Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

In the darkness, before there is any place or time, a child's voice asks a question that hangs like dust in still air: "¿Qué es un fantasma? What is a ghost?" A calm, older man's voice answers, musing that a ghost might be a tragedy doomed to repeat itself, or a moment of pain suspended in time, like an insect trapped in amber, or simply someone who is dead but still remembers being alive. The idea lingers, a soft premonition, as if the story itself is already over and is being told again.

Then the darkness opens onto Spain in 1939, the final days of the Spanish Civil War. The Nationalist forces of General Francisco Franco are winning, the Republican front crumbling. The land around a small convoy is arid and ocher, like scorched bone. A bumpy dirt road runs through a desert-like plain. A ragged old car rattles along it, raising powdery dust into the heated air.

In the back seat sits Carlos, twelve years old, dark-haired, watchful. His father has died fighting for the Republican cause; his tutor, a thin, nervous man working for the losing side, now ferries the boy away from the front. In the car, Carlos clutches a suitcase with all he owns and a small book of stories, trying to understand that his life has been cut off in the middle of a sentence.

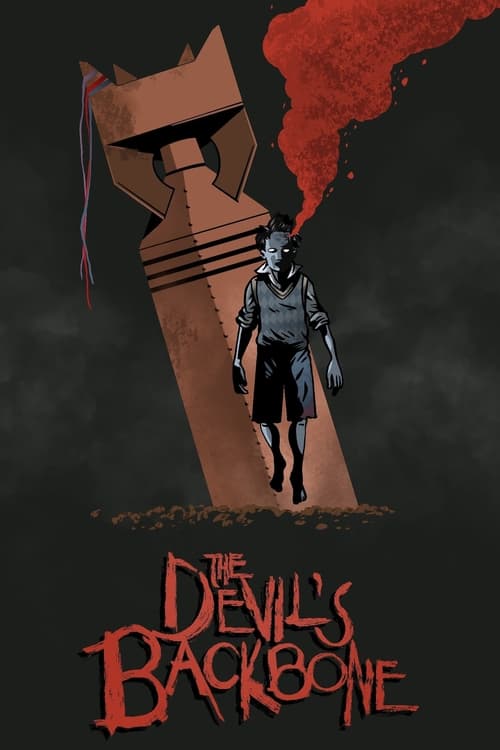

The car pulls up at an isolated orphanage, a low cluster of stone and plaster buildings in the middle of nowhere. The place looks part fortress, part crumbling mission. In the courtyard stands an enormous unexploded bomb, nose buried in the dirt, tail fins twisted. It looms taller than a boy, rusted and inert, but a faint, steady ticking can be heard if one stands close enough. It fell one night and never detonated, now a metal monument to violence that might yet happen.

On a wall at the edge of the courtyard, a gigantic crucifix has been mounted to present the orphanage as a Catholic boarding school, a pious façade to protect this refuge for the abandoned children of leftist Republicans. Franco's advancing troops and their supporters see crosses and rosaries and pass by, while inside, the last tatters of the Republican dream try to survive.

Carlos climbs out. The heat hits him. The tutor speaks hurriedly with the staff; the boy can't hear the words but feels the urgency, the finality. The man who brought him here is eager to return to the front and his doomed cause. Without a goodbye that feels like enough, he leaves Carlos standing alone in the wide courtyard, watched by other boys through open windows and cracked doors.

From the main building emerges Carmen, a woman in late middle age with stern, intelligent eyes and tightly pinned hair. Her right leg ends below the knee; she walks with a careful click of a wooden prosthetic leg, each step a labor she refuses to show as pain. Her late husband was a leftist leader; his ideals brought them here and left her with the task of sheltering the dispossessed.

Beside her comes Dr. Casares, an elderly man with a stooped back, dignified beard, and melancholy gaze. He is a doctor by training, a rationalist and Republican intellectual by conviction. He looks at the children as more than bodies to be kept alive; he sees their minds, their fears, the shadows that stalk them. There is a hint of self-absorption, of a man who lives partly in books, but he cares.

Carmen studies Carlos's papers, looking over his name, his father's dead status. She accepts him; he becomes another ward of this last redoubt. Somewhere, she notes the date--late 1939, close to the war's end--but dates are already starting to matter less than survival.

Watching from a distance is Jacinto, the orphanage's caretaker and handyman, around thirty, handsome in a hard, predatory way. He leans against a wall near the courtyard, smoking, eyes narrowed. His hair is slicked back; his shirt clings to a muscled torso. Once he was a boy at this very orphanage, another nameless child of the war. Now he carries keys, tools, and simmering resentment. The building is his hunting ground, and he moves through it with the practiced familiarity of someone who knows every hidden room.

