Ask Your Own Question

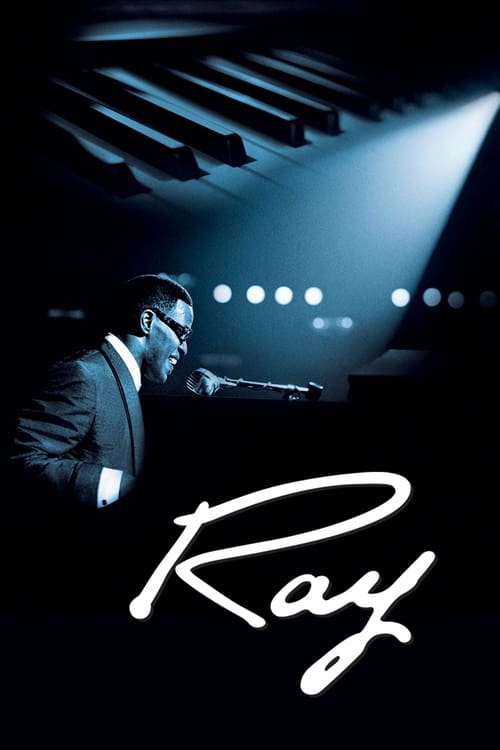

What is the plot?

Ray Charles Robinson is a small, barefoot boy running through red Florida dirt when the story begins, the sun hot and high over the fields of Greenville in the early 1930s. He is maybe five years old, wiry and quick, with sharp eyes that miss nothing, and his little brother George Robinson, younger and smaller, chases him, laughing, through the yard outside their rough wooden shack. Their mother, Aretha Robinson, watches from the doorway, serious-faced and worn by work and poverty, but fiercely attentive. Inside, a cast-iron washbasin brims with water for laundry, the only cool glow in a hard, dusty world.

The afternoon feels lazy, but tension lies under everything--the Jim Crow South, the weight of survival. Aretha sends Ray for something; he darts in and out, always moving, always curious. At one point he hears a muffled splash and turns. George has climbed up on the ledge of the washbasin, reaching for a toy. The wood shifts, the boy's feet slip, and he tumbles headfirst into the basin. There is a hollow thud, then silence.

Ray pauses in the doorway, framed by light, and sees his brother's small legs kicking weakly above the rim. For a second he freezes, stunned, his face twisting in confusion. "George?" he says, the word small and uncertain. The tub rocks, water sloshing. George's legs jerk, then grow frantic. Fear claws at Ray's chest. He takes a step, then another, but something--pure terror, a child's paralysis--locks his body. He stands there and watches, unable to move, as the kicking slows, then stops. The basin is still. The only sound is dripping water and distant insects.

By the time Aretha rushes in, screaming, it is too late. She hauls George's limp body from the water, sobbing and howling, the boy's arms dangling. Ray, rooted in place, stares, his mind scorched by the sight of his drowned brother. George Robinson's death--an accidental drowning caused by his fall into the washbasin--is the first and most haunting death in Ray's life, and Ray feels responsible. No one killed George but chance and a moment of paralyzing fear, yet to Ray it is a sin attached to his name.

In the nights that follow, that little body appears again and again in his dreams. Water seeps into everything--into memory, into music, into the very shape of his fear.

Soon after George's death, Ray's vision begins to blur. At first it is little things: the world fades at the edges, colors dim, shapes double. Aretha notices him bumping into furniture, missing steps. He rubs his eyes, confused, insisting he is fine. But glaucoma is tightening its grip, and by the age of seven, he is completely blind. For Ray, darkness is not a sudden plunge but a slow erasure of light, layered over the grief of George's death.

One day, he falls hard in the yard, crying out. Aretha comes to him, her voice sharp but laced with something unyielding. She will not let pity swallow him. She kneels down close so he can feel her breath.

"Ray," she tells him--this is the line that will live in his bones--"you're blind, you ain't stupid." She orders him to get up, to use his ears, his hands, his nose. "Make it do what it do," she says in essence, teaching him to map the world through sound and touch. She refuses to treat him as helpless, refuses to let anyone coddle him into weakness.

She sends him to a school for the deaf and blind, a wrenching decision, but one she knows will give him a way forward. Before that, he has already discovered the piano, its rough keys and smooth notes a new language beneath his fingers. Learning from an old upright in a neighbor's shack and then more formally at school, he is soon playing anything he hears, his hands dancing over the keyboard with an uncanny, intuitive grace.

