Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

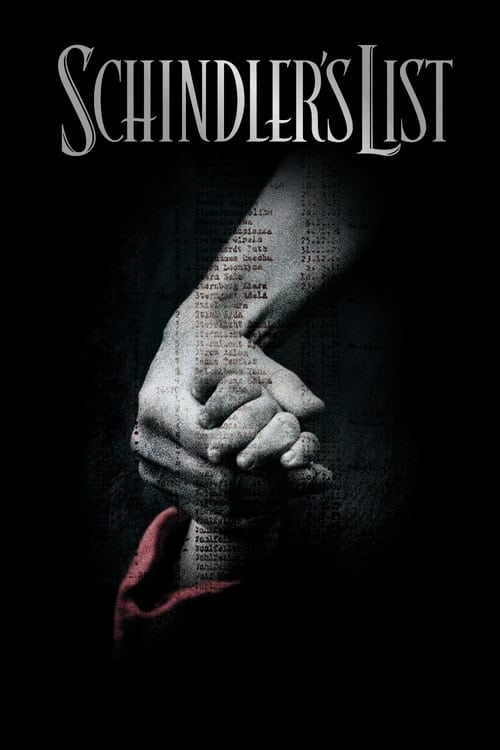

Flames flicker in the dark, small Shabbat candles glowing warmly on a family table. Hebrew prayers murmur over them, a fragile island of peace. Then the candles burn down, the frame drains of color, and the world shifts to stark black and white. It is Kraków, Poland, 1939, newly occupied by Nazi Germany. Jews stand in long lines under the eyes of Polizei and Wehrmacht, registering their names, occupations, and addresses. Stamp after stamp falls on papers that will strip them of property and freedom and force them into the Kraków Ghetto.

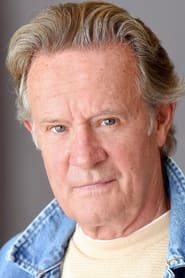

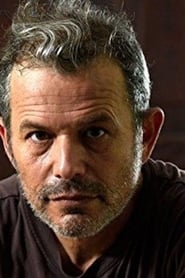

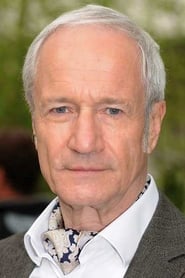

Into this rising machinery of persecution glides Oskar Schindler, impeccably dressed, tall and confident, an ethnic German from Moravia and a member of the Nazi Party. He arrives in Kraków intending to make a fortune off the war. At night, in a swank restaurant full of German officers, he spends freely. He orders cases of wine, fine food, and sends bottles to tables where Wehrmacht and SS officers sit. He moves among them with easy charm, pinning his Golden Party Badge to his lapel, taking mental notes: who likes attention, who likes gifts, who can be bought. He poses for photographs with them, always at their side, building an image: Oskar Schindler, loyal Party man, friend of the Reich.

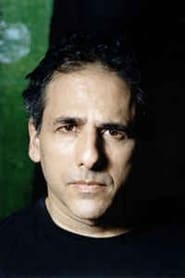

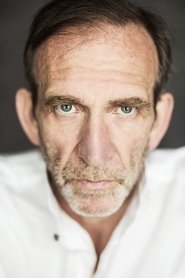

By day, Jews are herded into the newly created Kraków Ghetto, walled in and overcrowded. Families drag trunks and furniture through icy streets, past Polish civilians watching silently. Soldiers shout, children cry, an old man stumbles and is struck with a rifle butt. Among the Jewish community is accountant Itzhak Stern, quiet, bespectacled, working with what remains of Jewish business leaders and the Judenrat. Stern understands numbers and documents, but he also understands that paperwork now means life or death.

In a bare office, Oskar Schindler meets Itzhak Stern for the first time. Schindler wants a factory--specifically, a confiscated Jewish enamelware plant producing pots and mess kits for the German army. He needs Jewish contacts to arrange financing and operations, because Aryan capital is scarce and Jewish property is being seized. Stern sits behind a desk, skeptical, listening as Schindler boasts about the opportunity and the war contracts he will secure.

