Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

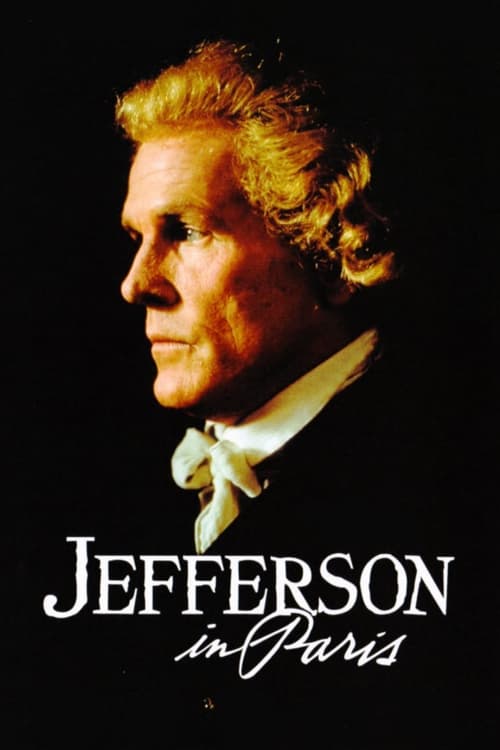

Jefferson in Paris (1995): Complete Plot Narrative

The story unfolds in two temporal frames. An elderly narrator, decades removed from the events, begins recounting the tale of Thomas Jefferson's years in Paris--a period that would define both his public ascent and his private moral failures.

Part One: Arrival and Enchantment

In 1784, Thomas Jefferson, the widowed author of the Declaration of Independence, arrives in Paris as the newly appointed United States Minister to France, replacing Benjamin Franklin at the court of King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette. He is a man of intellectual appetite and architectural curiosity, eager to absorb the refinements of French civilization. Yet he carries with him a profound grief and a solemn vow made to his deceased wife: he will never remarry.

Jefferson settles into his Paris residence with his eldest daughter, Patsy Jefferson, a young woman of strong moral conviction who has inherited her father's intensity and her mother's protective devotion. Patsy is acutely aware of her father's promise and fiercely guards his reputation and his fidelity to her mother's memory. She becomes his emotional anchor in this foreign court, possessive of his attention and wary of any woman who might threaten the sanctity of their family bond.

At the salons and aristocratic gatherings of Paris, Jefferson encounters a world of intellectual ferment and political possibility. French liberals and enlightened aristocrats gather around him, hopeful that the American Revolution represents a new dawn for human liberty. Yet in these same drawing rooms, they confront him with an uncomfortable question: How can a man who authored words about the inalienable rights of all men continue to hold other human beings in bondage? Jefferson acknowledges that slavery is evil and that he once attempted to insert an anti-slavery clause into the Declaration of Independence, but when pressed on why the American Revolution left this institution intact, he offers no satisfying answer. The contradiction hangs in the air between them--a man of principle who profits from the denial of those very principles.

It is in these refined circles that Jefferson meets Maria Cosway, a beautiful Anglo-Italian painter and musician whose artistic sensibility mirrors his own intellectual curiosity. Maria is married to Richard Cosway, an English painter of considerable vanity and little substance--a "world-class fop" whose frivolous nature throws Jefferson's seriousness into sharp relief. Yet Maria herself possesses depth. She and Jefferson begin as friends, their connection deepening through conversations about art, philosophy, and the human heart. Their friendship quickly becomes something more--a romantic attachment that neither fully acknowledges but both intensely feel.

Maria becomes Jefferson's confidant and correspondent, and their relationship exists in a state of beautiful, anguished tension. Jefferson is drawn to her with genuine affection, yet he is bound by his vow to his dead wife. He cannot offer Maria marriage or a conventional future. The relationship becomes a dialogue between Head and Heart--reason and emotion--with Jefferson perpetually caught between his promise to the past and his longing in the present.

Part Two: The Arrival of Sally

The equilibrium of Jefferson's Paris life is disrupted by news from Virginia: one of his daughters remaining in America has died. Grief-stricken, Jefferson sends for his youngest daughter, Polly, to join him in Paris. With her comes a young enslaved girl, her maid and companion--Sally Hemings.

