Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

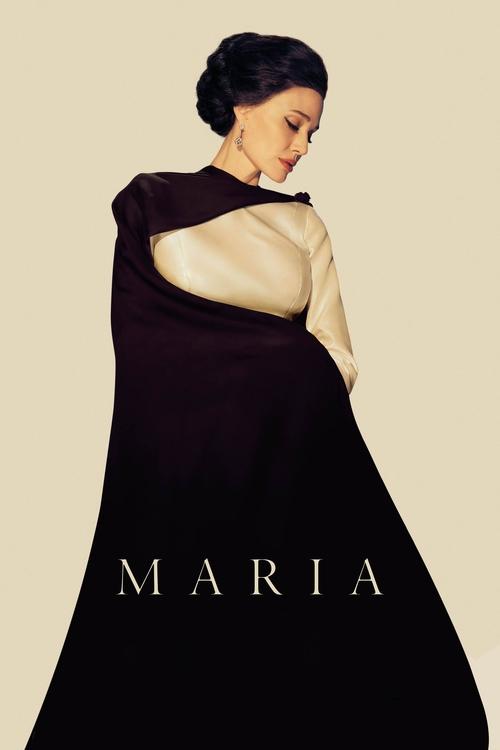

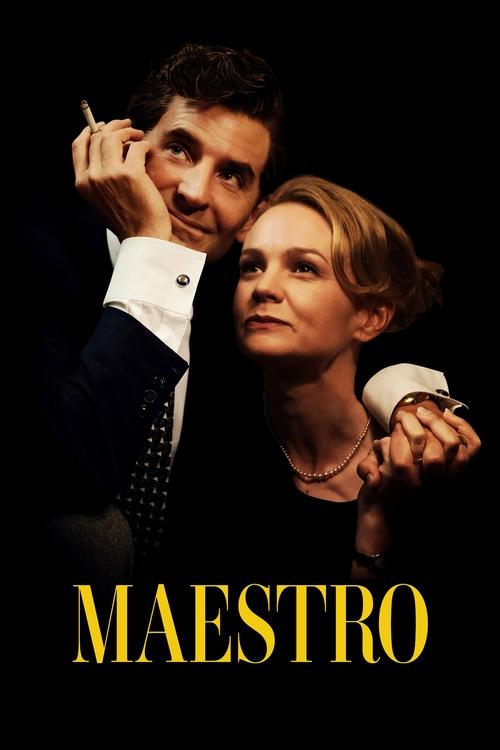

The film opens in 1977 in a modestly furnished Paris apartment where Maria Callas lives with two long-serving household attendants: Ferruccio, her attentive butler, and Bruna, her housekeeper. Maria is trying to regain the vocal power that made her an international star, working through an extended career hiatus brought on by years of declining health. Ferruccio repeatedly urges her to consult a physician and to adhere strictly to prescribed medication, but Maria refuses to give up an illicit habit: she is consuming Mandrax pills in quantities beyond what she claims are safe. She insists the pills help her cope and assist her voice, even as she experiences visual and auditory disturbances.

One morning Ferruccio and Bruna tell Maria that a television crew will come to interview her about her life. A young, eager filmmaker who calls himself Mandrax arrives, accompanied by a cameraman, and begins to film and question Maria. Ferruccio and Bruna do not acknowledge the crew; they are visible only to Maria. As the week progresses it becomes clear that the director and his assistant are hallucinations triggered by her overuse of Mandrax. Maria speaks with them, answers their questions, and allows the camera to roll, while her servants watch her engage with figures they cannot see.

During that same week Maria keeps a series of private appointments intended to assess whether she can return to the stage. She meets with the conductor Jeffrey Tate, inviting him to evaluate whether her instrument still possesses the range and clarity of earlier years. Tate listens in a small rehearsal, and their exchanges are focused, exacting: he asks her to sing passages, he takes notes, and he instructs her on breathing and placement. Maria brings an audio recorder to the session in order to capture her voice for her own record. As she sings, her voice appears frailer than in its prime; she cannot reach the crystalline high notes or the same dramatic coloratura that won her fame. After the session Tate is quiet and professional; the recording confirms what both of them apprehend--that Maria's vocal power no longer matches the heights of her greatest performances.

