Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

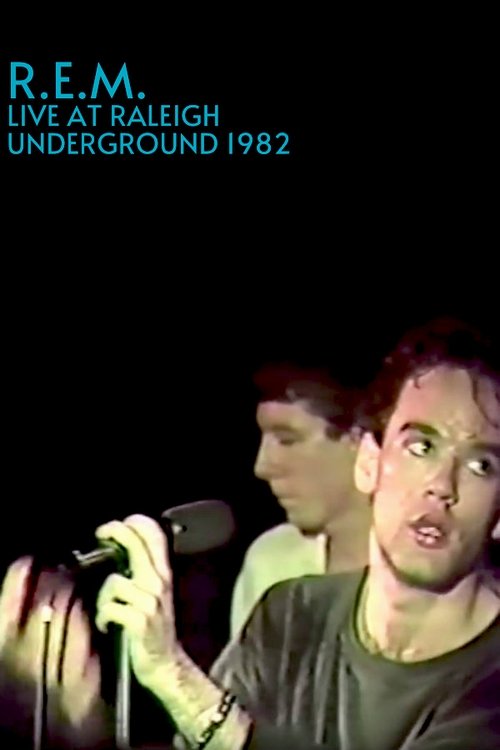

On the night of October 10, 1982, in Raleigh, North Carolina, the cameras are already rolling when the story begins. It is sometime after dark in the low-ceilinged club called the Raleigh Underground, also known as The Pier, a basement bar where the stage is barely a step up from the floor and the lights are a handful of colored cans throwing humid beams through cigarette smoke. The room is packed shoulder to shoulder with college kids and early adopters, the sort of crowd that still calls this strange new sound "college rock" because no one has thought to call it alternative yet. On that cramped stage, four figures are setting their gear, checking cables and tunings, talking softly among themselves over the restless murmur.

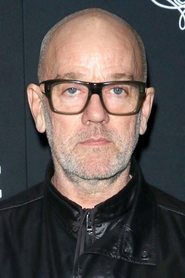

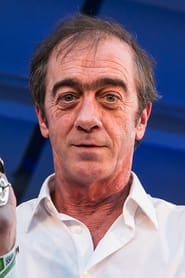

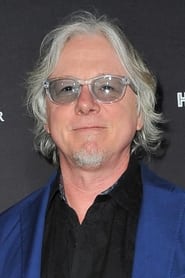

These are the only real "characters" this night will need. At center, with a too-long mop of hair that he lets fall into his face, stands Michael Stipe, the singer, lanky in a thrift‑store shirt, hand wrapped around a microphone he keeps adjusting like it never quite sits right. Stage right, in a dark jacket and a guitar slung low, Peter Buck leans down to fiddle with his Rickenbacker, fingers picking out bright arpeggios that cut through the dull room chatter. To the singer's left, Mike Mills in big glasses and a striped shirt bounces on his heels even before the first note, his bass already hanging against his chest like a promise. Behind them, almost hidden by cymbals, Bill Berry rolls a stick against a snare head, testing the give of it, the unassuming backbone of the whole enterprise.

They are young and not yet famous, two months removed from the August release of their first EP, Chronic Town, still six months away from the debut album Murmur that will change their lives. The cameras that have been set up around the room--the earliest known professional crew to film this band--are here for a simple purpose: to document a set for TV broadcast from a tiny North Carolina club on this precise date, October 10, 1982.

There is no narrator to open this, no title card explaining the stakes. The tension is buried instead in that gulf between what the band is now and what it is about to become, a future that only the audience watching decades later can see. On the floor, the kids in the front row just know that something is about to start.

A small clatter of drums; someone off‑mic says something indistinct; there is a low chord from Buck's guitar that hangs in the air like a curtain about to be drawn. Stipe steps closer to the microphone, pushes hair from his eyes, and without preamble the band slams together into "Wolves, Lower," the opening song of the night and of the setlist that will later be written down and passed around as a relic.

