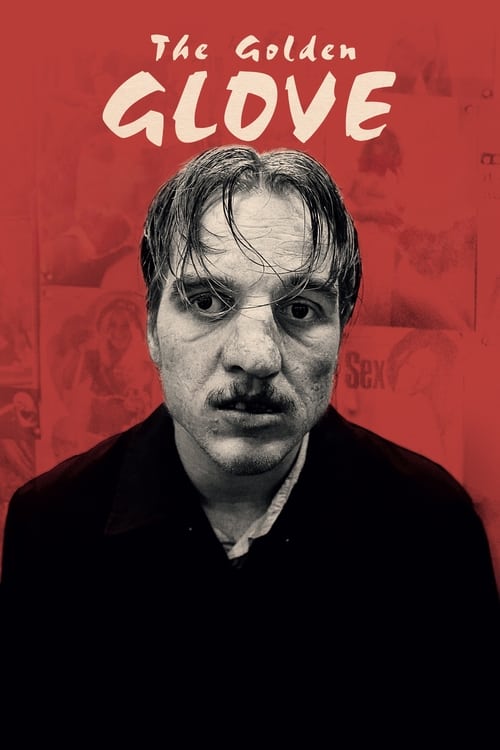

Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

Hamburg, St. Pauli, 1970.

In the cramped attic of a tenement house, the night is thick with cigarette smoke and the sour reek of sweat, cheap liquor, and something that already smells like rot. A bare bulb hangs from the ceiling, casting a yellow cone of light over a narrow bed with stained sheets, over piles of clothing, porn magazines thumbed to rags, empty bottles rolling underfoot. Fritz Honka stands there in his undershirt, his crooked nose and ruined face glistening with sweat, his breath coming in low, exhausted grunts.

On the floor lies Gertraud Bräuer.

She is already dead when we meet her, a bloated, middle‑aged prostitute whose body is slack and heavy, limbs twisted where she fell. Her eyes stare at nothing. Fritz works over her mechanically, half drunk, half blank, as if he is just finishing a chore he started in a blackout. The camera stays with him as he strips her clothes, revealing mottled skin, bruises, folds of flesh. There is no music, only the scrape of metal, the rasp of his breath, the wet sounds as he begins to cut.

He saws and hacks at her limbs, the small attic filled with the wet slap of a knife against bone and tendon. He curses under his breath when he slips, when blood runs onto his hands. He is not efficient or practiced, only desperate and clumsy. He mutters to himself in rough Hamburg slang, voice thick with booze: "Scheißweib… always screaming… shut up now, eh?" He quarters Gertraud's body, piece by piece, in an unblinking, almost clinical tableau of butchery.

He drags out an old, battered suitcase from under the bed, flips it open, and begins to pack parts of her inside: a leg folded awkwardly at the knee, an arm jammed in diagonally. The case is too small; he pushes, grunts, wipes his brow with the back of his bloody forearm. The zipper resists the swollen flesh. He forces it closed, the teeth straining.

What does not fit goes somewhere else.

He climbs up on a rickety chair, wobbling, reaches with bloody fingers to a warped panel in the ceiling where the wall and roof meet. He has done this before: he knows exactly which nail to pry up, where the plaster gives. Behind the loose board, a narrow void opens, dark and dusty. He stuffs wrapped bundles into the space, wrapping them in rags, newspaper, plastic. Flesh slides against wood. The attic's air grows heavier.

He lowers the panel, taps it roughly back into place, and steps down. The room is a disaster: blood stains on the floor, on the mattress, on his hands. He stares at his fingers as if they belong to someone else. Then he shrugs, picks up a rag, smears more than he cleans, and finally collapses onto the bed, face turned toward the wall porn, as if their frozen bodies could distract him from the real one he has just destroyed.

Later, offscreen, a suitcase is found. Somewhere in Hamburg, police open the battered case and recoil at the stench. Gertraud Bräuer's dismembered remains stare up at them, anonymous, unclaimed. No one knows her name, or his. They cannot identify the killer. The case is filed as a gruesome curiosity, a mystery that will fade under newer headlines.

The film leaves the detectives behind. It does not care about them. It cares about the bar.

