He wears a green security poncho when it rains, a simple waterproof garment that covers his clothes and hangs like a hooded cape when the wind lifts it.

At home, things are fraying. His marriage to Audrey Dunn is close to collapse. They sleep in separate beds in the same room, an arrangement that feels like an invisible wall between them. Their son, Joseph Dunn, is a soft-faced twelve-year-old who looks at his father with a kind of desperate admiration, wanting someone to believe in. David, though, feels hollow, ready to walk away from his life but too numb to fully admit it.

On a gray morning, David boards a passenger train in New York, heading back to Philadelphia after a job interview that might let him move away and start over. The train glides smoothly along the tracks, gentle vibrations running through the floor. He sits alone, stares out the window at the blur of industrial outskirts and winter trees, and absently twists his wedding ring. When a young woman named Kelly sits in the empty seat beside him, he slides the ring off and slips it into his pocket.

Kelly makes polite small talk. She asks if he is traveling home, if he has family. He is friendly but emotionally detached, giving half-answers, joking evasively when she notices there is no indentation on his finger where the ring was. The train feels like a liminal space, suspended between one life and another. Then, without warning, the world shudders.

The car lurches violently. Metal shrieks against metal. Coffee cups leap from tables and shatter. Kelly's eyes widen in panic; the overhead luggage slams around. In a roar of tearing steel, the train derails. Carriages jackknife and twist. Passengers scream, bodies flung against walls and ceilings, the world turning sideways and then upside down. The noise is monstrous, then abruptly nothing.

Silence returns in the aftermath. Emergency lights flicker over torn seats and twisted handrails. The air smells of dust, blood, scorched metal. Everywhere, there are broken bodies. Every other passenger--131 or 132 people, including Kelly--is dead, killed in an instant by impact and shrapnel. Only one man moves. David Dunn lies amid the wreckage, disoriented. He looks down at himself, expecting pain, wounds, something. His clothes are torn and dirty, but there are no cuts, no broken bones, not even a bruise. He stands up in the ruin of the train car, a solitary figure among the dead.

Later, in the chaotic triage area of a Philadelphia hospital, the fluorescent lights are just as harsh as the ones that once illuminated Elijah's birth. Doctors and nurses move frantically, blood on their gowns and hands. A physician sits beside David's bed, his face pale and incredulous. He tells David quietly that he is the sole survivor of the train crash. Out of all the passengers, he is the only one who lived. "You didn't even have a scratch," the doctor says, as if trying to convince himself he isn't misreading the charts.

The hospital corridors are crowded with grieving families. A memorial service follows, a somber gathering with flowers and candles, a list of names read aloud--more than a hundred dead in a disaster that has stunned the city. David stands apart, distant from both the mourners and the miracle everyone says he represents. He should be dead. Instead, he is untouched. The weight of that fact presses on him like a physical force.

When he leaves the memorial and walks through the parking lot toward his car, the sky is overcast, the air heavy with drizzle. On his windshield, under the wiper blade, he finds an envelope. It is not from the hospital or the authorities. He opens it and pulls out a simple card. In neat, formal handwriting, it asks a strange question: "How many days of your life have you been sick?" Below the question is an address: Limited Edition, a comic art gallery in Philadelphia.

The question lodges in his mind, unsettling in its specificity. How many days has he been sick? He cannot immediately recall. At home that night, in their modest suburban house, David moves through a domestic routine that feels paper-thin. He and Audrey exchange tense, cautious words in the kitchen, their separate beds in the bedroom glaring at each other like accusations. Joseph watches his father with worried eyes. The train crash has shaken him deeply, but it has also filled him with awe. His father walked away when everyone else died. Joseph wants there to be a reason for that.

David pockets the card. The next day or soon after, curiosity outweighs his reluctance. He drives to the address on the card and finds Limited Edition, a narrow, carefully curated comic art gallery on a Philadelphia street. Inside, the walls are lined with framed splash pages and original artwork, each piece spotlighted like a religious icon. Glass display cases hold rarities, the delicate surfaces reflecting the bright colors beneath. The entire space feels like a shrine to stories about extraordinary people.

