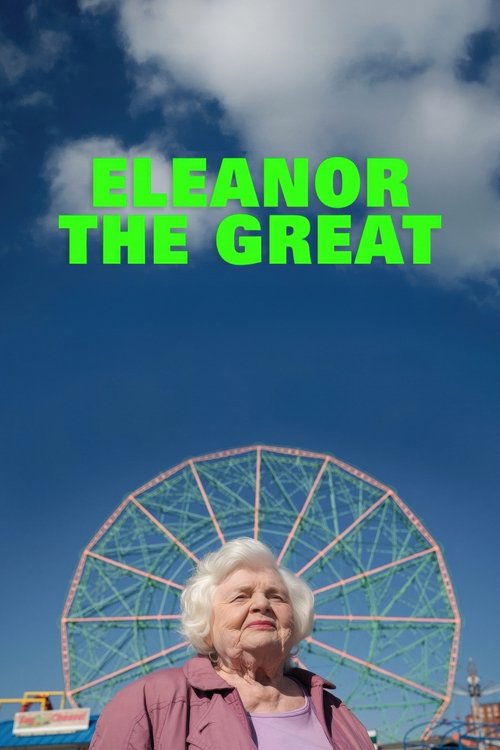

Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

The film opens on a bright afternoon when Jack Jefferson stands in the center of the ring, anticipated and resented in equal measure as the first Black heavyweight champion. Reporters crowd the apron, promoters whisper into one another's ears, and men in suits from Washington watch his movements with the patience of men who mean to entangle him. Outside the arenas, federal agents begin to close in. Jefferson is pulled into the federal system on charges under the Mann Act; authorities accuse him of transporting women across state lines for illicit purposes. They arrest him, arraign him, and use the court calendar as a weapon to puncture his life. This pattern repeats over months: grand juries convene, subpoenas arrive in the middle of the night, and newspapers print both his triumphs and his alleged transgressions in the same breath. The state's pressure forces him to leave the country; he accepts exile in Europe rather than submit to endless prosecutions on charges that humiliate him publicly and legally erode his power.

As he departs, the film follows the collapse of his domestic life. Eleanor, the woman who lives with him as his common-law wife, confronts him in their New York apartment. She tells him that she fears not for his title but for his ruin; she scolds his late-night parties, his appetite for white women, and the endless legal distractions that the headlines create. Their argument sharpens: Eleanor insists he should placate the boxing establishment and give up the championship quietly so they can live in peace; Jefferson, proud and defiant, refuses to hand his belt to men because they ask. Eleanor packs a bag and leaves the apartment, telling him she cannot watch him throw away everything she values. She walks out of his life and closes the door on him in anger and fear.

In exile in Europe, agents still shadow Jefferson's movements. He travels to Paris and London, but American newspapers follow him there, printing columns that attack his morals more than his boxing. Meanwhile, Black leaders in the United States--preachers, politicians, and community figures--refuse to defend him publicly. They meet in parlors and church basements and grant interviews to wire services, explaining that his lifestyle and his relationships with white women have alienated them. Eleanor's name comes up in those conversations, and even the men who once cheered Jefferson's victories refuse to vouch for him. Hedonism and interracial liaisons separate him from the leaders who once might have offered support; their silence shapes his isolation.

The boxing world tightens its grip. Promoters and managers from the athletic commissions lean on him to "take a dive" in a major defense and let a white contender become champion. Jefferson receives offers and threats: friends in the sport tell him that his title will be safer if he cooperates with the establishment's unwritten rules. Men in dressing rooms tell him his life will be easier if he yields; syndicates hint at opportunities if he complies. He refuses the bribe and the pressure every time. Pride governs his choices; he insists that no one will buy his title from him and that he will not concede the ring to satisfy public prejudice.