"Zum Goldenen Handschuh" – The Golden Glove – glows like a greasy wound in the night of St. Pauli's Reeperbahn, the red‑light district near the harbor. Outside, neon flickers in sickly colors over wet cobblestones. Inside, everything is brown: nicotine‑stained walls, worn wood tables, cigarette smoke hanging in layers. Schlager songs, sentimental German ballads, pour from the jukebox, the tinny speakers giving them a warped melancholy. Old drunks sing along, their eyes shining with tears that might be from memory or from booze.

Fritz Honka is at home here.

He shuffles in, shoulders rounded, head bobbing slightly as if apologizing for existing. His face, already grotesque, seems exaggerated in this light: the broken nose, the crooked teeth, the scarred, ratlike features that make him look like a caricature of himself. He takes his usual place at the bar, mumbling a greeting. The bartender barely nods. This is a place where everyone is both regular and invisible.

Around him sit the others: washed‑up prostitutes whose makeup is a smear of better days; old men in worn jackets, their hands shaking around shot glasses; women whose lipstick balances on the cracked border of their yellowed teeth. Among them is Hertha, sharp‑tongued and weary. She sways on her stool, raising a glass, and delivers one of the bar's bitter proverbs to no one in particular: "Pride goes before a fall. I'm telling you. Be friendly on your way up. Because on your way down, you're gonna meet them all again. And they all come down sometime."

Laughter bubbles up, then dissolves into coughing.

Fritz drinks schnapps and beer, chaser after chaser, his eyes always roaming, seeking that specific kind of woman: older, alone, already numbed. He leans close, breath rancid, making offers. "I got a place," he says, again and again. "Warm. You don't have to sleep in the shelter. I'll treat you nice." He is pitiful, not charismatic, but hunger – for warmth, for tenderness, for just another drink – makes some women listen.

Nights blur. He returns to his attic apartment, always. Sometimes alone, sometimes with a woman whose face might as well be Gertraud's. The film refuses to make a neat schedule of his killings. It lets us feel the repetition, the drift of time. The hidden void in the ceiling grows heavier, more foul, a secret not even he wants to look at too closely.

Then comes Gerda, a fragile presence in his life, then gone. Summaries mention her departure – "With Gerda gone, Fritz approaches three alcoholic women: Inge, Herta, and Anna." The film suggests that whatever small, pathetic semblance of companionship she provided has vanished. The loss leaves him even more unmoored.

One night, after too many drinks at the Golden Glove, a fight erupts. The bar is always on the edge of violence: a shove near the jukebox, an insult over a spilled drink, a slap that lands too hard. Voices rise, the bartender bangs on the counter, shouting for calm. In the chaos, Fritz finds an opening. He turns to three women who orbit the bar like exhausted planets: Inge, Herta, and Anna.

Inge is the most alert, eyes hard behind smudged eyeliner. Herta is heavier, her face sagging, half melted by years of drink. Anna is already close to unconsciousness, her head bobbing with each heartbeat, a cigarette burning down between her fingers.

"Come with me," Fritz urges, using the bar fight as pretext. "It's no good here tonight. I got schnapps at home. A bed. We can have a good time." His words clump together, but the meaning is clear enough. They hesitate, then nod. What else is there? The Golden Glove is only warm until the door closes behind them.

They step out into the Hamburg night, St. Pauli's neon reflected in puddles of last week's rain and urine. The harbor air is cold, smelling of diesel and fish. As they walk, Herta begins to lag. Her knees buckle. She laughs weakly, then crumples, collapsing on the street like a sack of rags. Inge and Fritz halt; Anna stares, barely conscious.

"Get up," Fritz slurs, nudging Herta with his foot. She groans, tries, fails. He glances around: no one is watching. No one ever is. He shrugs.

"Leave her," he says. "She'll sleep it off." Inge looks down at Herta, lying there on the cold pavement, then at Fritz's expectant face. For a moment there is a flicker of resistance, a ghost of solidarity. It dies quickly. She is too tired to argue. They leave Herta on the street, abandoned, a living piece of trash, and move on.