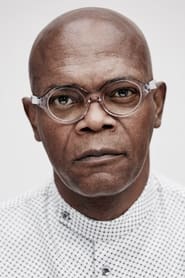

A man sits near the back, his posture upright but careful. He wears a dark suit and uses an elegant cane. His frame is thin, his movements stiff and economical. This is Elijah Price, grown from that fragile child into a man who has organized his life around his obsessions. He introduces himself as the owner of the gallery and the sender of the card. His eyes are intense, studying David as if he were a long-awaited painting finally delivered.

Elijah explains that he has a genetic disorder, osteogenesis imperfecta. "I've had thirty-seven breaks in my life," he says, or some similarly devastating number, recounting the fractures that have shaped him. He describes how he spent his childhood indoors, in hospitals, and with comic books--how his mother told him these stories were not just simple fantasies but distorted accounts of real people. Over time, he came to see the world through that lens. "If there is someone like me," he says, "someone who breaks like glass, then there has to be someone who doesn't break at all."

He looks directly at David. The intensity in his voice rises, a mixture of hope and obsession. He lays out his theory: somewhere out there are people who are "unbreakable"--men and women with remarkable endurance, almost supernatural resistance to injury, predisposed to dangerous situations. When David survived the train crash without a scratch, Elijah believed he had finally found one.

David reacts with disbelief and irritation. He insists he is just a man who got lucky. Elijah asks him pointedly about the card's question: how many days in his life has he been sick? David struggles to answer. He cannot remember missing work for illness. He cannot remember being bedridden as a child. The absence itself becomes suspicious, but he pushes the idea away. He leaves the gallery unsettled, dismissing Elijah as a fanatic even as the questions gnaw at him.

Back home, those questions invade his quiet moments. Joseph becomes involved; father and son sit at the kitchen table trying to remember a time when David had the flu, a fever, anything. Joseph cannot think of a single day. The realization makes Joseph's eyes light up. He begins to look at his father as if a comic-book hero has stepped into their living room. David protests, clinging to rational explanations, but Joseph's faith begins to grow.

At the stadium, where the crowds filter through metal detectors, David's work takes on a new weight. He stands at his post in his green rain poncho when it drizzles, watching the river of people. He has always been good at his job, possessing a kind of sixth sense about trouble. Elijah suggests there is nothing ordinary about that. When David brushes against a man in a military-style coat, something unusual happens. A brief rush of images flashes through his mind, like a dream compressed into a heartbeat. He sees a particular handgun, a shape and color that lodges in his mind. The contact leaves him shaken.

Later, he meets Elijah again and tells him about it--about the image of the gun that appeared when he bumped the stranger. Elijah's eyes sharpen. "You have a gift," he insists. He argues that David has an extrasensory perception of people's misdeeds, that his "intuition" at work is actually a superhuman ability that helps him sense danger.

David resists, but Elijah is relentless. When David describes the gun in detail, Elijah decides to test this new data. He follows the man, trailing him down into a stairwell in a public building. The staircase is long and steep, wrapping around a concrete shaft. Elijah grips the handrail with his weak hand, his cane tapping each step. He is so focused on the man ahead of him that he misjudges a placement. His foot slips.

He falls.

The world becomes a blur of concrete, railings, and pain. His body bounces and twists down the stairwell, bones fracturing with wet cracks. The sound of his bones breaking is sickening, each impact adding to the internal damage. When he finally comes to rest at the bottom, gasping, his limbs are twisted. In front of him, just before he blacks out, he sees the man's bag spilled open and the exact handgun from David's vision glinting on the floor. The gun is real. David's vision was real. Elijah's face, twisted with pain, also shines with grim satisfaction. His theory is one step closer to proof.

He wakes in a rehabilitation facility later, encased in casts, his body even more fragile than before. The fall has left him wheelchair-bound. Nurses tend to him. He stares at the ceiling, painkillers dulling but not erasing the ache in every bone. Still, he feels vindicated. Each injury is another step in his quest. If he breaks enough, maybe he will finally find the man who does not break.

Meanwhile, David's family life continues to strain. Audrey believes they might be able to salvage something between them, while David seems ready to give up. Joseph hovers between them, sensing more than he can articulate. When he hears Elijah's theories, they resonate with his childlike longing for a hero. If his father is unbreakable, maybe their family can be, too.