"Look, all you need is this," Schindler says, placing his Golden Party Badge on the desk. "The presentation." He leans in. "I know the right people, I do the entertaining, I make the deals. You, you do the books. You'll have your own office, your people will have work. We both get what we want." Stern agrees to help, but his face remains guarded. He knows work can mean protection, and he files that calculation away.

The Deutsche Emailwarenfabrik--DEF--comes alive. Machines whine, presses slam, enamel-coated pots roll off lines. At first, Schindler hires Poles. But Stern quietly points out that Jewish labor is cheaper--paid to the SS, not to the workers--and that employing Jews can also keep them from being sent away. Schindler, thinking of profit, agrees. Soon the factory floor fills with Jewish workers from the ghetto, their papers stamped "essential." To the German authorities, DEF is a valuable war factory; to the Jews, it is already becoming a shield.

Schindler lives well. He has an upscale apartment in Kraków, expensive suits, a glamorous German mistress besides his wife, Emilie Schindler, who visits occasionally. He drinks late at clubs with SS officers and businessmen, slapping backs, making crude jokes, sliding envelopes of cash across tables. His motives are simple: money, influence, pleasure. When Stern tries to bring him cases of specific Jews in need of jobs--a one-armed man, a learned rabbi--Schindler complains about inefficiency, about "nonessential" labor, but often relents, shrugging. It costs him little.

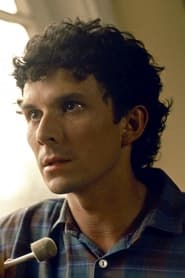

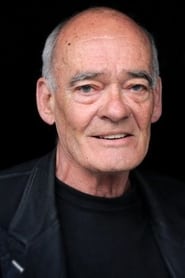

Outside the factory walls, the Nazi grip tightens. SS-Untersturmführer Amon Göth, later an SS-Hauptsturmführer, arrives to oversee the construction of a new labor camp: Płaszów, built on a Jewish cemetery on the outskirts of Kraków. He is young, broad-shouldered, his face alternating between boyish charm and dead-eyed cruelty. He surveys the cemetery and orders the tombstones pulled up to be used as paving stones for the road. Even the dead will not be allowed to rest.

When Płaszów is ready, orders come: the Kraków Ghetto is to be liquidated. It is March 1943. At dawn, trucks and armored cars roll into the ghetto. Loudspeakers blare instructions. SS men and Ukrainian auxiliaries fan out into the streets, kicking in doors. Jews are forced from their homes, lined up, sorted. Those deemed fit for work are marched toward Płaszów. The elderly, the sick, the very young--many are shot where they stand.

From a hill overlooking the ghetto, Oskar Schindler watches the operation on horseback. The scene below is chaos and slaughter: a woman shot on a stairwell, a man dragged away as he clutches a suitcase, a doctor trying to calm patients before Nazis storm in. Amid this monochrome nightmare, one figure stands out: a little girl in a red coat, the only color in the frame. She wanders alone, unnoticed, weaving between soldiers and bodies, looking for refuge. She crawls under a bed as gunshots echo. Schindler's gaze locks on her bright coat. Hours later, he sees a cart hauling corpses toward Płaszów. Among the piled bodies lies the same girl, red coat limp, tiny legs dangling.

Something cracks inside him. The war, the profits, the jokes about cheap Jewish labor--their meaning shifts. This is not merely a profitable opportunity; it is organized, deliberate extermination.

At Płaszów, Amon Göth steps out onto the balcony of his villa, which sits on a hill above the camp. Below him, thousands of Jewish prisoners stand in roll call, rows of shaved heads and striped uniforms. Göth, in a robe, lights a cigarette, lifts a rifle, and casually scans the camp as if it were a shooting gallery. He picks out a prisoner who seems to be resting or not working hard enough, aims, fires. The man drops. Göth calls to his orderly to fetch more ammunition. Each morning, each evening, he repeats this ritual of random executions. Prisoners drop for stumbling, for breaking a tool, for nothing at all. Göth becomes the living embodiment of arbitrary, sadistic power, and his bullets are everywhere: he kills men, women, unnamed prisoners whose only "cause" of death is his whim.

