Ask Your Own Question

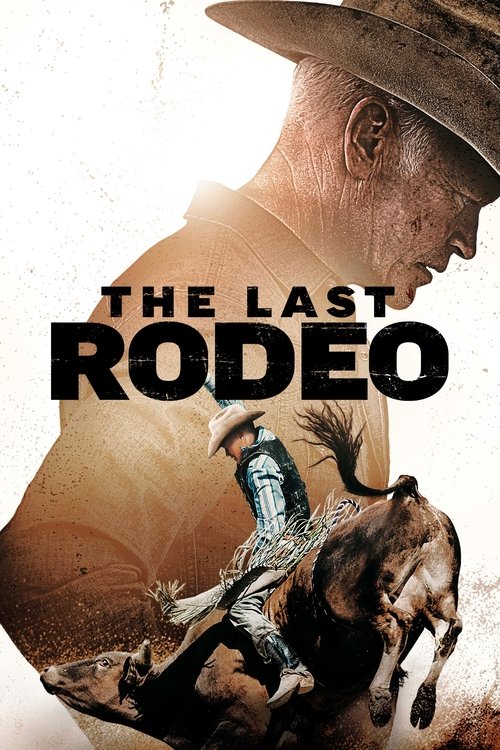

What is the plot?

The film opens inside a small, dimly lit clinic where Joe Wainwright sits rigidly in a vinyl chair. A neurologist steps out into the hallway with a manila envelope and a slow, professional face. The doctor tells Joe that his grandson has a brain tumor that requires an invasive neurosurgical procedure, that the operation is complex and expensive, and that the hospital's billing department has determined the family's insurance will not cover the full cost. Joe slides the envelope across his knees, reads the estimate printed on the forms, and exhales as if the breath will not return.

At home, Joe pads through a modest trailer that bears faded photographs of championship banners and one black-and-white image of him younger, hat tipped and arm raised. He is a former world champion bull rider, a man who once earned the highest honors in his sport. The camera lingers on a neck brace tucked into a closet and on a framed newspaper clipping that mentions a career-ending injury. Joe turns the clipping over with a thumb and remembers, in flash, a past ride that ends in the ear-splitting snap of bone and the blur of white lights. The scene cuts back to the present: Joe reads a letter from the Department of Veterans Affairs. The veteran benefits that he receives do not cover the lion's share of his grandson's surgery.

Later that day, Joe walks through a small town fairground as twilight sets in. He pauses beneath a poster stapled to a light pole: Professional Bull Riders is holding a one-night-only legends competition open to former champions and retired riders, with a first-place prize of $750,000. The flyer notes the event welcomes "all former legends" and warns explicitly that contestants must sign an insurance waiver. Joe touches the edge of the paper, fingers crinkling the corner, and looks up at the empty bleachers beyond. He carries into his bones the memory of when he broke his neck, when he was drunk and reckless, and of the day his life narrowed to physical therapy and apologies. He also remembers the little face of his grandson from the clinic, the way the boy's mother wept in the hallway. Joe calls the number on the poster before the air cools.

He goes to a PBR event office the following morning to register. A clipboard changes hands. An official reads aloud the competition rules and explains that the field is stacked with former champions and that this will be the oldest entry list in the organization's history. Joe signs an insurance waiver that lists risks in capital letters. He signs anyway, the pen shaking but not faltering. A woman behind the counter studies his signature and asks his age; when Joe tells her, she makes a note and looks at him differently, with a calculation that is both pitying and admiring.

At home, Joe finds that his presence reverberates through the small family he has left. His daughter arrives with groceries and a face hardened by care. She had been the one to sit with Joe during his rehab after the neck injury; she had patched him together when hospitals and bottles had broken him. She had set aside her own dreams and professional pursuits because their household needed steady hands. She looks at Joe now and says nothing for a long time; her silence contains every unpaid bill and every canceled audition. They argue in the kitchen over the intrusive nature of his decision. She points at the insurance waiver in his hand and asks what he thinks he will ride for, whether he expects miracles from a rodeo ring. Joe replies with short, clipped sentences; he says he is not asking for permission. He is asking for a chance.

