Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

The story opens in the year 1649, on a gray English morning when the roads are slick with mud and the air still tastes of gunpowder and fear. A narrator's voice sets the stage: "In 1649, the English Parliament had executed Charles I and England became a republic under the oppressive reign of General Oliver Cromwell, backed by the army. The king's son, Charles II, made repeated attempts from France to regain the throne." England is a kingdom without a king, held in an iron grip by Puritan soldiers and scheming politicians, but whispers on the wind already speak of restoration.

Across the English countryside, a small coach rattles along a narrow road, escorted by a handful of Royalist Cavaliers. Inside, traveling in plain dress, is King Charles II himself, not yet crowned, his long dark hair tucked beneath a hat, his quick eyes scanning the hedgerows for danger. He is on an "exploratory tour" of his own future kingdom, testing whether his people are ready to bring him back from exile in France. His companions, loyal Cavaliers, ride close, one hand always near their sword hilts.

From behind a distant rise comes the thunder of hooves. The Cavaliers stiffen. A troop of Roundhead cavalry, soldiers of Cromwell, bursts into view, their iron helmets catching the pale light, their banners snapping in the wind. Muskets are raised; a shout goes up. They have found the fugitive prince.

Shots crack across the road. A ball slams into the coach, blowing a splintered chunk of wood past Charles's shoulder. Horses rear and scream; a guard falls from the saddle. The coach lurches, nearly overturning in the ditch. The Roundheads close in, determined to seize the man they still call "Charles Stuart."

Just as the trap seems complete, another sound cuts through the chaos: the lone, sharp report of a pistol from behind the Roundheads. A dark horseman appears on the crest of the hill, cloak streaming, face hidden behind a black mask. He is elegant in the saddle, every movement controlled, a pistol in one gloved hand, a sword at his hip. This is the notorious highwayman "Silver Blade", already a whispered legend on these roads.

He spurs his horse straight into the flank of the Roundhead column, firing with lethal precision. A soldier pitches from his saddle; another's horse bolts. Silver Blade wheels around, brandishing his sword, his voice ringing: "Stand aside, in the King's name--or in your own blood!" His audacity shocks the Roundheads. In the confusion, Charles's coach lurches forward, the surviving Cavaliers rally to him, and together with the masked stranger they cut a path through the enemy troop.

Gunpowder smoke hangs low as the skirmish breaks apart. Some Roundheads lie motionless in the mud, others retreat in disorder, their shouts fading down the road. The coach, battered but intact, rattles away toward safety. Silver Blade reins in at the roadside, watching long enough to see that the coach has escaped. He lifts one hand in a brief, almost courtly salute, and then, with a flick of his reins, disappears down a side lane, swallowed by mist and hedgerows.

The legend of the masked highwayman who saved the King takes deeper root that day, though only a handful of men know how close England has come to losing Charles II forever.

Time moves forward into the uneasy years of Cromwell's rule and then toward the coming Restoration. Along the same highways, Silver Blade becomes a familiar terror to the proud and greedy. By lantern light and under cold stars, he holds up coaches filled with rich travelers, men who have grown fat on confiscated Royalist estates or on harsh taxes wrung from the poor. He rides out of the dark with twin pistols and flashing sword, efficient and unflinching.

But as he tears open their strongboxes and leather bags, he is not what they expect of a common thief. He spares lives whenever he can. He gives back jewelry to frightened ladies who have clearly not stolen it from anyone. And most of all, he takes heavy purses of coins only to ride later into the villages and cottages that have been stripped bare by Parliamentarian tax collectors, pressing money into rough, grateful hands. Children with hollow eyes stare as he drops coins into their mothers' palms; old men bow over his gloved hand as if he were a knight in a ballad.

In candlelit rooms and smoky taverns, he is cursed as a brigand by the rich and toasted as a hero by the poor. The mask keeps his secret: Silver Blade is in truth Lord Lucius Vyne, a Cavalier nobleman whose lands and fortunes have been shattered by the civil wars. At his own ancestral estate, he is Lord Lucius Vyne, a handsome young aristocrat with the easy manners of his class; on the road, he is the blade of justice for a king not yet on his throne.

Among his kin is Lady Panthea Vyne, a young, delicate-featured woman with large, earnest eyes and a heart as loyal to the Royalist cause as any soldier's. Panthea is an heiress, her name carrying the weight of the Vyne line. In the quiet corridors of her family's country house--the Vyne estate, surrounded by woods and fields--she moves like a shadow, hem of her gown whispering over stone floors. War and politics swirl beyond the walls, but she is trapped in a more intimate struggle.

Her guardians decide her future not by her wishes but by their political fear. To protect what is left of their property under Cromwell's grim regime, they arrange a marriage for her, not to a kindly neighbor, but to a man of power on the opposite side: Lord Drysdale, a Parliamentarian officer and tax collector. Drysdale is no romantic figure. He is a hard-faced man, his eyes as cold as the coin he hoards, his mouth set in an almost permanent sneer. He wears the plain, severe clothes of Cromwell's faction, but his coach is heavy with the glitter of other people's money.

Panthea stands at the altar beside him in a haze of incense and candlelight, her hands clasped so tightly her knuckles are white. She submits to the vows with the hollow obedience of someone who has been told there is no other choice. In the weeks that follow, the full depth of her mistake becomes clear. Drysdale is not just emotionally distant; he is brutal. He treats her like property, an adornment for his status and a body he may use or hurt at his whim.

When he rides out across the countryside to collect taxes for the Republic, he drags her with him, as if to display his conquest. She sits inside his finely appointed coach, its interior lined with dark wood and leather, while outside his agents squeeze yet more coins from already-broken villagers. Bags of gold pile up beneath the seats--four heavy sacks, their weight almost a physical presence--taken "in the name of Parliament," but in truth as much for Drysdale's personal greed as for Cromwell's treasury.

One chill day on the open road, Panthea sits opposite Drysdale in the coach, her small dog curled trustingly in her lap. Outside, the landscape is bleak, winter-stripped trees clawing at the sky. Inside, Drysdale's mood is black. He leans toward her, his breath harsh, a hand sliding where she does not want it. She recoils, eyes wide with disgust and fear, clutching the dog tighter.