But even as music opens a door, his guilt and fear remain. The film returns often to that washbasin, to water glinting and George's body, as if the past is a ghost always waiting just behind Ray's shoulder.

Years pass. America shifts into the 1940s. By 1946, teenage Ray Charles Robinson is already a working musician, playing piano in small bands across the South, including a white country band that wants his sound but not his truth. The bandleader insists he wear dark sunglasses to hide what they call his "damaged" eyes from white audiences, as if the reality of his blindness would be an offense. Ray adapts, sliding the glasses on with a kind of ironic dignity. When curious white folks ask what happened, he spins a fiction with a straight face: "Normandy," he says, claiming he took a direct hit and lost his sight in the war. It is a lie designed to soothe their consciences--and a small rebellion.

Those early gigs are rough: segregated clubs, racist crowds, lousy pay. He learns quickly that he is expected to entertain, not be seen as a full man. Yet on stage, when his fingers find the keys, he steps beyond that smallness, pulling blues and country licks into something electric.

By 1948, twenty-ish and restless, he makes a decision: he will leave Florida and head to Seattle, Washington, as far from Greenville and its ghosts as he can get. Armed with a piano style, a suitcase, and little else, he boards a bus and rides across the country into a world of damp gray skies and neon lights.

Seattle in 1948 is a different universe: the Central District humming with jazz clubs, military men, and working-class Black life. Ray arrives expecting to link up with his friend and musical partner Gossie McKee, a guitarist who left before him, but when he gets to town and hunts through smoky bars, Gossie is nowhere in sight.

One night Ray wanders into a small nightclub, his cane tapping, ears tuned to the murmur of voices and the clink of glasses. This is a rough joint, its stage scratched and dim, its crowd half-listening to whoever is playing. The owner, Marlene André, watches from the bar--a hard, ambitious woman who knows talent when she hears it.

Ray asks for Gossie. Instead, he meets a young, fast-talking trumpeter, Quincy Jones, and eventually links up with a house band that includes Gossie after all. Marlene hears him play once, his fingers turning a simple tune into a rich, layered groove, and her eyebrows rise. This blind kid from Florida can play.

Soon he's part of the band, the music building night after night. But Marlene is not just a patron; she is a hustler. She begins to manage him--on paper to "help" him, in reality to own him. She controls his bookings, his pay, even his bed. She calls him into her office, presses her body against his, and makes it clear that the gig includes sex with her. For a young man hungry for a career and a measure of security, it is both an opportunity and a trap.

Ray, far from home and dependent on others to navigate the sighted world, tries to trust. Marlene handles his checks, giving him only a modest allowance, telling him she is taking care of everything. Gossie, as bandleader, takes extra pay. They assure Ray it's all standard. At first he believes them. He has few options.

But not everyone around Marlene is comfortable with the arrangement. Oberon, a small, sharp man who works for her--quiet, observant, and perhaps more decent than his surroundings--pulls Ray aside one day. He speaks low, away from Marlene's ears. He tells Ray the truth: Marlene and Gossie are bleeding him. They are taking a 35% commission from Ray's money, Oberon says, and on top of that, Gossie is taking double pay as bandleader. Worse, Oberon reveals that Marlene is holding all of Ray's paychecks from the club, doling out a tiny allowance while keeping the rest for herself.

The betrayal lands hard. Ray's face tightens; the familiar childhood humiliation and fear are now joined by adult anger. He realizes he has been lied to, used not just for his body and talent but for his earnings. In the next confrontation, his voice is steady. He calls Marlene on it. She fights back, angry that her control is slipping, but the facts are clear.

He does not scream; he walks. With Quincy Jones at his side, Ray leaves the band and Marlene's club, determined never again to let someone else own him in that way. It is a first major act of self-assertion, a choice that starts to define the man he will be.

Free but broke, Ray needs a break. He meets Jack Lauderdale of Swing Time Records, a burly, businesslike man who sees dollar signs in Ray's sound. Jack offers him a $500 advance--an enormous sum to Ray--and three times what Marlene was paying. Ray signs, seeing not yet the pattern of exploitation that will repeat with labels, but only the open door.

Through Swing Time and the tireless efforts of record producer Milt Shaw, who will later help distribute his records across the United States, Ray begins laying down tracks. At first, they sound a lot like others: smooth Nat King Cole–style vocals, imitation more than innovation. But Ray knows he hasn't found his true voice. Somewhere deep inside, gospel hymns from childhood and Saturday night juke joint rhythms tangle and demand to be fused.