Among the prisoners is Helen Hirsch, his Jewish maid, living in a small room below the villa. She serves him, cleans his clothes, endures his presence. Göth oscillates between lust and hatred toward her. He pulls her into conversations, demands she admit she is attracted to him, beats her when she resists. He strikes her, throws things, leaves her bloodied on the floor. He does not kill her, but the threat is constant in every slap, every hand on her throat.

Kraków's Jews now live or die at Płaszów. Many of Schindler's workers are forced to reside there, marched each day to DEF and back under guard. They live in terror of Göth's rifle, of selections, of random beatings. Schindler visits the camp regularly, drinking with Göth, bringing him cigarettes, gifts, praise. He laughs at Göth's stories, endures his casual talk of killing. Privately, he despises the man, but he cannot afford to show it. Göth has absolute power over his workers' lives.

One evening, Schindler sits with Göth on the villa balcony, looking down at the camp. Göth brags about his power: "I pardon you," he says later, mimicking mercy as yet another mode of control. Schindler, drinking beside him, tries a different line of talk. He speaks about true power, about the emperor who can kill anyone but chooses to pardon. "That's power," Schindler says, "when we have every justification to kill, and we don't." Göth listens, intrigued, tries to imagine himself merciful. Disturbingly, in one scene, he considers sparing a boy who cannot clean a bathtub properly. He tells the boy he pardons him, sends him away--and then, a moment later, shoots him in the back anyway. Göth's brief flirtation with mercy ends in murder.

Schindler's factory remains a relative haven. Inside DEF, SS guards are kept at the gates as much as possible. Stern, now Schindler's indispensable right hand, manages the roster. He understands that a name on the factory list can be the only barrier between a person and death. Quietly, he alters entries, adds relatives, slips in doctors, teachers, children under the guise of "skilled workers." Schindler notices and, increasingly, lets it happen.

But Schindler still walks a dangerous line. At a party in the factory, he kisses a Jewish worker on the lips in front of others. Word spreads. For this breach--race defilement--Schindler is arrested by the Gestapo. He is interrogated, detained. The film does not spell out the exact number or dates of each arrest, but he is seized more than once, his behavior scrutinized. Each time, he is released, thanks to connections and bribes, but the message is clear: he is under suspicion.

Göth's brutality escalates. In the camp yard, he executes a woman engineer who dares point out that his men are building barracks on faulty foundations. She is shot in the head in front of everyone, her body crumpling into the mud. In the background or in montage, other prisoners are killed: an old man who cannot shovel fast enough, a woman who runs, a crippled worker. Many of these victims are unnamed in the film, but their deaths are directly caused by Göth and his guards, often in cold blood, often as spectacles to terrorize the rest.

Schindler's attitude shifts from profit to protection. He begins to bribe Göth not only for contracts, but to obtain specific concessions: the right to build a sub-camp at his factory, where his workers can live under his control rather than Göth's. Over drinks, he hints at secret production, at the need for efficient workers, at the benefit of keeping them close. Göth names a price--massive, per head--and Schindler pays, again and again. He spends his earnings renting his workers from the SS, buying luxury items on the black market to placate officers and bureaucrats who might interfere. His enamelware profits begin to dissolve into bribes, food, medicine, and favors for his Jewish workers.

He also intervenes in individual cases. He notices Helen Hirsch's bruises and the permanent flinch in her eyes. One day he visits Göth and, during a drinking session, casually mentions he needs a maid. He offers to take Helen off Göth's hands, paying for her as a servant. Göth toys with the idea, taunting Helen, forcing her to admit she is afraid of him. He ultimately refuses to give her up fully, but Schindler's interest reveals his growing willingness to risk angering Göth to save a single life. Helen remains in danger, yet Schindler's protection--limited and indirect--contributes to the fact that she survives Göth's reign.

