Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

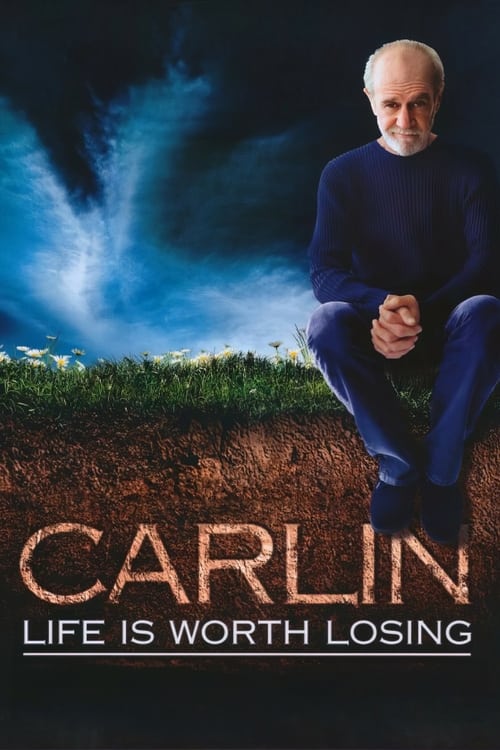

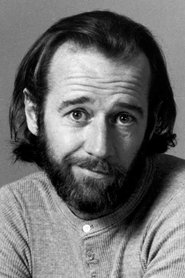

George Carlin strides onto the dimly lit stage of the Beacon Theatre in New York City, the air thick with anticipation from the packed audience on this fateful night in 2005. Towering tombstones loom behind him like silent sentinels of doom, their gray stone etched with mocking epitaphs that foreshadow the grim themes to come--genocide, depression, apocalypse. The spotlight catches his lean frame, dressed in a simple black shirt and jeans, his eyes sharp and defiant after 341 days of sobriety from drugs, a milestone he proudly declares right at the outset. "I'm 341 days sober," he announces with a wry grin, his voice cutting through the hush like a blade, "and 2006 will be my 50th year in show business." The crowd erupts in applause, but Carlin wastes no time on sentiment; tension simmers as he launches into his opening salvo, "A Modern Man," mocking humanity's puffed-up evolution. He paces the stage with predatory energy, gesturing wildly: "You think you're a modern man? With your cell phone and your SUV? You're just a goddamn ape with a better haircut!" Laughter ripples, but beneath it, a dark undercurrent builds--life's pretensions are fragile, and Carlin is here to shatter them.

Smoothly transitioning, Carlin leans into the microphone, his tone shifting to sardonic whimsy for "Three Little Words." He dissects death's euphemisms with surgical precision, building momentum as the audience leans forward, caught in his verbal web. "Passed away? Departed? No--dead! Dead as a doornail!" he barks, mimicking simpering mourners. The tombstones seem to grow more ominous in the shifting lights, casting long shadows that symbolize the mortality he's toying with. No other characters emerge; it's Carlin alone against the world, his words the only weapons, his audience unwitting accomplices in this descent into darkness. Emotional weight presses in as he reveals the fragility of language hiding horror--torture, suicide, extinction--all lurking just beyond polite phrases.

Tension escalates as Carlin dives into "The Suicide Guy," his voice dropping to a conspiratorial hush that draws the crowd deeper into the abyss. He paints vivid, hypothetical vignettes of a desperate everyman teetering on the ledge, the wind whipping his coat on a high-rise rooftop. "He's up there, thinking, 'One step... and it's over,'" Carlin intones, pausing for the laughter that masks unease. But he twists the knife: the guy jumps, only to bounce off an awning, splatter on a parked car, then stagger bloodied to his feet, mumbling, "Fuck it, I'll try again tomorrow." No real death occurs--no bodies hit the floor, no perpetrators wield knives--but Carlin catalogs suicidal folly with relentless detail: pills that fail, guns that jam, ropes that snap. The audience squirms, laughter turning nervous as he builds to the emotional peak, eyes gleaming with dark glee. "Life is worth losing!" he crows, echoing the special's title, the tombstones now pulsing like heartbeats in the spotlights.