Elijah leans into Joseph's hopes. He reminds the boy of the train crash, of his father's lack of injuries, of his career as a football player who never seemed to get hurt. He plants the idea that the stories in comic books--origin stories, hidden identities--might be happening in their own home. Joseph becomes convinced his father is a superhero. David's continued denials only frustrate him.

Elijah challenges David more directly. He asks about the supposed injury that ended David's football career. David insists he was seriously hurt in that car accident in college, badly enough to stop playing forever. Elijah asks if he remembers the hospital records, the surgeries, the scars. The more Elijah pushes, the more the memory begins to shift in David's mind, details blurring at the edges. There are flashes of the crash, of the car crushed around him, of twisted metal. He remembers ripping a car door off its hinges to pull Audrey free. He does not remember pain.

To test his physical limits, David finally agrees to a simple experiment at home. In the dim light of their basement/garage, among old boxes and dusty football trophies, he lies on a bench and grips a barbell. Joseph stands nearby, solemn and excited. David lifts the weights, expecting strain, but finds he can push much more than he thought. Joseph adds more weight--improvised loads made of paint cans and household objects until the bar is loaded with around 350 pounds or more. Each time, David braces and lifts, his muscles working but never failing. With every repetition, Joseph's eyes widen. "You did it," he whispers. "You're strong."

The bar trembles in David's hands, but he feels something beyond physical exertion: a dawning awareness that he is not normal. The realization both thrills and terrifies him. If he has been hiding from his own nature all these years, what does that say about his life? About his marriage? About the choices he made?

As this internal tension grows, Joseph's belief in his father's invulnerability curdles into desperation. One evening, in their kitchen, the air thick with unspoken conflict, Joseph makes a terrible decision. He has heard Elijah's arguments, seen the weightlifting. He wants proof that cannot be denied. He takes David's revolver from wherever it is kept in the house and loads it, his small hands clumsy but determined.

He steps into the kitchen where David and Audrey are talking and raises the gun, pointing it directly at his father's chest. Audrey gasps, frozen. David stares at his son in shock. Joseph's voice shakes as he explains his reasoning: if David is unbreakable, the bullet will not hurt him. They will all know the truth. His faith in his father is absolute, but it has become dangerous.

The room fills with raw emotion. Audrey pleads with Joseph, tears in her eyes, telling him to put the gun down. David speaks calmly but firmly, telling his son that he is not what Elijah says he is, that a bullet will kill him like anyone else. Joseph insists he is lying, that he is hiding his true identity. The standoff stretches, the barrel of the gun unwavering. David has to reach his son on a deeper level. He tells Joseph that if he pulls the trigger, he will leave his mother alone, he will go to prison, their family will be destroyed, regardless of whether the bullet hurts him or not. That truth finally pierces the boy's fervor. Joseph breaks down, sobbing, and slowly lowers the gun. The tension drains from the room in a rush of relief and exhaustion. The incident leaves a scar on all three of them, an emotional fracture that mirrors the physical breaks in Elijah's life.

David cannot ignore the pattern any longer. He thinks back through his history. He remembers childhood, when he was pushed into a swimming pool and sank, thrashing in panic. He nearly drowned before someone pulled him out. The experience left him with a deep fear of water. Over the years, he avoided swimming, avoided rain when he could. He begins to suspect that water is not just a phobia but a true weakness, the one thing that can overwhelm him. For the first time, his life begins to resemble a comic-book origin story, complete with a "kryptonite."

At Elijah's urging, David agrees to a more direct exploration of his strange intuition. One night, he goes to 30th Street Station in Philadelphia, a busy train station with a constant flow of commuters. The cavernous hall echoes with voices and footsteps. David stands in the center of the moving crowd wearing his green poncho, hood up, making him an anonymous figure among many.

He spreads his arms slightly, allowing people to brush against him as they pass. Each contact sends a jolt of images into his mind--brief visions, like disjointed scenes from grim home movies. A man he touches is a jewel thief, shown shattering a jewelry store display and stuffing handfuls of glittering stones into his pockets. Another is a sexual predator, glimpsed in a dark alley with a terrified victim. David recoils slightly with each vision, feeling the weight of their sins pressing into him.

