Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

Friuli, autumn 1917. A low, cold light falls over the broad courtyard of a family villa near Palmanova where Marcello Giammarco lives; he moves through marble halls and long corridors that have been half-emptied for the war. Soldiers and stretcher-bearers pass in the driveway. In the rooms that face the fields, hospital cots line up beneath chandeliers. Nurses in rough uniforms bend over wounds, while porters and house servants obey orders with the same mechanical competence they once reserved for silverware. Marcello, a dwarf and the only son of a prosperous lawyer, walks carefully between beds and brass rails, adjusting a blanket here, placing a basin there, speaking quietly to men whose faces are slack with fever. He keeps the manners his class taught him: courteous, measured, distant. He eats at the servants' table when the staff permit, speaks to the doctor when requested, and retreats to the library to smoke cigarettes and read legal briefs left by his father.

Outside the villa, the countryside smells of earth and smoke. The front line has pushed and been pushed; the villa sits in the Italian rear but close enough that every distant rumble makes the chandeliers tremble. Marcello spends afternoons watching the brothel in town, looking for Maria. She is a prostitute who works for the local house of ill repute; Marcello has been trying to establish a relationship with her, sending small gifts, lingering with his eyes when she passes by the gate. He speaks to her when he can, attempting to reduce the formal distance between them into something warmer. Maria answers with guarded affection: she accepts his candies, she brushes his hand lightly at the market, she laughs at jokes he makes about books. She tells him nothing of her fears about the approaching enemy.

The war presses in. In late October, the chain of events that the men call Caporetto begins to unfold. The Austro-German offensive breaks the Italian line. Reports arrive at the villa in clusters: radioed orders, breathless messengers, an officer with mud on his boots. The father, a lawyer and the family's head, goes out to the garden to look toward Palmanova. He stands on the terrace as artillery booms in the distance. Marcello watches him from an open window, clutching the balustrade; he cannot imagine the future without his father, he cannot imagine taking responsibility for the household, but he keeps watching because one smallness of movement might be a help: to summon aid, to hold a cloak. A shell, fired as the town falls and the lines convulse, lands near the villa. It strikes his father's body with a single, catastrophic impact. The father dies where he stands, hit by shrapnel and blown into the gravel. His death is immediate; surgeons cannot save him. Marcello runs out into the mud and winter wind and finds his father's face already still. Soldiers carry the body back inside. The villa fills with a new, quieter kind of bustle: legal papers are gathered, a will is produced and read aloud, and Marcello is told that he is now the heir, that the estate belongs to him.

With his father's death Marcello inherits the property, the title deeds, the money. He is young, physically small, unused to command. He remains in the villa as the world outside collapses and reorganizes. Soon an Austrian rear command moves into the familiar rooms. Officers in decorated uniforms set up a map table in the drawing room. They requisition rooms for their staff, establish a radio in the library, and place sentries at the gate. Marcello continues living there, tolerated by the occupying force. He is allowed to remain because the Austrians value the villa's facilities and because local administrators prefer a stable face in charge of accounts and servants. The presence of the enemy becomes an odd domesticity: Marcello wakes to the bugle's call, shares the billiard room with a captain, signs receipts handed to him by a lieutenant.

The brothel in town changes with the occupation. The clientele shifts from Italian regulars and civilians to Austrian soldiers with medals and extra pay. Maria works there under new constraints. Officers command rooms; they choose women as if they are parts of a festival. She takes Marcello's letters and sets them aside when officers look in. In the daytime she tries to avoid him; at night she is expected to attend to men who speak German and pay in crowns. Marcello tries to find her in the alleys, to speak gently, to ask her to leave with him to the safety of the villa, but she resists because leaving would mean contempt from her madam, and because Austrian money offers an immediate escape from hunger. He watches her through a window while soldiers laugh and pass goblets between them. When he sees her alone, he goes to the brothel and asks for a private moment; the madam allows it for a price. Inside, Maria and Marcello speak in whispers. He offers to marry her; she answers that marriage would ruin her livelihood and that any union now would be frowned upon by a world in which survival requires compromise. Their conversations swing between tenderness and practical negotiation: gifts, promises to wait, whispered plans to leave when the fighting ends. Marcello gives her money and promises the villa; Maria accepts the money and the platitudes, because each of them clings to what the other offers.