The sound hits fast and jangling, Berry's drums tumbling forward, Mills' bass darting under Buck's chiming pattern. Stipe grabs the mic stand with both hands, body jerking in short, awkward spasms that look like he's trying to shake off self‑consciousness. The lyrics come out in a rush of slurred syllables, hints of southern imagery and mysterious phrases, more texture than exposition. There is no spoken explanation for what "wolves, lower" means; the song just exists, a mood that fills the room and immediately silences the background conversations.

The cameras never cut away to any other place. The Raleigh Underground is the only world here. Behind the band, a wall painted dark, a few posters, cables snaking under their feet. Off to one side, the silhouette of Mitch Easter, the producer who helped shape the sound of Chronic Town and will soon co‑produce Murmur, leans within arm's reach of the stage. Now and then he will step into view, a reminder that offscreen there is another layer of history being written, a producer checking in on a band he knows is on the verge.

"Wolves, Lower" ends on a clipped, tight stop, Berry's final cymbal crash hanging over quick applause. For a second, there is that suspended, charged silence that always falls right after a band proves it came to play. Stipe leans toward his bandmates, says something we cannot hear over the lingering feedback. Then he turns back to the microphone.

"This is called 'Laughing,'" he says, or something close to it--stage banter is brief, half‑mumbled, part of the rhythm of the set more than any narrative. The transition is immediate: Buck's guitar rings out the opening figure of "Laughing," Mills' harmonies waiting just behind Stipe's lead. The tension now is not life and death; it is artistic, the pressure to follow one strong song with another and to keep this crowd in their grip.

Michael's voice, a little off‑tune in places according to later commentators, veers around the notes with a combination of nervousness and bravado. He moves more now, hair flying, occasionally glancing sideways like he is checking whether this is all really happening. Mills' backing vocals slide in, a bright counterpoint that already hints at the band's signature blend, his eyes mostly closed, a small smile betraying how much he is enjoying himself.

Again, there is no explanation between songs about who these people are or why they wrote what they wrote. The crowd doesn't need it. The cameras just keep collecting proof that this band can deliver live.

The song crashes to a close, and before the room can exhale fully, the band charges into "1,000,000." This third song ups the energy again, a blur of words that sound half like numbers, half like invocations, Stipe gripping the mic stand so hard the base rocks against the scuffed floor. The "confrontations" here are internal: the band versus its own limitations, their inexperience colliding with the tightness they have honed night after night on the road. Buck occasionally glances down at his fretting hand, making sure every chiming pattern lands exactly where it should. Berry, sweating now, drives the brisk tempo, never showy, always locked in, shoulders stiff with concentration.

By the time "1,000,000" snaps shut, applause is louder, the crowd's movement more visible at the front of the stage. Someone shouts something unintelligible; a hand with a plastic cup briefly rises into frame. The night is still young, but the momentum is building.

Stipe leans into the mic and, in his soft Georgia drawl, tosses out a short phrase--maybe a song title, maybe a cryptic aside. Then a jagged, off‑kilter guitar figure slices through the air. It is "Moral Kiosk," another pre‑Murmur song that the audience hasn't yet seen on an album jacket but is already learning to shout along with. The lyrics, dense with surreal images, swirl around a propulsive beat. Mills' bass lines push against Buck's angular patterns, the sound a little darker, more anxious.

Stipe's performance in "Moral Kiosk" shows a different side: eyes closed more often now, he leans into the mic as if confiding a secret that he can barely hear himself. The tension in his shoulders spreads down his arms; he occasionally pulls the microphone away as though wrestling with the impulse to say more than he is ready to share. The crowd doesn't know what the song is "about," but they feel what it does in the room: the club seems to narrow, the lights flicker across sweat‑sheened faces, and the whole thing feels like a sermon with no clear doctrine.