By the time they climb the stairs to Fritz's attic, Anna is shuffling blindly, one hand trailing along the peeling wall. The smell hits Inge first: a dense, sour fog pouring from under his door. It is worse inside.

The apartment is a cave of filth. Bottles everywhere, stacks of newspapers, food rotting on plates and in jars. On one shelf, a jar of pickled sausages wears a coat of white mold so thick it looks like fur. The walls are papered with pornographic images, torn from magazines and pasted in uneven rows, naked bodies lit by the same yellow bulb that makes the room's stains glow. The air is damp, heavy with something that is not quite recognizable but instinctively repulsive. Inge wrinkles her nose.

"What's that smell?" she asks, half joking, half horrified.

"From the drains," Fritz snaps quickly. "Old house. Rats. You get used to it." He waves them toward the bed as if they are guests he's proud to host.

He pours schnapps into cloudy glasses, the liquid slopping over. Anna drinks automatically, eyes unfocused. Inge sips, eyes scanning the room. Anxiety prickles along her spine. Fritz sits on the edge of the bed, watching them.

Then he makes his request.

"You two," he says, pointing from one to the other. "Do it. Lick each other. I want to see it. Do it." His tone is aggressive, not pleading; under the booze there's a demand for power.

Inge stares at him. "What?" she says, laughing incredulously.

"You heard me." He leans forward, eyes gleaming. "Go on. Take off your things. Use your tongues. I want to see."

Anna is too drunk to respond coherently. Her head lolls. She mumbles something unintelligible, then giggles. Inge's laughter turns hard.

"No," she says. "I'm not doing that. We didn't come here for that."

Fritz's face tightens. His wounded pride rises like bile. "You think you're too good? You're all the same. Sitting in that bar, all high and mighty, but you'll spread your legs for a drink. You do what I say."

"I said no," Inge repeats, louder. "You're disgusting. This place stinks. I'm leaving."

She stands up. Fritz moves faster than his drunken wobble suggests he can. He grabs her arm, fingers digging into flesh. "You're not going anywhere," he snarls. "You owe me." He yanks her back, shoving her toward the bed.

She fights him. They stumble. He slaps her, once, twice, the sound sharp in the small room. She cries out. He pushes her down, kneeling on her. For a moment, it looks as if he might do what he intended to do to both women anyway, by force.

But Inge is sober enough, angry enough. She scratches his face, nails digging into his skin. He recoils with a howl, hands flying to his cheek. She uses the moment to twist away, scramble to her feet. She heads for the door, knocking over bottles, sending them rolling and smashing.

"Bitch!" Fritz screams. "You come back here!"

She is already in the hall, pounding down the stairs, the sound of her footsteps fading into the building's muffled night. She escapes. She lives.

Fritz is left with Anna.

He turns back. Anna is still on the bed, slumped against the wall, half conscious, drool on her chin. She has not even fully registered what just happened. Her eyes flutter open lazily.

"You," Fritz says, pointing at her, breathing heavily. "You'll do it."

She blinks, incomprehension swimming in her gaze. "What?" she whispers.

"Get on your knees," he orders. "Do what I say."

She doesn't move. The refusal is not defiance; it is incapacity. She is simply too drunk, too far gone. She giggles again, a small bubbling laugh that may be her last carefree sound.

Something snaps in him. The humiliation from Inge's escape, from her refusal, from her implied judgment of his smell, his filth, his worthlessness, pours into him like gasoline. He grabs Anna by the hair and drags her off the bed. She yelps, suddenly more awake, struggling weakly.

He slams her head against the edge of the table.

The first impact makes a dull, wet thud. Anna cries out. He does it again, harder. Blood begins to smear along the wood. Again. Again. He roars with each blow, spitting: "Do what I say! Do what I say!" The table shudders. Her skull yields. Her voice disappears, replaced by a thick silence broken only by the repeated crack of bone against wood.

At last he lets go. Anna slumps to the floor, head at an unnatural angle, blood pooling around her. Her chest does not rise. Her eyes stare past him at the porn on the wall.

He stands over her, panting. His hands shake. Then he sighs, puts his hands on his knees, and bends down to get to work.