War shifts loyalties among the villagers and servants. A number of once-ignored families now see Marcello's inheritance as a lifeline. They gather in small groups at the market and in taverns, muttering that the Giammarco money should be redistributed, that those who sacrificed should be rewarded. A local profiteer, a shrewd man who has made his living through opportunism and barter, notices this murmuring. He reads the room as a man who understands hunger: his name is Giovanni, he handles transactions between farmers and officers, and he manages to keep his ledger open while others close theirs. Giovanni sees Marcello's status as a vulnerability. He begins to whisper suggestions, to cultivate the injured and the forgotten: a discharged sergeant whose farm was burned, a servant who feels passed over, a miller who has been refused credit. Giovanni meets them in the attic of a tavern, paying for drinks, promising that with Marcello's money they can reclaim what the war has taken. He tells them that the villa and the bank account are ripe for the taking, that Marcello's small body and gentle manner make him easy to manipulate. Giovanni lays plans that combine legal maneuvering and public pressure. He persuades someone to produce a claim that Marcello is incapable; he suggests a proxy to petition the courts under the confusion of war; he spreads rumour that the registrar in Palmanova will favor a petition if it carries the correct bribe.

Marcello senses the hostility around him but cannot name its source. He notices letters misdirected, receipts missing from files, and once finds a servant rifling through his father's papers. When he confronts the servant, the man looks at him without shame, saying the household must pay its debts. Marcello counters with small kindnesses: he gives a bonus to a nurse, he refuses to remove a servant who has been loyal. His gestures anger Giovanni; the profiteer interprets mercy as softness, and he begins to escalate his tactics. He plants forged documents that suggest an alternate will in which part of the estate is to be held in trust; he creates false accounts showing debts incurred to cover supplies for the troops. Marcello signs a receipt for a consignment of blankets that never arrives because he believes the paper to be accurate. These small manipulations grow into public accusations. At the market, someone shouts that Marcello is squandering property on the enemy; a group of men stand on the steps of the villa and chant, pressing their faces against the gate.

The Austrian command engineers a different pressure. An officer who has befriended Marcello says that with the front shifting, the Austrians will need solid local support; in return for cooperation, they will offer protection. Marcello, who has been sheltered and tolerated by the officers, refuses the idea of collaborating beyond the basic courtesies required to keep the villa functioning. He resists signing orders that would hand property or identify men who aided the Italians. The officer, who is courteous in appearance, makes it plain that coercion can be decisive: a few discreet threats will smooth the process. Marcello does not yield; he stands in the library and declines to give up his account books. The officer responds by posting a guard at the gate and assigning a corporal to assist with inventorying the property.

Giovanni moves his plan to greater boldness. He recruits the miller and the discharged sergeant to present a petition to the municipal commission. They claim Marcello's father died insolvent, that Marcello is not competent to manage the estate, and that the village has a right to assume temporary guardianship. Giovanni supplies forged financial statements and a letter supposedly from the notary that indicates the town's better use of the property. The commission, stretched thin by war and subject to both Italian administrative collapse and Austrian oversight, reluctantly agrees to investigate. The notary's office has been disrupted; records are lost, and the commission takes the petition as plausible. A hearing is set in the villa. Marcello receives a summons and sits in a room that has been stripped of its blinds. He thinks of his father and of Maria, who watches him from a distant doorway, and he prepares to defend his name.