As the war drags on, the tide turns against Germany. The Red Army approaches from the east; Allied bombers strike German cities. Orders come down to dismantle camps and move prisoners deeper into the Reich, toward extermination centers like Auschwitz-Birkenau. Płaszów is to be closed. The Jews still there, including many of Schindler's workers, are slated for transport to Auschwitz. For most, that means death.

Schindler faces a choice: leave Kraków with his accumulated wealth, as he had once planned, or try to save his workers from the transports. He cannot simply keep them in Kraków; the Reich is collapsing, and the Final Solution is accelerating. He hatches a new plan. Near his hometown of Zwittau, in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, he proposes to build a new factory in Brünnlitz (Brněnec), producing artillery shells for the German army. It will be closer to the front, more efficient, he tells officials. He will need skilled workers--Jews he already employs and others he will "train."

He goes to Amon Göth with his plan. The conversation is a pivotal confrontation. Göth sits listening, skeptical, aware of the value of his slave labor. Schindler makes his pitch: he needs his workers transferred from Płaszów to Brünnlitz. Göth names his price: a bribe per worker, huge sums. Schindler agrees. The more he pays, the more names he can add. It is a straightforward transaction in Göth's mind: he sells Jews to Schindler as commodities.

In a dimly lit office, Itzhak Stern sits at a typewriter and begins to compile names. The clack of keys is urgent, rhythmic. Men, women, children, families--they are listed as fitters, machinists, metalworkers, whatever will justify their inclusion. Schindler stands over him, dictating some names, approving others, deferring frequently to Stern's knowledge of who is most at risk. The list grows: about 1,100 Jews. Here the film focuses more on the significance than exact numbers; historically it is roughly 1,100–1,200.

"This list… is an absolute good," Stern says quietly. "The list is life. All around its margins lies the gulf." It is the closest thing the film has to naming its central object: a simple typed document that means survival.

Not everyone can be included. Some workers who had been at DEF are left off because there is not enough money or space; others cannot be found. The absence of their names is a silent death sentence. The film does not detail each of their fates, but the context is clear: Jews not on the list are shipped to Auschwitz or other camps and, in many cases, killed.

The transports begin. At Płaszów, men are separated from women, children from parents. The men's list, around 800, travels directly to Brünnlitz; the women and children, several hundred, are supposed to follow. On the railway platforms, in the smoke and whistle of departing trains, SS guards shout, shove, beat. The men on the list board cattle cars marked with their destination. They are frightened but have papers naming Brünnlitz and Schindler's factory. The doors slam shut; a metal bar locks them in.

The women's train, however, does not go to Brünnlitz. Through administrative malice or "error," it is diverted to Auschwitz-Birkenau, the extermination camp in occupied Poland. The train screeches to a halt under the infamous gate. Women and girls spill out into a sea of confusion, watched by SS guards and kapos. They are herded into lines, processed. Their heads are shaved, their clothes stripped away, their belongings taken. Numbers are tattooed on their arms in some cases, though the film focuses more on the terror in their eyes than on the ink.

The women, including many of "Schindler's women," are marched, naked and shivering, toward a concrete building. Chimneys billow smoke in the distance. They are pushed into a large chamber with showerheads in the ceiling. The heavy door slams shut. They huddle together, crying, praying, convinced they are about to die. The camera lingers on their faces: some whisper the Shema, some scream, some go silent. A hiss begins. But instead of Zyklon B gas, water sprays down on them. In this moment, the film shows the unimaginable: a room configured for mass murder used, almost mockingly, as a shower. The women laugh and sob hysterically, alive but still trapped in Auschwitz, still inches from death.