On the road, he starts touring the Black venues of the Chitlin' Circuit, sweats through endless nights in smoke-filled rooms, and meets the woman who will anchor his life. In Texas, sometime in the early 1950s--the film doesn't stamp the exact date, but the sense of postwar, Jim Crow America is thick--he hears a warm, clear female voice and meets Della Bea Antoine.

Della Bea is a preacher's daughter and a singer with calm strength in her eyes. She is not dazzled by him at first; she watches quietly. He flirts, jokes, touches her hand. She senses both his charm and his damage. But there is something about his struggle and his brilliance that draws her in.

On tour in Texas, their courtship moves quickly, a swirl of bus rides, backstage talks, and long phone calls from pay phones between cities. Ray, always pushing forward, asks her to marry him. They do, soon, in the 1950s, and she becomes Della Bea Robinson--the woman who will stand beside him longer and more faithfully than anyone else.

Back in the studio and on stage, Ray begins experimenting with something radical. He takes the call-and-response patterns and passionate melismas of church gospel and lays them over the tight rhythms and suggestive lyrics of rhythm and blues. Della is his muse, love and spirit wrapped together. Out of this combination comes "I Got a Woman," the first song where Ray truly fuses gospel with rhythm and blues into what will later be called soul music. Critics mutter that he is "stealing the Lord's music" for the devil's work, but the crowds can't get enough. Ray Charles, as he is now billed--dropping his last name Robinson for the stage--has finally found his sound.

Tour life grows wilder as the 1950s roll on. In darkened back rooms and cramped dressing areas, older musicians introduce Ray to a new companion: heroin. They show him how to cook it in a spoon, draw it into a needle, and slip it into his veins. The first rush is like an explosion of warmth and calm, quieting the guilt, the visions of drowning, the fear of failure. He tells himself he can handle it, that he is in control. But from that first injection, heroin is a central character in his story, a seductive, lethal presence that will nearly destroy him.

Della senses something is wrong before she knows what. He comes home from tours jittery or dead-faced, sometimes nodding off. When she searches his things one day and finds his drug kit buried in his shaving bag--needles, spoons, the residue of a habit--she is devastated. Her hands tremble as she holds the evidence. He walks in, and she confronts him, her voice breaking but strong.

"Ray, what is this?" she demands.

He tries to downplay it: "It's nothing, Bea. I got it under control."

"You got a baby on the way," she tells him, pregnant with their child. "You can't keep doing this. You can't keep lying."

He refuses to stop. Pride and addiction wrap around him. Instead of throwing the drugs away, he walks out--leaving a pregnant Della sobbing, the marriage already splintering.

Meanwhile, on the road and in the studio, Ray's star rises. He signs with Atlantic Records, a label that understands Black music and gives him a degree of artistic freedom unusual for the time. In their studios, he cuts hits that redefine the sound of American popular music. The executives sometimes exploit him financially--standard practice in that era--but they also recognize his genius.

He builds a band, then a larger touring ensemble. By 1956, he hires a trio of female backup singers who quickly become known as The Raelettes. Among them is one extraordinary voice: Margie Hendrix (sometimes spelled Hendricks), fiery, bold, with a throaty tone that slices through any arrangement. When they rehearse, her energy crackles. Ray hears in her something that matches his own intensity.

He is already having an affair with another singer, Mary Anne Fisher, who wants a solo and dreams of a bigger place in his life. But as soon as Margie steps to the microphone, the emotional geometry changes. Her chemistry with Ray is instant and dangerous. They flirt with their phrasing in songs, trading lines, their bodies leaned toward each other over the piano.

On the bus and in motel rooms, Ray and Margie move from musical partnership to sexual affair. They are both married to other lives--Ray to Della, Margie with her own battles--but the road is a cocoon where rules feel bendable. Mary Anne, watching this shift, sees herself pushed to the side. When she discovers that Ray is now involved with Margie, jealousy and pain boil over. She cannot bear to be just another mistress. Mary Anne leaves the band, departing Ray's orbit entirely rather than stay in a triangle where her heart is breaking.

Della, at home, gives birth to Ray's child and tries to create a peaceful domestic space. Ray provides financially, buys her nice things, visits when he can, kisses the baby's head. But mostly, he is absent--physically on tour, emotionally numbed by heroin and the adoration of fans. Their marriage becomes a series of brief truces between long separations.

Professionally, though, Ray grows more powerful. His records sell. He negotiates better deals, insisting on control over his masters and a share of publishing--unprecedented demands for a Black artist in that era. On stage he is unstoppable, combining humor, sensuality, and virtuosic musicianship. He lets Black and white audiences dance together in front of the stage, ignoring local customs that demand segregation.