At the hearing, Giovanni and the petitioners speak first. They show papers and witnesses who recount debts and failures. The Austrian officer translates and interjects with neutral tones. Marcello produces his own ledgers and calls servants who can verify payments. The officer asks probing questions and notes inconsistencies in both accounts. The hearing becomes a contest of wills. The commission decides to appoint a temporary administrator until the papers can be verified, and it names an outsider -- a retired magistrate from a neighboring town -- as conservator. Marcello is stunned. He protests and offers proof of solvency. The conservator orders the closing of certain accounts and the freezing of property transfers. Giovanni smiles thinly. The townsfolk interpret the order as a victory. Marcello is, officially, controlled.

Throughout these developments Marcello's relationship with Maria grows more complicated. She confesses to him in the quiet of a corridor that she accepted Austrian clients to feed her family and to pay a debt owed to the madam. Marcello replies that he understands survival and that he wants to help, but Maria says that help will cost her reputation and cost him certain disdain. One night, she sits with him in the villa's kitchen where the cook prepares simple stew. Maria tells him that she has been offered a position--a housekeeper's post in the Austrian command, proper and paid, far from the brothel. The offer comes with increased shelter and a promise of safety. Marcello asks her to stay with him in the villa as his companion; she answers that staying would mean scorn and no security. She does not explicitly refuse, but when the Austrian officer formally offers Maria the housekeeper post, she accepts. Marcello watches her leave the brothel with a basket and presents her with a small gold chain he has bought with his allowance. She touches the chain and holds him for a moment, pressing her forehead against his forehead as if to commit the warmth to memory; then she walks away with the officer. Marcello stands in the doorway until the last light slips behind the eaves.

As winter deepens, the conservator runs the estate's affairs with measured, bureaucratic hands. He inventories the household silver and determines which annuities must be paid. He resumes payments to creditors and arranges for the staff to receive wages, albeit reduced. Giovanni sees that legal victory eludes him for now but he does not abandon the plan: he keeps whispering to men in the tavern, he cultivates the conservator's clerks, and he prepares to contest every account that emerges. Marcello sits in the study and signs the forms the conservator demands. He learns to calculate, to record, to defend the remaining assets with his father's notes turned into a manual. He meets with the surgeon and the head nurse to ensure the wounded remain tended; the hospital wing continues to take in men sent from the front, many dying slowly of infection and cold. Marcello spends nights listening to the coughs and the low moans of men whose lungs fail, and in the morning he writes receipts for suppliers who bring bread and coal.

Then the front changes again and the political landscape shifts. Orders arrive that the Austrian command must pull back part of its staff to the east. Some officers pack their trunks and leave at dawn. The officer who once befriended Marcello thanks him politely and tells him that fortune has random turns; they clasp hands with a certain formalism. Maria remains as housekeeper with the remaining staff. The conservator arranges the villa's resumption into civilian hands once the military files clear. Giovanni senses opportunity in the fluidity: he recruits one of the conservator's clerks, a man in debt, and slips forged documents back into the ledger drawer. He submits a claim that Marcello has hired a foreign confederate to siphon funds and that Marcello's signature has been forged on important transactions. The claim lands before a tribunal that lacks the means to interrogate every document. The clerk's perjury tips the scales toward a more permanent guardianship.

Marcello faces the tribunal in the villa's dining room, which has been cleared of plates and set with official chairs. He insists on reading a statement aloud. He recounts each receipt, each payment, each compassionate act he has taken for servants and for the wounded. He places before the court his father's cancelled checks and testimonials from neighbors who say he paid rents on time. Giovanni rises and speaks of communal suffering, of injustice, and of a town's right to recover from the war's toll. He produces the forged papers; he calls witnesses who alter their stories under pressure. The tribunal, tired and canted by war and paperwork, rules that a formal trust will be created to administer Giammarco property for the village's benefit. The decision names Giovanni as a trustee for a period, pending further review.