Joe begins to train -- not in the way he trained as a young champion, but with the slow, practical regimen of a man mending an old instrument. He visits a local indoor arena where a retired stock contractor brings out a mock bull made of padded wood and leather. Joe mounts the practice bucking apparatus, his fingers finding calluses and scar tissue, his legs remembering stance and balance. He works with a coach who is younger and blunt; the coach watches Joe fall and rise, bandage a scraped elbow, adjust his belt, and say, matter-of-factly, "You don't get the years back." Joe does not correct him. He takes painkillers only when he must and sleeps poorly, waking with flashes of white light from the accident, with the memory of whiskey, with guilt surfacing like a tide.

Phone calls arrive from the hospital with more bills and procedural scheduling. Joe sits through them at a card table and marks dates with a pencil whose eraser he wears down. His daughter watches him and, at night, packs a small overnight bag to drive Joe to practice. She waits in the truck while he rides and then stands quietly at the gate while he cleans his spurs. When she admits, finally, in a voice hollowed by years of caretaking, that she resents him for the ways his choices ruined their family stability and her ambitions, Joe listens. He does not try to excuse his drinking or his past arrogance. He says instead that the grandson's face from the clinic will not leave him. He asks her, simply, to let him try. She pauses, then puts her hand on his forearm and tells him to come home when he's done.

The film charts Joe's journey to the event in precise detail. He drives an old pickup with a bumper sticker from a past campaign; he stops at a gas station and pays in cash. On the road, time stretches in long, pastoral shots of interstate and fence-line, and Joe hums an old rodeo tune under his breath. Arriving at the arena, he sees other names on the roster that used to be carved into trophies and memory: some arrive with hip braces and canes; others with sonorous presence, confident even in age. The stadium announcer calls them "legends" over loudspeakers while crowds file in under a pyrotechnic sky. Joe checks in at the competitor entrance, receives a number, and is measured for equipment. A young competitor jokes about the old champions; Joe smiles and answers with a dry quip that earns a respectful nod.

On the night of the competition, the venue buzzes. Television crews angle lighting rigs, commentators adjust lapel mics, and an emcee breathes over a microphone to amplify the crowd's expectation. Joe signs another waiver when he steps into the staging area -- a second formality that presses the stakes into his hands. He watches as prerecorded highlight reels replay his older rides in grainy footage, the shots of him as a young man flickering across a jumbotron. The audience applauds for the memory. Joe adjusts his glove and does not look at the screen. He keeps his eyes on the gate, on the path the bulls will run.

Each ride in the competition is described with concrete action sequences. Bull after bull explodes from the chutes: flaring nostrils, dust, a tide of bodies. Joe is called to the chute for his round. He mounts the bull, plants his heels, and grips with a left hand that remembers the rhythm of contracting muscles. The gate snaps open; the animal lunges, then bucks hard. Joe leans back and rides the bull's rapid skewing. In one sequence he loses his balance and slides down the flank, but the bull's momentum shifts and he surges back up, muscles burning. A young announcer calls out the time; a judge raises a flag. Joe hears a smattering of applause and then the crescendo of the crowd. He exits the arena, shakes hands with a competitor, and requests, quietly, that he see a replay of his ride. In another round, an animal spins and Joe grips while a tendon screams in his knee; he hears the crowd like ocean, counts to eight seconds, and the buzzer sounds, indicating a completed ride. The cameramen show Joe's measured face -- a portrait of concentration that is hardly practiced anymore but wholly present.

Between rides, interpersonal dramas unfold. Joe interacts with other legends, trading barbed humor and rough camaraderie. He meets a former rival who taunts him about his drinking days; the rivalry simmers into terse conversation, then into a grudging handshake. His daughter watches from the stands, hands knotted around a program. She leans forward as he mounts for a particularly dangerous bull with a reputation for bucking off older riders. She exerts a small restraint on her anxiety by checking her phone for updates from the hospital; the boy remains in pre-op, the forms still unsigned for a financing arrangement. Joe, in a quiet moment backstage, receives a text message with the surgical dates; he tucks the phone inside his vest and breathes, then walks into the ring.

The competition reaches its late rounds. The announcer narrows the field to a handful of final contestants, including Joe. The clocks on the jumbotron count down as each bull is introduced with dramatic cutaways to previous rodeo glories. Joe stands in the pen with his hand on the rail, feeling the coarse hide of the chute under his fingers. A handler releases the animal and it charges; Joe rides with the memory of his neck snapping in the past still present in his body. He clamps his jaw and postures himself as if the years were only belt loops to step over. During his final ride, the bull rears and bucks erratically; Joe shifts his weight and manages to keep his balance until the bell sounds. When the bell rings, the audience rises. Judges confer. A board displays scores; Joe's number climbs into contention. He does not celebrate. He walks off the arena floor and into the tunnel where medical staff check riders for injuries and where sponsors ask for quick interviews. A camera asks him about the motive for coming out of retirement; he answers plainly that his grandson needs a surgery that they cannot afford, and that he came for the money.