When it ends, the applause is a release. Stipe mutters something that might be "thanks," or maybe just an exhale. The band barely pauses. Berry taps his sticks together; Buck shifts his guitar strap higher on his shoulder. The opening of "Catapult" spills out, chiming and insistent.

"Catapult" raises the emotional register again, with its yearning melodic line and a rhythm that feels like it is forever leaning forward. Mills' harmonies ring loud and clear, his voice intertwining with Stipe's, providing lift where the lead vocal still wanders, nervous and sharp‑edged. Here, something important is quietly established: the dynamic where Mills, smiling, animated, seems to hold the songs together from the side of the stage, while Stipe in the center pulls inward and outward at once, the reluctant focal point.

As the chorus repeats, Stipe tilts his head back, eyes still partially veiled by hair, and sings not exactly to the crowd but into the charged space above them. The club lights strobe across his face, flattening his features for the camera before plunging them back into shadow. The tension is no longer just whether the band can make it through the set; it is whether Stipe can accept being seen so closely, recorded and broadcast, his earlier shyness crashing up against the public role he is stepping into.

When "Catapult" ends on a ringing chord, there is a beat where no one moves. Then the audience roars as loudly as a room this small can roar. The band turns inward again, exchanging quick glances, the sort of small acknowledgments that say: this is working.

The next shift in the story comes with "West of the Fields." Buck strikes a more urgent pattern, the notes tumbling in tight clusters. Berry kicks in with a driving beat that feels more martial, more insistent. Stipe's lyrics here are even more cryptic, referencing landscapes and distances, a sense of being on the edges of known territory. The song, which will close Murmur in a few months' time, is already fully formed, the band stepping into a sound that is moody and confident and unmistakably theirs.

As "West of the Fields" builds toward its ending, the small club feels as if it contains something disproportionate to its size. The historical tension--unfelt by those present, but strong for later viewers--is that this is the sound of a band writing the blueprint for a new corner of American music, in real time, in a literal underground space below street level. The cameras bear silent witness, zooming in on Stipe's clenched jaw, tracking Buck's right hand as it skips across strings with more command now than at the top of the set.

The song ends in a tangle of guitar and drums, and again, the crowd pushes forward, hungry for the next moment. Stipe bends at the waist, hands on knees, catching his breath. There is sweat darkening his shirt now; Mills' glasses slide down his nose as he laughs at something Berry has said behind him. The moment is mundane and utterly human, but the cameras fold it into the visual record: this is what a band looks like before myth accumulates, when they are still just four guys in a cramped club in Raleigh on a Sunday in October.

Then comes a different kind of turning point. Stipe lifts his head and, more clearly than usual, announces the next song: "Radio Free Europe." The title lands. Even in 1982, this is already the band's calling card, the single that college stations have been spinning, the song that got them noticed by I.R.S. Records and led them to the Chronic Town EP that brought them here.

Buck hits the familiar opening riff, bright and looping; Berry drops into the snare pattern that feels like a locomotive getting up to speed; Mills' bass is taut and driving. The crowd cheers as soon as they recognize it. This is as close as the set has to a hit, and the energy in the room spikes accordingly. Stipe steps up to the microphone with a little more assurance this time. His voice still smears words together, syllables muttered and swallowed, but the melodies are sure, the cadence locked in. The years of future radio play, MTV rotation, and critical praise lie unseen ahead, but in this room the song is already a climax of the first half of the set.

"Radio Free Europe" is, structurally, the first true pinnacle of the night. The band is tight, the crowd engaged, the cameras catching every angle of these four players as they demonstrate exactly why someone decided to point professional lenses at them. Mills leans into the mic for harmonies on the "Radio station" lines, his voice both grounding and lifting the chorus. Stipe's whole body vibrates as he sings, one hand occasionally leaving the mic stand to slash the air in time with a drum hit.

When the song ends, there is no false modesty. They know they did it justice. Stipe lets a quick smile escape as he steps backward, away from the mic. Berry twirls a stick. Buck looks down to retune, but his posture has subtly loosened. They have crossed a threshold: the set has moved from promising to undeniable.