The dismemberment of Anna echoes Gertraud's: methodical, clumsy, obscene. He quarters her, wraps parts in rags and newspaper, stuffs them into the now‑familiar void in the wall and ceiling. The hidden locker grows heavier. The apartment's smell deepens to a permanent, oily stink that clings to everything.

Days turn into nights, nights into the same bar, the same drinks. At some point – the film's chronology is intentionally blurry, but the key incident is clear – Fritz leaves his apartment in the morning still drunk, the alcohol and the weight of his hidden atrocities making him stagger as he passes through St. Pauli's streets. The city is waking up: trucks rumbling, market stalls opening, the harbor cranes skeletal against the gray sky.

He steps into the road without looking.

A van screeches, too late. It slams into him. His body spins, crashes onto the pavement. For a moment, he lies there, stunned, staring up at the washed‑out sky. People gather. Voices shout. An ambulance siren wails in the distance.

Fritz survives. Bruised, battered, shaken. The impact knocks something loose: not his murderous drive, but his drinking – for a while. He recovers sufficiently to limp back to the Golden Glove, to sit at the bar one last time before a temporary abstinence. He looks at the glasses lined up on the shelf, the familiar bottles, the men and women who have been his only companions. A kind of grim decision hardens in his face.

"Enough," he mutters to himself. "No more booze. It's killing me."

From then on, he remains sober – for months, perhaps longer. The film compresses this period but marks it clearly: no more drinking scenes, no more stumbling in late. Instead, Fritz tries to become something like a normal working man. He finds employment as a night watchman at a modern office complex, far from the fetid confines of his tenement.

The office building is all glass and clean lines, polished floors and fluorescent lights. At night it is quiet, emptied of daytime bustle, the ticking of clocks echoing in long hallways. Fritz patrols the corridors in a uniform, keys jangling at his belt. Cameras watch him. The silence is a different kind of oppressive.

Here he meets Helga Denningsen.

Helga is a cleaner, moving methodically from office to office, dusting desks, emptying wastebaskets, wiping away the day's traces of respectable labor. She is not like the women in the Golden Glove: younger, tidier, still anchored to some semblance of routine. Her face is plain but open. She smiles politely when she bumps into him.

"Evening," she says the first time, pushing a cart full of cleaning supplies.

He nods, shy. "Evening," he replies.

He begins to time his rounds to coincide with hers. They exchange small talk: comments about the building's temperature, the stupidity of the bosses who leave lights on, the quiet. Fritz watches her from the corner of his eye, imagines what it would be like to have her in his life. Not as a prostitute, not as a body to be used and discarded, but as something else: a girlfriend, a wife, someone who might cook for him, share his bed without him paying.

He fantasizes. He pictures bringing Helga to his apartment, but even in his imagination, the thought falters when it reaches the reality of that room: the stench, the hidden corpses. He never invites her. His isolation, his shame, his secret, all conspire to keep her at a distance.

This interlude of sobriety and possibility is brief, fragile, and ultimately meaningless. The film shows Fritz awkwardly trying to talk to Helga, perhaps mustering the courage to ask her out, then failing, his tongue heavy, his self‑disgust stronger than his desire. He remains alone. His night shifts stretch on, monotonous. The Golden Glove's call grows louder in his memory.

Eventually, he breaks.

One night, or maybe late afternoon, he returns to St. Pauli. The neon is the same; the songs are the same; the barstools are in the same places. He walks back into the Golden Glove as if he never left. No one applauds his return. The regulars barely glance up. They have their own battles with sobriety, most of them long lost.

He orders a drink. The glass is cold in his hand, the schnapps clear and merciless. He stares at it for a second, then tips it back. The burn down his throat is like an old friend returning. One becomes two, then three.

Soon he is back to his old rhythm: drinking heavily, scanning the room, looking for women who can be persuaded to follow him home. The brief window in which he might have gone a different way closes without fanfare. The office complex, Helga, the uniform – they recede into the background of his personal history, a failed attempt at normalcy.

Now he finds Frida.