Then a larger man in work clothes, carrying a janitor's key ring and tools, bumps into him. The contact is electric. A horrific sequence burns itself into David's mind. He sees the man breaking into a suburban home, a father struggling against him and being overpowered. He sees the father beaten and killed. He sees the janitor tie up a mother and three children, dragging them through their own house, chaining them in a basement. He feels the sadism and entitlement in the man's movements. The vision is longer, deeper, saturated with dread.

When it ends, David's breathing is ragged. Out of all the sins he just witnessed, this one feels immediate, ongoing. Somewhere in the city, right now, that family is in mortal danger. Elijah has told him that if he is what Elijah believes he is, he has a responsibility to act. In that moment, David chooses. He will not walk away.

He follows the janitor at a distance as the man leaves the station, watching the curve of his shoulders, the jangling of his keys. The man drives to a two-story suburban home. It is the kind of house that might have a trimmed lawn and toys in the yard, the sort of place where ordinary families feel safe. The sky is dark, the streets quiet. David's poncho hangs around him like a shadow as he approaches.

He slips into the house, moving carefully. Inside, the lights are low. The air is heavy with the sense that something is wrong. Furniture is displaced, a table overturned. There is a smear of something dark on a wall. He hears muffled sounds, chains clinking faintly. He moves through the rooms with increasing urgency.

Downstairs, in a basement or utility area, he finds part of what he saw in his vision: two daughters chained to pipes, frightened and exhausted. (Different tellings vary whether there are two or three children; here, two teenage daughters are clearly present.) He speaks softly, trying to reassure them, promising he will get them out. He begins to free them from their restraints. Then he moves through the house and finds the mother, bound to a radiator or bed, slumped and still. He checks for signs of life, but she is dead. The janitor has already killed her. In this house, two parents are dead: the father beaten and murdered earlier, off-screen before David arrived; the mother bound and slain, her death a silent accusation. Both deaths belong to the janitor's cruelty, and David is too late to save them.

Before he can process this, the janitor attacks. The man barrels into him from the side, enraged at the intrusion. They crash against a wall and then stagger toward a staircase. The janitor grabs David and hurls him over the upstairs railing. For a split second, David is weightless. Then he plunges down into darkness and into his greatest fear.

He lands not on solid ground but on the plastic-covered surface of a backyard swimming pool, its winter cover stretched tightly across like a false floor. The force of his impact tears the cover from its moorings. It collapses beneath him, and he falls into the cold water. The heavy poncho drags him down. The sheet of plastic wraps around him, clinging like a shroud. He flails, disoriented, unable to find the surface.

Under the water, everything is muffled and blurred. He cannot swim; water has always been his enemy. His lung capacity, his strength, the invulnerability that has carried him through car wrecks and train disasters--all of it means nothing here. He is drowning. Panic surges through him as he thrashes against the slick plastic, his fingers searching for any break in the cover.

On the pool deck, the two daughters, still partially bound but able to move, see him struggling beneath the sagging cover. Their eyes widen. Despite their fear, despite their chains, they act. They find a long pole--part of the pool equipment--and push it out over the water, toward the dark shape trapped below. David, nearly out of air, gropes in the water and his hand closes around the pole. The girls pull with all their strength, dragging the plastic and his weight toward the edge. Finally, his head breaks the surface. He gasps in lungfuls of air, sputtering, clinging to the pole as they haul him onto the deck. The daughters, still chained, have just saved the life of the man who came to save them.

Soaked and shaken, David lies there for a moment, rain dripping from the poncho, water pooling around him. He has come face-to-face with his weakness and survived only through the courage of the very people he was trying to rescue. The lesson is etched into him as deeply as any scar: he is unbreakable until he meets water.