Back in Kraków and then in Brünnlitz, Schindler learns that the women's transport has gone to Auschwitz. He does not hesitate. He travels there, carrying money and luxury goods. He meets with camp officials, joining them in an office full of ledgers and maps. When bribes alone are not enough, he resorts to flattery, to the language of production: these women are essential; he has already paid for them; the Reich needs their labor. Slowly, grudgingly, the Auschwitz bureaucracy accedes. The women are pulled out of the system, loaded back into cattle cars, and sent on to Brünnlitz.

On arrival at Brünnlitz, the men and women are reunited. They are emaciated, traumatized, but alive. Schindler has bought them back from the machinery of annihilation. He now has his full workforce.

The new factory at Brünnlitz stands among the hills of Bohemia, cold and stark. Barracks rise nearby. SS guards patrol the perimeter, but Schindler negotiates strict limits on their presence inside the plant. He forbids them from entering the production floor, from harassing his workers. The Jews sleep in on-site barracks rather than being marched back and forth to another camp. Rations are meager, but Schindler supplements them from the black market when he can. On at least one occasion, he allows the workers to observe the Sabbath, halting production, an act that, if discovered, could be seen as sabotage of the war effort.

Officially, Brünnlitz is a munitions factory, tasked with producing artillery shells. In reality, Schindler ensures that not a single usable round leaves the plant. Machines are calibrated just slightly off; measurements are wrong; primers fail. Over seven months, he spends his remaining fortune bribing officials and buying finished shell casings from other factories so he can ship something while secretly keeping his own production line effectively nonfunctional. When test-firing their shells, they always "fail." For the German army, Schindler's factory becomes a drain; for his workers, it is a sanctuary.

By early 1945, Schindler is financially ruined. He has poured his wealth into bribes, food, medicine, and false production. The war, too, is nearing its end. In Europe, Germany's surrender comes in May 1945; on May 8, Victory in Europe Day is declared. In Brünnlitz, tension builds during these final weeks. The front lines are collapsing; rumors of "no survivors" orders circulate through camps. Schindler fears that, as the SS retreats, they will carry out one last massacre, killing all the Jews in his factory to erase evidence.

He quietly arms some of the workers, slipping them weapons, instructing them to be ready, though he knows that in open conflict the SS would likely slaughter them. At night, he and Stern stand in the factory, listening for distant artillery, wondering how much longer they can hold out.

At last, word comes: Germany has surrendered. The Third Reich is finished. For Oskar Schindler, this is both relief and danger. He is a Nazi Party member, a self-described "profiteer of slave labor," an industrialist who has used Jewish labor and enriched himself--even though he later spent it all to save them. The advancing Soviet Army considers men like him war criminals until proven otherwise. He cannot stay.

Before he goes, there is one more confrontation. At night, he gathers the SS guards stationed at Brünnlitz in the factory hall. The Jewish workers stand apart, watching, tense. The guards are armed, uncertain, aware that orders elsewhere have called for extermination of prisoners to hide crimes. Schindler faces them, not as a jovial host now, but as someone who has staked his soul on these people.

He tells them that the war is over, that they have a choice. The specifics of his speech vary slightly among accounts, but in the film he appeals to their self-preservation and to a sliver of conscience. He urges them to walk away, to return to their families "as men, not as murderers." The silence stretches. The guards look at one another, at the Jews, at the floor. Then, one by one, they turn and walk out. They do not open fire. They do not obey the implicit expectation of a final massacre. They simply leave, their boots echoing in the factory as they vanish into the night.

Schindler then turns to the assembled workers. It is time to say goodbye. He and his wife Emilie, who has stayed with him through Brünnlitz and helped care for the camp, must flee west, trying to reach American lines and avoid Soviet arrest. The workers, led by Stern, step forward with a document. It is a signed statement, written on factory paper, attesting that Oskar Schindler has saved Jewish lives, that he has treated them humanely, that he is not like other Nazi profiteers. If he is captured, he can show this to his captors.

Stern also presents a ring. The gold for it has been melted down from a worker's dental bridge. Inside is engraved a paraphrase from the Talmud: "Whoever saves one life saves the world entire." Schindler reads it, his face crumpling. He realizes that all he has done--the bribes, the lies, the sabotage--has been seen, remembered.