One night in Indianapolis, the crowd is mixed and wild, white and Black audience members swaying together, their bodies mingling where Jim Crow says they cannot. Authorities watch with fury. After the show, when Ray returns to his hotel room, police burst in, raiding the room. They search through his belongings and quickly find heroin.

He is arrested for heroin possession, the charge made loud and public. The newspapers seize on it, eager to tear down the rising star. Headlines scream about the blind musician and drugs. Della reads the stories, her stomach dropping.

His record label moves fast. In backroom maneuvering and legal finagling, they manage to have the charges dismissed. From the outside, it looks like a bullet dodged. But for Ray, it is one more notch in the long chain of addiction. Instead of reading it as a warning, he sees it as proof he can skate free.

The late 1950s and early 1960s are a blur of hits, tours, and scandals. Ray and Margie's affair deepens. She becomes pregnant with his child. The baby is born, and Ray now has another son out of wedlock, something he hides and half-acknowledges in the overlapping lives he's trying to manage. Margie drinks and uses drugs to dull the pain of being his secret. Della suspects other women, confronts him, and sometimes he denies, sometimes he simply shuts down.

Meanwhile, the country is shifting. The Civil Rights Movement is surging into the streets. Black people are demanding desegregation, voting rights, dignity under the law. Ray, an artist often wrapped in his own storms, cannot remain untouched.

In 1961, he travels to Augusta, Georgia for a concert. As his car pulls up, he hears chanting outside the venue. Civil rights protestors hold signs and shout about segregation. They explain that the concert hall is segregated: Black patrons are forced to stand in the balcony or behind a rope, while white patrons sit in the main seats.

The protestors plead with him: "Ray, don't play a segregated show. Don't help them keep this going."

Inside, the promoter reminds him of his contract, the money, the fans waiting. There is pressure from all sides. Ray stands there, blind eyes hidden behind his legendary shades, listening to the competing voices. A younger version of himself might have shrugged and gone on. But something in him refuses now.

He makes a choice. He steps to the line of protestors and tells the promoter he will not play in a segregated venue. "I'm not gonna perform where my people can't sit down front," he says bluntly.

The promoter threatens legal action. Georgia's officials bristle. The state retaliates with a drastic measure: they ban Ray Charles from performing in Georgia. For years, he is not allowed to play there, a punishment meant to make an example of him. It does, but in a different way--he becomes a symbol of resistance, an artist willing to give up money and exposure for principle.

Yet even as he refuses Jim Crow on stage, he cannot yet refuse the drugs in his veins or the women in his bed. His life splits into contradictions: a man of public courage and private surrender.

The Raelettes, led vocally by Margie Hendrix, keep touring with him, their harmonies growing tighter even as their personal lives fall apart. Backstage, the tension between Della's phone calls and Margie's demands grows unbearable.

At home, Della looks at their children and the empty chair at the table. When Ray does visit, she sees him nod off or disappear into the bathroom for too long, hears his slurred reassurances. Her patience cracks. She sometimes throws his drug kit at him, or refuses his touch in bed. Yet part of her still loves the man she married, the boy who once wanted only to play.

The film doesn't stamp dates on every event, but by the early 1960s, the strain is visible on everyone around Ray. Margie's drinking worsens; her voice grows more ragged. She knows she is one of many, yet cannot stop wanting more from him. When she becomes pregnant with his child and then finds herself raising their son with little emotional support, resentment seeps into every conversation.

At some point after the baby's birth, she and Ray have a brutal confrontation. She accuses him of using her and hiding her, of never intending to leave his wife. He oscillates between comfort and evasion, but offers no true resolution. It is another fracture he walks away from, returning to the road and the high.

Then comes the second major death that shadows his life: Margie Hendrix dies from a drug overdose. The film treats it as an off-screen blow, reported rather than witnessed, but the impact is seismic. Ray hears the news--Margie is gone, her body surrendered to the same world of drugs he swims in. Her death has no clear killer in the legal sense; it is the accumulation of addiction, despair, and the lifestyle that surrounded Ray. Her overdose is an indirect casualty of the choices Ray and their circle have made.

For Ray, it is like losing George all over again--another person he loved and failed to save. He cannot dismiss this one as background tragedy; Margie's voice is woven through his music, her laughter echoing in his memories. The guilt hits hard. Some part of him recognizes that heroin is not just hurting him, but killing the people around him. Still, even in that grief, the addiction clings.