Frida is a prostitute, like Gertraud, like Ruth who will come later. She is not young; her face bears the lines of years spent in smoky bars and on cold streets. But she is quick with a joke, still capable of mocking the men who pay her. Fritz watches her, drunk and needy, his eyes bright.

He approaches. "Come with me," he offers, the same words as always. "I'll pay. I got a place."

She sizes him up. A loser, but a paying loser. She shrugs. "All right. Let's go."

They leave the Golden Glove, stepping into the night's damp chill. Back at his apartment, the smell now is apocalyptic. The hidden corpses in the wall – Gertraud, Anna, and perhaps others the film implies but does not fully enumerate – have been rotting for months, maybe years. Neighbors have complained. They've speculated about dead rats, blocked drains, his hoarding. They gag in the hallway but do not push the door open.

Frida wrinkles her nose the moment she steps inside. "Jesus, what died in here?" she says, half joking, half angry.

"Rats," Fritz answers automatically. "Pipe problem. Sit down."

She drops her bag on the bed, takes in the porn, the filth, the bottles. This is not unusual in her line of work, but the intensity here is special. She decides not to care, at least not enough to walk out.

They undress. Fritz tries to have sex, but something in him fails. He can't maintain an erection. Frida, impatient, rolls her eyes. "Come on, what's this?" she says. "You drag me here for this?" She laughs, a short, sharp bark that slices into his fragile pride.

He flushes. He hits her, a quick slap, trying to reassert control. She swears, shoves him back. The encounter is already turning sour. Eventually, exhausted, he passes out, sprawled across the bed, leaving her awake, irritated, and opportunistic.

Frida looks around. The apartment is squalid, but there must be something of value somewhere. She begins to move quietly, rummaging through drawers, pockets, under the mattress. She finds some money, maybe a watch, small items she can slip into her bag. Her eyes land on the jar of spicy mustard in the kitchen area.

A wicked idea surfaces. She pads back to the bed, where Fritz lies snoring, genitals exposed. She unscrews the mustard jar. The smell is sharp, pungent. She scoops some out and smears it onto his penis and testicles, coating him thoroughly. She grins, a small revenge for his slap and his pathetic performance.

Then she keeps searching, stuffing more of his things into her bag.

The mustard begins to burn. At first, it tickles his skin in his sleep. Then the burn intensifies, like acid. Fritz's face contorts. He wakes with a strangled scream, hands flying to his crotch. He howls, flailing on the bed, eyes wild.

Frida bursts out laughing. "Serves you right!" she cackles. "Can't get it up, but you feel that, eh?" She punctuates her mockery with a kick to his groin, hard, adding a new layer of pain.

His scream changes pitch. Humiliation, physical agony, and the feeling of being mocked, robbed, and violated all fuse into volcanic rage. He lunges at her. The small room becomes a pinball machine of bodies and objects: they crash into the table, the bed, the walls. Bottles fall and smash. Their struggle is ugly, desperate.

"Give it back!" he roars, grabbing at her bag, at her hair, at whatever he can get his hands on.

"Pig!" she spits. "You're nothing! Look at you, living in this shit hole!"

He slaps her, punches her. She claws his face, leaving bloody streaks. He gets his arms around her throat. She jerks, gasping. He squeezes. The sound of her voice is cut off mid‑insult. Her elbows slam into his ribs, but his grip tightens.

He strangles her, eyes bulging, teeth bared. The room fills with the ragged sound of his breathing and the small, choking noises she makes as her air is cut off. He slams her against the floor, battering her. At some point, the line between self‑defense and murderous frenzy is obliterated. He continues after she is limp, his hands still around her neck, as if squeezing the life from her one more time.

Frida dies there, on his floor, neck bruised, face mottled, one hand still clutching the strap of her bag. He lets her go, panting. The smell of mustard and sweat and old rot mingles into a nauseating fog.

Then, as before, he cleans up in the only way he knows. He quarters her, dismembers her body with the same dull tools, wraps the parts, stuffs them into the wall and ceiling void with the others. The hidden cavity is now crammed with death, a boneyard pressing outward against the flimsy plaster.

In the following days, he lures Ruth.