"Do your duty, madam," he growls, his fingers digging into her arm. She twists away, choking out, "You are hurting me." He answers by tightening his grip, enjoying the bruise he knows he is making.

A musket cracks outside. A ball screams past the window, smashing the wood just beside Drysdale's head, showering them both with splinters. Panthea screams; her dog yelps and then falls silent in her arms. The coach shudders to a halt, horses neighing in panic. Drysdale shouts for his men. The door is wrenched open, cold air flooding in.

Framed in the doorway is a figure Panthea has only ever heard of in frightened whispers: a tall rider in a dark coat, pistol drawn, a black mask obscuring his eyes and cheekbones. The Silver Blade stands there, outlined against the sky like death itself come to call.

"Your journey ends here, my lord," he says, voice smooth and controlled. His gaze drops for a heartbeat to Panthea's pale face, her tear-streaked cheeks, the limp, bloody body of her dog in her lap. Something sharpens in his posture.

Drysdale, enraged at this interruption, reaches for his sword and lunges out of the coach. "You dare to threaten a servant of Parliament?" he snarls. Panthea can feel her heart hammering in her chest. She clutches her dead pet, the grief almost physical, and forces her voice out in a shaky whisper toward the masked stranger.

"He is… the best swordsman in England," she warns, desperation bleeding into the words. She has no idea why she warns this outlaw; she only knows that she cannot bear to see yet another man die before her eyes.

Silver Blade glances back at her briefly, then at Drysdale. "Then England has grown careless with superlatives," he replies softly.

Drysdale's blade flashes free. They step away from the coach into the open road, mud sucking at their boots. The coachmen hover, terrified, hands frozen on reins and muskets. Panthea, still trembling, slides to the edge of the carriage door, holding the frame to steady herself as she watches.

Steel rings out as the duel begins. Drysdale attacks with vicious energy, thrusting and slashing, his swordsmanship precise and brutal. Silver Blade parries, his movements economical, almost lazy at first, as if testing his opponent. The road is a narrow stage; the hedges and coach hem them in, forcing close-quarters combat.

Panthea's breath comes in ragged gasps. Every time Drysdale's blade whistles close to the highwayman's throat, she flinches. Every time Silver Blade ripostes, sending sparks from Drysdale's guard, her heart leaps with secret, terrified hope. The sound of their boots in the mud, the chime of steel, and Panthea's muffled sobs fill the cold, empty morning.

At last, Drysdale overextends on a furious lunge, driven more by pride than by skill. Silver Blade sidesteps, his cloak swirling, and with a swift, ruthless motion, he runs Drysdale through. The saber slides into Drysdale's chest; his eyes widen in shock. He staggers, looking down at the blade as if unable to believe it.

"So much for the best swordsman in England," Silver Blade murmurs.

Drysdale collapses onto the muddy road, the life draining out of him, his blood mingling with the brown water in the ruts. His chest rises once, twice, then stills. Lord Drysdale is dead, killed in fair combat by Lucius Vyne, the Silver Blade. This is the first and most important on-screen death: a brutal husband felled by the man who has come, unknowingly, to rescue his wife.

Panthea stares at the corpse of the man who has terrorized her, shock and relief warring inside her. She nearly drops the small dead body of her dog as another sob breaks free. Silver Blade wipes his blade on Drysdale's cloak and turns toward the coach.

The coachmen stand frozen, pale and shaking. Silver Blade levels his sword lazily toward them. "Not a word of this," he says, his tone suddenly hard as iron. "On pain of death." The coachmen nod, swallowing hard. They know he means it.

He steps into the coach beside Panthea. Up close, she can see only his mouth and chin beneath the mask, but his eyes, though hidden, seem to burn into her. He looks down at the dog in her lap.

"I am sorry," he says quietly. "He did not deserve this."

Together, in a small patch of grass by the roadside, they dig a shallow grave with their hands. Panthea's fine gloves are soon caked in dirt, but she barely feels it. Silver Blade kneels beside her, his sword laid aside, and helps her lower the limp body of the animal into the earth. Panthea's tears fall onto the small bundle of fur.

"You have lost much," he says softly, a kind of tenderness in his voice that surprises her. "A husband's kindness, a faithful friend."

"I never had the first," she answers bitterly. "And the second was all the love I was allowed."

He covers the body with earth, his gloved hands steady. For a moment, the fierce highwayman is simply a man offering comfort at a grave. When they stand, she sways a little. He catches her elbow lightly to steady her.

Back at the coach, Silver Blade begins to search its interior. Beneath the seats he finds the heavy bags of gold, four in all, their leather bulging. He tugs one heftily; it is heavy enough to bruise. He looks at Panthea.

"This is what he took from them?" he asks.

She nods weakly. "From everyone," she says. "He… he said it was for Parliament. For Cromwell."

"And for himself," Silver Blade replies, his tone falling into cold contempt. He unknots the ties of the sacks, letting a few coins spill through his fingers. Gold gleams dull in the weak daylight. "Stolen from those who had nothing left to give."

He makes his decision swiftly. He loads two of the four bags back into the coach, setting them near Panthea's feet. "These will return to your house," he tells her. "Your husband is dead; you will need protection. Let them think you benefitted from his… service. It will buy you time."

He swings the remaining two bags over his shoulder. "These," he says, "go back to those from whom they were taken."

Panthea looks at him, startled. "You… you give it back?"

"I steal only what was stolen," he answers simply. Then, as she watches him, he leans in a little closer, lowering his voice so the coachmen cannot hear. "And your brother," he says, "is not dead."

She stares at him, eyes suddenly alight. "But he told me--Drysdale said--"

"He lied," Silver Blade whispers. "Your brother lives."

Hope detonates in her chest like a new sunrise. Drysdale's control over her had rested partly on that lie, on convincing her that her blood kin were gone and only he remained. With a few words, Silver Blade has shattered that prison.

"Why?" she whispers. "Why are you telling me this?"

He studies her for a moment, the corners of his mouth almost softening. "Because you have been a prisoner in a gilded cage," he says. "And I have made a career of unlocking cages."

He climbs onto the coach seat and orders the shaken coachmen to drive. Under his guard, the coach returns to the Vyne estate, where Panthea is gently escorted to her familiar home. There, he leaves her with the two bags of gold, their gleam a silent promise of temporary safety and future peril. He mounts his horse and rides away into the dusk with the other two bags, to return the money to the poor from whom it was stolen, an invisible benefactor restoring stolen lives.