Time moves on. The British Invasion and Motown are reshaping music, but Ray remains a towering figure. He experiments with country music, orchestral arrangements, and more, continuing to break genre boundaries. He negotiates record deals that give him unprecedented creative control and ownership of his master recordings, taking on the label executives and winning.

Yet each trip gets darker. When he flies back from a concert in Montreal in 1965, heroin is still his constant companion. He lands in the United States, weary but wired, and walks off the plane expecting another routine tour stop. Instead, he is met by law enforcement waiting at the airport.

They search his luggage. In his belongings, they find heroin again. There is no label to sweep this under the rug this time, no quick legal trick to make it disappear. The past arrest in Indianapolis, the increasing public concern over drugs, and Ray's own worsening habit all converge. He is arrested again in 1965 for heroin possession, this time facing serious federal charges.

News of the arrest reaches Della quickly. She has long since given up the illusion that things will just right themselves, but the shock still cuts. Their marriage has been tested relentlessly: by his affairs, the child he fathered with Margie, his long absences, and his addiction. But hearing that he may now face real prison time jolts something in her.

She visits him, or confronts him at home; the film shows her voice clear and resolute. She pleads, not as a meek wife but as a woman who has run out of tolerance. "Ray, you gotta stop," she tells him. "You're gonna lose everything. Your family. Your music. Your freedom. You're gonna die."

This time, the threat is real enough to reach him. In court, his lawyer fights fiercely, arguing that Ray is an addict in need of treatment, not a criminal to be locked away. They push for rehabilitation instead of incarceration. The judge, stern but perhaps moved by the argument and Ray's status, imposes a strict condition: probation in Boston, conditional on Ray completing a drug rehabilitation program and submitting to periodic drug tests.

He is sent to a rehab facility, a sterile, controlled environment utterly unlike the smoky clubs and hotel rooms he's used to. There, deprivation takes over. No heroin. No escape. His body revolts. The withdrawal scenes are brutal. He sweats, shakes, vomits. His skin crawls as if ants are beneath it. The pain is not just physical; it's as if every stored memory, every guilt, every vision of water and death rushes back at once.

In rehab he meets Dr. Hacker, a calm, analytical psychiatrist who runs the program and takes a personal interest in Ray's case. To engage his mind, Dr. Hacker teaches him chess, placing Ray's fingers on the board, describing each piece's moves. Strategy becomes a way to occupy his thoughts, to channel that restless intelligence into something other than craving.

One afternoon, Dr. Hacker explains to Ray how hard his lawyer fought in court, how the judge could easily have sentenced him to jail time. Instead, thanks to those arguments and the agreement struck, Ray is on probation in Boston, allowed to avoid prison only if he completes the rehabilitation program and submits to periodic drug testing. The terms are clear: relapse could cost him his freedom.

As his body detoxes, his mind explodes with vivid nightmares. These sequences are some of the most emotionally intense in the film. He dreams of water again, always water. He sees Georgia's washbasin, its surface like a dark mirror. He hears George's muffled thrashing, his brother's panicked breathing. He tries to move and is again that frozen child, unable to help.

Then the nightmare shifts. He sees his mother, Aretha, in the doorway, her face lined but strong. She speaks to him in that same unforgiving, saving tone. She reminds him of the promise he once made to her--to never be a cripple just because he's blind, to never surrender to weakness. In these visions she is both accusation and comfort, telling him that his real disability is not his lack of sight but his addiction, his refusal to face his guilt.

He also sees Margie, her voice echoing, her body slipping away into darkness, swallowed by the same drug he used to share with her. The ghosts of his past line up in his mind, each demanding acknowledgment. There is no heroin to quiet them now.

During one particularly harrowing withdrawal, he screams and thrashes in his bunk, sweat soaking the sheets, pleading for a fix. Orderlies and nurses restrain him. Dr. Hacker stands by, letting the storm pass, knowing that this agony is part of the process.

Somewhere inside that crucible of pain, something breaks--and then begins to heal. Ray starts to accept that heroin has been running his life, not the other way around. He realizes that each time he chose the needle, he stepped further away from the people who loved him and the music that defined him.

Slowly, day by day, the cravings lessen. His hands, so used to holding a syringe, rediscover the feeling of keys and pawns, of coffee cups and the edges of his own face. He starts to laugh again, to make jokes during chess games with Dr. Hacker. He talks more honestly about his past, about George, about his mother, about Margie. The rehab setting, stripped of glamour and applause, gives him nowhere to hide from himself.