With him, inside the kitchen and quarters, is Conchita, a young maid with dark hair and a quiet, tired beauty. She sleeps with Jacinto at night in secret, or as secret as anything can be in a confined place full of sharp-eyed children. She loves him in a way that grows increasingly desperate as she senses the cruelty beneath his skin.

The boys in the orphanage, maybe a dozen of them, gather around Carlos, testing him with curious stares and casual cruelty. At their center is Jaime, the oldest, tough and wiry, with a mop of hair and a tight jaw. Jaime is the bully because he has learned that children in war must become hard or be crushed. He carries a small knife and a sketchbook, hiding his talent for drawing behind bravado and violence.

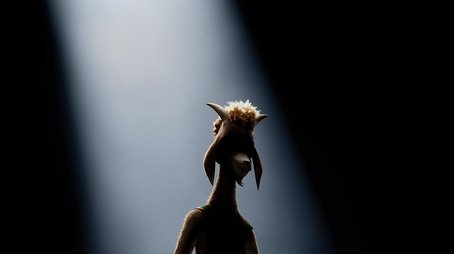

As they show Carlos his bed--a metal frame with thin bedding in a long dormitory--someone whispers the most important secret the place has: "There's a ghost here." The name passes from boy to boy like a chill draft: Santi. Some call him Santito. Once, Santi was one of them. Now he is something else.

Night falls quickly on the plateau, the wind humming around corners, rattling shutters. In the darkness, lying in his new bed, Carlos hears sounds: sighs that are not the breathing of boys, a faint wet dragging, a whisper too quiet to form words. He sees, on the far wall of the dormitory, a faint silhouette: a small, blurred figure with a pale, cracked face and a halo of drifting particles like dust suspended in water. His breath catches, but when he blinks, the shape is gone.

The next morning, the daily life of the orphanage unfolds in threadbare routine: rationed food, lessons in a classroom where Dr. Casares sometimes speaks of poetry or science as if the outside world were not collapsing. He keeps a jar in his office filled with malformed fetuses in amber liquid, medical oddities that he treats with a strange tenderness. He calls one jar "the devil's backbone", a fetal spine curved eerily, and explains his theory that superstition and science are two ways of facing the same fears. The phrase echoes the title that seems to hover over everything: The Devil's Backbone.

Carmen manages supplies and discipline. Beneath her composure, she is exhausted. The wooden leg rubs her skin raw; at night she takes it off to reveal red, abraded flesh, and rubs it with alcohol while clenching her jaw. She shares a quiet, complicated intimacy with Dr. Casares--a friendship, a half-buried love that has never fully become physical. Casares, impotent, loves her in a resigned, melancholic way, and she accepts his company, his sober kindness, but also needs more immediate warmth.

That warmth, for a reckless time, has come from Jacinto. When he thinks no one sees, he slips into Carmen's room, kisses her roughly, pushes up her skirt, and they have hurried sex in the dim light, the wooden leg leaned against the bed. Afterward, Jacinto probes with his eyes more than his hands, looking not at Carmen but at the furniture, the floorboards, small hiding places. He believes, with obsessive certainty, that gold--Republican gold, sent here for safekeeping--is hidden somewhere in these rooms. That gold, not the children or the ideals of the Republic, is what truly matters to him.

Carmen knows there is gold. She and Casares have part of the Republican treasury stored at the orphanage to support the cause, useless now that their side is losing. They hide it carefully, trusting in secrecy more than in any illusions about victory. The precise hiding place is their secret, one they guard even from each other with a certain distance, each knowing and not knowing in overlapping ways.

For the boys, the bomb in the courtyard is the center of their fear and bravado. They dare each other to touch it, to put their ears to its hull to hear the clockwork ticking. The metal is warm by day, cold by night. Adults tell them the bomb has been defused, but the fuse still hums faintly, a relentless reminder that death might come without warning.

Jaime tests Carlos with little torments: taking his belongings, mocking his father's death, jabbing him in the ribs. But Carlos has some quiet courage. He refuses to cry, refuses to tell on anyone. One night, there is an initiation game. The boys dare Carlos to sneak, alone, through the dark corridors to the kitchen and fetch a jug of water. He must pass the shadowed courtyard and the looming bomb, and he must go near the storage rooms in the lower level, where no one wants to go after dark.

Carlos accepts, because he would rather confront fear than humiliation. The orphanage after lights-out is a maze of black hallways and echoing footsteps. Floorboards creak, old stone settles with faint groans. He carries a candle, its flame trembling, throwing huge, trembling shadows on the walls.

He passes the bomb, now just a more complete darkness against the starless sky. The ticking is loud to him in the silence, like a second heartbeat. He tells himself it is only metal, only a machine. Beyond it, the air grows cooler. He descends a short flight of stairs into the basement, toward the cistern and storage area. There, he feels it: a presence behind him, not seen but sensed, like the prickling of hair on his neck.