Ruth is another prostitute from the Golden Glove, another woman living on the edge of survival. The film's summaries do not detail every moment of their interaction, but the pattern is familiar: he meets her at the bar, buys her drinks, offers shelter, money, a bed. She sees a client, nothing more, and agrees to accompany him to his apartment.

The same hallway, the same stench, the same porn on the walls. Maybe she comments on the smell; maybe she doesn't. They attempt sex. His impotence, his anger, his resentment at being laughed at and treated as pathetic all swirls around them. A confrontation arises – a harsh word, a rejection, perhaps a laugh at his failure, as with Frida. The film shows, more than explains, the escalation.

He kills her.

Like Frida, like Anna, like Gertraud before them, Ruth dies in that attic, murdered by Fritz Honka's hands. Whether he strangles, beats, or cuts her is less important to Akin than the fact of her death and the sameness of his brutality. He dismembers her as well, quartering her and placing her remains in the already overcrowded void between wall and roof. The board goes back, the darkness swallows her.

The murders, at least the explicitly shown ones, are done. The film has followed the four known victims between 1970 and the mid‑1970s: Gertraud Bräuer, Anna, Frida, and Ruth, all killed by Fritz Honka in his apartment, all dismembered, hidden. The Golden Glove continues, oblivious. Its regulars still drink, sing, complain. Honka still comes in, still drinks, still rants about not getting laid, sometimes babbling about a younger girl he fixates on from afar. The world turns, indifferent.

The stench, however, no longer can be ignored.

Neighbors in the tenement complain repeatedly. The smell seeps into the hallway, into other apartments, slipping under doors like a poisonous fog. People bang on his door, shouting, "Honka! Clean your place! It stinks!" He shouts back that it's the drains, the building, the rats. The landlord grumbles, threatens eviction, maybe calls a plumber who shrugs and blames the old pipes. No one imagines what is really behind the wall.

The film does not introduce a heroic detective, no procedural montage of evidence gathering and forensic brilliance. It refuses that comfort. These women are too far down the social ladder; their disappearances barely register. They are missed by no one with power. There is no one out there hunting Fritz, no one who even knows there is a hunt to be had.

What ends his killings is not conscience, nor police work, but accident – again.

One day, a fire breaks out in the building. The exact cause is not dwelt upon: a cigarette left burning, an overloaded circuit, a stove left on; in a tenement like this, any spark can turn into an inferno. Smoke snakes under doors, thick and black. Residents scream, clatter down the stairs. Sirens wail, louder this time, closer.

Firefighters arrive, axes and hoses at the ready. They force open doors, shout into rooms, search for trapped people. When they reach the top floor, the smoke is thickest. They smash Fritz Honka's door open.

The moment they step inside, they gag.

The heat and flames have only intensified the smell that has been building in this space for years. It is not just smoke; it is the sweet, sickly, unmistakable stench of long‑decayed human flesh. The firefighters, used to many horrors, stagger.

They move through the cramped room, their flashlights cutting through smoke to reveal porn peeling from the walls, bottles everywhere, the mattress half burned. They search for bodies, expecting to find someone overcome by smoke. They find something else.

One of them notices the warped panel near the ceiling, slightly ajar now from heat and structural shift. The smell is strongest there. He climbs onto a chair, coughs, and pries at the board with his gloved hands. It gives way with a crack, falling inward.

Behind it is not empty space but a mass of wrapped bundles, bones protruding, flesh slipped from them in strings. Skulls stare down, eye sockets black, hair still clinging to some, jawbones clenched. Maggots spill out, falling in clumps, a pale rain. The firefighters recoil, swearing.

Police arrive. The apartment becomes a crime scene. Photographers' flashes punctuate the gloom. Officers in suits and uniforms move gingerly, picking their way through the debris, holding handkerchiefs to their noses. They inventory: multiple sets of remains, stuffed into the wall and ceiling. The improvised locker yields Gertraud Bräuer, Anna, Frida, Ruth – four women, four lives reduced to anonymous limbs until the forensic work matches them to missing persons.

The confrontation that follows is not dramatic in a cinematic, action‑movie way. There is no chase across rooftops, no standoff with guns drawn. Fritz Honka, the man who fancied himself invisible, is confronted not by a single heroic figure but by the weight of reality and law.

