Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

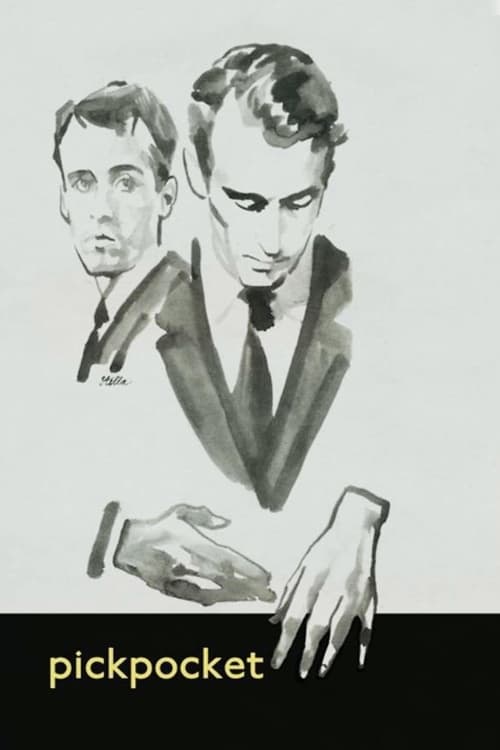

In the muted dawn of a Paris morning in 1959, the film opens with an intimate close-up: a hand pens words in a diary, the voice of Michel (Martin LaSalle) overlaying the scene with a confession, "Men who do these things keep silent; those who talk haven't done them. Yet, I have done them." This sets the tone of quiet alienation and internal turmoil that will pervade Michel's world. Alone in his sparse, dimly lit apartment, Michel is a young man unemployed, emotionally withdrawn, and adrift in a city that bustles around him but never truly touches him.

Michel's flat is a reflection of his inner desolation--a bare room with a door locked by a simple hook from the inside, symbolizing his self-imposed isolation. He writes in his diary, a private chronicle of his thoughts and justifications, while the city outside pulses with life. His relationship with his ailing mother is strained and distant; he avoids her, refusing to visit despite her worsening condition. The only connections he maintains are tenuous: Jeanne (Marika Green), a neighbor to his mother and lover of his friend Jacques (Pierre Leymarie), visits him with news of his mother's illness. Jeanne pleads gently, "Your mother is very ill, Michel. You should see her." But Michel shrugs off her concern, handing her money instead, a cold transaction that underscores his emotional detachment.

Jacques, Michel's sole friend, oscillates between frustration and loyalty. He tries to help Michel find work, offering him several jobs, but Michel dismisses them as beneath him. Jacques's skepticism is palpable, yet he remains a tether to the world Michel increasingly rejects. The tension between them is subtle but persistent, as Jacques senses Michel's descent into a life of petty crime.

The film's first major scene unfolds at the Longchamp Racecourse, a sprawling venue where the thrill of chance mirrors Michel's own reckless gambit. Here, Michel commits his first theft, deftly lifting money from a spectator's purse. The camera lingers on the stolen bills, symbolizing the seductive allure of crime. Yet, his triumph is short-lived; he is swiftly arrested by police officers who have been watching him. The arrest is not violent but inevitable, a moment of reckoning. At the police station, Michel faces the chief inspector (Jean Pélegrí), a man whose calm, penetrating gaze suggests he sees through Michel's facade. Their dialogue crackles with intellectual tension:

Michel, with a hint of arrogance, asserts, "Can we not admit that certain skilled men, gifted with intelligence, talent or even genius, and thus indispensable to society, rather than stagnate, should be free to disobey the laws in certain cases?"

The inspector counters, dryly, "Who will identify these supermen?"

Michel replies, "They themselves. Their conscience."

The inspector's skepticism is clear: "You know any man who doesn't think he's exceptional?"

Michel's confident reply, "Don't worry. It would only be at first. Then they'd stop," reveals his self-delusion.

The inspector warns, "They don't stop, believe me. A useful thief, then? A benefactor? That's the world upside down."

Michel's final retort, "It's already upside down. This could set it right," encapsulates his warped moral compass.

Despite the inspector's suspicions, Michel is released for lack of evidence, setting up a cat-and-mouse dynamic that threads through the film.

Michel's life spirals deeper into crime. At a bar, he meets Jacques and coincidentally encounters the inspector again. Here Michel's bravado surfaces; he subtly gloats about escaping arrest, his voice tinged with a dangerous mix of pride and defiance. He compares himself to Dostoyevsky's Raskolnikov, believing himself a superior man above ordinary laws.