In the gloom by a far wall, Carlos sees him clearly for the first time: Santi's ghost.

Santi appears as a small boy, about his age, with soaked hair, skin the color of old wax, and a terrible wound on his head. From that wound, blood has not stopped flowing, but it floats around his face in reddish tendrils, as if underwater. His eyes are glassy, dark, filled with sorrow older than his years. The edges of his figure blur, smokelike, and from his body, dust motes drift upward, or perhaps they are bubbles rising slowly in invisible water. He opens his mouth as if to speak, but only a long, low sigh escapes, like air escaping a lung that has been held too long beneath the surface.

In a cracked, whispering voice, he finally forms words: "Muchos de vosotros moriréis. Many of you will die."

Carlos freezes, terror crushing his chest. The candle nearly slips from his hand. Another sound erupts--a clatter, a door creaking, movement in the dark. He runs. Through the corridor, up the stairs, into the courtyard, the air cold and vast. But before he can get far, a hand snatches his arm, strong fingers digging into his flesh.

It is Jacinto.

Jacinto's face looms in the night, anger and curiosity mixed. "What are you doing out here?" he snarls. He drags Carlos back inside, unceremoniously hauling him through the halls.

The next morning at breakfast, Dr. Casares stands at the head of the table and demands the truth. Someone snuck out with Carlos, or encouraged him, and Casares insists on knowing who. Carlos looks at Jaime, at the boys watching him, then at the doctor. He swallows and says nothing. When pressed, he takes the blame entirely, refusing to name accomplices. For this, he is punished--made to stand before the class, perhaps denied some small luxuries--but among the boys, something shifts. He has passed an unspoken test of loyalty.

Later, near the cistern under the chapel, an enclosed underground reservoir with still, black water, Jaime confronts him. This is a central place of dread for the children. The air around the cistern smells of damp stone and algae; the surface is opaque and seemingly bottomless. Heavy beams cross overhead, and the sound of dripping echoes endlessly.

Jaime and a few of the boys had taken to collecting slugs around the cistern, using it as a hideout and secret meeting place. It was during one of these times that the real tragedy unfolded, and only Jaime lived to remember it.

He finally tells Carlos the truth.

On the night the bomb fell into the courtyard, he and Santi had been by the cistern. They were just boys then, more worried about slugs than politics or war. They heard noise from the storage room connected to the cistern area--a clank of metal, a muttered curse. Peering around a doorway, they saw Jacinto at a safe, trying to force it open. This safe contained the gold entrusted to the orphanage by the Republican forces. Jacinto, consumed by greed and convinced that this gold could buy his escape and future, had been secretly searching for it for some time.

Jaime, frightened, ducked into hiding. Santi, slower, was caught.

Jacinto turned on Santi like a predator. He grabbed the boy, shook him, hissed that if Santi told anyone what he had seen--if he betrayed his secret--terrible things would happen. Santi, terrified, might have tried to pull away, might have said he wouldn't speak. The details blur in Jaime's memories, but one thing stands out: in anger, Jacinto shoved Santi violently against a stone wall.

The boy's head struck the rock with a sickening thud. His eyes remained open, but they went unfocused. A dark fracture appeared on his skull, and blood ran down his face. He slid to the ground, body shuddering, then going limp. He did not scream. The shock silenced him. His breathing became shallow; he was in a kind of stunned half-death.

Panic seized Jacinto. He tried to shake Santi awake, but the boy only gasped weakly. The caretaker realized what he had done--not fully meaning to kill, but having done mortal harm. In fear of discovery, fear of scandal, of losing his position and his chance at the gold, Jacinto decided not to call for help. Instead, he acted quickly and brutally.

He took stones and ropes, tied them around Santi's small body, securing them at his ankles and chest. Jaime watched from the shadows, shaking, unable to move or speak. Jacinto dragged Santi to the edge of the cistern, the boy perhaps still barely alive, and pushed him into the black water.

There was a splash, a brief flurry of bubbles, then silence. The stones dragged Santi down into the depths, where the darkness and weight extinguished his last breath. His body settled among the silt and whatever else lay at the bottom, unseen by living eyes.

Jaime stayed hidden until Jacinto, cursing under his breath, left the cistern area. When the caretaker was gone, Jaime stumbled out, horror-stricken. He ran up into the courtyard, lungs burning, mind spinning with what he had witnessed. And as he stood there, the night ripped open with a new violence: a bomb whistled down from the sky and slammed into the courtyard just a few feet away from him, burying its nose in the ground and scattering dirt and debris. But it did not explode. It simply stood there, smoking, humming with a deadly promise, its unexploded shell now part of the orphanage's landscape.