Sally is approximately fifteen years old when she arrives in France. What makes her presence particularly significant--and morally complex--is a fact that the film makes explicit: Sally Hemings is the half-sister of Jefferson's late wife. They share the same white father, John Wayles, though different mothers. This means Sally is not merely Jefferson's property; she is also the aunt of his daughters, a blood relation whose existence testifies to the sexual exploitation that undergirds slavery itself.

Sally's brother, James Hemings, is already in Paris, having been brought there years earlier to train as a French chef for Jefferson's household at Monticello. James has experienced a taste of relative freedom in France, learning a skilled trade and moving through Parisian society with a degree of autonomy impossible in Virginia. He has become a man of professional accomplishment and growing consciousness of his own worth.

Jefferson begins to take notice of Sally in ways that go beyond the master-servant relationship. He gives her small gifts--a necklace among them--tokens that signal a shift from simple service to something more intimate. Sally begins visiting Jefferson in his bedroom, encounters that start as what the film describes as "flighty flirtations" but progress into a sexual relationship. The power imbalance is absolute: she is enslaved, he is her owner; she is fifteen, he is in his forties; she is his property, and she cannot refuse him.

Patsy observes the growing intimacy between her father and Sally, and she is horrified. She calls the situation "unspeakable"--a word that captures both her moral revulsion and her sense that this transgression violates everything her family represents. She watches her father betray his promise to her mother by taking an enslaved girl to his bed, and she cannot forgive it. Yet rather than confront him directly, Patsy takes a different course. She implies the truth to Maria Cosway, insinuating what is happening between Jefferson and Sally, weaponizing this knowledge out of jealousy and moral outrage.

Maria, already feeling the constraints of Jefferson's emotional unavailability and his vow to his dead wife, now learns that he is also sexually involved with a fifteen-year-old enslaved girl--a girl who is the sister of his late wife, the aunt of his daughters. The revelation is devastating. Maria witnesses the familiarity between Jefferson and Sally firsthand, observing signs of intimacy that confirm Patsy's insinuations. The man she has come to love is revealed as morally indifferent to the exploitation of a child under his absolute power. Maria's feelings shift from romantic longing to disillusionment and disgust. She swiftly ends her relationship with Jefferson, withdrawing her affection and her presence from his life.

Part Three: Confrontations and Moral Reckoning

The household becomes a site of moral crisis. James Hemings, observing the situation and reflecting on his own years of relative freedom in Paris, begins to articulate what the film's other characters largely avoid saying directly. He confronts Jefferson about the fundamental hypocrisy of his position. How can a man who speaks eloquently of liberty continue to hold human beings in bondage? How can he claim to be enlightened while enslaving his own relatives? James has tasted freedom; he has developed a valuable skill; he has moved through the world as something approaching a free man. The prospect of returning to Virginia, of resuming his status as enslaved property, becomes intolerable to him.

These confrontations between James and Jefferson are described as the best-written scenes in the film, moments where the character of James is willing to directly address questions that the narrative otherwise allows to "slip quietly past." He speaks truths that Jefferson's French liberal friends hint at but never fully articulate, and that Jefferson himself refuses to honestly confront.

The film also documents Jefferson's offer to James and Sally: a choice between freedom and return to Monticello. Yet this offer is shadowed by Jefferson's paternalistic assumption that they will choose to stay with him, that they will recognize him as "the best master in Virginia" and prefer his ownership to the uncertainty of freedom. The choice, in other words, is not truly free--it is constrained by the power Jefferson holds over them, by their lack of resources, and by the social world's refusal to grant them genuine autonomy.

Part Four: The Final Reckoning

As Jefferson's diplomatic mission draws to a close and the French political situation grows increasingly unstable, George Washington offers Jefferson the post of Secretary of State in the new American government. Jefferson accepts the position, which represents the pinnacle of his political ambitions. He begins preparing to sail back to America with his family.

It is at this moment, as departure becomes imminent, that Sally reveals to James that she is pregnant by Jefferson. The revelation carries enormous weight. In France, any child born to Sally would be born free. In Virginia, the child will be enslaved, following the legal status of its mother. The pregnancy crystallizes the stakes of the choice before them.

James urgently pleads with Sally to remain in France, to stay where she and her child could be free. He cannot bear the thought of his sister returning to slavery, of her child being born into bondage. He articulates the possibility of freedom, of a life beyond Jefferson's control. But Sally, emotionally bound to Jefferson and lacking other support networks or resources, resists his pleas. She cries out in anguish: "Where's I going?"--a line that encapsulates the psychological captivity that supplements her legal enslavement. She has no family outside Jefferson's household, no independent means, no clear path to survival in a foreign country. The man who enslaves her is also the only world she knows.