Prompted in part by the imagined interviews with Mandrax and by the rehearsals with Tate, Maria's memories begin to surface. She recalls the contour of a long, complex romantic relationship with the Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis. The film records the arc of that liaison with precise incidents: Onassis first courts her in 1957, Maria at first demurs, and then she falls deeply in love. She leaves her husband, Giovanni Battista Meneghini, breaking the marriage in order to be with Onassis. Over time the logistical demands of Onassis's life, his public visibility, and the relentless scrutiny of the press place restraints on Maria. She recognizes that the relationship curtails the artistic and personal freedom she cherishes; as a result she breaks with Onassis, withdrawing from their public life together. Despite the rupture she continues to see him in secret near the end of his life: the film shows Maria visiting Onassis while he is on his deathbed, and during that visit she confesses to him, plainly, that she loves him.

Other memories unearthed by her drug-fueled hallucinations have earlier origins. Maria remembers her teenage years during the Second World War, when her mother forces her to sing for Italian and German officers to obtain money. Those recollections are specific and visceral: Maria is a young girl on a stage or in a private drawing room, singing artfully for uniformed men as her mother watches, instruments of currency exchanged for her voice. Memory sequences of this period recur across the film, and they include the presence of her family, the pressure from her mother, and the indignity of having to perform in exchange for survival.

A marked scene occurs when Maria invites her older sister, Yakinthi, to the apartment. Yakinthi arrives and the two women confront a long history of familial grievance. They speak and remember their mother's treatment of them in wartime and after, and they reconcile to an extent, addressing grievances and broken trust that have lingered for decades. Their conversation is frank and close; the sisters touch on childhood scarcity, maternal manipulation, and the choices each made as a young woman. After the meeting Maria appears steadier emotionally, but still physically fragile and dependent on pills she insists she needs.

Ferruccio finally persuades Maria to see a professional physician, Dr. Fontainebleau. In the first consultation Maria downplays her dependency and lies about the frequency and quantity of Mandrax intake. She professes commitment to medical supervision while minimizing the medications she has been using, and she resists the full battery of diagnostic procedures. Dr. Fontainebleau is courteous at first, but on their second appointment he confronts Maria with clinical reports supplied to him by Ferruccio; those papers document deterioration in her health. The doctor explains plainly that her medical condition has worsened and that the tests indicate a significant decline in the capacities required for operatic singing. He tells her that, according to the reports, she may no longer be able to sing professionally. Maria attempts to maintain her composure; she does not concede the point emotionally, but the medical evidence disappoints and unnerves her.

Following the second medical consultation Maria schedules one final session with Jeffrey Tate. She brings the audio recorder to document her voice in what she frames as an effort to preserve it. In a closed rehearsal room she performs an aria, aiming for the familiar phrasing and emotional intensity that once marked her interpretations. Tate follows the score and is intent on technical detail; he encourages phrasing and warns her not to strain. The recording captures a voice that is expressive and still characterized by unusual interpretive sensibility, yet it is diminished in volume and flexibility. Afterward a journalist from the newspaper Le Figaro who had been spying outside the rehearsal intrudes, stepping into the doorway and speaking aggressively about Maria's career and decisions. He questions her abruptly, asking about the choices that led to her absence from the stage and about her relationship with Onassis. Ferruccio interposes and pushes the journalist forcefully out of the room, closing the door on the intrusion. The confrontation leaves Maria shaken; she thanks Ferruccio and Bruna for their steadfast presence and for managing the practical indignities she has been forced to endure.

That night Maria returns to her apartment routines. She unpacks memories, reviews the recorded rehearsals, and speaks sometimes to the imaginary director Mandrax, who probes and cajoles her to confront more of her past. The hallucinated cameraman and filmmaker reappear in her living room; Maria responds to their questions as if she is participating in a filmed autobiography. Ferruccio and Bruna do not react to the filmmakers because they cannot perceive them; they treat Maria with habitual kindness, adjusting her pillows, preparing a light meal, and encouraging her to take the legitimately prescribed medicines she has been avoiding.