The death of Lord Drysdale on that muddy road does not end Panthea's troubles. Instead, it becomes the seed of a future accusation, the dark story that will one day be twisted into a charge of murder.

Years pass. Cromwell's tyranny falters. The tide of history turns. In 1660–1661, amid great rejoicing and ceremony, King Charles II is restored to the English throne, his return hailed with bonfires and bells. London bristles with new life. The somber Puritan dress gives way to lace and ribbons; taverns overflow; courtiers flood back to the palaces.

At the heart of this flowering is the court of Charles II in London, likely at Whitehall, a glittering hive of intrigue, music, and scandal. Here, candlelight glows on polished floors; fans flutter; the rustle of silk and the murmur of gossip fill long galleries. The King, now secure in his power, is charismatic and clever, his reputation for wit and sensuality already well-earned.

Among the luxury of court, one woman shines particularly bright: Barbara, Lady Castlemaine, the King's famously beautiful mistress. Barbara is all dark eyes and raven hair, set off by gowns that push the boundaries of propriety, her laughter low and intoxicating. She is ambitious, accustomed to the King's favor, and jealous by instinct. Power and pleasure are her elements. She is used to being the center of attention and does not easily forgive rivals.

Into this world, after her widowhood, comes Lady Panthea Vyne, now free from Drysdale's tyranny but marked by the trauma of her marriage and the secret of how it ended. She arrives at court with cautious grace, her beauty unsullied by the years of fear. Word of her loyalty to the Royalist cause and her sufferings under Cromwell's regime precede her. Charles, ever fond of stories of devotion to his person, is inclined at once to favor her.

One evening, at a gathering in a great chamber hung with tapestries, Panthea stands a little apart, watching the musicians. She is dressed modestly but with taste, her eyes thoughtful. The King approaches her with two nobles in tow. He smiles, that famous smile that can disarm enemies and charm the most rigid Puritan.

"Lady Panthea Vyne," he says, inclining his head. "I am told you have suffered for my crown."

She drops into a graceful curtsey. "Your Majesty," she answers softly. "If I have suffered, it is nothing compared to seeing England restored to you."

Her quiet dignity touches him. He chats with her, asks about her family, about the countryside she calls home. As they speak, over his shoulder, Lady Barbara Castlemaine watches, her fan stilling. She observes the way the King's gaze lingers on Panthea's face, the way his posture relaxes when she speaks. A flicker of cold calculation crosses Barbara's lovely features.

Later, in one of the mirrored withdrawing rooms, Barbara glides up to Panthea, her smile icy. "You are far from your hedgerows, Lady Vyne," she purrs.

Panthea inclines her head politely. "I am honored to be at court, Lady Castlemaine."

"Are you?" Barbara's eyes sweep over her gown, her modest jewelry. "Be careful, my dear. The court can be… unforgiving to innocents. One wrong step and it will chew you up."

Panthea meets her gaze steadily. "I shall endeavor not to be in anyone's way," she replies.

"That would be wise," Barbara says, and drifts off to the King's side, where she reclaims her usual place, laughing a little more loudly than before.

Another figure at court watches these dynamics with interest: Sir Phillip Gage, a powerful, dangerous man in rich brocade, his eyes as sharp as a hawk's. Gage is associated with the dirtier side of politics--intimidation, quiet violence, the sort of thing that leaves no trace in official records but plenty of whispers in corridors. He is close to Barbara, whether as ally, lover, or hired blade; his exact tie is not publicly spelled out, but his presence at her shoulder is unmistakable.

Panthea navigates this world as carefully as she can, trying to maintain her dignity and not attract undue jealousy. But fate, and her heart, have other plans.

On the roads beyond London, Silver Blade still rides. Even in the age of Restoration, not all injustice has vanished. There are still tax collectors who skim from the coffers, judges who sell verdicts, men who think their Parliamentarian past or their new Royalist coats make them untouchable. Silver Blade continues his work, robbing the rich who have grown too comfortable in their corruption and slipping his loot under cottage doors.

During one of these robberies, along a stretch of road bordered by hedges in full summer bloom, he stops a grand coach whose owner is rumored to have boasted at a dinner that he never pays what he owes. The driver hauls on the reins at the sudden looming figure in the road, pistol raised. The horses rear, snorting.

Silver Blade steps forward, cloak flapping dramatically, and calls, "Stand and deliver!"

The coach door opens. The occupant leans out, outraged… and Silver Blade's breath catches. Sitting inside the coach, framed by velvet curtains, is Lady Panthea Vyne. She grips the doorframe, eyes wide with shock, recognizing the masked stranger who once killed her husband and buried her dog by the roadside. The memory of his voice whispering that her brother still lives comes back like a ghost.

"You?" she breathes.

He stares at her for a moment, then laughs softly, bowing with a flourish. "My lady," he says. "We really must stop meeting on the king's highway."

Her instinct is to be afraid, but her heart does something else entirely. In that first rescue, when he stood between her and Drysdale, something in her soul had already recognized him as her deliverer. Now, in the safety of a new life, away from Drysdale's cruelty, that recognition blooms into something like love.

The robbery that follows is strange, half farce and half courtship. He demands the purse of the coach's actual owner; he tosses a few coins back in when he sees how truly frightened the man is. Panthea watches the entire thing with an odd, giddy flutter in her chest. When opportunities present, they steal moments of conversation. She asks him, "Why do you risk your life like this?" He shrugs lightly. "Some men were born to sit on thrones, my lady. Others to haunt forests. I find the open road… liberating."

It is during these encounters that Panthea begins to see past the mask to the man beneath. His humor, his compassion, the way he speaks of justice rather than revenge--all of it draws her in. And though he holds a pistol and stands outside the law, he treats her with a courtly respect no one else ever has.

Gradually, Lady Panthea Vyne falls in love with the handsome highwayman, the outlaw whose code is more honorable than many lords at court. When she is back in London, among chandeliers and gossip, she finds herself thinking of a masked rider on a lonely road, of wind in her hair and his hand steady at her elbow. She dreams of him; she blushes when his name is whispered among servants.