Carlin doesn't relent; he pivots seamlessly into "Extreme Human Behavior," stretching the routine to a grueling 13 minutes that ratchets the momentum toward societal collapse. His gestures grow broader, sweat beading on his brow under the hot lights--unbeknownst to the crowd, heart failure gnaws at him even now, a secret revelation that will surface later in his life. He eviscerates torture and genocide, describing waterboarding with chilling specificity: "They pour it on, you drown awake, gasping like a fish on the deck." No named victims fall, no heroes intervene, but the confrontations are ideological--Carlin versus humanity's savagery. He confronts the audience directly: "You love it! Deep down, you do!" Tension coils tighter, the Beacon's ornate ceiling seeming to close in as he lists mass killings, from historical slaughters to hypothetical nukes, each punchline a revelation of our bloodlust. Emotional rawness peaks when he admits the thrill in destruction, his face contorting in mock ecstasy, leaving viewers viscerally unsettled.

The pace quickens with "The All-Suicide TV Channel," a 3-minute frenzy of absurdity that propels the narrative forward like a runaway train. Carlin envisions a reality network broadcasting live self-destruction: "Ratings gold! 'Jumping with the Stars'! 'Survivor: Gas Oven Edition'!" He mimes contestants overdosing on camera, their final twitches close-up for prime time. Laughter booms, but the vivid imagery--foam at the mouth, eyes bulging--builds horrific momentum. No actual suicides unfold on stage, yet Carlin personifies them as desperate souls chasing fame in death, confronting their own worthlessness. The tombstones watch impassively, visual anchors amplifying the chaos, as he climaxes with a producer's pitch: "Twenty-four-hour suicide--it's gonna be huge!" The crowd's cheers feel like complicity, tension humming like a live wire.

Now fully immersed in disdain, Carlin unleashes "Dumb Americans," a 10-minute tour de force that explodes with fury, targeting the heartland's oblivious masses. Picture Joe Sixpack, the archetypal clueless husband, beer belly protruding like a tumor, standing beside his wife at a protest--her sign reads "God Hates Your Lies," while he balances nachos, pie, and a beer, hands perpetually stuffed. "Nachos in one, pie in the other, beer to wash it down!" Carlin roars, mimicking the shove into gaping mouths. Visual hilarity meets emotional indictment: these fat, gun-toting patriots, assault rifles strapped to backs because "hands must remain free at all times to hold food!" He confronts America's elite next, his voice rising to a thunderous crescendo: "It's a big club--and you ain't in it!" The revelation hits like a gut punch--they own the corporations, the Senate, Congress, state houses, city halls, judges in their pockets. "They'll get it all from you sooner or later 'cause they own this place!" No physical brawl erupts, but this verbal showdown lays bare the pyramid of power, tension peaking as Carlin's face reddens, the audience hanging on every word, the tombstones a graveyard for the American dream.

Undeterred, he segues into "Pyramid of the Hopeless," an 8-minute dissection of despair's hierarchy, building inexorably toward total breakdown. Carlin sketches an invisible pyramid: at the base, the hopeless masses; above, the addicted, the violent, the powerful--all doomed. He confronts the elites again, their "criminal friends on Wall Street" siphoning wealth, leaving scraps. Emotional depth surges as he humanizes the bottom rung--Joe Sixpack variants, drowning in stupidity--yet offers no mercy. "You're all fucked!" he declares, pacing furiously, the stage lights flickering like impending doom. Revelations cascade: society's layers are rigged, confrontation inevitable, outcome predestined extinction. The audience feels the momentum, laughter edged with dread.