When a challenger emerges--a huge white fighter known only as "The Kid," a towering man who trains like a machine--the promoters arrange a title defense in Havana, Cuba. Jefferson returns to America for the trip south, his legal troubles still unresolved but his reputation intact in the ring. Eleanor does not rejoin him. She remains in New York, her absence a wound he does not quite acknowledge. The Kid is a physical specimen: taller by several inches, massive in reach, and presented in publicity as a spectacle to restore the title to a different order. Jim Beattie, a real-life boxer, brings the role of the challenger to the screen; the film shows him arriving in Havana with handlers, trainers, and press escorts. The Cuban arena fills with tourists, expatriates, and a smattering of local fans; Havana's warm wind carries the noise of the crowd onto the sand outside the stadium.

On fight night the camera follows a small Black boy who sits at ringside with his father. The boy stares at Jefferson with a mixture of awe and fear; he clutches his father's hand whenever The Kid lands a heavy blow. The crowd alternates between roaring for the challenger and whispering about the politics of the bout. Jefferson walks to the ring in a simple robe, hands wrapped precisely; he nods to his corner men, and the bell starts the first round.

The fight becomes a sequence of specific exchanges. In the early rounds Jefferson uses speed and footwork to avoid The Kid's reach, scoring with jabs and short hooks to the body. The Kid absorbs the early punishment and swings for match-ending blows, connecting occasionally with overhand rights that jar Jefferson. By the seventh round Jefferson racks up points on flurries of combinations, and in the ninth The Kid staggers him with a left uppercut that forces Jefferson to clinch. His corner gives clear instructions between rounds: keep moving, avoid the long reach, and exploit the challenger's slower recovery. The little boy at ringside jumps when Jefferson knocks The Kid into the ropes in the twelfth; the crowd erupts, believing the champion will finish strong.

The middle rounds intensify. In the fifteenth round The Kid catches Jefferson with a crushing right that sends him to the canvas briefly; he rises at the count and stumbles back to his corner. The referee inspects him and allows the fight to continue. In the twentieth round Jefferson mounts an offensive, landing a sequence of lefts and rights that swell the challenger's cheek with a cut. Trainers from both corners argue over seconds and tactics while the announcer's voice drones about the callous interplay of race and sport. Promoters in the ringside boxes sip brandy and watch the economic logic of the match unfold.

As the fight approaches its final phase, physical wear becomes evident on both men. Jefferson's breathing grows ragged, and The Kid's legs thump with exhaustion. The crowd counts the rounds aloud as the bell rings for the twenty-sixth. The referee comes in front of them and pushes them apart; both men touch gloves as a courtesy that looks more like ritual than respect. In the first minute of the round The Kid lands a heavy hook to Jefferson's left temple that flashes the champion's vision. Jefferson staggers, and with a right that seems designed to end the contest The Kid drives into his ribs; Jefferson bends forward, fighting to keep his balance.

Then a sequence unfolds that the film captures in long takes. Jefferson falls to his knees after a sweeping blow and then to his side on the canvas. The crowd screams; ringside doctors and the referee rush toward him. Jefferson does not push himself up. He lies face down, hands splayed on the canvas, and breathes shallowly. The referee looks at him, counts aloud to ten, and then, after a hesitation, waves his arms to signal the end. The Kid is declared the new heavyweight champion. Cameras flash; men in the crowd shout approval. The little boy at ringside cries out the name "Jack" and then goes silent, his father covering his mouth.

Backstage, trainers and managers swarm the ring. Some men embrace The Kid, slapping him on the back as the belt is presented; his handlers lift him onto their shoulders. Jefferson's corner men kneel beside him and gently try to pull him to his feet. He allows them to help him to a sitting position but offers no protest when they remove his gloves. He does not offer any press statements or denials; he stares at his hands as if measuring the loss. The camera finds Eleanor in the audience, watching from afar with folded arms and tears on her cheeks; she does not move as reporters approach her. Later she tells no one that she has come to Havana and then slipped away, choosing to see the final moments of their relationship from a distance.

After the fight, rumors circulate in locker rooms and in editorial rooms that he has given the match away on purpose. Some of his contemporaries insist he took a dive to avoid more trouble at home; trainers in back alleys recount whispered conversations that took place in hotel lobbies. Jefferson himself remains silent in public. Years later, when interviews are granted and memoirs are published, he claims that he has taken a dive in that last round--an assertion he makes in conversations meant to explain the choice he made under duress and humiliation. The Kid, who in private life bears the name Jess Willard in the historical account that inspires the story, laughs about the suggestion; when asked about Jefferson's later claim, he tells friends, "If he was gonna take a dive, I wish he'd done it a lot earlier." He treats the idea as absurd, implying that he felt his victory was earned in the ring that night.