The next song, "Ages of You," carries with it a different kind of narrative weight, though no one in the club could guess it. It begins more modestly, another jangling figure from Buck, a steady beat from Berry. Stipe mumbles a quick introduction--if he names it at all, it is brief. To the audience, it is just another new song, a catchy one, with Mills' bass leaping out more boldly, his lines melodic enough to sing.

But the cameras are documenting something rarer. "Ages of You" had been intended for Chronic Town before label head Miles Copeland insisted they swap it out for "Wolves, Lower." It will not be officially released until five years later, on the odds‑and‑ends compilation Dead Letter Office in 1987. The tension here is archival rather than dramatic: this performance captures a song on the cusp of being set aside, shelved, and nearly forgotten. It exists in the setlist as a ghost of the EP that might have been.

On stage, of course, there is no sense of loss. Stipe sings it like any other, hips swaying, head bobbing. The chorus comes, and a few people up front start to move along, caught by the hook on first listen. Mills' voice wraps around Stipe's in harmonies that feel cheerier than some of the darker material earlier in the set. In the lens of the camera, this is just another moment of four guys pulling something out of themselves and sending it into the air of this cramped room.

When "Ages of You" ends, applause comes easily. Stipe steps back. Buck wipes sweat off his forehead with the back of his hand. Somewhere to the side, Mitch Easter can be glimpsed again, hovering at the edge of the stage, watching, perhaps reflecting on the alternate history where this song anchored Chronic Town instead of "Wolves, Lower."

The set now moves into its final arc. The mood in the room has changed subtly; the crowd is more vocal, shouting between songs, the band more relaxed, their earlier tension transmuted into momentum. The next song, "We Walk," drops the tempo slightly, a loping, almost hypnotic piece that will later sit on Murmur as one of its odd, dreamlike tracks. On this night, "We Walk" feels like a late‑evening stroll through a city's quieter streets, the club's colored lights dimming a notch, shadows lengthening along the walls.

Stipe uses more gestures here, pointing down an imaginary hallway as he sings, evoking images that, years later, fans will obsess over. At one point, he begins to talk‑sing, deviating from the recorded lyrics, telling a fragmented little story: "There's a marble table, it's made of glass… this girl walking out, she's got it pinned up to her shoulder…" His words tumble, half improvised, half recited from whatever stream of consciousness he is riding. "She looks into her own eyes, she looks into her lover's eyes, she looks… everyone eyes…" he continues, voice rising slightly, then lowers it to intone, "She sticks her finger to her head and slow it down… slow, keep it slow…"

The camera lingers on his face in this moment, the club reduced to a blur behind him. This is as close as the evening comes to a "monologue," but it is more incantation than exposition. There are no secrets revealed about the characters on stage; instead, we get a glimpse into how Stipe thinks on his feet, how he uses language as sound and image rather than straightforward storytelling. The crowd listens, maybe puzzled, maybe entranced, then cheers as the band eases back into the song's main groove.

As "We Walk" ends, the band is visibly looser. There is a sense--fleeting but real--that they could keep playing all night. But the set has a shape, and they are entering its final third. The lights shift slightly, maybe because the crew wants varied footage, maybe because the club's settings are being toyed with; either way, the stage gains a bit of extra drama, faces more starkly lit, sweat more reflective.

They launch into "Carnival of Sorts (Box Cars)," another Chronic Town song, and suddenly the club feels more like the inside of a moving train, rhythm steady, chords chiming like signals passing in the dark. Stipe's lyrics conjure images of boxes, cages, motion and confinement: "Don't get caught," he repeats, "creatures under…" The camera catches his hands miming the walls of a box, then snaps to Buck's fingers dancing across the fretboard, then to Mills, bobbing as he plays, his mouth open in wordless echo of the chorus.