Marcello hears the verdict and feels his world narrow. The conservator, who has been replaced by a committee of municipal figures, oversees the handover. Marcello walks through the villa with a small suitcase of personal items: his father's watch, a stack of photographs, the gold chain he had given Maria returned to him folded in a handkerchief. He places the watch on the mantel, sets the photographs on a table, and walks to the iron gate. At the gate, the soldiers who were once stationed there now go about their tasks as civilians. Maria approaches with a broom in hand and pauses when she sees him. For a long minute they stand looking at one another. She says nothing about the verdict. He asks if she regrets accepting the housekeeper post. She says that she does not know what regret might mean now. He tells her that he will leave the villa but that he will not leave without one last thing: a look at the rooms he grew up in. She gives him permission to stay for the evening so he may retrieve what is his. He walks through the empty ballroom, through the map room where the Austrians had drawn arrows in chalk, through the small chapel his father once used, and finally to the garden where a statue of a saint stares over hedges caked with frost.

In the final scene Marcello stands alone beneath the statue with the last of the light. The conservator's men lock the doors behind him. He takes the gold chain from his pocket and lays it on the statue's base, as if returning it to a place of no use. Maria watches from the kitchen doorway as he bends to retrieve a sprig of rosemary that once grew in the family herb bed; he tucks it into his coat. He walks out through the gate that clicks shut behind him. Giovanni watches from the tavern window as Marcello leaves with nothing but his small suitcase and the watch. The townspeople mill in silence, their faces unreadable. The villa stands behind them, now under the control of the municipal trust; the hospital cots remain, but fewer men lie there. Maria returns to her broom and resumes sweeping the tile floor.

The last image shows Marcello walking away along the rutted road toward Palmanova, his figure small against the fields, while the villa's lights go dark one by one. The registry of property transfers moves forward inside rooms he can no longer enter. Soldiers and officers, officers and townsfolk, a profiteer and a conservator, a brothel turned to Austrian customers and a housekeeper who will not be his: each performs the tasks that war and misfortune demand. Marcello, now dispossessed in practice though not in law, keeps his head raised and walks on, holding his father's watch and the rosemary, carrying a name that will be argued over for months to come. The film closes with the villa receding behind him and the road ahead blurred by rain.

What is the ending?

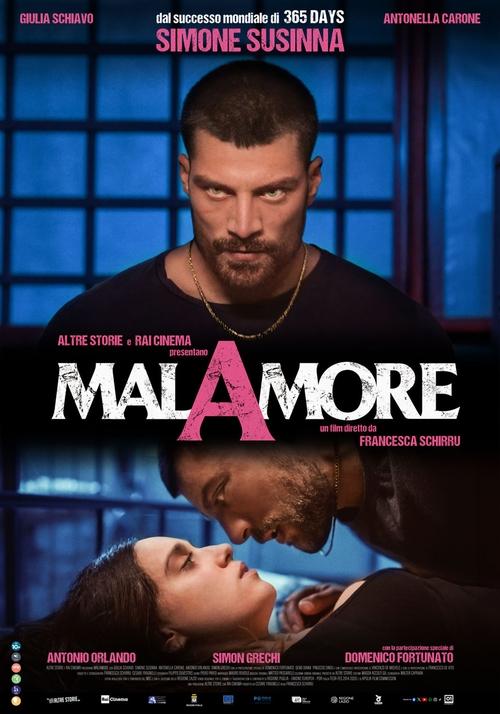

The ending of MalAmore (2025) shows Mary breaking free from her toxic relationship with the criminal Nunzio, choosing love and a new life with Giulio, the riding instructor. Nunzio's vengeful plans culminate in a confrontation, but Mary's courage and the support of her friend Michele help her escape the cycle of violence and fear.

In the final scenes of MalAmore, the narrative unfolds with Mary fully committed to leaving Nunzio, despite the danger this entails. The story begins with Mary and Giulio sharing moments of genuine affection and hope, symbolizing her newfound strength and desire for freedom. This is a stark contrast to the oppressive atmosphere that surrounded her with Nunzio.

Nunzio, feeling deeply betrayed by Mary's choice, intensifies his plans for revenge. The tension escalates as Michele, Nunzio's partner and Mary's childhood friend, warns Mary about the risks of defying Nunzio. Despite these warnings, Mary's resolve does not waver.