Carlin's intensity surges in "Autoerotic Asphyxia," a 4-minute plunge into solitary perversion, tension twisting into the grotesque. He describes lone men in nooses, plastic bags over heads, cocks in hands--strangulation for orgasm. "One good tug, and boom--lights out mid-come!" No victims named, no killers, but the self-inflicted deaths pile up hypothetically: widows finding husbands dangling, neighbors sniffing the aftermath. Vivid visuals assault the mind--bulging eyes, purple faces--Carlin's mimicry so precise it evokes revulsion and mirth. Emotional pivot: this is peak human stupidity, a private confrontation with mortality, climaxing in futile ecstasy.

Shifting gears with macabre whimsy, "Posthumous Female Transplants" (3:34) imagines dead women's organs in living men: "Heart from a suicide chick--now you feel her pain!" No surgeries occur, but the routine confronts bodily violation, revelations of recycled despair. Tension simmers as Carlin quips on yeast infections next ("Yeast Infection," 4:38), turning vaginal horror into cosmic joke: "It's alive! Eating you from inside!" Fungal wars rage unseen, building absurd momentum toward planetary scale.

The special hurtles toward its feverish core with "Excess: Fires and Floods," Carlin reveling in Earth's vengeance. Massive blazes and deluges wipe humanity clean, the planet's "glorious rebirth" via our annihilation. "Fires! Floods! Good riddance!" he exults, arms wide, tombstones glowing like victorious monuments. No specific dates or times mark these cataclysms, but the emotional high soars--relief in extinction, tension resolving into cathartic release.

Climax erupts in the finale, "Coast-to-Coast Emergency" (6:50), a reworked remnant from Carlin's aborted 2001 special "I Kinda Like It When a Lotta People Die"--post-9/11 scars repurposed into chaos. America fractures: disasters cascade from sea to shining sea. "Uncle Dave's" spirit haunts it--floods in California, quakes in the Midwest, twisters in the East, all simultaneous. Carlin mimes panicked calls: "911? The dam broke! No, wait--earthquake! Tornado!" No characters perish onstage, but mass death unfolds verbally: millions drown, burn, crush. Confrontations peak--government vs. nature, elites vs. masses--with Carlin as gleeful narrator. "It's beautiful! The whole country's goin' down!" Tension shatters in apocalyptic glee, momentum crashing like waves on the tombstones.

As the laughs subside, Carlin stands spent, sweat-soaked, heart straining unseen--he'll be hospitalized for failure soon after, a posthumous revelation of his own fragility. The audience rises in thunderous ovation at the Beacon Theatre. He bows, exits stage left into shadows, lights dimming on the tombstones--final, unyielding symbols of a world worth losing. Directed by Rocco Urbisci, this 75-minute HBO descent ends not with resolution, but raw truth: no heroes survive, no villains triumph, just humanity's laughable doom. Carlin lives on in memory, sober and savage to the end, the stage empty, applause echoing into silence.

More Movies Like This

Browse All Movies →What is the ending?

In the ending of "George Carlin: Life Is Worth Losing," George Carlin delivers a powerful closing segment that encapsulates his views on life, death, and the absurdities of modern existence. He reflects on the human condition, emphasizing the inevitability of death and the importance of embracing life despite its challenges. The performance concludes with Carlin's signature humor, leaving the audience with a mix of laughter and contemplation.

As the final act unfolds, the stage is set with Carlin standing confidently under the spotlight, the audience eagerly awaiting his insights. He begins by addressing the theme of mortality, a recurring motif throughout his performance. Carlin's tone is both serious and humorous, as he juxtaposes the gravity of life with his trademark wit. He shares anecdotes and observations about the absurdities of societal norms, the futility of certain human behaviors, and the inevitability of death that awaits everyone.

In this climactic moment, Carlin's internal motivation is clear: he seeks to provoke thought and reflection among his audience. He challenges them to confront their fears and embrace the reality of life, urging them to find meaning in the chaos. His emotional state oscillates between humor and poignancy, as he navigates the delicate balance of making people laugh while also encouraging them to think deeply about their existence.