Drawn inexplicably to the artistry of theft, Michel becomes fascinated by a master pickpocket he observes in the Paris Metro. The film choreographs these sequences with balletic precision--the nimble fingers, the fluid movements, the silent exchanges--turning theft into a perverse dance. Michel imitates the technique, initially succeeding and proudly declaring to Jacques, "I no longer need a job."

Yet, the thrill is fleeting. After a week, Michel is caught again, forced to lie low. He notices a mysterious man lurking outside his apartment--a fellow pickpocket who proposes a partnership. This encounter is charged with unspoken tension, the exchange of stolen wallets acting as a surrogate for human connection. The men's room confrontation between Michel and another pickpocket is a stark, intimate moment where money replaces intimacy, underscoring Michel's emotional void.

Meanwhile, Michel's mother's health deteriorates. Despite Jeanne's repeated urgings, Michel refuses to visit her, his avoidance steeped in a complex mix of guilt, shame, and arrogance. The mother's death occurs off-screen, a silent but pivotal event that deepens Michel's isolation and self-loathing. He neither witnesses nor participates in her final moments, compounding his emotional exile.

After the loss, Michel's detachment intensifies. He rejects the support of Jeanne and Jacques, retreating further into his criminal world. He travels briefly abroad--through Milan, Rome, and London--attempting to escape his past. Yet, these journeys are narrated briefly, emphasizing their futility; Michel cannot outrun his identity or guilt.

Back in Paris, the inspector continues his psychological pursuit. Their confrontations are subtle games of intellect and will rather than physical altercations. The inspector shows Michel an ingenious tool designed by a master pickpocket to slit coat pockets, blending admiration with accusation. Michel's response is a mixture of pride and challenge, as if daring the inspector to catch him.

Michel's relationship with Jeanne remains fraught but vital. Jeanne embodies hope and redemption, her unwavering faith in Michel's capacity for change a stark contrast to his self-imposed exile. Their interactions are quiet confrontations; Jeanne's gentle persistence meets Michel's cold resistance. Yet, she remains a beacon, refusing to abandon him.

The climax arrives as Michel, after years of drifting and petty crime, surrenders to the inevitable. Arrested once more, he faces imprisonment. In the stark confines of his cell, the film's emotional core unfolds. Jeanne visits him, tending to his mother's grave and standing steadfast beside him. In a rare moment of vulnerability, Michel confesses, "I have done these things. I cannot connect with others. I am lost."

Jeanne offers no judgment, only forgiveness and love. Their embrace through the prison bars is a powerful visual metaphor for connection achieved through suffering and humility. Michel's voice-over closes the film with a note of fragile hope: "Oh, Jeanne, to reach you at last, what a strange path I had to take."

The film ends on this intimate, redemptive note, underscoring its central themes of guilt, alienation, and the possibility of grace even for the most isolated souls. Michel's journey from silent thief to a man touched by love and forgiveness is a testament to the human capacity for change, rendered with Robert Bresson's meticulous minimalism and profound emotional insight.

What is the ending?

In the ending of "Pickpocket," Michel, the protagonist, is arrested after a failed pickpocketing attempt. He is confronted by the police and ultimately faces the consequences of his actions. In the final moments, he reflects on his life choices and the emptiness of his pursuits. The film concludes with a sense of ambiguity regarding his future.

As the film approaches its conclusion, the tension builds around Michel, the young pickpocket who has been navigating the streets of Paris with a mix of skill and reckless abandon. The scene opens with Michel in a crowded train station, his heart racing as he prepares for another theft. He is acutely aware of the thrill that comes with the act, yet there is an underlying sense of dread that looms over him. The camera captures his furtive glances and the way his fingers twitch with anticipation, revealing his internal conflict between the exhilaration of his criminal life and the moral implications of his actions.

In a pivotal moment, Michel attempts to pickpocket a man in a bustling crowd. The scene is frenetic, filled with the sounds of rushing feet and the chatter of commuters. As he deftly reaches for the man's wallet, he is suddenly caught in the act. The man turns, and in a swift motion, he alerts the nearby police. Michel's heart sinks as he realizes he has been discovered. The camera zooms in on his face, capturing the panic and desperation that wash over him.

The police quickly surround Michel, and he is apprehended. The scene shifts to a stark interrogation room where he sits alone, the harsh fluorescent lights casting shadows on his face. He is questioned about his actions, but Michel remains defiant, struggling to articulate the motivations behind his choices. The internal turmoil is palpable; he grapples with feelings of shame and a longing for freedom, yet he cannot fully abandon the thrill of his lifestyle.