Their paths cross again, and each time the bond deepens. She confesses little pieces of herself; he listens, his eyes softening beneath the mask. He reveals hints of his own nature, if not yet his name. The tension between her life as a court lady and his as an outlaw becomes a quiet, constant ache between them.

But this is not a world that lets such romances flourish unchallenged. At court, Barbara Castlemaine's resentment hardens into hatred. She senses that Panthea is not simply another pretty face; she is a woman the King respects and perhaps might even come to care for more deeply than Barbara would like. Worse, Panthea carries an air of tragic virtue that makes Barbara's own ruthless climb seem tawdrily exposed.

In hushed corners, Barbara begins to inquire about Panthea's past. She hears vague stories: a brutal husband, a journey, a mysterious death. Curious, she presses further. It is then that she learns of the coach incident years before, when Lord Drysdale died on the road, and of the rumored presence of a masked highwayman.

The tale is fragmented, passed through servants' lips and old soldiers' memories. But it is enough. Barbara's mind, sharp as a dagger and twice as cold, seizes on it. Here, she realizes, is a weapon. A dead husband, a highwayman, unexplained gold at the Vyne estate: all the elements of a scandal--and perhaps even a charge of murder.

She resolves to destroy Panthea.

Her first step is to find someone who was there. With the patience of a spider, she has her agents comb the King's Guard barracks and the old rosters of Drysdale's men. At last they discover that one of the coachmen from that fateful journey survived and now serves as a sergeant in the King's Guards in London.

Barbara arranges a private meeting. It takes place in a dim side chamber, lit only by a few candles guttering in wall sconces. The sergeant, still wearing the uniform of the King's household troops, stands awkwardly before her, hat twisting in his hands. He recognizes the power in front of him; Barbara's reputation precedes her.

"You drove Lord Drysdale's coach, some years past," she begins smoothly.

"Yes, my lady," he answers, unsure. "I… I did."

"And he died upon the road," she continues. "In the company of his wife and a certain highwayman. Is that not so?"

The sergeant's eyes flicker. "I… cannot say, my lady."

She smiles, but there is no warmth in it. She moves closer, the scent of her perfume thick in the small room. "You can," she says. "And you will." From her sleeve she produces a purse, its clink unmistakable. She lets it drop onto the table between them, the coins inside gleaming faintly.

"You are a soldier now," she purrs. "But soldiers do not live forever. Perhaps you would like to leave something for your children. Or your creditors."

He swallows hard, staring at the purse. Then she leans forward, her tone turning iron. "You will say," she instructs, "that Lady Panthea Vyne conspired with this highwayman to murder her husband and steal the gold he carried. You will swear that you saw it with your own eyes. And in return, you will have my protection--and my gratitude."

His conscience quails, but the pull of gold and the fear of crossing such a powerful woman are stronger. At last, he nods. His soul is not worth as much to him as his skin.

Thus, Barbara Castlemaine buys perjury, turning a frightened witness into the instrument of her revenge. The stage is set for Panthea's fall.

As Barbara weaves her web, Panthea's life with Lucius--still unknown to her as such--is moving toward a dangerous intersection. In the countryside, royal agents and local magistrates are growing ever more determined to catch the bold Silver Blade, whose exploits, though romantic to the poor, are an embarrassment to a regime trying to project stability. Men like Sir Phillip Gage begin to direct their attention toward flushing the highwayman out; traps are laid, ambushes planned. Every ride on the dark road becomes more perilous.

One night, perhaps in late 1660 or early 1661, word reaches Panthea--through a servant loyal to her, or through the tangled channels of court gossip--that a detachment of troops is lying in wait along a certain stretch of highway, guns primed, determined to bring Silver Blade down at last. Her blood runs cold. She knows his habits well enough by now to realize that he will very likely pass that way, unsuspecting.

If he rides into that trap, he will die. The thought of his body broken in a ditch, his mask torn away, is unbearable to her.

Panthea makes a fateful choice. She will go to him.

Under cover of darkness, she slips away from the safety of her London lodgings, her cloak pulled tight, her maid wringing her hands in the doorway. She mounts a horse with the awkward determination of a woman not raised in the saddle but driven by love. The hooves drum on the cobbles as she rides out of the city and into the countryside, guided by memory and desperate instinct.

The wind lashes her hair; branches claw at her sleeves. Her heart pounds not only from the ride but from fear--of the soldiers, of discovery, of what she is admitting to herself by doing this. She rides not as a noblewoman returning to an estate, but as a lover racing against time.

Along the dark ribbon of the highway, Silver Blade rides as well, oblivious to the jaws closing around him. Perhaps he hums softly to himself; perhaps he is thinking of Panthea's face, of the way she smiled one afternoon when he handed a purse of money to a widow right in front of her. In the trees above, soldiers load their muskets, ordered by a hard-voiced officer--likely a man in the orbit of Sir Phillip Gage--to wait until the highwayman is within the kill zone, then fire.

Panthea sees the faint glint of metal in the branches ahead, the unnatural stillness of men pretending to be part of the landscape. She hears a muffled command. Panic slams into her. She digs in her heels, urging her horse faster, calling out into the night.

"Silver Blade!" she cries. "Lucius!" The name tears from her lips before she can think, the recognition of his true identity finally on her tongue.

He hears her voice, sharp and urgent, slicing through the quiet. He reins up just short of the trees, eyes narrowing, senses suddenly screaming danger. Panthea's horse pulls alongside his, nearly crashing into him as she gasps for breath.

"It's a trap," she pants. "They are waiting--in the trees, ahead. They mean to kill you."

In that moment, she lays bare everything: that she cares whether he lives, that she is willing to risk her own safety to warn him, that she knows or at least feels who he truly is beneath the mask. His heart thuds once, heavily. He reaches across and grips her arm, steadying her in her saddle.

"You rode all this way… for me?" he asks, incredulous.

"How could I do anything else?" she replies, voice breaking. "I… I love you."

The words hang in the cold air between them, incandescent and irreversible. For an instant, the world narrows to the look in his eyes, the catch in her breath. Then a musket fires from the trees, shattering the moment. The ball whistles past, throwing up a spray of dirt at his horse's feet.