He is arrested.

The film does not linger on the arrest or the courtroom; it is not interested in giving him a glamorous final act. It may show police taking him away, his body shrunken, his face bewildered, as if he cannot understand how his private kingdom of filth has suddenly become public. The regulars at the Golden Glove, hearing the news, might react with shrugs, disbelief, morbid fascination. "Honka? That little rat? A killer?" they might say. Then they order another round. Life in St. Pauli goes on.

There is no redemption, no introspective confession that offers insight into his psyche. As Roger Ebert's review notes, Akin avoids the tropes that paint serial killers as troubled geniuses or tortured souls. Fritz is shown as what he is: a mentally deficient, alcoholic loser who found in murder a hideous, pointless outlet for his frustrations. His victims are shown as what they are: lonely, destitute women whose lives and deaths barely ripple the surface of the city.

The final images pull back further from fiction.

As the story ends, the film's closing credits roll over black‑and‑white photographs: the real Fritz Honka, the real women he killed, the real Golden Glove bar, the real weapons he used. Their faces are not actors' faces now but those of people who once sat in that bar, walked those streets, climbed those stairs. The photos connect the recreated, stylized atrocity we have just witnessed with the historical case on which it is based: four women murdered between 1970 and 1974 in Hamburg, their bodies hidden in the attic apartment of a man no one wanted to see.

There is no coda telling us what became of Fritz in prison, no comforting statistics about lessons learned or systems improved. The film ends as it began: immersed in ugliness, refusing to look away, insisting that these deaths – Gertraud Bräuer, Anna, Frida, Ruth, all killed by Fritz Honka – were not the work of a glamorous monster, but of a small, pathetic man in a filthy room, in a city that barely noticed until the smell of his crimes set the building on fire.

What is the ending?

In the ending of "The Golden Glove," the protagonist, Fritz Honka, is ultimately apprehended by the police after a series of brutal murders. The film concludes with his arrest, showcasing the grim reality of his life and the consequences of his violent actions.

As the film approaches its climax, we find Fritz Honka, a disheveled and disturbed man, continuing his grim routine in the seedy underbelly of Hamburg during the 1970s. The atmosphere is thick with despair, and the dingy bar, The Golden Glove, serves as a backdrop for his increasingly violent tendencies.

Scene by scene, the tension escalates. Fritz, portrayed with a haunting intensity, is shown luring vulnerable women from the bar, often those who are intoxicated or desperate. His interactions are marked by a mix of charm and menace, revealing his internal struggle between a desire for connection and his darker impulses.

In one pivotal scene, Fritz invites a woman back to his apartment, where the atmosphere shifts dramatically. The dim lighting casts shadows across the room, amplifying the sense of dread. As the woman begins to realize the danger she is in, Fritz's demeanor changes from seemingly benign to violently aggressive. The camera captures the raw horror of the moment, emphasizing the brutality of his actions as he murders her in a fit of rage.

Following this, the film depicts Fritz's attempts to dispose of the bodies, showcasing his frantic and desperate state of mind. He is shown dismembering the corpses, a gruesome task that he approaches with a chilling detachment. The visceral imagery serves to highlight his complete moral decay and the depths of his depravity.

As the police begin to close in on him, the tension mounts. Fritz's paranoia grows, and he becomes increasingly erratic. In a haunting sequence, he is seen wandering the streets, his disheveled appearance a stark contrast to the vibrant nightlife around him. The juxtaposition of his internal chaos against the backdrop of a bustling city underscores his isolation and the consequences of his actions.

The climax reaches its peak when the police finally catch up to Fritz. In a tense confrontation, they arrest him, and the weight of his crimes comes crashing down. The film captures the moment with a stark realism, showing Fritz's blank expression as he is led away in handcuffs, a man broken by his own monstrous behavior.

In the final scenes, the narrative shifts to a broader view of the aftermath. The film closes with a sense of bleak inevitability, reflecting on the lives lost and the darkness that enveloped Fritz. The fate of the women he murdered is left hauntingly unresolved, their stories cut short by his violence. Fritz's arrest serves as a grim reminder of the consequences of unchecked rage and the tragic cycle of violence that permeates the world he inhabits.