The film gives space to reconciliation scenes that are not shorthand but concrete and action-based. Joe and his daughter sit in a cramped RV behind the arena after the final round and open a half-bottle of coffee. She tells him, in measured sentences, about the ways she had held the family together after he broke his neck, about the nights when she read to a small child while he slept off pain and shame. Joe listens and then reaches for her hand, grips it, and apologizes for the years he wasted in bars rather than at her side. He tells her he is sorry for stealing her college fund and for not being a father who showed up. She breaks into a small, hard laugh and says that she forgave him once he changed, but that forgiving is a different chore than trusting. He asks her once more to trust him now and she studies his face. Finally she nods -- not a full surrender but a concession that the need is genuine. She tells him to ride for the boy.

The competition announces its winners onstage beneath stadium lighting. The emcee calls out placings, reads scores aloud, and pauses when he reads Joe's name among the top finishers. A montage shows Joe signing more documentation backstage -- tax forms, prize acceptance papers, and a final release. He pockets the envelope with the check stub. He drives home in the predawn, tired and aware of the weight in his jacket. He arrives at the hospital and slips into a hallway where fluorescent lights hum. He touches his grandson's forehead gently as the boy sleeps between pre-surgery and sedation. Nurses move with quiet efficiency. Joe meets the child's mother in the waiting area; she looks at the check he passes forward and says nothing aloud, but her mouth trembles. Joe watches a surgeon wheeling in a clipboard and the boy's mother signs necessary consent forms. Joe leaves the hospital to sit in his truck and waits, counting cigarettes he does not light.

The film culminates in a final set of exchanges in which Joe demonstrates courage concretely rather than declaratively. He shows up at the operating wing, removes his hat, and speaks quietly with the surgeon. He places his hand on the boy's shoulder before the anesthetic takes hold, and he tells the child, with clumsy but honest words, that he will be waiting when the boy wakes. The surgical team moves through its protocols and the operating theater door closes. Joe does not sleep; he paces the hospital hall and revisits the rodeo footage on his phone, watching slow-motion replays of his rides as if memorizing the pattern of motion. Nurses bring coffee at dawn. The surgeon emerges hours later and reads the post-op notes aloud: the operation was invasive and complicated but completed, and the prognosis is cautiously optimistic. Joe exhales as if he has been holding his breath since the first clinic visit. He steps into the recovery room when the boy opens his eyes and murmurs, and Joe squeezes the child's hand with a mix of relief and exhaustion.

In the closing scene, the film returns to the fairgrounds where the PBR event staged a last-chance night for legends. Joe stands by the arena after the crowds have dispersed, hands in his pockets. He picks up a stray program, smooths it, and walks toward the chute as if to say goodbye to an old life. His daughter meets him at the gate; she wraps an arm around his waist without speaking. They walk together up the steps and stand on the edge of the ring. Joe looks out at the empty seats and then at his daughter and grandson, who is now sitting in a wheelchair beside her and watching the arena lights with a soft focus. He puts his hat on and steps into the dust of the corral. He mounts a practice bull one last time, riding slowly, steady, and with purpose. The camera holds on his face as he keeps his balance; it lingers on the small, steady hand of the grandson waving a tiny, brave wave. The film ends with Joe returning to his family, his arms full of a victory that is measured not simply in prize money but in the tangible choice to put everything at stake for the boy's life.

What is the ending?

Short Narrative of the Ending: Joe Wainright, a former bull-riding champion, participates in a high-stakes "Legends" competition to fund his grandson's critical surgery. Despite suffering serious injuries during the competition, Joe demands a re-ride, which he excels in, eventually securing a high place. The film concludes with Joe's resilience and determination helping him overcome his personal demons while supporting his family.

Expanded Narrative of the Ending:

The ending of The Last Rodeo unfolds with Joe Wainright, a retired bull-riding champion, facing a critical moment in his life. His grandson, Cody, requires an expensive surgery to remove a brain tumor, and Joe's military benefits and family insurance don't cover enough of the costs. Driven by love and a sense of responsibility, Joe decides to participate in the Legends Rodeo, a high-stakes competition open to former bull riders. This decision is fraught with risk, as Joe had previously broken his neck during a ride and has a complicated past with alcohol.