He staggers back into the house, determined to finish what he started. He finds the janitor upstairs, moving around the victims' home with grotesque familiarity. Silently, David moves behind him, wraps his powerful arms around the man's neck, and holds on. The janitor struggles, slamming David against walls, but David doesn't let go. He uses his weight and strength, tightening the choke. The man claws at him, kicks against the floorboards, lurches backward, but David is relentless. Eventually there is a sickening crack--either the janitor's neck breaking or his windpipe collapsing--and the body goes limp. In that moment, David Dunn, the man who survived the train crash, kills the janitor with his bare hands. It is an act of brutal necessity, vigilante justice born from his acceptance of who he is.

When it is over, the house is quiet except for the soft sobbing of the daughters. Somewhere in the house lies the father, already dead at the janitor's hands. The mother's body remains where David found it. Two parents are gone; two children are alive because of him. He frees the girls completely and leads them toward safety. Later, the police arrive and find the dead janitor, the dead parents, and the rescued children. They piece together a partial story: an unknown man in a hooded green raincoat intervened and saved the daughters, killing the invader. The identity of this hero is unknown, but the image is seared into their minds.

That night, David returns home, exhausted and changed in a way that shows in every line of his body. He enters the bedroom where he and Audrey sleep in their separate beds. The distance between those beds is no longer tolerable. He sits with her and, haltingly, begins to talk. He admits that something has been happening to him, that he has been denying a part of himself for years. He does not need to describe every detail for her to see that something profound has shifted. They lean toward each other, emotionally reconnecting after so much estrangement. There is no grand speech, just the quiet intimacy of two people choosing to start again. She suggests they try to rebuild their relationship, to heal what has been broken. David agrees. What he did that night--risking his life to save strangers--has reminded him of who he once wanted to be, for himself and for her.

The next morning, the house is filled with the ordinary sounds of breakfast: chairs scraping, cereal being poured, a newspaper crackling. Joseph sits at the table, still carrying the emotional weight of the gun incident, still wrestling with fear and hope. David sits across from him, the morning light soft on his face. He holds the newspaper, reading the front page article about the previous night's events.

The headline speaks of an anonymous hero who rescued two girls from a home invader and killed the perpetrator. Beneath the headline is a police sketch, drawn from the girls' accounts: a tall man in a hooded green poncho, his face shadowed. David's costume. His secret.

Without a word, he folds the paper so that the article and sketch face up and slides it across the table to Joseph. The boy looks down, reads the headline, sees the drawing. His eyes lift slowly to his father's face. David meets his gaze and nods, just once. The confirmation hits Joseph like a wave. His eyes fill with tears. The faith he clung to, the belief that nearly drove him to shoot his own father, is finally validated. He promises silently, in the way he looks at David, to keep the secret. More than that, he sees his father not as a distant, failing adult but as something extraordinary and deeply human at once.

A little later, David goes back to Limited Edition. The gallery's quiet, curated atmosphere feels different now that he has acted on the possibilities Elijah presented. As he enters, he meets Elijah's mother again, older now but still dignified, still speaking of comic books with the reverence of someone discussing great literature. She explains to David the archetypes of villains: some use brute strength, others use their minds. The ones who fight with their intellect are often the most dangerous. Her words hang in the air, foreshadowing the truth that is about to spill into the open.

David moves to the back of the gallery, to Elijah's private office/studio. The room is cluttered with research: newspaper clippings about disasters pinned to boards, files arranged in obsessive patterns, diagrams and notes detailing catastrophic accidents. Hotel fires. Airplane crashes. Train derailments. They are the secret history of Elijah's life, though David does not yet see it.

Elijah sits in his wheelchair, his legs immobilized in braces, his posture stiff but his eyes gleaming. He speaks as if a long journey is reaching its destination. He tells David they now know his powers--his strength, his invulnerability, his ability to sense wrongdoers through touch. He talks about the hero's calling, about how David's survival of the train crash was not chance but destiny. He speaks of purpose with the fervor of a man finally assured of his place in the world.

Then he extends his hand.

The gesture seems simple, a handshake between two men who have shared secrets. But for David, touch is more than physical. He hesitates, knowing that any contact could show him more than words ever could. Yet he needs to know. Slowly, he reaches out and takes Elijah's hand.

The vision hits him like an explosion.