The climax occurs when Nunzio confronts Mary and Giulio. The scene is charged with emotional and physical tension, highlighting the dangerous consequences of Mary's decision. However, Michele intervenes, torn between loyalty to Nunzio and his friendship with Mary. This intervention prevents immediate violence, allowing Mary and Giulio to escape.

The film closes with Mary and Giulio leaving the town, symbolizing a break from the past and the toxic environment Nunzio represented. Michele remains behind, his fate ambiguous but marked by his conflicted loyalties. Nunzio is left isolated, his plans for revenge thwarted but his presence still looming as a reminder of the violence Mary escaped.

This ending emphasizes the themes of love as a transformative and renewing force, contrasting with the destructive nature of fear and control. Mary's journey from fear to courage, supported by friendship and love, is the core resolution of the story.

Is there a post-credit scene?

The movie "MalAmore" (2025) does not have any publicly documented post-credits scene. Available sources, including detailed plot summaries and reviews, do not mention or describe any scene occurring after the credits. The film concludes its 107-minute runtime without additional scenes or teasers following the credits roll.

No listings of 2025 movies with post-credits scenes include "MalAmore," and no fan or critic reports indicate the presence of such a scene for this drama-romance film. Therefore, viewers can expect the story to end with the main narrative conclusion and credits, without extra footage or post-credits content.

What motivates Mary to pursue a relationship with Giulio despite the dangers posed by Nunzio?

Mary is motivated by her desire to escape the toxic and criminal relationship with Nunzio. Her love affair with Giulio, a new riding instructor, gives her the courage to seek freedom and a new life, even though she fears the repercussions from Nunzio and is warned by Michele, Nunzio's partner and her childhood friend.

How does Michele's relationship with Nunzio and Mary influence the unfolding events?

Michele is Nunzio's partner and Mary's childhood friend who warns Mary against pursuing her love with Giulio. Michele's loyalty to Nunzio and his warnings add tension to the story, as Mary chooses to follow her heart despite these cautions, which escalates the conflict and leads to Nunzio's vengeful actions.

What specific actions does Nunzio take in response to Mary’s betrayal?

Feeling betrayed by Mary's choice to be with Giulio, Nunzio plots revenge. The film portrays Nunzio's reaction as a vengeful rage that drives the story's tension, highlighting the dangerous consequences of Mary's decision to break free from him.

How does Giulio’s character influence Mary’s transformation throughout the film?

Giulio, the new riding instructor, represents a source of strength and hope for Mary. His presence and their love affair empower Mary to find the courage to challenge her oppressive situation with Nunzio, marking a pivotal point in her emotional and personal transformation.

What role does the setting of southern Italy, specifically Puglia, play in the story’s development?

The setting in southern Italy, particularly Puglia, provides a culturally rich and atmospheric backdrop that intensifies the story's themes of love, friendship, and revenge. The regional context underscores the social and criminal dynamics that trap Mary and influence the characters' interactions and decisions.

Is this family friendly?

The movie MalAmore (2025) is not family friendly and is more suitable for mature audiences due to its themes and content. It is a drama and romance film centered on a young woman, Mary, trapped in a toxic and criminal relationship, which leads to intense emotional and potentially violent situations.

Potentially objectionable or upsetting aspects for children or sensitive viewers include:

- Themes of toxic and abusive relationships involving criminal behavior.

- Emotional distress and tension arising from secret affairs and vengeful rage.

- Possible depiction of violence or threats linked to the criminal elements in the story.

- Mature romantic content and complex adult situations.

There is no indication that the film contains explicit graphic violence or sexual content beyond what is typical for adult drama/romance, but the overall tone and subject matter are likely too intense and emotionally challenging for children or sensitive viewers.

Therefore, MalAmore is best avoided by children and those sensitive to themes of abuse, toxic relationships, and emotional violence.