In the months that follow, Jefferson drifts between public appearances and private ruin. The federal probes continue to shade his days, and the silence of Black leadership and of Eleanor's absence leaves him vulnerable to both legal penalties and social ostracism. He fights smaller bouts in Europe for money and occasionally returns to America when legal matters force him back, but his aura as champion diminishes. He loses friends who once stood beside him and finds only the mechanical admiration of crowds who remember his speed but not his humanity.

The film closes with an image of the little black boy, now older, standing in front of a small mirror in his Harlem apartment. He practices a boxing jab, mimicking the champion he watched from ringside in Havana. The camera pulls back to show Jefferson, older and unadorned, sitting in a spare hotel room in Paris. He turns a photograph in his hands--an image of himself and Eleanor on a happier day--and places it back into an envelope. He breathes, looks at the window where the city lights form a distant constellation, and then places the envelope into a drawer. The scene cuts to a cemetery in a cold winter light where no funeral has yet been staged; the film lets the silence hold a space for what might have been. Titles roll with the historical note that the film and the original play draw from the real life of Jack Johnson and that the challenger who wins in Havana is inspired by Jess Willard, whose recollection of Johnson's post-fight claim is that he laughed and wished the supposed dive had happened sooner. The final shot fixes on Jefferson's empty robe hanging on a chair in a dressing room, the fabric still carrying the scent of sweat and tobacco; the last frame lingers on the awarded belt, now in a trophy case, as lights in the arena go out.

What is the ending?

At the end of Eleanor the Great (2025), Eleanor's deception about being a Holocaust survivor is revealed, leading to emotional confrontations but ultimately to a deeper understanding and friendship between her and Nina. Eleanor reconciles with her daughter Lisa, and the film closes on a note of acceptance and connection among the main characters.

Expanded narrative of the ending scene by scene:

The final act begins with Eleanor attending a Holocaust survivors' support group in New York City, where she has been sharing a story originally told to her by her late friend Bessie, claiming it as her own experience. This lie weighs heavily on Eleanor as she grows closer to Nina, a 19-year-old college journalism student who is deeply moved by Eleanor's story and wants to write about her.

One evening, Nina confronts Eleanor after discovering inconsistencies in her story. Eleanor admits the truth--that she is not a Holocaust survivor but had fabricated the story out of a desire to belong and to honor her late friend Bessie's memory. This revelation causes a moment of tension and hurt, especially for Nina, who had connected with Eleanor on a personal and emotional level.

Despite the initial shock, Nina chooses to forgive Eleanor, recognizing the loneliness and grief that motivated her deception. Their friendship deepens as they share honest conversations about loss, identity, and the need for human connection.

Meanwhile, Eleanor's daughter Lisa, who had been planning to place Eleanor in an assisted living facility, comes to understand her mother's emotional struggles and the importance of Eleanor's new friendships. Lisa and Eleanor reconcile, with Lisa offering more support and companionship.

The film closes with Eleanor, Nina, Lisa, and Eleanor's grandson Max sharing a quiet moment together, symbolizing a new chapter of acceptance and intergenerational connection. Eleanor's fate is one of emotional healing and renewed family bonds. Nina gains a meaningful mentor and friend, and Lisa embraces her mother's independence and spirit.

This ending highlights themes of truth, forgiveness, and the human need for belonging, showing how Eleanor's journey, though marked by deception, ultimately leads to genuine relationships and understanding.

Who dies?

Yes, there are character deaths in the movie "Eleanor the Great" (2025). The key character who dies is Bessie Stern, Eleanor's best friend and roommate of 12 years. Bessie's death occurs early in the film and serves as the catalyst for the story. She is a Holocaust survivor haunted by traumatic memories, and her passing deeply affects Eleanor, who then moves from Florida to New York to live with her daughter and grandson.