In a rapid, unbroken sequence, David sees Elijah's life from a hidden angle. He sees a crowded hotel corridor, guests moving about unaware. He sees Elijah, using his cane and careful steps, tampering with something, leaving a device or altering a system. Later, flames ravage the building, smoke pouring from windows. People scream as they are trapped and die. That fire was not an accident--it was a deliberate act. Elijah caused it.

The images shift. An airplane on a runway, glinting in the sun. Elijah in a hangar or control area, hands working with the same meticulous focus he brings to his art. Something vital is sabotaged. Later, the plane plummets from the sky, breaking apart, scattering wreckage and bodies over a wide area. Another mass-casualty "accident" that was in fact an act of terrorism. Again, Elijah is the architect.

Then David sees the train he was on, before it left New York. He sees Elijah moving among the cars and mechanisms, his face impassive, his movements precise. He sees the moment something is altered deep within the machinery, the seed of catastrophe planted. He realizes that the train derailment that killed all the other passengers--Kelly, the 131 or 132 souls who never made it home--was orchestrated. Elijah engineered the train crash. Elijah is not just a man with a theory. He is the killer who set all these tragedies in motion.

The vision ends. David staggers back, releasing Elijah's hand as if burned. His face drains of color. The man he thought was his guide, even his friend, is revealed as a mass murderer. Elijah watches his reaction closely. He is not ashamed; he is almost radiant with revelation.

He speaks in a quiet, tremulous voice that carries years of pain and yearning. "Do you know what the scariest thing is?" he asks. "To not know your place in this world." Now, he says, that fear is gone. "Now that we know who you are, I know who I am." He explains that his whole life he thought he might be a mistake, a misalignment of nature--a man so weak and brittle that existence itself seemed to reject him. But if David is the hero, if he is the unbreakable man, then Elijah, by necessity, must be his opposite. The villain. The mastermind. He mentions that the kids used to call him "Mr. Glass" because of his condition. The name was meant to mock him, but now he embraces it as a title. Mr. Glass, the comic-book villain brought to life.

He justifies the atrocities in a chilling moral calculus. The hotel fire, the plane crash, the train derailment--hundreds of lives sacrificed--were, in his mind, necessary experiments to find the one unbreakable person. He says that every hero story has a beginning marked by tragedy, and that his own suffering, his broken bones, led him inevitably to this role. In his twisted logic, the deaths are acceptable collateral damage for the discovery of a real-life superhero. He believes that by creating David's opposite, he has given his own existence meaning.

David listens, horror growing in him like a wave. The gravity of what Elijah has done crashes down: all those memorial services, all those families destroyed, all so Elijah could test a theory, could force the universe to produce a counterpart for him. There is no physical fight in the office, no dramatic brawl that sends them crashing through glass cases. The confrontation is entirely moral, the violence contained in what Elijah has already done.

David says nothing at first. The betrayal cuts too deeply. The man who pushed him to embrace his strength has revealed himself as the architect of his greatest trauma and the murderer of hundreds. David's face is a mask of grief and disgust. He steps back from Elijah, from the gallery, from the world that Elijah tried to frame in comic-book terms. He leaves the office, walks out past the framed art and glass cases, and into the daylight.

In the aftermath, he does the thing that confirms his role not only as a man of strength but as a man with a conscience. He goes to the authorities.

Later, Elijah Price is led away in handcuffs, his wheelchair pushed by officers down sterile, echoing hallways. The headlines tell a new story now, one that recontextualizes the disasters that have haunted the city for years. Investigations uncover the pattern of orchestrated tragedy. On-screen text would say it plainly: David Dunn turned Elijah Price in to the police. Elijah was tried and convicted on multiple counts of murder and terrorism. He is confined to a psychiatric hospital for the criminally insane, where his brilliant mind and broken body will remain under lock and key.

No main character dies in this story: David Dunn lives, having finally accepted his unusual nature. Audrey Dunn lives, her marriage tentatively mending as she realizes the man she loves has depths she never imagined. Joseph Dunn lives, entrusted with the secret of his father's heroism and learning that legends can be both inspiring and painfully human. Elijah Price--Mr. Glass--lives, but his life is now defined by the revelation of his crimes and his role as a villain, the opposite number he always believed must exist.