"Go!" he shouts, instincts snapping back. He wheels his horse, grabbing her reins, dragging her with him as he spurs into a gallop in the opposite direction. Shots explode in the branches; soldiers curse as their carefully prepared ambush dissolves into chaos, their target already retreating beyond effective range.

Panthea's warning has saved his life; as the later summaries put it, "she rides to warn him and saves the day after declaring her love for him." Together they plunge off the main road, into the safety of the woods, branches whipping at their cloaks, their horses sure-footed on the leaf-strewn paths.

When at last they slow, breathless in a clearing washed in pale moonlight, Silver Blade swings down from his saddle and helps Panthea to the ground. She stumbles; he catches her, his hands warm even through gloves.

"Panthea," he says, and this time he speaks her name without title. "You should not have done that."

"I could not let you die," she says simply. "Do you not see? If you die, part of me dies too."

He stares at her, the mask suddenly feeling like a lie he cannot sustain. Slowly, he lifts a hand to his face and pulls the black cloth away. Beneath it, revealed in the silvered light, is Lord Lucius Vyne, her cousin, the nobleman she has known half her life and yet never truly seen.

"Lucius," she whispers, a half-sob, half-laugh. Memories cascade through her: childhood glimpses at family gatherings, rumors of his losses in the war, the nagging familiarity she always felt beneath the mask. It all falls into place. Lucius, Silver Blade--they are the same man, the man she has loved in two different guises.

"I should have told you sooner," he says, regret flickering in his eyes. "But as Silver Blade I could fight for what the King could not openly defend. As Lucius Vyne, I am supposed to sit in drawing rooms and pretend none of it matters."

She reaches up and touches his face, fingertips tracing the line the mask had hidden. "It matters," she says. "You matter. To me."

He draws her into his arms, and in that moonlit clearing, with danger still prowling the roads beyond, they seal their love with a kiss--a promise that whatever lies ahead, they will face it not as a lady and a highwayman, but as Panthea and Lucius together.

Their joy is fragile. Back in London, King Charles II prepares for a diplomatic journey to France, leaving his court for a time in the hands of ministers and courtiers who may not share his leniency or his affection for certain subjects. Before he leaves, there is a flurry of farewells, of last petitions granted and postponed.

Panthea sees him one final time before his departure, perhaps in a sunlit gallery, where he compliments her composure and jokes that he expects her to keep the court honest in his absence. She smiles and curtseys, but inside she feels a chill. The King's presence has been a shield, however thin, against the full malice of Barbara Castlemaine. With him gone, that shield weakens.

Barbara watches the King's coach roll away from Whitehall, wheels throwing up dust, and smiles to herself. Without Charles's sharp eye and impulsive mercy at hand, she can move more freely. Her plan, long nurtured, is ready to spring.

Not long after the King's departure, Panthea is arrested. It happens with cold ceremony: a knock at her door at an indecent hour, a file of soldiers in the King's blue and gold livery marching into her lodgings, their commander reading out a warrant. She stands in her nightgown, hair unbound, hardly able to process the words: she is accused of murder, specifically of having conspired to kill her husband Lord Drysdale and steal the taxes he was carrying.

She is taken from the house, cloak thrown over her shoulders, neighbors peering from behind shutters. She keeps her head high, but inside terror gnaws. She knows who truly killed Drysdale--and why--but she also knows that the story, as told by Silver Blade, is not something she can easily drag into the light without implicating Lucius.

Thrown into a chilly cell to await trial, Panthea turns the events over and over in her mind, trying to see a path out. None appears.

The trial takes place in a stark law court, its chamber echoing with the scrape of boots and the murmur of spectators. At the far end sits the bench of grim-faced judges in their robes and perukes, representatives of a justice system still half-torn between Puritan harshness and Royalist restoration. Guards line the walls. In the gallery, courtiers and gossips lean forward eagerly; a noblewoman on trial for her husband's murder is sport they relish.

Panthea is brought in, dressed more soberly than usual, her hands bound in front of her. She stands in the dock, the wood rail cold under her fingers. Her eyes scan the room. She sees Barbara Castlemaine, perfectly composed, watching from a prominent seat, Sir Phillip Gage at her side. Their expressions are sphinx-like, but she feels their animosity like heat.

The charges are read out in cruel detail: that she, Lady Panthea Vyne, did, in concert with a masked highwayman, slay her husband Lord Drysdale on such-and-such a day on the king's highway; that she then profited from his death by secreting away the gold he carried; that she has since consorted with that same outlaw, undermining the King's peace.

Panthea speaks in her own defense when allowed, her voice steady but soft. She tells the court of Drysdale's brutality, of his attempt to assault her in the coach, of the musket ball that killed her dog. She describes the appearance of Silver Blade, how he intervened and fought Drysdale in a fair duel. "I did not conspire to kill my husband," she says. "I did not lift a hand against him. I was a terrified witness, nothing more."

The judges listen, but their faces give little away. Words, even true ones, are not enough. What Barbara has is what counts in such courts: a witness.

The sergeant of the King's Guards, once a trembling coachman, now dressed in blue and gold, is called to the stand. He strides forward, trying to appear noble, but sweat glistens at his temples. He swears an oath and begins his rehearsed tale.

He claims that on the road that day, he saw Panthea lean from the coach and speak with the highwayman before the duel, that her face showed not fear but calculation. He asserts that after Drysdale fell, she smiled. He testifies that she accepted the bags of gold with alacrity, as if expecting them. Under Barbara's watchful eye, he swears that in his judgment, she was in league with the outlaw.

Panthea's stomach twists as she listens. Each lie feels like a blow. She wants to shout, to denounce him, but every outburst might only make her appear more unstable, more guilty. Her advocate tries to shake the sergeant, asking why he did not come forward sooner if he believed this, why his story has changed from the one given in early reports. The man stammers, but Barbara's gold and influence steel his resolve; he sticks to his falsehoods.

The atmosphere in the courtroom shifts. Where there had been titillation, there is now a growing murmur of disapproval. A wife accused of killing her husband is one thing; a wife accused of plotting his murder with a brigand for profit is another. Panthea can feel the tide turning against her.