From that night on, Santi went missing, and a ghost appeared. The children whispered that the lost boy now haunted the cistern, that his death and the falling bomb were somehow linked. The unexploded bomb, like Santi's spirit, was a wound that had never fully burst. Jaime, carrying the memory alone, grew hard, cruel even, his fear calcifying into hatred for Jacinto.

Now, telling Carlos all this by the cistern, Jaime's tough façade flickers. His voice shakes. He confesses that he once was too afraid to speak up, too afraid to stand against Jacinto. Then he says, with a force born of years of guilt, that he is no longer afraid. If Jacinto ever returns after leaving this place, Jaime vows, he will kill him.

Carlos listens, the image of Santi drowning merging with the ghost he has seen. The boy in the water, the boy in the hallway, the sighing spirit who said, "Many of you will die"--they are all the same. Santi is not merely a story to frighten children; he is a murdered child, a secret preserved in stagnant water.

Meanwhile, above ground, the adult world tightens around the orphanage.

One day, Dr. Casares sees, in the distance, that Ayala, a Republican ally who knows about the gold, has been captured by Nationalist forces. Casares understands immediately what this means. Under torture, Ayala might reveal that the orphanage holds treasure. The Nationalists, victorious and vengeful, would come. They would not spare anyone.

Casares goes to Carmen. In a room filled with the late afternoon light, dust floating like the ghost's motes, he shares his fear. Ayala will be interrogated. The gold will be discovered. They cannot keep the children here; it is too dangerous. They must evacuate the orphanage, send the boys away to wherever may still be safe or at least unknown.

Carmen knows he is right. The war is almost over; the Republic is defeated. Their ideals have been crushed. Their one remaining duty is to keep these children alive, to give them some chance, however slim, at a future not defined by execution walls and mass graves. She agrees: they must prepare to leave, to hide the gold or abandon it, to scatter before the victors arrive.

But the walls have ears, and Jacinto overhears their conversation.

He is standing just beyond the door, listening. When he hears the words "evacuate" and "gold," his knuckles whiten. The prospect of the gold being hidden again, moved beyond his reach, or taken away by politicians or soldiers is intolerable to him. The orphanage is his prison, his remembered humiliation; he has convinced himself that the gold is the key to unlocking that prison. He will not allow it to slip away.

Jacinto storms into the room, face flushed with barely contained fury. He confronts Carmen, demanding to know where the gold is, insisting that he deserves it more than anyone. In front of Dr. Casares, he crudely refers to his affair with Carmen, emphasizing that they have shared a bed, that he has been inside her room and her body, as if this grants him some right to the orphanage's secrets. The words are designed to humiliate both Carmen and Casares.

The doctor's face, usually composed, crumples into rage and hurt. For him, Carmen was something like a sacred love, chaste and unconsummated but deep. To hear Jacinto speak of her as a conquest, and to realize the affair fully, breaks something in him. Anger he rarely shows flares. With trembling hands, he picks up a gun--one of the few they keep for protection--and points it at Jacinto.

"Get out," Casares says, voice iron. He holds Jacinto at gunpoint, ordering him to leave the orphanage immediately. Carmen stands aside, shocked, perhaps a little ashamed, but she does not defend Jacinto. The janitor, though stronger and younger, recognizes the seriousness in Casares's eyes, the knowledge that the older man will shoot if pressed. Jacinto backs away, face tight with thwarted greed and humiliation. He leaves, but the look he gives the orphanage as he walks out is not of someone defeated; it is of someone plotting.

The staff and children, rattled by the confrontation and terrified by the approaching Nationalist victory, begin to make preparations. Carmen and Casares quietly arrange for the boys to be moved. Conchita, torn between her lingering feelings for Jacinto and her loyalty to the orphanage, notices a change in the air--a sense that something terrible is coming.

Jacinto, now outside and cut off, will not accept defeat.

That night, or perhaps the next--it is hard to tell hours clearly in a place where fear compresses time--Jacinto returns. He does not come quietly. He comes with gasoline.

In the deep hours of darkness, as the boys sleep and the adults are scattered in their rooms, Jacinto moves like a shadow through the orphanage. He carries cans of fuel, sloshing it along corridors, around support beams, near doors and windows. The smell of gasoline seeps into the air. He is not thinking of the children as lives but as obstacles, witnesses, weights tying him to a past he hates.

Someone stirs. There is an alarm, half-formed shouts. But before any organized resistance can form, Jacinto strikes a match and sets the orphanage on fire.