The following morning Ferruccio and Bruna leave to run errands and buy groceries. Left alone, Maria makes a deliberate decision. She opens the shutters of her apartment to the Parisian street below, positions herself near the piano, and prepares to sing. She chooses to perform "Vissi d'arte," the aria from Puccini's Tosca that has long been associated with her artistry. Maria sings with concentration and emotional force; she shapes each phrase with the intelligence and dramatic attention that defined her performances, though the mechanics of her voice betray age and infirmity. She leaves the windows open so her sound spills into the street. Passersby below, attracted by an unusual, powerful soprano voice projecting from an upstairs apartment, stop to listen. A growing crowd gathers on the pavement, faces turned toward the building as the aria unfolds. People on the sidewalk, in cafes, and in passing cars all pause to attend to the music rising from the window.

Inside the apartment Ferruccio and Bruna, returning from their shopping, are among those who hear the singing as they approach the building. They ascend the stairs and stand briefly outside Maria's door, listening without interrupting. The film also stages a sequence in which Aristotle Onassis and the filmmaker Mandrax appear in the apartment, silent and firm in their attention to Maria's performance. Those figures are ephemeral and unreal in the eyes of the household staff: Onassis' presence reads as an apparition of memory, Mandrax's as an hallucination induced by medication. Both vanish from sight as Maria completes the aria, swallowed again by the ordinary light of the apartment and the city outside.

When the aria ends Maria is motionless. Ferruccio and Bruna enter the living room and find her lying on the floor. She is already dead. There is no sign of a struggle or of external harm; her body lies quietly beside the chair where she had been rehearsing. Ferruccio checks for a pulse, finds none, and reaches for the telephone. He dials Dr. Fontainebleau to report that Maria has collapsed and is unresponsive. The doctor receives the call and instructs Ferruccio to call the police and an ambulance; he promises to come to the apartment. Within minutes uniformed officers and emergency medical personnel arrive at the building. They ascend to the apartment, observe the scene, and examine Maria's body. The attending personnel and Dr. Fontainebleau confer with Ferruccio and Bruna. The film offers the discovery in procedural detail: the ambulance attendants pronounce death at the scene, the police take statements from Ferruccio and Bruna, and officials note the absence of signs of foul play.

The narrative does not show anyone attacking or killing Maria; no character is depicted as having murdered her. Instead, the film presents her death as a sudden collapse that follows her last, open performance. Authorities treat the death as a medical event rather than a criminal act; emergency responders and the doctor describe the condition as consistent with severe underlying health problems and the possible effects of medications, though the film does not provide a definitive, onscreen cause of death. Ferruccio remains at her side, distraught, and Bruna tends to practical matters, calling relatives and gathering Maria's personal effects. Reporters and neighbors congregate outside the building as officials complete the required notifications.

Following the official procedures, the film closes on still images and a quiet apartment now bereft of the woman who once filled it with song. Ferruccio closes the shutters, Bruna collects small belongings, and the apartment's rooms fall into silence. Maria Callas has died in the place where she tried to reclaim her voice; no onscreen character is responsible for killing her. The final shot remains on the emptied apartment and on the medical personnel leaving the premises after documenting the death, while neighbors and the two remaining companions stand on the street below, holding the memory of the aria that drifted into Paris that morning.

What is the ending?

Short, Simple Narrative of the Ending

In the final days of her life, Maria Callas, living in Paris with her butler Ferruccio and housemaid Bruna, struggles with failing health and a lost singing voice. After a final, private singing session where she confronts the decline of her talent, she returns home. One morning, while Ferruccio and Bruna are out, Maria sings "Vissi d'arte" one last time with her windows open, drawing a crowd of Parisians. Her performance is a moment of peace and acceptance. When Ferruccio and Bruna return, they find Maria has died. Ferruccio calls the doctor to report her death, and authorities arrive as the film concludes.

Expanded, Chronological, Scene-by-Scene Narration of the Ending

The film's final act unfolds in Maria's Paris apartment, where she has become increasingly isolated, dependent on medication, and haunted by memories and hallucinations. Her butler, Ferruccio, maintains a careful log of her pill intake, aware that she often takes more than she admits. Maria's health visibly deteriorates; she refuses to eat, wanders the apartment at odd hours, and resists seeing a doctor despite Ferruccio's insistence.

One day, Maria finally agrees to see Dr. Fontainebleau. In their first meeting, she lies about her drug use, but in a subsequent appointment, the doctor confronts her with medical reports provided by Ferruccio, revealing that her condition has worsened and she may never sing again. This news devastates Maria, who has defined herself by her voice and career.

