Ask Your Own Question

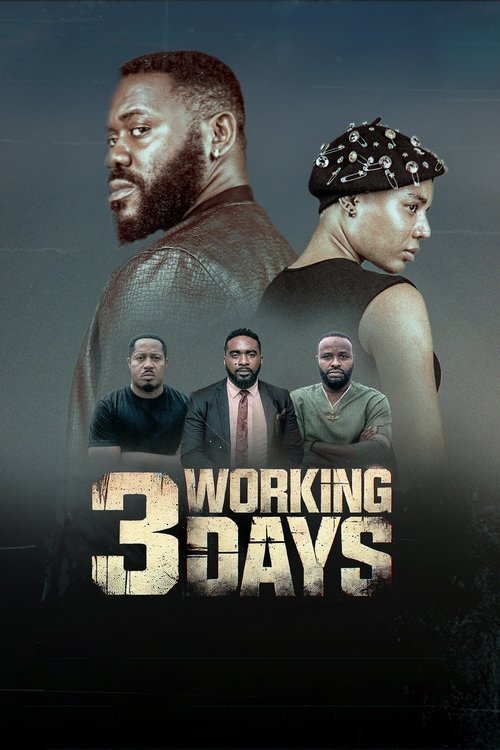

What is the plot?

What is the ending?

In the ending of 3 Working Days, Onari's hostage standoff in the bank finally breaks when the system that has blocked his money relents and his transaction is processed so he can pay for his son's surgery. The police move in, the hostages are released, and Onari is taken away alive, having saved his child but facing the consequences of his actions; the key bank officials survive and must live with what their choices did to him and his family.

Now, in a fuller, step‑by‑step narration:

By the time the ending begins, the bank lobby has become a tight, airless world. Onari, exhausted and frayed, still holds the staff and customers hostage, his gun no longer looking like a weapon of control so much as a last barrier between his son and death. The demand he has repeated all day remains the same: the bank must release his own money so he can pay the hospital for the critical surgery his son needs. His voice is hoarse; his shirt is rumpled and darkened with sweat; his eyes keep flicking to his phone, to the hospital updates that are no longer coming quickly enough.

Across from him, the bank manager and senior staff, who had earlier insisted on "3 working days" for the transaction to clear, stand pale and rigid behind the counters and desks. Their earlier confidence in the rules has drained away under the reality of armed police outside, customers on the floor, and a desperate father who has nothing left to lose. The manager occasionally tries to reason with him--talk of procedures, of the system, of how things "must" work--but those words have lost power in the standoff's final stretch. Every time the manager hesitates, Onari's anger spikes and then collapses back into pleading.

Outside, through the glass doors and windows, armed officers and tactical units wait, forming a semicircle around the bank entrance. Their stance has been constant all day: rifles ready, eyes locked on the main door, trying to track movements inside. Negotiators have been pressing Onari via phone and loudspeaker, urging him to stand down, promising they are "working on it." Each promise of help that drags without result only tightens the coil inside him.

As the final sequence builds, the bank's internal systems, the central processing office, and the wider banking network are finally pushed into urgent motion. Calls that had previously been shuffled, transferred, or brushed aside now happen with a new tone; higher‑level officials become involved. The bank's staff at the branch frantically relay account details and flags on the account, citing the hold that has trapped Onari's funds at the worst possible moment. Someone on the back‑office side finally overrides the blockage. The transaction Onari has begged for, fought for, and threatened for moves through.

Inside the bank, this change arrives almost quietly. A junior staff member, hunched over a computer, sees a status on the screen flip--funds cleared, transaction approved. She freezes, then calls the manager over. He scans the monitor, his face tightening as he realizes that the thing that could have been done much earlier has now been done under the pressure of a gun and a national crisis.

The manager steps slowly out from behind the counter, hands raised to show he poses no threat. He tells Onari that the transfer has gone through, that the money is now available, that the hospital can be paid. Onari does not relax immediately. He demands proof. The manager signals to one of the tellers; the teller prints a slip and shows it to him: transaction successful, amount debited.

Onari takes the slip with shaking hands and stares at the figures. For a long moment there is no movement. His breathing is loud in the quiet lobby. The hostages, scattered on the floor and huddled behind chairs, watch him, some crying, some whispering prayers. The police outside, seeing bodies shift near the windows, tighten their grip on their weapons.