The audience responds hooked by the song's rolling groove. Some sway, some hop in place, some mouth along words they've only half learned from the EP. The tension here is one of acceleration; we are clearly moving toward the end, but the band is not winding down. If anything, they are pushing harder, squeezing as much energy as they can into the time left before the lights come up and the spell breaks.

"Carnival of Sorts" stretches a bit, the band clearly enjoying riding its circular patterns. When it finally comes to its sharp end, Berry slams the final hit with extra force, cymbals shimmering. Stipe flashes another rare, quick smile and steps away from the mic, looking almost surprised to find himself still here after the emotional sprint of the set.

The crowd claps, cheers, maybe shouts for more. There is no scripted encore ritual, no leaving and returning; this is a club show, filmed for TV, and the band simply keeps going. The climactic final sequence begins with a groove that doesn't yet have a tidy song title in the band's catalog but will later be labeled by archivists and fans as "Skank."

It starts on a reggae‑tinged pulse, Mills' bass thumping a laid‑back pattern, Berry light on the snare, hi‑hat ticking like a clock in a different time zone. Buck shifts to a more rhythmic strum, letting notes hang and echo, his right hand looser, less bound to the martial precision of earlier songs. Stipe, no longer tethered to fixed verses and choruses, moves more freely, vocalizing, tossing off half‑phrases, letting melody drift in and out of speech.

The effect is immediate: the tension that has been building--the nervousness, the tight songs, the pressure to deliver--melts into a kind of exultant release. This is not a pop single to be played on radio; it is a band enjoying itself at the end of a hard‑driving set, stretching out into a jam for the simple joy of playing. The cameras capture Mills grinning openly now, head tipped back; Berry adding fills, rolling around the kit with more freedom; Buck occasionally closing his eyes, lost in the groove.

Stipe paces the small width of the stage, microphone cord trailing behind him like a tether. At times he sings coherent lines; at others he simply rides vowels over the music, body language becoming the main communication. The crowd, still packed in close, moves with them, an undulating mass under the low ceiling. In these final minutes, the Raleigh Underground feels like its own sealed universe, no outside world intruding, only this groove, this night, this band.

There are no deaths in this story, no villains emerging from the shadows, no secret crimes confessed under pressure. No one in the crowd collapses; no member storms off stage; no argument breaks out. Every "confrontation" has been musical: the band confronting its own songs, confronting the expectations carried by "Radio Free Europe," confronting the reality of being filmed, confronting the smallness of this room with the largeness of what they are building. Every one of those confrontations ends the same way: with the band playing through the tension and emerging tighter.

As "Skank" continues, it feels less like a "song" and more like a coda, a sustained emotional tone on which the whole night can drift out. The groove is relaxed but insistent, that reggae inflection turning the rhythmic screws just enough to keep heads nodding. Stipe's voice weaves in and out, occasionally dropping into near silence as the band carries the momentum, then rising again to throw another phrase into the air.

Finally, almost imperceptibly at first, Berry begins to wind things down. His fills point toward resolution rather than continuation. Mills simplifies his line, circling a root note, locking it down. Buck eases off the more ornate accents, letting chords ring only to cut them short. Stipe, sensing the shift, comes back to the mic stand, hands gripping it as though holding onto the last seconds of a dream.

The band tightens the loop one final time, Stipe riding the last few vocal lines out until the instant Berry decides it is over. With a collective, instinctive motion, they hit the last chord together and stop. The sound cuts, leaving only the echo of the room, the high whine of amps, and then the explosion of applause.

For a heartbeat, everyone is frozen. Stipe stands very still, chest heaving, staring down at the floor in front of the stage. Mills turns to Berry with a grin; Buck looks over the audience, taking in the small sea of faces that have just gone through this with them. Mitch Easter steps a little closer to the stage, maybe clapping, maybe calling out praise that the microphones do not clearly capture.