After he completes the program, the court's conditions met, Ray emerges sober. It is not a magical cure; he will always carry the memory of heroin's pull. But something fundamental has changed. He chooses now--consciously--to put his family and health over heroin.

He returns home to Della Bea, not as the triumphant unbroken hero, but as a chastened man hoping for another chance. Their reunion is tentative. The wounds of years cannot be erased overnight. He admits his failures more openly, apologizes not with grand speeches but with a new consistency. He is present. He goes to bed straight instead of stumbling in high. He spends time with his children, learning their voices, touching their faces.

Over time, he reconciles with his wife. She watches him, skeptical at first, looking for signs of relapse. But as months pass and he remains clean, the ice thaws. There are still arguments, still scars, but now there is also a new trust, one earned in the crucible of rehab and humility.

Professionally, Ray enters a new chapter. His music keeps evolving. He tours again, but without the needle's constant shadow in his pocket. He can focus more sharply, hear the nuances, hang in the groove with clearer joy. Audiences respond not just to the songs but to the sense that he has walked through hell and come back.

Then, years after that fateful day in 1961, the state that once punished him reaches out. Georgia lifts its ban on Ray Charles, acknowledging that the old segregationist policies he opposed were wrong. State officials issue a public apology for the past, recognizing his stance against playing segregated venues as a courageous, principled act instead of the defiance they once condemned.

He is invited to perform in Georgia again, not as a cautionary tale but as an honored son. The film builds to this moment as both political and personal climax. The date is in the mid-1960s, after his rehabilitation--the exact year is not stamped on screen, but it follows his 1965 rehab and the subsequent ban's reversal.

The venue is grand, formal--a far cry from the juke joints and shoddy halls of his early career. Officials, dignitaries, and everyday fans fill the rows. Black and white sit together now, no balconies roped off, no seats segregated. The air hums with anticipation. People know the significance: Ray refused to bow to segregation, and now the state is bowing to him.

Backstage, Ray prepares. He is older, the lines on his face deeper, but there is a steadiness in his movements that wasn't there before rehab. No one hovers with a needle or a drink. He is surrounded instead by musicians, stagehands, and perhaps one or two quiet friends. His hands touch the piano lid, feeling its shape, grounding himself. He smiles a little--the wide, mischievous grin that always suggests he knows something the rest of us don't.

When he walks on stage, escorted only briefly and then left to stand at the microphone alone, the crowd rises in a standing ovation. He can't see them, but he feels the wave of sound, the rumble of stomping feet, the rush of clapping that seems to vibrate in his chest. He tilts his head back slightly, drinking it in.

A Georgia official speaks into the mic, voice formal. The state's representative publicly apologizes to Ray Charles Robinson, acknowledging the injustice of banning him for refusing to play a segregated concert. They praise his artistic contributions and his moral courage. They may even present him with a proclamation; the film emphasizes the dignity of the apology more than the legalese.

Ray steps to the microphone, says a few words--brief, humble. He does not gloat. He thanks them, perhaps with a wry suggestion that it took them long enough. His real response will be in the music.

He sits at the piano. The lights soften, the room quiets to a hush. His fingers rest on the keys. Then he begins to play "Georgia on My Mind."

The opening chords flow out, rich and resonant, each note a thread pulling history and hurt and healing together. His voice enters, that unmistakable grain and ache now tinged with hard-earned peace. He sings of Georgia as if it is a lover both lost and found, a place that once rejected him and is now returning him to the fold.

In the audience, people weep openly. For them, the song is no longer just a beautiful tune; it's a testimony of change. Black Georgians who once had to sit in balconies or were barred from shows entirely now sit front and center. White Georgians who grew up with segregation laws now watch a Black man they banned become a symbol of the state's better self.

As he sings, flashes of the past flicker through the film--George's small legs in the washbasin, Aretha's stern face, Marlene's exploitation, Oberon's whispered warning, Della's tears over his drug kit, Mary Anne's departure, Margie's laughter and then her overdose, the Indianapolis arrest, the 1961 Augusta protest, the Montreal flight and 1965 arrest, the rehab bed soaked with sweat, Dr. Hacker's chessboard. All of it funnels into this one performance.

There are no more deaths in the film after Margie's overdose and the long-ago drowning of George. Ray himself lives, sober and still creating, as the story ends in the mid-1960s. George Robinson died as a child by drowning in the washbasin, his death witnessed but not physically caused by Ray. Margie Hendrix died later from a drug overdose, a casualty of addiction in the orbit of Ray's world. Those are the only significant deaths the film depicts, and they remain like two bookends of guilt in his life--one from his childhood, one from his adult sins.