Onari then takes out his phone. His fingers, still unsteady, search for the hospital contact. He calls. There is a ring, and another. Finally, a doctor or hospital staff member answers. The conversation is brief and clipped: he confirms his name, the child's name, the account, the expected payment. On the other end, the hospital confirms the funds have arrived or that confirmation from the bank has been received, and the surgery can proceed.

Hearing this, Onari closes his eyes. For the first time since he stormed the bank, his shoulders drop--not in defeat, but in a heavy, aching release. Whatever happens to him now, his son's chance at life has been secured. He asks one more question about the boy's condition, and the answer he gets is cautiously hopeful: the procedure will go ahead; they will do everything they can. He ends the call and holds the phone against his forehead, silently.

This is the moment when the emotional center of the ending lies: a father who has broken the law to save his child has finally forced a rigid system to move. The tension in the room shifts. The hostages begin to sense that the danger has changed.

But outside, the police cannot read every nuance. They only know that the hostage‑taker has held a bank at gunpoint for hours and that any wrong move could still be fatal. The negotiator calls again, asking Onari to put down his weapon and release the hostages. The manager adds his own appeal. Staff who have been terrified of him all this time now ask him to surrender, saying that his son needs him alive, that his job here is done.

Onari looks at the gun in his hand. Weighed against his son's life, it suddenly feels meaningless. He moves to the center of the lobby, where everyone can see him clearly--police outside, hostages inside. Deliberately, so there is no misunderstanding, he kneels or lowers himself, sets the gun on the floor in front of him, and pushes it away. His hands rise slowly over his head.

One by one, the hostages stand, arms instinctively up, filing toward the door as officers shout instructions from outside. The bank's staff--tellers, customer service reps, security, the manager--join the stream, each of them crossing the threshold from the hostage space into the control of the authorities. Some glance back at Onari as they pass: a mixture of fear, relief, and an uneasy recognition that they have witnessed the breaking point of a man crushed by a system they help operate.

As the last hostages exit, the police move in. A tactical team enters cautiously, weapons trained on Onari even though his hands are still raised. They shout commands; he complies, turning, lying down, allowing himself to be handcuffed. There is no resistance. The earlier frantic energy is gone; his movements are slow, almost detached, as if his mind is already back at the hospital corridor, waiting outside an operating room.

They lift him to his feet and escort him out of the bank. Cameras may be present at a distance, news crews capturing the image: a father in cuffs, clothes disheveled, face strained, being led away from the institution he forced to release his own money. He does not shout or argue. As he is placed into the police vehicle, he asks--either to the officers or to no one in particular--about his son again. If there is any update, it has not yet reached him.

From here, the film closes the circle on the main characters' fates:

Onari: He is arrested and taken into custody, alive. The film makes it clear that he will face legal consequences for the armed takeover of the bank and the hostage situation, but he has achieved what drove him there: the bank has released the money in time for his son's surgery. His ultimate fate beyond arrest--trial, sentence--is left outside the frame, but his immediate fate is clear: he is no longer free, yet he has acted in a way he believes a father must when every legal path fails his child.

Onari's son: The funds for the operation have finally reached the hospital, and the doctors proceed with the life‑saving surgery. The film frames this as the success that justifies, in Onari's mind, every extreme measure he took. The boy survives the crisis long enough for the medical team to act; the ending centers on the certainty that the financial barrier to his treatment has been removed, giving him a fighting chance at life.

The bank manager: He survives physically and walks out of the bank when the hostages are released. His professional and moral position at the end is shaken. He has watched the rules he enforced--insisting on three working days for a transaction and adhering to rigid procedures during a national cash‑scarcity crisis--transform directly into the trigger for a violent standoff. The film leaves him back in the world, no longer in immediate danger, but forced to live with what his decisions contributed to.

Other key bank staff and customers: All the principal hostages who are central to the ending are released alive when Onari surrenders. They are escorted outside by the police and emergency teams, physically unharmed, though emotionally rattled by the hours spent at gunpoint. Their fate is to return to their lives bearing the memory of the incident and a clearer sense of how fragile safety can be when the system fails someone desperate enough.

As the last sequence closes, the narrative emphasis remains on the contrast between the faceless rigidity of the banking and cash‑scarcity system and the very personal, immediate stakes of a father trying to save his child. The final images hold on the consequences of that clash: a child's surgery funded at last, a father in handcuffs, and a group of bank officials and customers stepping back into daylight, all permanently marked by what unfolded inside the bank over those three working days.