"Thanks," Stipe finally says into the mic, voice almost swallowed by the cheers. He might add the city's name--"Thank you, Raleigh"--or he might just nod and step back. There is no post‑credits scene, no revelation of hidden motives, no sudden twist that recontextualizes the night. The story has always been exactly what it appeared to be: four young musicians in a basement club in Raleigh, North Carolina, on October 10, 1982, playing a set of songs that map a crucial moment between obscurity and stardom.

One by one, they peel away from their instruments. Berry is first, standing from the drum stool, tossing his sticks onto the snare with a clatter and wiping his face on a towel. Mills unstraps his bass, gives the crowd a last wave, and steps off the small rise of the stage, disappearing into the shadows to the side. Buck carefully coils his cable, sets the Rickenbacker into its case or leans it safely against an amp, then follows. Stipe is last, still momentarily rooted to the spot where he has spent the last fifty minutes, hands in his hair, eyes on the ground, until he looks up, gives one quick, almost shy glance across the room, and turns away.

The cameras do not follow them backstage. There is no glimpse of celebratory toasts or exhausted arguments, no label exec waiting with a contract. The view stays on the stage as it empties, the amplifiers still humming quietly, the drum kit sitting silent, mics pointed at nothing. The audience sound fades under the closing credits or station identifiers that will later be added for TV; in the raw footage, it just bleeds into room tone and then tape hiss.

Outside, somewhere above this subterranean bar, the streets of Raleigh on that Sunday night in 1982 are ordinary: people going home, traffic lights cycling, nothing remarkable. Underground, something important just happened--important not because anyone died or secrets were exposed, but because a band that would come to define an era delivered a set that proved it could translate its nascent legend into live electricity, in front of a few hundred people and a handful of cameras.

There are no surviving on‑screen time stamps to tell us the exact hour, but by the time the last cable is unplugged and the last patron climbs the stairs to street level, it is late on October 10, 1982, and the world is unchanged and yet, in a tiny way, different. Somewhere far in the future, people will watch this on glowing screens and talk about how together they already were, how Michael Stipe seemed nervous and "too cool for school," how the band played like they had always belonged on stages larger than this. But in this story, the night simply ends.

No one dies. No one is unmasked. There are no hidden objects discovered, no confessions whispered into the mic beyond cryptic images of marble tables and glass and box cars and creatures under cages. The final resolution is more modest and more profound: the band finishes the last song, accepts the applause, and walks off. The tape keeps spinning for a few seconds longer, capturing amps buzzing in an emptying room. Then even that stops.

"R.E.M.: Live at the Raleigh Underground (1982)" ends exactly there: with silence reclaiming a small club in Raleigh after a fifty‑minute burst of sound on October 10, 1982, and the knowledge--available only in hindsight--that this was the earliest professionally filmed proof that R.E.M. could already do, live, what few bands ever manage at any point in their careers.

What is the ending?

The ending of R.E.M.: Live at the Raleigh Underground features the band delivering a powerful performance that resonates deeply with the audience. As the concert concludes, the energy in the room is palpable, leaving both the band and the fans in a state of exhilaration and connection. The film closes with the band members sharing a moment of camaraderie, reflecting on their journey and the impact of their music.

In a more detailed narrative, the ending unfolds as follows:

As the final notes of the last song echo through the dimly lit Raleigh Underground, the atmosphere is electric. The audience, a sea of faces illuminated by the flickering lights, sways and cheers, caught in the euphoria of the moment. The camera captures the raw emotion on the faces of the fans, their eyes wide with excitement and joy, as they revel in the music that has brought them together.

The band members--Michael Stipe, Peter Buck, Mike Mills, and Bill Berry--stand at the front of the stage, their expressions a mix of exhilaration and relief. They exchange glances, a silent acknowledgment of the hard work and dedication that has led them to this moment. Stipe, with his signature intensity, looks out into the crowd, his heart racing as he feels the connection with the audience. He knows that this performance is not just about the music; it's about the shared experience, the stories that each person carries with them.