Flames leap up with terrifying speed, eating into old, dry wood. Curtains ignite, sending black, oily smoke pouring through hallways. Boys cough awake to find their dormitory filling with heat and fumes. They scream, stumble from their beds, run in confusion. Conchita shouts orders, Carmen limps into the chaos, Casares grabs the gun again, and the bomb in the courtyard watches impassively.

The fire is not just an act of vengeance; it is Jacinto's attempt to flush out the gold's hiding place, to force the staff to reveal it or to destroy the building so he can search the ruins later.

As smoke thickens, some of the boys and staff do not make it. Though their names are not all spoken, their small bodies fall amid beams and embers, overcome by flames and suffocation. The fire claims unnamed children, casualties of Jacinto's greed and the war's indifference. In a sense, these are the "many" Santi had foretold.

In the chaos, Conchita finds Jacinto and, in a desperate bid to stop him, she picks up a gun or a weapon and shoots him, wounding him. The bullet catches him but does not kill him; it's a glancing, painful injury. Jacinto, enraged, flees into the night, leaving the building to burn and collapse as much as it can.

Inside, Dr. Casares does what he can. He ushers boys toward safer rooms, slams doors against the fire, coughs until his lungs feel like they'll tear. In the process--or perhaps later during the aftermath--he sustains injuries, from collapsing beams or from smoke inhalation. Ultimately, Dr. Casares is mortally wounded. Eventually, he withdraws to a room where a window looks out over the ravaged courtyard, a rifle or pistol in his lap. There, he sits by the window and dies, quietly, the weapon resting across his knees, at some unattended hour that will never be recorded.

In the morning light or some similar gray hour, the orphanage stands partially gutted, its walls blackened, interior rooms destroyed. But it is not entirely razed; part of the structure remains, wounded but standing, like the boys themselves. The great bomb still sticks up from the courtyard, inexplicably untouched by the flames, continuing its slow mechanical ticking, the fuse of history that refuses to burn out.

The boys who survived, including Carlos and Jaime, stare at the ruins in shock. Carmen has also been gravely injured--she was caught amid falling debris or close to the worst of the flames. She lies in a bed or on a mattress, pale, her wooden leg set aside. She knows she is dying. Conchita is torn between staying and seeking outside help.

Jaime, hardened further by the deaths of his friends and by what Jacinto has done yet again, swears aloud that if Jacinto returns, he will kill him. The vow takes on the weight of destiny.

Jacinto, meanwhile, nurses his wound elsewhere, his fury stoked rather than quenched. The fire did not get him the gold; it only destroyed the building and killed children. He must try again, more directly.

Recognizing the urgency of their situation, and knowing that neither Franco's forces nor Jacinto will spare them, Carmen and Conchita talk. Conchita volunteers to walk to the nearest town for help or transport, to alert sympathetic contacts who might aid in evacuating the remaining children. The distance is long across empty, war-torn land, but she is determined. Her relationship with Jacinto, already fractured by his violence and greed, is now broken. She has chosen her side.

She sets out alone, the sun baking the hard earth, carrying little more than resolve. The landscape is empty of obvious danger, but the war has filled every road with the possibility of death.

On that road, she encounters Jacinto again.

He is not alone. He is accompanied by two associates, rough men he has enlisted or bribed to help him return to the orphanage and claim the gold. They drive in a car, raising a plume of dust, and they slow when they see Conchita walking.

They stop. Jacinto steps out, his face smeared with soot, his wound bandaged but still raw. He approaches Conchita with a cold, deliberate stride. In his hand, out of sight at first, he carries a knife.

Conchita faces him, fear flickering in her eyes but not overwhelming her. She knows the man he is now. Jacinto, with a mocking calm, threatens her, ordering her to apologize for shooting him. He wants her submission more than he needs her silence. He believes that if she fears him, she might still be useful or at least will die knowing he dominated her.

But Conchita refuses. She looks him in the eye and says she is not scared of him. She will not apologize. Her courage in that moment is perhaps the bravest thing she has ever done.

Jacinto's mouth tightens. Without further argument, he steps forward and stabs her.

The blade slides into her, once, twice, again, as fury and wounded pride guide his hand. She gasps, blood blooming on her dress, eyes wide with pain and disbelief, then they soften as life leaves her. The two associates, watching, are unsettled but say nothing; death is cheap in these years.

Conchita collapses by the roadside, her blood soaking into the dust. Jacinto kills her, and her body is left there in the open land, one more anonymous corpse in a country littered with them. Her death severs the last romantic tie Jacinto had to anyone in the orphanage. From this point, he is entirely an enemy.

Back at the ruined orphanage, Carlos has another encounter with Santi's ghost. By now, he has heard from Jaime what really happened the night Santi died. The knowledge changes his fear into something more complex. When he sees Santi--the damp boy with the cracked skull and trailing blood--standing near the cistern or in a hallway, he no longer screams. Instead, he approaches cautiously, heart still pounding but not with pure terror.