And then the weight of what he did not do crashes down on him. He looks at his car, at his Golden Party Badge, at his fine coat. "I could have got more," he says, voice breaking. "I could have got more." He points to the car: "This car--ten people, right there." To the badge: "This pin, two people. One more person. And I didn't… I didn't." He sobs, overwhelmed by guilt for those he did not save, for the millions beyond his list, for every empty line where another name might have been. The workers surround him, Stern holding him as he weeps. They insist that he has done enough, more than anyone could expect, that thanks to him they are alive.

That night, dressed not in his usual finery but in worn clothes resembling those of Polish prisoners, Oskar and Emilie Schindler climb into their car and drive off into the darkness, posing as refugees, heading west toward American forces. They leave their workers behind, the factory now silent.

Morning comes. The Jews of Brünnlitz wake in their barracks. There are no guards, no roll call, no barking orders. They slowly emerge into the yard, uncertain. Then a mounted Soviet officer appears on horseback at the camp gate. He looks at them, these hollow-eyed survivors surrounded by smokestacks and barbed wire. He announces that they have been liberated, that the war is over. When they ask where they should go, he replies bluntly that they should not go east: "They hate you there," he says--an acknowledgment of ongoing antisemitism even beyond Nazi rule. And west? He shrugs; he cannot say. The future is unknown.

The prisoners stand in the empty yard, free yet rootless. Then they begin to move, slowly at first, then in small groups, walking out of the camp and into the open countryside. The camera watches them go, spreading across the fields, their figures small against the vast landscape, moving toward a life that must be rebuilt from ashes.

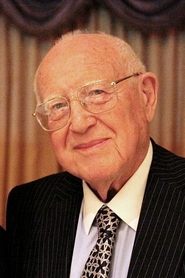

The black-and-white image fades, and color returns. Years have passed. Now the film shifts from drama to epilogue. One by one, real-life survivors--the Schindlerjuden--walk onscreen, accompanied by the actors who portrayed them. They are older now, living in Israel. Together, pairs of survivor and actor approach a grave in Jerusalem: the resting place of Oskar Schindler.

Each survivor places a small stone on the gravestone, following Jewish tradition--a mark of visit, respect, enduring memory. The stones pile up, a new kind of list, each rock representing a life that continued because one man chose to spend his fortune and risk his life for others.

Text on the screen explains that Oskar Schindler saved more than 1,100 Jews during the Holocaust, and that their descendants now number in the thousands, while in contrast, there are comparatively few descendants of Nazis in Germany and Poland. The camera lingers on the grave, covered in stones, and finally on a single figure walking away.

The story ends knowing exactly who lives and who dies--knowing that many unnamed Jews in the Kraków Ghetto, in Płaszów, and on transports to Auschwitz are killed by bullets, by starvation, by gas, often at the hands of Amon Göth and his SS men; knowing that Helen Hirsch survives Göth's abuse and leaves the war alive; knowing that Itzhak Stern survives and stands at the grave in the epilogue; knowing that Oskar Schindler himself dies years later and is buried in Jerusalem, honored by those he saved. The film holds nothing back: the ghetto liquidation, the girl in the red coat whose corpse is hauled away, the women nearly gassed in Auschwitz, the endless shootings from Göth's balcony, the countless faceless deaths that surround a single list of 1,100 names.

And so the last image is not of Schindler the playboy in a nightclub or Schindler the factory owner on a balcony, but of a grave covered in stones, each stone a silent testimony that, in the midst of systematic murder, one man chose to turn a list of workers into a list of the living.

What is the ending?

At the end of "Schindler's List," Oskar Schindler, a German businessman, reflects on his actions during the Holocaust and the lives he saved. He is filled with regret for not saving more Jews. After the war, he is honored by those he saved, but he is left with a sense of loss and sorrow. The film concludes with a powerful scene where the survivors and their descendants visit Schindler's grave, placing stones on it as a sign of respect.