As the competition ensues, Joe teams up with his old friend and partner, Charlie Williams, played by Mykelti Williamson. Charlie, a devout Christian, tries to guide Joe back to his faith, but Joe is still grappling with anger towards God following his wife's death. Despite these internal struggles, Joe's determination to support his family propels him forward.

During the competition, Joe endures severe injuries when a bull pins his leg against the wall and steps on his knee. Despite these injuries, Joe demands a re-ride, a testament to his unyielding spirit. The doctor clears him to participate, and in a remarkable turn of events, Joe executes a phenomenal ride that catapults him to the top of the leaderboard. This display of resilience and grit showcases Joe's growth and his ability to confront his past mistakes while fighting for his family's future.

The climax of the film highlights Joe's journey from a man consumed by his past to one who finds redemption and purpose. As the competition concludes, Joe's actions demonstrate his love and commitment to his family, illustrating that true courage is not about avoiding challenges but about facing them head-on. The movie concludes with Joe having secured a high place in the competition, suggesting a positive outcome for his grandson's surgery and a newfound sense of peace for Joe himself.

Is there a post-credit scene?

There is no specific mention of a post-credits scene in "The Last Rodeo" (2025) in the provided search results. The movie focuses on Joe Wainwright's journey to save his grandson by competing in a high-stakes bull riding competition, and it concludes with a heartwarming epilogue showing the successful surgery and family reconciliation. If you are looking for detailed information about post-credit scenes, it's best to check specialized movie databases or reviews for any updates.

What motivates Joe Wainwright to return to bull riding after his retirement?

Joe Wainwright returns to bull riding primarily to win the prize money needed to pay for his grandson Cody's expensive brain tumor surgery, which is not fully covered by insurance or military benefits. This urgent family need drives him to risk his life by entering a high-stakes Legends Rodeo competition despite his past severe injury and retirement.

How does Joe's relationship with his daughter Sally evolve during the story?

Joe's relationship with his estranged daughter Sally is strained at the start, especially because she is angry about his decision to ride bulls again. Throughout the story, Joe and Sally work through their past wounds, with Joe reconciling with her as part of his personal journey while trying to save their grandson. Sally had taken care of Joe after his injury and had given up her own professional pursuits, adding complexity to their dynamic.

What role does Joe's friend and trainer Charlie play in the story?

Charlie, Joe's former best friend and trainer, accompanies Joe on his journey to the rodeo. He is a committed Christian who reads the Bible frequently and tries to witness to Joe, who is angry with God over his wife's death. Charlie supports Joe despite their past issues and helps him navigate the challenges of returning to bull riding.

What are some of the major challenges Joe faces during the Legends Rodeo competition?

During the competition, Joe faces several life-threatening challenges: he must convince the event organizer to let him compete despite not initially responding to the invitation; he suffers serious injuries including having his leg pinned and his knee stepped on by a bull; and he demands to be cleared by a doctor to continue riding. Despite these obstacles, Joe manages to perform well, even reaching first place with one day left in the rodeo.

How does the film portray Joe's internal struggle and past trauma?

Joe's internal struggle centers on his painful past, including breaking his neck while drunk and the death of his wife, which has left him angry with God. The film shows Joe wrestling with these unresolved issues as he makes his comeback. However, some critiques note that the film presents these elements through exposition rather than deep character development, with Joe's past and motivations conveyed in monologues rather than fully fleshed-out conflict.

Is this family friendly?

The movie The Last Rodeo (2025) is generally considered family-friendly and rated PG. It is described as an inoffensive family sports drama with positive themes of faith, family, and personal redemption, suitable for most audiences including children with some parental guidance.

However, there are a few potentially objectionable or upsetting elements to be aware of for children or sensitive viewers:

- Mild profanity is present in some scenes.

- Characters are shown drinking alcohol in a bar settings.

- The bull-riding scenes are fairly intense, which may be rough or suspenseful but are not overly graphic.

- The plot involves a family dealing with a serious illness (the grandson's aggressive cancer diagnosis), which could be emotionally challenging.

Overall, the film maintains a positive message and is mainly free from harsh content, violence, or language that would be unsuitable for children, but parents might want to consider the intensity of bull-riding scenes and the emotional themes before deciding for very young or sensitive children.