In some shadowed corner of the building, or perhaps hidden in the crowd, Lucius Vyne listens in anguish. As Silver Blade, he is England's most wanted outlaw; as Lord Lucius, he is a noble with just enough rank to gain entry if he is careful. However he manages it, he hears the lies poured over the woman he loves and knows that his own sword stroke on that long-ago road has become the noose around her neck.

Perhaps he meets briefly with Lady Emma Darlington, a sympathetic older noblewoman who believes in Panthea's innocence and tries to intercede where she can. Emma urges caution; Sir Phillip Gage's men are everywhere. But Lucius is torn between his duty to keep himself alive--for Panthea's sake--and the desperate desire to burst into the courtroom and shout the truth.

In the end, he cannot break the frame. The judges confer. When they return, their verdict is as heavy as iron. Whether they explicitly declare her guilty of murder or couch it in more oblique legal terms, the effect is the same: Panthea is condemned, her life placed at the mercy of royal prerogative that is, at this moment, absent.

She is led away from the courtroom, the murmur of the gallery following her like a tide. Some pity her; others relish the scandal. Barbara Castlemaine watches her pass, eyes gleaming with triumph. She has succeeded: Panthea is now officially a murderess in the eyes of the law, her head figuratively already on the block. Whether by gallows or axe, the sentence implies death if not commuted.

Meanwhile, the net tightens around Lucius. As the notorious highwayman Silver Blade, he now stands not only accused of robbery but implicated in the supposed murder of a nobleman and the corruption of a lady of the court. Troops ride with renewed vigor; men like Sir Phillip Gage grow more vocal in the council, arguing that the realm cannot be secure while such brigands roam free. Rumors multiply: that Silver Blade is in league with foreign powers, that he means to embarrass the King, that he leads a band of rebels. Each lie fuels the hunt.

At some point in this dark spiral, Lucius himself is captured--whether by a betrayal among his contacts, by sheer bad luck in an ambush, or by Gage's relentless hounding is not specified in the surviving summaries, but the implication is clear: both Panthea and Lucius face execution. The romance that began in rescue and blossomed in moonlit clearings now teeters on the brink of tragedy.

Word of these events--Panthea's condemnation, Lucius's impending death--crosses the Channel. In France, where he has gone on royal business, Charles II hears troubling news from his homeland: that a woman he favored, who once suffered for him under Cromwell, has been railroaded in a suspicious trial; that a highwayman whose robberies often targeted those the King himself privately disdains is to be hanged. Mixed into the reports is another detail that pricks his curiosity: that Lady Barbara Castlemaine appears to have been unusually active behind the scenes in these prosecutions.

Charles knows Barbara well. He has enjoyed her charms and endured her tantrums. He is also fully aware of her capacity for spite. The idea that she might have used the instruments of royal justice to settle a personal score sits ill with him--especially when the target is Lady Panthea Vyne, whose bearing he admired.

By the time Charles returns to London, the noose is nearly knotted. Panthea's date of execution draws close; Lucius, too, awaits a grim fate as a criminal and alleged killer. In the execution yard or on the steps of a scaffold, preparations are made; crowds murmur, eager to see noble blood on the block again, though this time in the name of royal law rather than Parliament's.

The King does not hurry to the scaffold. Instead, he reasserts his authority where it matters: in the throne room and council chamber, demanding a full accounting. He calls for the trial records, for the testimonies, for the list of those who pressed the charges. He questions judges, demands to hear the sergeant's story firsthand. Under the intensity of royal scrutiny, cracks begin to appear.

It is here, in this phase of the story, that all the threads of revelation come together. Charles learns the details of Panthea's marriage: Drysdale's brutality, his tax-gathering, his abuse. He learns that the duel on the highway was fair, provoked by Drysdale's assault on his wife, not a cowardly assassination. He recalls or is reminded that Silver Blade once saved his own life from Roundheads on that long-ago road.

Perhaps Lady Emma Darlington speaks in Panthea's defense, vouching for her character and hinting at Barbara's animosity. Perhaps Lucius, given a chance to speak as a noble before being executed, lays out the truth of the Drysdale duel, sparing no blame of himself but insisting on Panthea's innocence. The King weighs these accounts against Barbara's version of events and the sergeant's testimony.

When Charles summons Barbara Castlemaine to explain herself, the tide truly turns. He questions her about her involvement with the sergeant, about the bribe she offered. Whether she tries to bluff it out or turns her considerable charms on him, the damage is done: the King has seen the rot beneath the surface.

The sergeant, brought once more before the royal eye, finds his courage failing. Facing the possibility of punishment for perjury--and now with Barbara's protection slipping away--he cracks. Haltingly, he confesses that he was paid to lie, that Lady Panthea did not conspire with the highwayman, that she was as shocked and terrified as any woman would be when her husband fell in a duel she did not ask for.

With that confession, the edifice of the case against Panthea collapses. The supposed "murder" stands exposed as an honorable duel fought by Lucius Vyne to defend a woman from her husband's abuse. The four bags of gold are finally understood in their proper context: Drysdale's hoard of unjust taxes, half of which Lucius returned to the poor, the other half left with Panthea not as plunder but as a buffer against destitution.

Charles II, ever conscious of image but also capable of real mercy, acts decisively. He overturns Panthea's sentence, halting the execution that looms over her. Orders race from the palace to the jail and the scaffold, staying the hangman's hand or the headsman's axe at the last possible moment. Guards burst into her cell, not to drag her to death but to escort her--still blinking in disbelief--into the royal presence.

At the same time, the King addresses Lucius's fate. By the strict letter of the law, Silver Blade is guilty of robbery on the king's highway, an offense that has sent lesser men to the gallows. But the King now knows that Lucius's thefts have largely targeted the corrupt and enriched the poor, that he has protected the King himself, and that the killing of Drysdale was a fair duel in defense of a woman Charles has come to esteem.

In a scene rich with tension and relief, Lucius is brought before the throne, perhaps in chains, head high. Panthea, now freed, may stand nearby, eyes shining with unshed tears. Barbara Castlemaine is present too, pale with fury at seeing her careful work undone. Sir Phillip Gage looms at the edge of the room, understanding that the political ground beneath his feet is shifting.

Charles regards Lucius for a long moment. "Lord Lucius Vyne," he says at last, his voice carrying through the great chamber, "you have given me thanks I did not know I was owed. I am told you once intercepted Roundheads who sought to take my life, that you have relieved my subjects of the burden of unjust taxes, and that you fought a duel to protect a lady of my court from a husband unworthy of her."