In a more detailed narrative, the ending unfolds as follows:

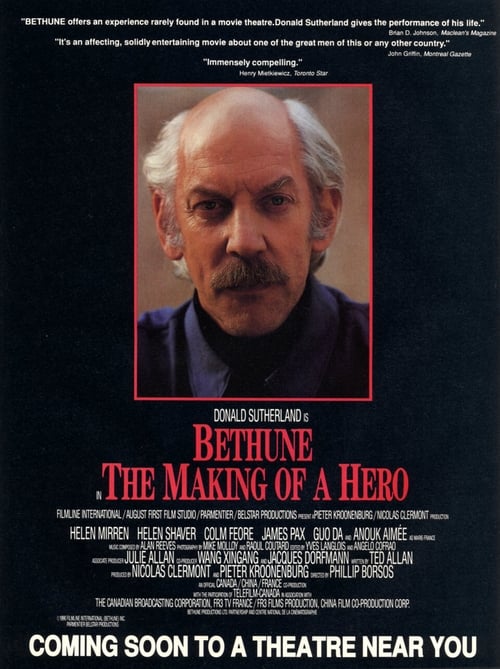

As the war comes to a close, the Jewish workers in Oskar Schindler's factory are liberated. The scene is somber yet filled with a sense of relief. Schindler, played by Liam Neeson, stands before his workers, who have become more than just employees; they are now a family forged through shared suffering and survival. The atmosphere is heavy with the weight of what they have endured, and Schindler's expression reflects a mix of pride and deep sorrow.

In the final moments of the film, Schindler is confronted with the reality of his actions. He is surrounded by the people he saved, yet he is haunted by the thought of those he could not save. He looks at the gold watch he has worn, a symbol of his wealth and success, and realizes that it could have saved more lives. His internal conflict is palpable; he grapples with feelings of guilt and regret, wishing he could have done more. He exclaims, "I could have gotten more," as he reflects on the lives that were lost and the potential he had to save them.

The scene shifts to the aftermath of the war. Schindler is forced to flee as the Nazis lose power, and he is seen packing his belongings. His Jewish workers present him with a letter of gratitude, acknowledging his bravery and the lives he saved. They express their deep appreciation, but Schindler's face is etched with sorrow. He knows that the war has left scars that cannot be healed, and he feels the weight of the lives he could not save.

As he departs, the film transitions to a poignant scene at Schindler's grave. Years later, the survivors and their descendants gather to honor him. They place stones on his grave, a Jewish tradition symbolizing remembrance. The camera pans over the faces of those he saved, now living their lives, a testament to the impact of his actions. The emotional weight of the moment is profound, as the audience sees the legacy of Schindler's choices reflected in the lives of those who survived.

The film concludes with a powerful visual: the survivors walking together, hand in hand, as they pay tribute to the man who risked everything to save them. The final shot is a haunting reminder of the past, juxtaposed with the hope of the future, as the camera captures the faces of the living, forever changed by the horrors they endured and the man who chose to stand against them.

In summary, the fates of the main characters are intertwined with the themes of sacrifice, regret, and the enduring impact of one man's choices. Oskar Schindler, despite his flaws, emerges as a complex figure whose actions saved over a thousand lives, while the survivors carry forward the memory of those lost, ensuring that their stories are never forgotten.

Is there a post-credit scene?

"Schindler's List," produced in 1993, does not have a post-credit scene. The film concludes with a powerful and poignant ending that encapsulates the themes of sacrifice, humanity, and the impact of one man's actions during the Holocaust. After the main narrative, the film transitions into a somber sequence where the real-life survivors and descendants of those saved by Oskar Schindler pay tribute to him at his grave in Israel. This scene serves as a reflective moment, emphasizing the lasting legacy of Schindler's bravery and the lives he saved, rather than providing any additional narrative content or resolution. The film ends on a note of remembrance and honor, leaving the audience with a profound sense of the historical significance of the events depicted.