In this final scene, however, death is not the last word. Recovery is. As he reaches the climactic lines of "Georgia on My Mind," his voice swells, not with heroin's illusion of freedom but with genuine release. The audience rises again, applauding through tears. The camera lingers on his face--eyes closed behind dark glasses, mouth slightly open, sweat glistening at his temple.

He finishes the song, holds the last note just long enough, then lets his hands fall gently from the keys. For a moment there is silence--a held breath--then the room erupts. Standing, cheering, shouting his name: Ray Charles!

He smiles, a full, unguarded smile. Whatever he still carries--memories of water, ghosts of Margie, the dull throbbing knowledge that addiction is a lifelong fight--he carries as a sober man now, not as a prisoner of the next fix.

The film closes on that redemptive note, literally and metaphorically: a Black man who grew up in poverty in segregated Florida, lost his sight, lost his brother, lost himself in heroin and infidelity, now standing in front of a once-segregationist Southern state that has apologized to him, singing its name back to it with love and forgiveness.

Ray Charles Robinson walks off that stage alive, sober, and still creating, his story not ended but transformed.

What is the ending?

At the end of the movie "Ray," Ray Charles achieves great success and recognition for his music, but he also faces personal challenges, including his struggles with addiction and the impact of his past. He reconciles with his family and finds a sense of peace, ultimately performing a heartfelt tribute to his late brother, George.

In a more detailed narrative, the ending unfolds as follows:

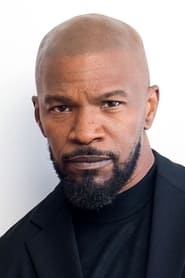

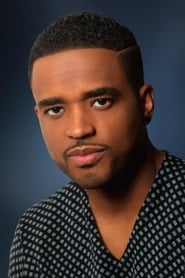

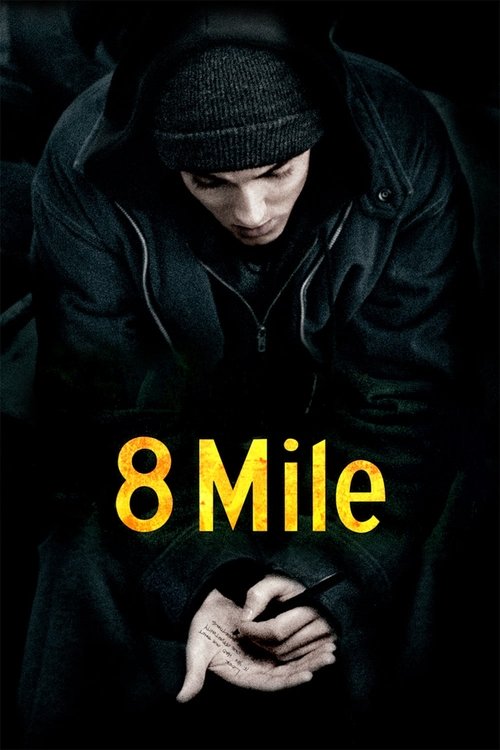

The film reaches its climax as Ray Charles, portrayed by Jamie Foxx, stands on stage at a concert, basking in the adoration of his audience. The lights dim, and the crowd erupts in applause, a testament to his hard-fought success. However, the journey to this moment has been fraught with personal demons and struggles.

As Ray prepares for his performance, flashbacks reveal the deep emotional scars from his childhood, particularly the tragic loss of his younger brother, George. This loss has haunted Ray throughout his life, shaping his character and driving his passion for music. The audience can sense the weight of these memories as he takes a moment to reflect before stepping into the spotlight.

In a poignant scene, Ray dedicates a song to George, channeling his grief and love into the performance. The music swells, and Ray's voice resonates with raw emotion, capturing the essence of his brother's memory. The audience is captivated, and tears flow as they witness the depth of Ray's connection to his past.

Meanwhile, Ray's relationships with his family and friends are also highlighted. His wife, Della Bea, played by Kerry Washington, stands by him despite his struggles with infidelity and addiction. Their bond is tested, but Della's unwavering support becomes a source of strength for Ray. In a moment of vulnerability, Ray acknowledges his mistakes and expresses his love for her, showcasing his growth as a person.

As the concert concludes, Ray is met with thunderous applause, a symbol of his triumph over adversity. However, the film does not shy away from the reality of his ongoing battle with addiction. In the final scenes, Ray is seen attending a support group, indicating his commitment to overcoming his struggles. This moment serves as a reminder that while he has achieved fame and success, the journey of self-discovery and healing continues.