Determined to prove she can still sing, Maria arranges a private session with her old friend and collaborator, Tate. She brings an audio recorder, hoping to capture her voice as it once was. During the session, it becomes painfully clear that her voice no longer matches the heights of her prime. Maria is visibly sorrowful and frustrated, while Tate encourages her to keep trying. Their session is interrupted by a journalist from Le Figaro, who has been spying on Maria. He confronts her with intrusive questions about her career and decline, but Ferruccio intervenes and escorts him out.

Back at her apartment, Maria expresses deep gratitude to Ferruccio and Bruna for their years of loyalty and care. She acknowledges their efforts to look after her, even as she has resisted their help. The next morning, while Ferruccio and Bruna are out buying groceries, Maria, alone in the apartment, decides to sing "Vissi d'arte" from Tosca one final time. She opens her windows wide, and her voice carries out into the Parisian street. Passersby stop to listen, drawn by the beauty and sorrow in her performance. Ferruccio and Bruna, returning home, hear her singing from the street and stand silently, moved by the moment. Inside the apartment, Maria's hallucinations briefly manifest--figures from her past, including Aristotle Onassis and the specter of her medication (Mandrax), appear to listen before vanishing.

When Ferruccio and Bruna enter the apartment, they find Maria lying lifeless on the floor. Ferruccio immediately calls Dr. Fontainebleau to report her death. Authorities arrive to take charge of the scene. The film ends with Maria's death, her final act of singing symbolizing both her acceptance of the end and a fleeting return to the artistry that defined her life.

Fate of the Main Characters at the End

- Maria Callas: Dies alone in her apartment after singing one last aria, having made peace with the loss of her voice and the end of her career. Her death is discovered by Ferruccio and Bruna upon their return.

- Ferruccio: Remains loyal to Maria until the end, caring for her daily needs and monitoring her health. He is the one who finds her body and contacts the doctor, fulfilling his role as her protector and confidant.

- Bruna: Shares in the care of Maria, providing emotional support and companionship. She witnesses Maria's final performance from the street and is present when Maria's death is discovered.

- Dr. Fontainebleau: Informed of Maria's death by Ferruccio and presumably oversees the official procedures following her passing.

- Tate: Participates in Maria's final attempt to sing, offering encouragement but unable to restore her lost voice. He does not appear in the very final scenes.

- Yakinthi (Maria's sister): Reconciles with Maria earlier in the film, urging her to let go of the past. She is not present at the moment of Maria's death.

- Aristotle Onassis and Mandrax: Appear only as hallucinations during Maria's final performance, symbolizing her unresolved past and addiction, before disappearing as she finds peace.

Key Points the Movie Highlights in the Ending

The ending emphasizes Maria's struggle to accept the loss of her artistic identity and the inevitability of her mortality. Her final act of singing, performed not for an audience but for herself, represents both a surrender and a triumph--a fleeting reconnection with the artistry that once defined her. The loyalty of Ferruccio and Bruna underscores the theme of care and companionship in the face of decline, while Maria's hallucinations reflect her unresolved relationships and regrets. The film portrays her death not as a tragedy, but as a moment of grace and closure, surrounded by the echoes of her greatest performances and the quiet devotion of those who loved her.

Is there a post-credit scene?

Yes, the movie Maria (2024) does have a post-credits scene. It shows real footage of the actual Maria Callas, the legendary opera singer portrayed in the film. This brief appearance of the real Callas serves as a poignant contrast to the dramatized portrayal and adds a layer of authenticity to the biopic.

The main film ends with Maria singing "Vissi d'arte" one last time in her Paris apartment, surrounded by people outside listening, before she is found dead by her butler Ferruccio and housekeeper Bruna. After the credits, the real Maria Callas appears, providing a final, real-life connection to the story told in the film.

What role does the hallucinated filmmaker named Mandrax play in Maria's story?

Mandrax is a hallucination caused by Maria's overuse of medication, personified as a young filmmaker who interviews her about her life. He is not seen by others and prompts Maria to recall memories and confront her past, serving as a narrative device to explore her inner thoughts and struggles during her final days in Paris.

How is Maria Callas's relationship with Aristotle Onassis depicted in the film?