The deaths, however, are many and heavy. Every passenger on that train except David--the 131 or 132 people whose lives ended in twisted steel--died because of Elijah. The victims of the hotel fire and the airplane crash died because of Elijah. In that suburban house, the father died off-screen at the hands of the sadistic janitor, his murder a grim fact that gives weight to David's vision. The mother died bound and helpless, her life taken by the same intruder before David could reach her. The janitor himself died when David strangled him, his neck snapped or crushed as David used his strength to stop further harm.

In the end, the symmetry Elijah believed in is real but terrible. There is a man who breaks like glass and a man who does not break at all. One uses his mind to create disasters, to test the limits of fate. The other uses his body and strange senses to protect, to save who he can, even when he cannot save everyone. Their confrontation does not end in a climactic battle of fists but in a quiet, devastating recognition and a simple, heroic choice: to turn a monster in, even when that monster is the one who gave your life its strangest meaning.

The story closes with David's life continuing under the surface of normalcy, a man who goes to work, who sits at his kitchen table, who loves his wife and son, and who sometimes steps into the night wearing a green poncho that hides his face. Somewhere behind locked doors, Elijah sits in a psychiatric ward, no longer questioning his place in the world. He is Mr. Glass, villain to an unbreakable man. Their destinies are entwined, forever opposite ends of a spectrum that began the day a baby was born with broken bones in a department store fitting room and eventually met the day a train left its tracks and one man walked away without a scratch.

What is the ending?

In the ending of "Unbreakable," David Dunn confronts Elijah Price, who reveals himself as the mastermind behind a series of disasters, including the train crash that left David as the sole survivor. Elijah, who has been manipulating events to find someone like David, admits to being the villain. David ultimately decides to stop Elijah, leading to his arrest. The film concludes with David accepting his identity as a hero, while Elijah is imprisoned, content with his role as a villain.

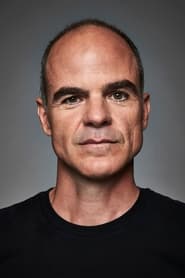

As the film approaches its climax, the tension builds in a series of pivotal scenes. David Dunn, played by Bruce Willis, has been grappling with the revelation of his extraordinary abilities and the implications of his survival from the train crash. He is now more aware of his strength and resilience, but he is still conflicted about his identity and purpose.

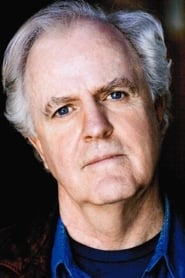

In a dimly lit room, David meets with Elijah Price, portrayed by Samuel L. Jackson, who has been a guiding figure throughout the film. Elijah, who has a rare condition that makes his bones extremely fragile, has been waiting for this moment. He reveals his true nature as the orchestrator of the train crash, explaining how he has been searching for someone like David, someone who embodies the opposite of his own fragility. Elijah's eyes gleam with a mix of excitement and madness as he lays out his philosophy: that for every hero, there must be a villain.

David, feeling a mix of anger and betrayal, listens intently as Elijah recounts the events that led to the crash. Elijah's voice is calm yet filled with a manic energy, as he describes how he has pushed the boundaries of fate to find David. The emotional weight of the moment hangs heavy in the air, as David grapples with the reality that he has been a pawn in Elijah's grand design.

As the confrontation escalates, David's internal struggle becomes evident. He is torn between the desire to understand his own powers and the moral implications of Elijah's actions. The scene is charged with tension, as David realizes that Elijah's actions have resulted in countless deaths, all in the name of finding him. The camera captures the intensity of their exchange, focusing on the contrasting physicality of the two men: David's imposing strength against Elijah's frail form.

In a decisive moment, David makes the choice to stop Elijah. He understands that he must embrace his role as a protector, not just for himself but for others. The scene shifts to a police station, where David reveals Elijah's confession to the authorities. The weight of his decision is palpable; he is no longer just a passive survivor but an active participant in the fight against evil.

Elijah, now in custody, sits in a stark interrogation room, a satisfied smile creeping across his face. He has achieved his goal of finding David, and despite his imprisonment, he feels a sense of fulfillment. The camera lingers on his face, capturing the complex emotions of a man who has dedicated his life to the pursuit of understanding his own existence through the lens of comic book mythology.