As the narrative unfolds, we see flashbacks of Michel's life, interspersed with his current predicament. These moments reveal his relationships with other characters, such as his mother, who has been worried about him, and his love interest, Jeanne, who represents a life of normalcy that he cannot seem to grasp. The juxtaposition of these memories against his current situation highlights the stark contrast between the life he leads and the life he yearns for.

In the final scenes, Michel is taken away by the police, and the weight of his choices settles heavily upon him. He walks through the station, handcuffed, as the bustling crowd continues around him, oblivious to his plight. The camera captures the isolation he feels, even in a sea of people. His expression is one of resignation, a man who has chased the thrill of pickpocketing only to find himself trapped by the very life he chose.

The film concludes with a lingering shot of Michel's face, reflecting a mix of regret and acceptance. He understands that his actions have led him to this moment, and as he is led away, there is a sense of ambiguity about his future. Will he find redemption, or will he remain trapped in the cycle of crime? The ending leaves viewers with a haunting question about the nature of choice and consequence, encapsulating the essence of Michel's journey throughout the film.

Is there a post-credit scene?

The movie "Pickpocket," directed by Robert Bresson and released in 1959, does not contain a post-credit scene. The film concludes with a poignant and introspective ending that encapsulates the protagonist's journey and emotional state. After a series of events that lead to his arrest and subsequent release, Michel, the main character, reflects on his life choices and the nature of his existence. The film ends on a note of ambiguity, leaving the audience to ponder Michel's future without any additional scenes or credits that extend the narrative. The focus remains on the themes of guilt, redemption, and the search for meaning, which are central to the film's exploration of the human condition.

What motivates Michel to become a pickpocket?

Michel, the protagonist, is driven by a complex mix of existential curiosity and a desire for freedom. He feels a deep sense of alienation from society and is drawn to the thrill of stealing as a way to assert his independence and challenge societal norms. His fascination with the art of pickpocketing is also fueled by a desire to prove himself and to find a sense of purpose in a world that feels meaningless to him.

How does Michel's relationship with his mother influence his actions?

Michel's relationship with his mother is strained and filled with tension. She disapproves of his lifestyle and is worried about his future, which adds to his feelings of isolation. Her disappointment serves as a haunting reminder of the life he could have led, and this conflict drives him further into the world of crime as he seeks to escape her expectations and societal norms.

What role does the character of Jacques play in Michel's life?

Jacques serves as both a mentor and a rival to Michel. He introduces Michel to the world of pickpocketing and teaches him the techniques of the trade. However, Jacques also embodies the darker side of this lifestyle, as he is manipulative and self-serving. Their relationship is complex; while Jacques encourages Michel's criminal pursuits, he also represents the moral ambiguity and potential consequences of that life.

How does Michel's relationship with Jeanne develop throughout the film?

Jeanne is a significant figure in Michel's life, representing a potential for love and redemption. Initially, Michel is emotionally distant and struggles to connect with her due to his obsession with pickpocketing. However, as the story progresses, Jeanne becomes a source of hope for him, and their relationship deepens. Michel's feelings for her conflict with his criminal lifestyle, ultimately leading to moments of introspection about his choices.

What is the significance of the final scene between Michel and the police?

The final scene is pivotal as it encapsulates Michel's internal struggle and the consequences of his actions. When confronted by the police, Michel experiences a moment of clarity and acceptance of his fate. This confrontation serves as a culmination of his journey, highlighting the tension between his desire for freedom and the inevitable repercussions of his criminal life. It is a moment of both defeat and liberation, as he faces the reality of his choices.

Is this family friendly?

"Pickpocket," directed by Robert Bresson in 1959, is not typically considered family-friendly due to its themes and content. Here are some potentially objectionable or upsetting aspects:

-

Crime and Theft: The film revolves around pickpocketing, showcasing the protagonist's involvement in theft, which may not be suitable for younger audiences.

-

Moral Ambiguity: The main character, Michel, struggles with his moral choices, leading to a complex exploration of guilt and existentialism that may be difficult for children to understand.

-

Isolation and Loneliness: Michel's emotional state is marked by feelings of isolation and detachment, which could be unsettling for sensitive viewers.

-

Confrontations with Authority: There are scenes involving police and confrontations that may evoke tension or anxiety.

-

Emotional Turmoil: The film delves into themes of despair and internal conflict, which may be heavy for younger viewers or those sensitive to such topics.

Overall, the film's exploration of darker themes and the psychological depth of its characters may not resonate well with children or those looking for lighthearted content.