As the last chord fades, the band takes a collective breath, soaking in the applause and cheers that wash over them like a wave. They bow, a gesture of gratitude towards the audience that has supported them. The camera zooms in on each member, capturing their individual reactions--Buck's smile, Mills' nod of appreciation, Berry's relaxed demeanor, and Stipe's contemplative gaze. Each of them is aware that this moment is a culmination of their journey, a testament to their passion and perseverance.

The lights begin to dim, but the energy in the room remains high. Fans chant for an encore, their voices rising in unison, a testament to the impact the band has had on them. The band huddles together, whispering and laughing, their camaraderie evident. They decide to return for one last song, a spontaneous choice that reflects their connection to the audience and their desire to give more.

As they step back onto the stage, the crowd erupts once again, a chorus of cheers and applause. The band launches into a final, spirited performance, pouring their hearts into every note. The camera captures the joy and passion radiating from the stage, the band members lost in the music, their movements fluid and energetic. The audience mirrors their enthusiasm, dancing and singing along, creating a vibrant tapestry of sound and emotion.

As the final song concludes, the band members exchange smiles, their faces glowing with the satisfaction of a job well done. They take one last bow, the connection between them and the audience palpable. The film closes with a lingering shot of the crowd, still buzzing with excitement, as the lights fade to black, leaving behind the echoes of the music and the memories of a night that will not soon be forgotten.

In this ending, each character finds fulfillment in their roles--Stipe as the passionate frontman, Buck as the creative force, Mills as the melodic anchor, and Berry as the steady heartbeat of the band. Their journey is marked by the joy of performance and the deep bond they share with their audience, encapsulating the essence of what it means to create and share music.

Is there a post-credit scene?

R.E.M.: Live at the Raleigh Underground, produced in 1982, does not contain a post-credit scene. The film primarily focuses on the live performance of the band, capturing the energy and atmosphere of their concert at the Raleigh Underground. The film concludes with the final notes of their set, leaving the audience immersed in the music and the moment without any additional scenes or content after the credits. The emphasis remains on the raw and authentic experience of the live show, reflecting the band's early days and their connection with the audience.

What songs are performed by R.E.M. during the concert in the film?

The film features a setlist that includes several of R.E.M.'s early hits, showcasing their energetic performance style and unique sound.

How does the band interact with the audience during the concert?

R.E.M. engages with the audience through direct eye contact, smiles, and moments of banter, creating an intimate atmosphere despite the larger venue.

What visual elements are prominent in the cinematography of the concert?

The cinematography captures the raw energy of the performance with close-ups of the band members, dynamic camera movements, and the vibrant lighting that enhances the mood of the concert.

How does Michael Stipe's stage presence contribute to the overall performance?

Michael Stipe's enigmatic stage presence, characterized by his expressive movements and emotive singing, draws the audience in and adds depth to the emotional experience of the concert.

What is the significance of the venue, the Raleigh Underground, in the context of the film?

The Raleigh Underground serves as a crucial backdrop that reflects the underground music scene of the early 1980s, emphasizing R.E.M.'s roots and connection to their local community.

Is this family friendly?

R.E.M.: Live at the Raleigh Underground is primarily a concert film showcasing the band's performance, and it is generally considered family-friendly. However, there are a few aspects that might be sensitive for children or more sensitive viewers:

-

Loud Music and Crowds: The concert atmosphere features loud music and a large, energetic crowd, which might be overwhelming for some children or those who are sensitive to noise.

-

Emotional Intensity: The performance includes moments of emotional intensity, both from the band and the audience, which could be impactful for younger viewers.

-

Visuals of a Live Performance: The film captures the raw energy of a live show, including close-ups of the band members and the audience's reactions, which may be intense but are not inherently objectionable.

Overall, while the film does not contain explicit content, the concert setting and emotional performances may evoke strong feelings that could be surprising for some viewers.