The circumstances of Bessie's death are not detailed explicitly in terms of cause or setting, but it is portrayed as sudden and jarring. The film opens with a montage showing the close friendship between Eleanor and Bessie, followed by a scene of Eleanor sitting alone on a bench where Bessie would have been, emphasizing the emotional void left by her death.

Bessie's Holocaust past is central to the plot. She had survived Nazi-occupied Poland, including Auschwitz-Birkenau, and had never publicly shared her story before her death. Eleanor, in her grief and loneliness, mistakenly joins a Holocaust survivors' support group and begins to tell Bessie's story as if it were her own, which leads to complex emotional and social consequences.

Additionally, within Bessie's recounted story, her brother dies during their escape from the Nazis. They both leap from a moving train to escape capture; Bessie survives, but when she backtracks to find her brother, she discovers him murdered, riddled with bullets. This traumatic event is part of Bessie's harrowing past shared in flashbacks.

No other character deaths are prominently described in the sources. The film focuses mainly on Eleanor's processing of grief after Bessie's death and the emotional fallout from Eleanor's assumption of Bessie's Holocaust story.

Is there a post-credit scene?

The movie Eleanor the Great (2025) does not have any publicly documented post-credit scene. None of the available sources, including detailed reviews, cast and crew listings, or film summaries, mention a post-credit or mid-credit scene for this film. The film concludes with the main narrative arc resolving Eleanor's transformation and her impact on other characters, with no indication of additional scenes after the credits.

What is the nature of Eleanor's friendship with the 19-year-old student Nina?

Eleanor, a 94-year-old woman, strikes up an unlikely friendship with Nina, a 19-year-old college journalism student in New York City. Nina becomes interested in Eleanor after hearing her story and wants to write a paper about her, leading to a friendship that develops as Eleanor shares her experiences, including the lie she tells about being a Holocaust survivor.

How does Eleanor become involved with the Holocaust survivors' support group?

Eleanor attends a singing group at the local Jewish Community Center on her daughter Lisa's suggestion but accidentally ends up at a Holocaust survivors' support group. When the group asks her to share her story, Eleanor panics and recounts the story of her late best friend Bessie, claiming it as her own.

What role does Eleanor's family play in the story?

After the death of her best friend Bessie, Eleanor moves to New York City to live with her daughter Lisa and grandson Max. However, they have their own busy lives, leaving Eleanor mostly alone during the day, which motivates her to seek companionship and social interaction outside the family.

What themes are explored through Eleanor's storytelling and the lie she tells?

The film explores themes of grief, loneliness, identity, and the power of storytelling. Eleanor's lie about being a Holocaust survivor leads to a complex situation that examines how stories we hear can become the stories we tell, and the consequences that arise from deception, especially in the context of memory and history.

How is Eleanor's character portrayed throughout the film?

Eleanor is portrayed as witty, proudly troublesome, and initially spiky, but as the story progresses, her character becomes more hollowed out, with much of her personality centered around her grief for her late friend Bessie. The film shows her navigating loneliness and the challenges of aging while engaging in a fish-out-of-water narrative in New York City.

Is this family friendly?

The movie Eleanor the Great (2025) is generally recommended for viewers aged 12 and older, including teenagers and adults, but parental guidance is advised for sensitive children due to some mature themes.

Potentially objectionable or upsetting aspects for children or sensitive viewers include:

- Mentions and references to the Holocaust, which are handled seriously and may be emotionally intense.

- Themes of grief, loss, and family reconciliation, including the death of close family members, which might be upsetting for some viewers.

- Some lying and mild foul language appear in the film.

- A brief mention of a character's sexual orientation is included, but without explicit content.

- The film contains emotionally complex and sometimes poignant moments that explore difficult life experiences, which may be challenging for younger or sensitive audiences.

There are no reports of graphic violence, nudity, or intense frightening scenes. The tone is described as comically poignant and realistic, focusing on emotional depth rather than sensational content.

In summary, Eleanor the Great is a thoughtful, character-driven drama suitable for older children and teens with parental guidance, especially for those sensitive to themes of loss and historical trauma.