Santi's ghost is quieter now, less a random wraith and more a purposeful presence. He seems bound to the cistern, to the places where he died and where his body remains. The water of the cistern is like a mirror and like a portal; when Santi appears, it trembles.

Carlos speaks to him. He assures Santi he knows about Jacinto, about the murder and the stones and the water. Santi's eyes, lifeless yet full of pain, fix on him. The ghost's whispering voice says only what matters now: he wants revenge. He wants Jacinto.

Softly, Santi makes his demand: Carlos must bring Jacinto to him.

Carlos, trembling but resolute, agrees. The boy, who has lost his father to the war and his friends to fire, recognizes that the world is not governed by fairness. If justice exists, it might be this: the living child acting as bridge between the murderer and the murdered. The ghost's warning--"Many of you will die"--has already begun to come true. Now, perhaps, its final fulfillment will end the haunting.

At the same time, Jaime and the surviving boys--angry, frightened, but no longer paralyzed--come to a grim realization. Jacinto will return for the gold. When he does, he will kill them all to leave no witnesses and no obstacles. They cannot count on adults; Carmen is dying, Casares is… strangely absent, and Conchita is gone. The children are alone.

But they are many, and Jacinto is one man.

Jaime, recalling his vow and filled with the need to atone for his silence about Santi's death, steps into a leadership role. He tells the boys they must fight back. They will not wait quietly to be slaughtered; they will turn the orphanage itself into a weapon.

They gather in a room--perhaps the same cistern room or a remaining classroom--and begin fashioning weapons from simple materials: sharpened sticks, pieces of broken glass tied to wooden handles, makeshift spears, club-like tools. Their hands, always used for chores and play, now become hands that plan murder--or justice, depending on how one sees it.

They speak in low voices, fear mixing with a strange, bitter excitement. Jaime's eyes burn. Carlos, quiet but firm, helps, though he holds inside himself the secret pact with Santi's ghost. The plan is forming on two levels: the boys' worldly resistance and the ghost's supernatural vengeance, converging on Jacinto.

Then Jacinto returns, just as everyone knew he would.

He arrives again with his two associates, the same men who watched him kill Conchita. They come in a car, armed and determined, and drive into the courtyard where the bomb still stands. They enter the orphanage, weapons and violent intent in hand.

Inside, there is less panic this time and more grim awareness. The orphans are quickly imprisoned in one room by Jacinto and his men, locked in together like animals awaiting slaughter. The associates begin to search the orphanage for the gold, tearing apart walls, overturning furniture, cursing as they find nothing. Jacinto, with knowledge gained from his intimate familiarity with Carmen's habits and belongings, searches more cleverly.

Carmen, already badly injured from the fire, can barely move. Her wooden leg is set aside; she is weak, feverish. Jacinto confronts her one last time, demanding the gold, growling that everything that is happening--the ruined orphanage, the dead children--is her fault for keeping it from him. Carmen, perhaps resigned to death, does not yield the secret easily. But Jacinto, rifling through her personal belongings, finally discovers it.

The gold has been hidden in a secret compartment inside Carmen's wooden prosthetic leg. It is a cruelly fitting place--a hollow limb that helped her stand, now revealed as a container of cold, hard coins.

Jacinto breaks open the leg, splintering wood, and there it is: shining, heavy, real. He scoops up the coins, his eyes feverish with triumph. To him, this is salvation. It is the price of passage out of Spain, out of poverty, out of being the nobody orphan boy he once was. He stuffs the gold into sacks or pockets, weighing down his body with wealth.

His two associates, however, have grown impatient and wary. The building is haunted by more than ghosts now; it reeks of betrayal and death. They press Jacinto for their share or want to leave. He snarls, greed making him unwilling to divide his treasure. Tension escalates. In the end, the two men abandon him, leaving him alone in the burned-out orphanage with the children and the gold. The alliance dissolves into suspicion and fear. They take the car and go, or they slip away on foot, deciding that any gold under these conditions is not worth their lives.

Jacinto doesn't care. He has the gold. He has a gun. And he has a plan: once he has secured his treasure and taken what he wants, he will kill the children to erase all witnesses. He moves through the corridors toward the room where the boys are locked, testing the weight of the coins on his hips, every step echoing.

In that locked room, the boys hear him coming, the steps of their executioner. Panic crackles. They clutch their makeshift weapons, but the door is bolted from the outside. There is nowhere to go.

Then something impossible happens.

The ghost of Dr. Casares appears.