The film concludes with David embracing his identity as a hero. He walks away from the police station, a sense of purpose radiating from him. The final scenes show him using his abilities to help others, solidifying his role as a protector. Meanwhile, Elijah, confined to a prison cell, reflects on his actions, content in the knowledge that he has played his part in the larger narrative of good versus evil.

In the end, David Dunn stands as a symbol of resilience and strength, while Elijah Price embodies the complexity of villainy and the lengths one might go to in search of meaning. Their fates are intertwined, each representing a side of the same coin, forever changed by their encounter.

Is there a post-credit scene?

In the movie "Unbreakable," there is no post-credit scene. The film concludes with a final scene that wraps up the story without any additional content after the credits. The last moments focus on David Dunn's realization of his abilities and his confrontation with Elijah Price, also known as Mr. Glass. The film ends on a note that emphasizes the themes of identity and the nature of heroism, leaving the audience with a sense of closure regarding the characters' arcs.

What is the significance of David Dunn's ability to sense the emotions of others?

David Dunn, played by Bruce Willis, discovers that he has the ability to sense the emotions and intentions of others when he touches them. This ability serves as a crucial plot element, as it not only highlights his unique powers but also deepens his internal conflict about his identity and purpose. It becomes a tool for him to understand the world around him and ultimately leads him to confront his destiny as a hero.

How does Elijah Price's character influence David Dunn's journey?

Elijah Price, portrayed by Samuel L. Jackson, is a pivotal character who influences David Dunn's journey significantly. As the comic book enthusiast who believes in the existence of superheroes and supervillains, Elijah acts as a mentor and antagonist. His obsession with finding someone like David, whom he sees as a 'hero,' drives the narrative forward. Elijah's manipulation and eventual revelation as the villain force David to confront his own abilities and responsibilities.

What role does the train crash play in the story?

The train crash at the beginning of the film serves as a catalyst for the entire narrative. It is the event that leads to David Dunn's awakening to his extraordinary abilities, as he is the sole survivor of the crash. This incident not only sets the stage for his exploration of his powers but also symbolizes the fragility of life and the emergence of a hero from tragedy. The crash is a turning point that propels David into a journey of self-discovery.

How does David Dunn's relationship with his son affect his character development?

David Dunn's relationship with his son, Joseph, is central to his character development. Joseph, played by Spencer Treat Clark, idolizes his father and encourages him to embrace his abilities. This father-son dynamic adds emotional depth to David's journey, as he grapples with his fears and insecurities. Joseph's unwavering belief in David's potential pushes him to confront his identity and ultimately accept his role as a protector.

What is the significance of the color green in the film?

The color green is a recurring motif throughout 'Unbreakable' that signifies David Dunn's journey and transformation. It is often associated with his character, appearing in his clothing and the lighting during key scenes. Green symbolizes growth, renewal, and the emergence of his true self as a hero. The color contrasts with Elijah Price's use of purple, representing his villainous nature, and highlights the duality between the two characters.

Is this family friendly?

"Unbreakable," produced in 2000, is a film that delves into themes of identity, trauma, and the nature of good versus evil. While it is not overtly graphic, there are several elements that may be considered objectionable or upsetting for children or sensitive viewers:

-

Violence and Death: The film includes scenes that depict violence and the aftermath of violent acts, including a train crash that results in numerous fatalities. The emotional weight of these scenes may be distressing.

-

Themes of Isolation and Loneliness: The protagonist, David Dunn, experiences feelings of isolation and struggles with his identity, which may resonate deeply with sensitive viewers.

-

Mental Health Issues: The character of Elijah Price, who has a rare condition that makes his bones extremely fragile, deals with significant emotional and psychological challenges. His backstory includes themes of trauma and suffering.

-

Paranoia and Fear: There are moments of suspense and tension that may evoke feelings of fear or anxiety, particularly as David uncovers his abilities and the implications of his existence.

-

Mature Themes: The film explores complex themes such as destiny, morality, and the nature of heroism, which may be difficult for younger audiences to fully grasp.

Overall, while "Unbreakable" is not excessively graphic, its mature themes and emotional depth may not be suitable for all children or sensitive viewers.