What motivates Oskar Schindler to save Jewish lives during the Holocaust?

Initially, Oskar Schindler is portrayed as a profit-driven businessman who seeks to exploit the war for his own gain. However, as he witnesses the brutal treatment of the Jewish people and the atrocities committed by the Nazis, his motivations begin to shift. The turning point comes when he sees the horrific conditions in the Plaszow labor camp and the execution of his Jewish workers. This emotional awakening leads him to use his factory as a refuge for Jews, ultimately prioritizing their lives over his financial interests.

How does Amon Goeth's character represent the brutality of the Nazi regime?

Amon Goeth, the commandant of the Plaszow labor camp, embodies the sadistic and dehumanizing nature of the Nazi regime. His character is marked by a chilling detachment from the suffering of his victims, often taking pleasure in the act of killing. Scenes depict him shooting Jews from his balcony for sport, showcasing his moral depravity. Goeth's interactions with Schindler reveal a complex dynamic, as he admires Schindler's wealth but remains oblivious to the value of human life, representing the extreme cruelty and moral corruption of the time.

What role does Itzhak Stern play in Schindler's transformation?

Itzhak Stern, Schindler's Jewish accountant, plays a crucial role in Schindler's moral awakening. Initially, he assists Schindler in managing the factory and its Jewish workers, but as the situation for Jews worsens, he becomes a key figure in helping Schindler understand the gravity of their plight. Stern's intelligence and resourcefulness help Schindler compile a list of workers to save, and his unwavering commitment to his people deeply influences Schindler's actions. Their relationship evolves from a business partnership to a profound bond, highlighting the impact of personal connections in times of crisis.

What is the significance of the list that Schindler creates?

The list that Schindler creates is a powerful symbol of hope and salvation amidst the horrors of the Holocaust. It represents not only the lives he is able to save but also the moral choice he makes to protect those who are being persecuted. Each name on the list signifies a life spared from certain death, and the act of compiling it becomes a desperate yet determined effort to resist the dehumanization of the Jewish people. The list ultimately serves as a testament to Schindler's transformation from a self-serving businessman to a savior, illustrating the profound impact one individual can have in the face of overwhelming evil.

How does the film depict the relationship between Schindler and the Jewish workers?

The relationship between Schindler and the Jewish workers evolves significantly throughout the film. Initially, Schindler views them primarily as a means to profit from the war, but as he witnesses their suffering and the brutality of the Nazis, he begins to see them as individuals with lives, families, and hopes. This shift is illustrated through various scenes where he interacts with his workers, showing moments of compassion and camaraderie. The emotional weight of their plight becomes increasingly apparent to him, culminating in his desperate efforts to save as many lives as possible, which fosters a deep sense of loyalty and gratitude among the workers towards Schindler.

Is this family friendly?

"Schindler's List," directed by Steven Spielberg, is a powerful and harrowing film that deals with the Holocaust and the atrocities committed during World War II. It is not considered family-friendly due to its intense and graphic content. Here are some potentially objectionable or upsetting aspects that may affect children or sensitive viewers:

-

Graphic Violence: The film contains several scenes depicting brutal violence, including shootings, beatings, and the execution of Jewish people by Nazi soldiers.

-

Depictions of Death: There are numerous scenes showing mass graves, corpses, and the aftermath of violence, which can be very distressing.

-

Emotional Trauma: Characters experience profound loss, fear, and despair, which may be difficult for younger viewers to process.

-

Concentration Camps: The portrayal of life in concentration camps is stark and disturbing, showcasing the inhumane conditions and treatment of prisoners.

-

Racial and Ethnic Persecution: The film addresses themes of anti-Semitism and the systematic extermination of Jews, which may be upsetting for some viewers.

-

Child Endangerment: There are scenes involving children in perilous situations, which can be particularly distressing.

Due to these elements, "Schindler's List" is generally recommended for mature audiences and is often rated R for its content. Viewer discretion is strongly advised.