Ultimately, "The Golden Glove" ends on a note of despair, encapsulating the tragic fate of its characters and the dark realities of human nature. Fritz Honka is left to face the repercussions of his actions, a chilling testament to the depths of his depravity and the lives he irrevocably shattered.

Is there a post-credit scene?

The Golden Glove, produced in 2019, does not contain a post-credit scene. The film concludes its narrative without any additional scenes or content after the credits roll. The focus remains on the grim and unsettling story of the main character, Fritz Honka, and his disturbing actions throughout the film, leaving no room for a lighter or additional narrative twist in a post-credit format. The film's tone and themes are consistent throughout, emphasizing the dark and harrowing nature of its subject matter.

What motivates Fritz Honka to commit his crimes in The Golden Glove?

Fritz Honka, portrayed as a deeply troubled and isolated man, is driven by a combination of his desperate need for companionship and his violent impulses. His loneliness and inability to connect with others lead him to seek out vulnerable women in the seedy bar, The Golden Glove, where he preys on those who are often marginalized and desperate themselves. His motivations are rooted in a twisted desire for control and a misguided sense of intimacy.

How does the setting of Hamburg in the 1970s influence the story?

The setting of Hamburg in the 1970s plays a crucial role in establishing the grim atmosphere of The Golden Glove. The film captures the gritty, decaying urban landscape, filled with dimly lit bars and a sense of despair that permeates the lives of its characters. This backdrop not only reflects the societal issues of the time, such as poverty and addiction, but also serves as a breeding ground for Fritz's violent tendencies, highlighting the darkness that lurks beneath the surface of everyday life.

What is the significance of the character of The Golden Glove bar itself?

The Golden Glove bar serves as a central hub for the film, representing a microcosm of the darker aspects of society. It is a place where lost souls gather, and its patrons are often depicted as downtrodden and desperate. The bar's atmosphere, filled with smoke, dim lighting, and a sense of decay, mirrors the internal struggles of its characters, particularly Fritz. It becomes a stage for his predatory behavior, as he exploits the vulnerabilities of the women who frequent the bar.

How does Fritz's relationship with the women he targets evolve throughout the film?

Fritz's relationships with the women he targets are marked by a disturbing blend of manipulation and violence. Initially, he presents himself as a sympathetic figure, using charm to lure them in. However, as the film progresses, his true nature is revealed, and these interactions devolve into horrific acts of violence. The evolution of these relationships highlights Fritz's complete lack of empathy and his descent into madness, as he increasingly objectifies and dehumanizes his victims.

What role does the police investigation play in the narrative of The Golden Glove?

The police investigation serves as a contrasting element to Fritz's chaotic life, providing a sense of tension and impending doom. As the bodies of his victims begin to surface, the investigation unfolds in the background, showcasing the ineffectiveness of law enforcement in dealing with the grim realities of the underbelly of society. This subplot heightens the stakes for Fritz, as he becomes increasingly paranoid and reckless, ultimately leading to his downfall.

Is this family friendly?

The Golden Glove, produced in 2019, is not family-friendly and contains numerous potentially objectionable or upsetting scenes. Here are some aspects that may be distressing for children or sensitive viewers:

-

Graphic Violence: The film features intense and brutal scenes of violence, including murder and physical assault, which are depicted in a raw and unflinching manner.

-

Sexual Content: There are explicit sexual scenes that are graphic and disturbing, portraying non-consensual acts and exploitation.

-

Substance Abuse: The characters engage in heavy drinking and drug use, which is portrayed in a bleak and troubling context.

-

Mental Illness: The protagonist exhibits signs of severe mental instability, which may be unsettling for viewers, particularly in how it affects his behavior and interactions.

-

Dark Themes: The overall atmosphere of the film is grim, exploring themes of despair, loneliness, and moral decay, which can be emotionally heavy and distressing.

-

Disturbing Imagery: The film includes unsettling imagery that may provoke strong reactions, including depictions of death and decay.

Due to these elements, The Golden Glove is recommended for mature audiences only.