The film shows Maria's complex relationship with Aristotle Onassis, including their initial romance after she left her husband, the public scrutiny that led her to leave Onassis, and her secret visits to him on his deathbed where she admits she loved him. It also highlights Onassis's later marriage to Jacqueline Kennedy and the impact of this on Maria's life and career.

What is the significance of Maria's interactions with her housekeeper Bruna and butler Ferruccio?

Bruna and Ferruccio are Maria's devoted companions in her Paris apartment, providing warmth and humor. Ferruccio insists she see a doctor and take proper medication, highlighting her declining health and addiction struggles, while Bruna offers emotional support, reflecting Maria's isolation and dependence on her close staff during her final days.

How does the film portray Maria Callas's struggle with her singing career in her final days?

Maria is shown attempting to sing again after a long hiatus due to health issues. She attends private sessions with conductor Jeffrey Tate to assess if she can perform, but her voice is failing. The film also depicts her addiction to Mandrax, which she claims helps her despite side effects, and her emotional conflict over her lost ability to sing and perform.

What past traumas and family dynamics are revealed about Maria Callas in the film?

The film includes black-and-white flashbacks showing Maria and her sister being forced by their mother to sing for soldiers and men for money, implying a traumatic childhood. Maria also expresses lingering trauma related to her mother, including a scene where she avoids a Mexican restaurant because of a painful memory involving her mother, revealing deep emotional scars influencing her present state.

Is this family friendly?

Maria (2024) is not considered family friendly and is best suited for mature audiences. The film is rated R primarily for language, including sexual references, and contains several elements that may be upsetting or inappropriate for children or sensitive viewers. Here is a detailed, non-spoiler summary of potentially objectionable or distressing content, organized by scene type and emotional impact:

Language and Sexual Content

- Strong Language: The film contains at least 10 uses of the F-word, along with other strong language and occasional blasphemy. These expletives are often delivered in moments of high emotion, reflecting Maria's frustration, despair, or confrontations with others.

- Sexual References: There are brief, non-graphic references to sex trafficking during wartime, as well as discussions of adultery and extramarital affairs. These are presented through dialogue rather than visual depictions, but the implications are clear and may be disturbing, especially the notion of young women being sold by their mother.

- Sexual Situations: A man is shown attempting to seduce a married woman, and there are implications of sexual relationships outside of marriage, though nothing is shown on screen. In one scene, a woman begins to undress but is interrupted by a German soldier--this moment is tense but not explicit.

Substance Use

- Alcohol and Smoking: Adult characters are frequently seen drinking and smoking in social settings, contributing to a mature atmosphere. Maria herself smokes cigarettes throughout the film, often in moments of reflection or distress.

- Prescription Drug Abuse: Maria is depicted abusing her sedative prescription (Mandrax), taking pills in multiple scenes. Her reliance on medication is portrayed as a coping mechanism for emotional pain and isolation, with visible physical and emotional consequences.

Violence and Disturbing Imagery

- Mild Violence: A dead body is briefly shown, though the scene is not graphic. The moment is somber and may be unsettling for sensitive viewers.

- Emotional Distress: Maria experiences significant emotional turmoil, including scenes where she collapses, imagines people who aren't present, and burns theatrical costumes in a fit of anguish. These sequences are intense and convey her mental state through visual metaphor rather than explicit violence.

- Illness and Decline: There are discussions of illness and physical decline, with Maria's servants noting her refusal to eat for days at a time. The portrayal of her deteriorating health is poignant and may be distressing.

Psychological Themes

- Isolation and Loneliness: Much of the film takes place in Maria's Paris apartment, where she is attended only by two loyal servants. The atmosphere is claustrophobic, and Maria's sense of isolation is palpable, which may be emotionally heavy for some viewers.

- Family Estrangement: References are made to Maria's fractured relationship with her mother, adding a layer of familial pain to her story.

Overall Tone

The film's pacing is slow and contemplative, focusing on Maria's internal struggles rather than action or spectacle. The emotional weight, mature themes, and occasional strong language make it unsuitable for children or those sensitive to depictions of substance abuse, emotional distress, and implied sexual situations.

In summary, Maria (2024) is a psychologically intense, adult-oriented biopic that deals frankly with themes of addiction, loneliness, and personal legacy. While it avoids graphic violence or nudity, its mature content and emotional depth are likely to be challenging for younger or more sensitive audiences.