He stands at the doorway, insubstantial yet clear enough to see: the old man with his beard and sad eyes, now no longer breathing, no longer among the living. He died earlier, quietly, but has not left. Like Santi, he is a presence caught between worlds, held here by unfinished duty.

He reaches toward the lock. Perhaps the metal corrodes under his touch, or the bolt slides back on its own. The door unlocks, swinging open. In the hallway beyond, no one stands. But on the floor near the threshold lies a monogrammed handkerchief, one of Casares's personal items, proof that his spirit has intervened.

Carlos, seeing this, understands that they are not alone. The dead are on their side.

The boys spill out of the room, hearts pounding, weapons clenched. Jaime raises his makeshift spear; Carlos clutches a sharpened stick or shard of glass. They move as one, a little army of ragged children, their bare feet silent on the stone floor.

They make their way to the cellar where the cistern lies, because they know Jacinto will pass there or because Carlos understands that Santi wants Jacinto brought to him in that place. The air is thick with dampness and old smoke. The surface of the cistern is a black circle in the floor, like a pupil staring up at the ceiling.

Jacinto, hearing something, heads down into the cellar, gun in hand, gold heavy in his pockets. He keeps one hand on the wall to steady himself; the recent wound from Conchita's bullet still aches, and smoke from the earlier fire lingers in his lungs. He thinks the children are still locked away. He thinks he controls the ground he walks on.

He is wrong.

From the shadows, the boys attack.

They surge forward, small bodies suddenly feral. Their sharpened sticks and glass-tipped weapons plunge into him. Stabs land in his sides, his back, his arms. He tries to raise the gun, to fire, but there are too many of them, and they are too close. Their rage is wordless, built from years of bullying, from Santi's murder, from the fire and the deaths, from the war that has made them orphans.

Jacinto cries out, a raw, animal sound. He staggers, blood spilling from multiple wounds. The boys do not stop. Jaime, in particular, drives his weapon deep, the vow to kill Jacinto fulfilled in sharp, jerking motions. In those moments, they are executioners, not children.

The struggle lurches closer and closer to the edge of the cistern. Jacinto's foot slips on damp stone. For a moment, he teeters, arms windmilling, the gold coins in his pockets clinking heavily.

Then the boys push him.

Jacinto falls into the cistern, arms flailing, a flash of shock on his face. He hits the water with a splash that soaks the nearest stones, then disappears beneath the surface. For a second, there is only churning bubbles. Then his head breaks through again. He gasps, eyes wild, arms thrashing.

The gold that was his dream now betrays him. The coins weigh him down, dragging at his belt and pockets, pulling his legs and torso toward the cold depths. He struggles to tread water, but his strength is draining, and blood seeps from his wounds into the cistern, darkening the surface.

From the boys' vantage point above, the scene is terrible and mesmerizing. They watch as Jacinto, the man who once towered over them with casual cruelty, now churns in terror like a caught animal. They do not reach for him. Justice, or vengeance, is unfolding according to a deeper script.

Below, in the greenish darkness of the cistern, something moves.

The water around Jacinto ripples in a way that is not natural. From the depths, up toward his flailing legs, rises Santi.

The ghost boy appears beneath the surface more clearly than ever. His true domain is water; here, his edges are sharp, his hair floating around his face, his broken skull oozing endless tendrils of blood that diffuse slowly into the cistern. His eyes fix on Jacinto with a gaze that is simultaneously empty and full of patient hatred.

Jacinto feels something seize his ankle--cold, small hands, implacable. He jerks, tries to kick free, but the grip tightens. Bubbles stream from his mouth as he screams underwater. He reaches for the edge of the cistern, fingers scraping stone, but he is dragged down.

Santi pulls him, inexorably, toward the bottom where the ghost's own body lies tied with stones. Jacinto's struggles become weaker, then frantic, then slow. The gold coins clink one last time. The surface of the water stills, and only a faint swirl of blood remains.

Jacinto dies, drowned by Santi's ghost, his last breath stolen by the child he murdered. The cistern becomes their shared tomb, the place where injustice is finally met with retribution. This is not the justice of any court or army; it is the justice of wounded children and restless spirits.

Above, on the stone rim, the boys are silent. Jaime exhales shakily. Carlos feels a strange mixture of triumph and sorrow. They have killed a man. They have avenged a friend. The war inside the orphanage is over.

Somewhere nearby, the unexploded bomb in the courtyard continues to tick softly, still unexploded, as if to say that while one threat has ended, larger ones remain.

In the wrecked interior, Carmen finally succumbs to her injuries off-screen, her body too weak to go on. Her death is quiet and unheralded; another casualty of the war's stray shrapnel. She leaves no ghost that we see; perhaps she is too tired to linger.

Dr. Casares, already dead, remains manifest only briefly, long enough to watch over the children he could not protect in life. His presence is gentle, a counterpoint to Santi's vengeful force.