Despite James's desperate appeals, Sally chooses to return to Virginia with Jefferson. She will board the ship bound for America, pregnant with Jefferson's child, accepting that her child will be born into slavery. Her decision is not a free choice; it is the only choice available to someone with no genuine alternatives.

James Hemings does not want to return. The film emphasizes his refusal, his anger at being expected to resume enslavement after tasting freedom. Whether he ultimately returns or remains in France is left ambiguous in the narrative emphasis, but the emotional climax is his confrontation with the reality that his sister will go back into bondage despite his efforts to save her.

Epilogue: The Departure

Jefferson leaves Paris politically elevated--soon to become Secretary of State, a position of tremendous power and influence in the new American republic. Yet he departs morally compromised. His romance with Maria Cosway is finished; she has withdrawn from his life after realizing the truth about Sally. The intellectual and emotional connection that sustained him through his Paris years has been severed by his own actions.

He sails home carrying with him the unresolved contradictions of his life: a man who wrote that all men are created equal, who argued eloquently for human liberty, who condemned slavery as evil--yet who enslaved human beings, who fathered children with an enslaved girl, who offered the illusion of choice while maintaining absolute power over those he claimed to care for. The French Revolution, which will soon transform Europe, looms on the horizon, but Jefferson will not witness it. He returns to America with his daughters and with Sally, pregnant and bound to him by both law and circumstance.

The narrative frame returns briefly to the elderly narrator in the American Midwest, reflecting on the story just told--a story of a man of principle undone by his own failures, a story of ideals betrayed by the gap between public philosophy and private action, a story of a young enslaved girl whose humanity was denied by the man who claimed to believe in human rights.

The film ends not with resolution but with the weight of these contradictions hanging in the air, a portrait of a founding father whose legacy would be forever shadowed by the enslaved people he owned and the promises he broke--to his wife, to his ideals, and to those who had no power to hold him accountable.

What is the ending?

In the ending of "Jefferson in Paris," Thomas Jefferson prepares to leave France after his diplomatic mission. He reflects on his time in Paris, his relationships, and the complexities of his life. The film concludes with Jefferson's departure, leaving behind a legacy intertwined with both personal and political struggles.

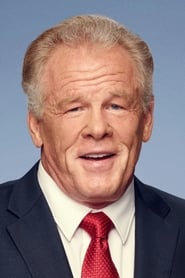

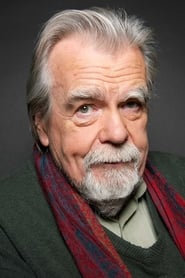

As the final scenes unfold, we see Jefferson, played by Nick Nolte, standing in his Parisian residence, surrounded by the remnants of his life in France. The atmosphere is heavy with nostalgia and a sense of loss. He is preparing to return to America, a place that feels increasingly distant from the vibrant life he has led in Paris. The camera captures the elegant yet somber surroundings, emphasizing the contrast between Jefferson's past experiences and his uncertain future.

In a poignant moment, Jefferson reflects on his relationship with Sally Hemings, portrayed by Thandiwe Newton. Their bond, filled with both affection and tension, is a central theme throughout the film. As he prepares to leave, he acknowledges the complexities of their relationship, marked by love, societal constraints, and the realities of slavery. The emotional weight of this connection lingers in the air, highlighting Jefferson's internal conflict and the moral dilemmas he faces.

Jefferson's departure is not just a physical journey but also a symbolic one. He leaves behind the ideals of the Enlightenment that he embraced in France, grappling with the contradictions of his own life as a slave owner. The film captures his sense of duty to his country, yet it also portrays a man torn between his principles and the societal norms of his time.

As he boards the ship to return to America, Jefferson looks back at the city that has shaped him. The final shot lingers on his face, revealing a mixture of determination and sorrow. He is a man who has experienced the heights of intellectual and cultural enlightenment, yet he is also burdened by the weight of his own choices.

The film concludes with a sense of unresolved tension, leaving the audience to ponder the legacy of Thomas Jefferson. His fate is intertwined with the ideals of freedom and the harsh realities of his life, encapsulating the complexities of a man who played a pivotal role in shaping a nation while grappling with his own moral contradictions. The final moments serve as a reminder of the enduring impact of Jefferson's life and the unresolved issues of race and liberty that continue to resonate.