Lucius bows as best he can in irons. "I have done what I thought right, Sire," he replies.

"You have also robbed my highways and confounded my officers," Charles continues, the hint of a smile tugging at his mouth. A ripple of nervous laughter runs through the assembly. "Were I less inclined to mercy, your neck would soon be an inch longer than God intended."

He rises slightly from the throne, letting the moment hang, then declares, "But England has had enough of blood on the block. I will not pay back every sin of Parliament with another rope. In recognition of your services to my person and to my people, I grant you a royal pardon." The exact legal term may differ--pardon, reprieve, or clemency--but its effect is the same: Lucius's life is spared.

He orders Lucius's chains struck off. The clink as they fall to the floor echoes like a bell of liberation.

Turning to Panthea, Charles's tone softens. "Lady Panthea Vyne," he says, "you have been wronged--by a husband, by a court, and by one who once shared my favor." He glances at Barbara Castlemaine, whose face burns with humiliation. "Let it be known that you are innocent of any crime. Your name is restored, your lands and honors secure."

Panthea sinks into a deep curtsey, tears spilling freely now. "Your Majesty," she whispers, voice thick with emotion. "I have no words."

"Then do not waste breath on them," he answers kindly. "Use it instead to live, and to be happy."

As for Lady Castlemaine, the film's public summaries do not record a dramatic on-screen death or exile. Her punishment, such as it is, is social and political defeat. In the hushed silence of the court, her schemes exposed, she stands alone. The King may not rant at her; his rebuke is more subtle and more devastating. He withdraws his full favor, treats her henceforth with cool politeness rather than unguarded intimacy. Within a court like Charles's, such a shift is a kind of death: the slow withering of influence, the creeping irrelevance.

Sir Phillip Gage, too, feels the change. Whatever plan he had to ride Lucius's downfall to greater power now crashes. Whether he fades into the background or suffers some quieter disgrace is not detailed, but he is no hero here; his allies have lost, and thus so has he.

In the wake of all this, the final scenes focus where the story's heart has always truly been: on Lady Panthea Vyne and Lord Lucius Vyne, the lady and the highwayman whose love survived war, abuse, jealousy, and the hangman's shadow.

They meet again not in a prison or in a shadowed wood, but in the open light, perhaps in the gardens of the royal palace or in the restored peace of the Vyne estate. The sky is clear, the air softer. Panthea walks along a gravel path, fingers brushing the tops of hedges, the echo of her footsteps a rhythm of freedom. Lucius approaches, no longer masked, no longer hunted. He is dressed as a nobleman again, but there is still a hint of the rogue in his eyes.

They stop a few feet apart, the weight of all they have endured between them. For a moment, words fail. Then Panthea smiles, a small, tremulous thing that grows as she looks at him.

"You are late," she says, voice teasing, echoing some earlier exchange on the road.

"I was detained by a king and a few old ghosts," he replies.

They close the distance. He takes her hands--now unshackled by marriage contracts or legal bonds--and lifts them to his lips. "Panthea," he says softly, "I rode for the poor and the King. But I lived… for you."

She laughs through her tears. "Then live with me," she answers. "No more masks. No more gallows."

He draws her into his arms, and they stand there for a long moment, the world falling away. In the background, the kingdom slowly rights itself from years of upheaval. Charles II goes on ruling with his customary blend of charm and cynicism; Barbara Castlemaine seeks her footing in a court that has seen her fallibility; justice, bent by jealousy, has been straightened at least in this one case.

But for Panthea and Lucius, what matters is simpler. They have cheated death. Drysdale's cruelty lies buried on that muddy road where Lucius killed him in a fair fight. The gold that symbolized theft and corruption has been returned to those in need or transformed into a dowry for a new beginning. The lies Barbara bought with coin have been burned away by truth.

In the film's closing images, perhaps we see them riding together along a familiar highway, this time not as a victim and her rescuer but as equal partners, the morning sun gilding the landscape instead of the grim dawn of Drysdale's last day. Lucius may look at the road with a half-smile, remembering all his exploits as Silver Blade, and then at Panthea, deciding that no treasure he ever stole glittered as brightly as the life ahead with her.

The camera lingers on their figures receding into the distance--no masks, no soldiers in pursuit, only the long, open way of the future. The tale that began in the shadow of a king's execution and on a road spattered with blood ends in restoration not just of a throne, but of honor, love, and justice.

What is the ending?

In the ending of "The Lady and the Highwayman," the story culminates in a dramatic confrontation between the highwayman, Captain James, and the authorities. After a series of thrilling escapades, Captain James is captured but ultimately escapes with the help of Lady Eleanor. The film concludes with the couple riding off together, symbolizing their love and newfound freedom.

Now, let's delve into the ending in a more detailed narrative fashion.

As the final act unfolds, the tension escalates in the dimly lit streets of London. Lady Eleanor, having been torn between her duty and her love for Captain James, finds herself at a crossroads. She is determined to save him from the clutches of the law, which has been relentlessly pursuing the notorious highwayman.

In a pivotal scene, Eleanor disguises herself and sneaks into the prison where James is being held. The atmosphere is thick with suspense as she navigates the dark corridors, her heart pounding with fear and hope. She reaches James's cell, and their eyes meet, igniting a spark of love and determination. James, though weary and battered, is filled with renewed strength at the sight of Eleanor. They exchange whispered words of encouragement, their bond evident in the way they hold each other's gaze.

Meanwhile, outside the prison, the authorities, led by the ruthless Sir John, are preparing to execute their plan to capture James once and for all. Sir John, driven by a personal vendetta against the highwayman, is relentless in his pursuit. He believes that capturing James will not only bring him glory but also rid the streets of the chaos that the highwayman represents.

As Eleanor and James plot their escape, the tension mounts. They devise a plan to create a diversion, allowing them to slip past the guards. In a heart-stopping moment, Eleanor sets off a small explosion, causing chaos in the prison yard. The guards rush to investigate, and in the ensuing confusion, James seizes the opportunity to break free from his cell.