The film closes with a montage of Ray's life, showcasing his impact on music and culture. His legacy is cemented as one of the greatest musicians of all time, but the audience is left with a sense of the complexity of his character--an artist who has faced immense challenges yet continues to strive for redemption and connection with those he loves.

In summary, the ending of "Ray" encapsulates the duality of Ray Charles's life: the celebration of his musical genius and the acknowledgment of his personal battles. Each character, from Ray to Della Bea, is left with a sense of hope and resilience, illustrating the enduring power of love and music in the face of adversity.

Is there a post-credit scene?

The movie "Ray," produced in 2004, does not have a post-credit scene. The film concludes with a powerful and emotional ending that encapsulates the life and legacy of Ray Charles. After the final credits roll, there are no additional scenes or content that follow. The focus remains on the narrative of Ray Charles' journey, his struggles, triumphs, and the impact of his music, leaving the audience with a sense of closure regarding his story.

What challenges did Ray Charles face in his early life that shaped his music career?

Ray Charles faced numerous challenges in his early life, including the tragic loss of his younger brother, George, who drowned when Ray was just five years old. This event deeply affected him and contributed to his emotional struggles. Additionally, Ray lost his sight at the age of seven due to glaucoma, which forced him to navigate a world without vision. Growing up in a poor neighborhood in Florida, he experienced racial discrimination and poverty, which fueled his determination to succeed in music despite the odds stacked against him.

How did Ray Charles' relationship with his mother influence his life and career?

Ray Charles had a complex relationship with his mother, Aretha. She was a strong influence in his life, instilling in him a sense of resilience and independence. After his father's abandonment, she worked hard to provide for Ray and his brother, but she also struggled with her own challenges. When she sent Ray to a school for the blind, it was a pivotal moment that allowed him to develop his musical talents. Her eventual passing left a profound impact on him, driving him to honor her memory through his music.

What role did addiction play in Ray Charles' life and how did it affect his relationships?

Addiction played a significant role in Ray Charles' life, particularly his struggle with heroin. His addiction began in the 1960s, and it created a rift between him and his family, especially with his wife, Della. The film portrays his battle with addiction as a source of shame and a destructive force that jeopardized his career and personal relationships. Despite his immense talent, Ray's addiction led to moments of crisis, including a near-fatal overdose, which ultimately forced him to confront his demons and seek help.

How did Ray Charles' musical style evolve throughout the film?

Throughout the film, Ray Charles' musical style evolves significantly, reflecting his personal growth and the influences around him. Initially rooted in gospel music, his sound begins to incorporate elements of rhythm and blues, jazz, and country. His innovative approach to blending these genres leads to the creation of what is now known as soul music. Key moments in the film showcase his experimentation with different sounds, such as the incorporation of orchestral arrangements and his unique piano playing, which ultimately revolutionizes the music industry.

What impact did Ray Charles have on the music industry as depicted in the film?

The film illustrates Ray Charles' profound impact on the music industry, showcasing how he broke racial barriers and changed the landscape of popular music. His ability to blend different genres not only appealed to a wide audience but also paved the way for future artists. The film highlights key performances and recordings that solidified his status as a pioneer, such as his hit 'I Got a Woman,' which is depicted as a turning point in his career. Ray's influence is shown to extend beyond his own success, inspiring countless musicians and contributing to the civil rights movement through his music.

Is this family friendly?

The movie "Ray," produced in 2004, is a biographical drama that chronicles the life of the legendary musician Ray Charles. While it is a powerful and inspiring story, it does contain several elements that may not be suitable for children or sensitive viewers. Here are some potentially objectionable or upsetting aspects:

-

Substance Abuse: The film depicts Ray Charles's struggles with addiction to heroin, including scenes of drug use and the impact it has on his life and relationships.

-

Sexual Content: There are scenes that involve sexual relationships, including infidelity and the portrayal of Ray's romantic encounters, which may be inappropriate for younger audiences.

-

Violence and Conflict: The film includes moments of emotional and physical conflict, including scenes that depict the harsh realities of racism and discrimination that Ray faced throughout his life.

-

Death and Loss: Themes of loss, including the death of family members and the emotional toll it takes on Ray, are explored, which may be distressing for some viewers.

-

Emotional Struggles: Ray's journey includes significant emotional turmoil, including feelings of isolation, depression, and the challenges of overcoming personal demons, which may be heavy for sensitive viewers.

Overall, while "Ray" is a compelling portrayal of a musical icon, its mature themes and content may not be suitable for all audiences, particularly children.