As he wraps up his performance, Carlin's delivery becomes more impassioned. He emphasizes that life, despite its hardships, is worth living. The audience responds with laughter and applause, a testament to the connection he has forged with them throughout the show. The lights dim slightly, creating an intimate atmosphere as he concludes with a final, impactful statement that resonates with the audience.

The performance ends with Carlin taking a moment to soak in the applause, a satisfied smile on his face. He acknowledges the audience's appreciation, embodying the spirit of a performer who has shared not just jokes, but a piece of his philosophy on life. As he exits the stage, the audience is left with a lingering sense of reflection, contemplating the messages he has imparted.

In this way, the ending of "George Carlin: Life Is Worth Losing" encapsulates the essence of Carlin's comedic genius, leaving viewers with both laughter and a deeper understanding of the complexities of life. The fate of Carlin, as the central figure, is one of triumph in his ability to connect with the audience, leaving them inspired to embrace life in all its unpredictability.

Is there a post-credit scene?

"George Carlin: Life Is Worth Losing," produced in 2005, does not contain a post-credit scene. The special concludes with Carlin delivering his final thoughts and reflections on life, society, and the human condition, leaving the audience with a sense of contemplation rather than a follow-up scene. The absence of a post-credit moment aligns with Carlin's style, focusing on the weight of his message rather than additional comedic content after the main performance.

What are some of the key topics George Carlin discusses in his stand-up routine in the film?

In 'George Carlin: Life Is Worth Losing', Carlin tackles a variety of provocative topics including the absurdity of modern life, the state of the world, and the human condition. He delves into themes such as the futility of existence, the flaws in societal norms, and critiques of political correctness, all delivered with his signature wit and sharp observational humor.

How does George Carlin's performance style contribute to the film's impact?

Carlin's performance style in the film is characterized by his energetic delivery, expressive body language, and the use of pauses for comedic effect. His ability to engage the audience with direct eye contact and rhetorical questions creates an intimate atmosphere, making viewers feel personally involved in his commentary. This dynamic style enhances the emotional resonance of his material.

What personal experiences does George Carlin share during his routine?

Throughout 'Life Is Worth Losing', Carlin shares personal anecdotes that reflect his views on life and death, including his experiences with aging, health issues, and the loss of loved ones. These stories add a layer of vulnerability to his performance, allowing the audience to connect with him on a deeper level as he navigates the complexities of life.

Are there any recurring themes or motifs in Carlin's jokes throughout the film?

Yes, recurring themes in Carlin's jokes include the absurdity of societal expectations, the hypocrisy of organized religion, and the critique of consumer culture. He often uses dark humor to explore these motifs, emphasizing the contradictions and ironies present in everyday life, which resonate with the audience's own experiences.

How does George Carlin address the concept of mortality in his routine?

In 'Life Is Worth Losing', Carlin addresses mortality with a blend of humor and poignancy. He reflects on the inevitability of death, the fear surrounding it, and the absurdity of how society handles the topic. His candid discussions about dying and the afterlife are laced with humor, allowing him to confront a heavy subject while still engaging the audience in laughter.

Is this family friendly?

"George Carlin: Life Is Worth Losing" is not considered family-friendly due to its explicit content and themes. The stand-up special features several potentially objectionable aspects, including:

-

Strong Language: Carlin uses frequent profanity throughout his performance, which may not be suitable for children or sensitive viewers.

-

Adult Themes: The material addresses complex and often dark topics such as death, mental health, and societal issues, which may be upsetting or difficult for younger audiences to understand.

-

Cynical Humor: Carlin's comedic style includes a heavy dose of cynicism and satire, which may not resonate well with all viewers, particularly those who prefer lighter or more optimistic content.

-

Graphic Imagery: Some of the jokes involve graphic descriptions or scenarios that could be disturbing to sensitive individuals.

-

Controversial Opinions: Carlin expresses strong opinions on various social and political issues, which may provoke discomfort or disagreement among viewers.

Overall, the content is aimed at an adult audience and may not be appropriate for children or those who are sensitive to such themes.