The couple reunites in the shadows, their hearts racing as they make their way through the labyrinth of the prison. They share a brief moment of tenderness, knowing that their love has brought them to this point of danger and excitement. With every step, they are acutely aware of the stakes; their lives depend on their ability to evade capture.

As they reach the outer walls of the prison, they encounter Sir John and his men. A fierce confrontation ensues, with James fighting valiantly to protect Eleanor. The scene is charged with emotion as James, fueled by love and desperation, faces off against Sir John. The clash of swords and the shouts of men fill the air, creating a cacophony of chaos.

In a climactic moment, James manages to outmaneuver Sir John, delivering a decisive blow that allows them to escape. They flee into the night, the moonlight illuminating their path as they ride away on horseback. The freedom they sought is finally within their grasp, but not without the weight of the danger they leave behind.

The film concludes with a poignant scene of James and Eleanor riding off into the horizon, their silhouettes framed against the dawn. They are free, but the journey ahead is uncertain. Their love has triumphed over adversity, and as they look at each other, there is a shared understanding that they will face whatever comes next together.

In the end, Captain James and Lady Eleanor find solace in their love, having defied the odds and escaped the clutches of the law. Sir John, left behind, is left to grapple with his defeat, a reminder of the consequences of obsession and vengeance. The film closes on a note of hope, emphasizing the power of love and the pursuit of freedom against all odds.

Is there a post-credit scene?

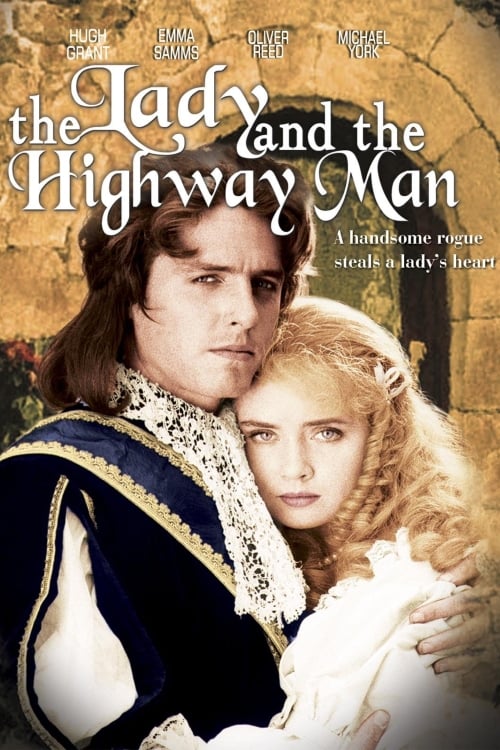

The movie "The Lady and the Highwayman," produced in 1988, does not contain a post-credit scene. The film concludes its narrative without any additional scenes or content after the credits roll. The story wraps up with the resolution of the main plot, focusing on the romantic and adventurous journey of the characters, particularly the relationship between the lady, played by Lysette Anthony, and the highwayman, portrayed by Christopher Villiers. The ending emphasizes their triumph over adversity and the rekindling of their love, leaving the audience with a sense of closure.

Who is the main female character in The Lady and the Highwayman and what motivates her actions throughout the film?

The main female character is Lady Sarah, portrayed by Lysette Anthony. She is a spirited and independent woman who becomes embroiled in the dangerous world of highwaymen. Her motivations are driven by a desire for freedom and adventure, as well as her growing feelings for the dashing highwayman, Captain James. Throughout the film, she grapples with her societal expectations and her attraction to a life of excitement and danger.

What is the relationship between Lady Sarah and Captain James, and how does it evolve?

Lady Sarah and Captain James, played by Hugh Grant, share a tumultuous and passionate relationship. Initially, Sarah is intrigued by James's rebellious nature and charm, while James is captivated by her beauty and spirit. As they face various challenges together, including confrontations with the law and rival highwaymen, their bond deepens. Their relationship evolves from mere attraction to a profound connection, as they both confront their fears and desires.

What role does the character of Sir John play in the story, and how does he impact Lady Sarah's choices?

Sir John, portrayed by David McCallum, is a wealthy suitor who represents the societal expectations placed upon Lady Sarah. He is determined to marry her, viewing her as a prize to be won. His presence creates tension in the story, as Lady Sarah feels trapped by his advances and the constraints of her social status. Sir John's pursuit of Sarah ultimately forces her to confront her true feelings for Captain James and the life she truly desires.

How does the film depict the conflict between the law and the highwaymen, particularly through the character of Captain James?

Captain James embodies the spirit of the highwayman, a figure who defies the law and societal norms. The film portrays him as a charismatic outlaw who steals from the rich to help the poor, creating a Robin Hood-like persona. His conflicts with the law, represented by various authorities and bounty hunters, highlight the tension between justice and rebellion. James's internal struggle between his criminal lifestyle and his love for Lady Sarah adds depth to his character, as he must choose between freedom and love.

What significant events lead to the climax of the film, particularly involving Lady Sarah and Captain James?

The climax of the film is marked by a series of high-stakes events that test the relationship between Lady Sarah and Captain James. Key moments include a daring rescue where James saves Sarah from Sir John's clutches, and a dramatic confrontation with the law that puts both their lives at risk. As they navigate these challenges, their love is put to the ultimate test, culminating in a tense showdown that forces them to confront their feelings and the realities of their respective worlds.

Is this family friendly?

The Lady and the Highwayman, produced in 1988, is generally considered suitable for family viewing, but it does contain some elements that may be objectionable or upsetting for children or sensitive viewers. Here are a few aspects to consider:

-

Violence and Threats: There are scenes that depict violence, including sword fights and confrontations that may be intense for younger viewers. Characters face threats and danger, which could be unsettling.

-

Romantic Tension: The film includes romantic elements that may involve passionate exchanges and situations that could be awkward for younger audiences.

-

Historical Context: The story is set in a time of social and political unrest, which may include references to class struggles and the consequences of crime, potentially leading to discussions about morality and justice.

-

Emotional Conflict: Characters experience betrayal, loss, and emotional turmoil, which could evoke strong feelings and may be difficult for sensitive viewers to process.

-

Mild Language: There may be instances of mild language or insults that could be considered inappropriate for very young children.

Overall, while the film has adventure and romance, parents may want to preview it or discuss its themes with children to ensure it aligns with their comfort levels.