Is there a post-credit scene?

The movie "Jefferson in Paris," produced in 1995, does not have a post-credit scene. The film concludes with a focus on Thomas Jefferson's experiences and relationships during his time as the American ambassador to France, particularly highlighting his interactions with the French culture, his political ambitions, and his complex personal life. The narrative wraps up without any additional scenes or content after the credits.

What is Thomas Jefferson's relationship with Sally Hemings in the film?

In 'Jefferson in Paris', Thomas Jefferson's relationship with Sally Hemings is portrayed as a complex and intimate bond. Jefferson, played by Nick Nolte, is depicted as being deeply affected by Hemings, who is portrayed as a young enslaved woman. Their relationship evolves from a master-servant dynamic to a romantic involvement, highlighting the emotional and moral conflicts Jefferson faces as he grapples with his feelings for her while also being a prominent figure advocating for liberty and equality.

How does Jefferson's time in France influence his views on slavery?

During his time in France, Jefferson is exposed to Enlightenment ideals and the burgeoning concepts of liberty and equality. This exposure leads him to reflect on the institution of slavery, which he struggles with internally. The film illustrates his growing discomfort with slavery, particularly as he witnesses the freedom enjoyed by the French people, contrasting sharply with the reality of his own enslaved workers, including Sally Hemings.

What role does the character of John Adams play in the film?

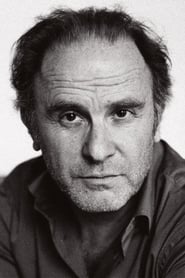

John Adams, portrayed by David Morse, serves as a foil to Jefferson in 'Jefferson in Paris'. Their interactions reveal differing philosophies on governance and personal ethics. Adams is depicted as a staunch critic of slavery and a more pragmatic politician, often challenging Jefferson's ideals. Their conversations reflect the tension between their friendship and their contrasting views on liberty, governance, and morality.

How does the film depict Jefferson's relationship with his daughters?

Jefferson's relationship with his daughters, particularly Martha and Maria, is portrayed with a mix of affection and paternal concern. The film shows him as a loving father who is deeply invested in their education and future. However, his political duties and personal conflicts often create a distance between him and his daughters, highlighting the sacrifices he makes for his public life and the emotional toll it takes on his family.

What is the significance of the character of Madame de Staël in the story?

Madame de Staël, played by Greta Scacchi, is a significant character in 'Jefferson in Paris' as she represents the intellectual and cultural milieu of France. Her interactions with Jefferson provide insight into the political and philosophical debates of the time. She is portrayed as a strong-willed and intelligent woman who challenges Jefferson's views, particularly regarding women's roles in society and the nature of freedom, thus enriching the narrative with themes of gender and power.

Is this family friendly?

"Jefferson in Paris," produced in 1995, is a historical drama that explores the life of Thomas Jefferson during his time as the American ambassador to France. While the film is rich in historical context and character development, it does contain several elements that may be considered objectionable or upsetting for children or sensitive viewers.

-

Themes of Slavery: The film addresses the complex and troubling aspects of slavery, particularly Jefferson's relationship with his enslaved servant, Sally Hemings. This includes discussions and depictions of the power dynamics and moral dilemmas surrounding slavery.

-

Sexual Content: There are scenes that imply a romantic and sexual relationship between Jefferson and Hemings, which may be uncomfortable for younger audiences. The film portrays intimate moments that suggest a deep emotional and physical connection.

-

Political Intrigue and Conflict: The film delves into the political tensions of the time, including discussions of revolution and the impact of war. These themes may be intense for younger viewers, as they involve betrayal, conflict, and the moral complexities of governance.

-

Emotional Turmoil: Jefferson's character experiences significant emotional struggles, including feelings of isolation, guilt, and conflict over his beliefs and actions. These themes may resonate deeply and could be distressing for sensitive viewers.

-

Historical Context of Violence: The film references the violence and upheaval of the French Revolution, which may include discussions of death and societal chaos, potentially unsettling for some audiences.

Overall, while "Jefferson in Paris" offers a rich narrative and historical insight, its mature themes and emotional depth may not be suitable for all children or sensitive viewers.