With Jacinto gone and the building damaged beyond repair, nothing keeps the children at the orphanage anymore. It is no longer a refuge; it is a ruin. The outside world, dangerous as it is, becomes their only option.

They gather their meager belongings--clothes, a few books, perhaps a drawing or two from Jaime's sketchbook. They step into the courtyard, past the bomb that never exploded, under the vast, indifferent sky. There is no adult to lead them now. They are a small procession of orphans, walking into a future that may hold prison, poverty, or worse, but at least is theirs to face.

Before they leave, Carlos turns back once more. In a doorway, half in shadow, he sees Dr. Casares's ghost standing, watching them. The old doctor's face is calm, sad, proud. He cannot go with them, but he can oversee their departure.

Carlos approaches him within the range that living and dead can share for a moment. Eyes brimming, he tearfully says goodbye. It is not just a farewell to the man; it is a farewell to childhood, to the illusions of safety, to the orphanage as he first knew it.

Casares's ghost does not speak, or if he does, the words are more felt than heard. He might tell Carlos to be brave, to remember, to live. The boy nods, understanding in his bones even if he doesn't have language for it yet. Then he turns and joins Jaime and the others.

As they walk away, Casares's specter remains in the doorway, a solitary figure framed by blackened stone. He watches the boys become small in the distance, their silhouettes wavering in the heat on the horizon. He is a ghost who remembers being alive, bound less by tragedy than by love and regret.

Behind him lie the charred halls, the cistern holding the bodies of Santi and Jacinto, and the bomb that never exploded. Ahead of the children stretches a Spain reshaped by fascist victory, where they will have to navigate hunger, fear, and the fading memory of the ideals their parents died for.

The last image belongs to the orphans: Carlos, Jaime, and the surviving boys walking away from the orphanage toward the town, backs to the camera, dust rising around their feet. No one rescues them; no cavalry appears. They simply go, carrying their ghosts within them.

The earlier question returns like an echo: What is a ghost? A tragedy doomed to repeat itself. A moment of pain endlessly replayed. Or perhaps a child left behind in a war, walking away from a place of death, not knowing if he is leaving the ghost or if he is the one who will haunt the future.

What is the ending?

In the ending of "The Devil's Backbone," Carlos confronts the ghost of Santi, who reveals the truth about his death. The orphanage is set ablaze, and the remaining children escape. In the chaos, the adult characters face their own fates, with the war's brutality culminating in a tragic conclusion.

As the film nears its end, the atmosphere in the orphanage grows increasingly tense. The children, led by Carlos, have learned about the ghost of Santi, a boy who died under mysterious circumstances. Carlos, feeling a deep connection to Santi, seeks to uncover the truth behind his death. The ghost appears to Carlos, revealing that he was murdered by Jacinto, the caretaker of the orphanage, who is driven by greed and a desire for power.

In a pivotal scene, Carlos confronts Jacinto, who has become increasingly unstable and violent. The confrontation escalates, and Jacinto's true nature is revealed as he lashes out at the children and the orphanage itself. The tension reaches a breaking point when Jacinto, in a fit of rage, sets the orphanage on fire, believing that he can erase the past and the ghosts that haunt him.

As the flames engulf the building, the children, led by Carlos and the other orphans, make a desperate escape. They navigate through the smoke and chaos, their faces filled with fear and determination. The fire symbolizes the destruction of innocence and the harsh realities of war that have invaded their lives.

In the midst of the chaos, the fate of the main characters unfolds. Jacinto, consumed by his own greed and violence, meets a tragic end as he is confronted by the ghosts of his past, including Santi. The flames claim him, a fitting punishment for his actions. Meanwhile, the children manage to escape the burning orphanage, but they are left to grapple with the trauma of their experiences and the loss of their home.

Carlos, having witnessed the horrors of both the living and the dead, emerges from the fire with a newfound understanding of the world around him. He carries the weight of Santi's story and the memories of the orphanage, forever changed by the events that transpired. The film closes on a haunting note, emphasizing the impact of war on innocence and the lingering presence of the past, as the children look back at the flames consuming their home, a symbol of both loss and survival.

Is there a post-credit scene?

The Devil's Backbone, directed by Guillermo del Toro and released in 2001, does not have a post-credit scene. The film concludes with a haunting and poignant ending that encapsulates its themes of loss, memory, and the lingering effects of trauma. After the climactic events, the story leaves viewers with a sense of unresolved tension and emotional weight, focusing on the fates of the characters rather than providing additional scenes or resolutions in the credits. The film's conclusion is powerful enough to stand on its own, emphasizing the impact of the past on the present.

What is the significance of the ghost of Santi in the story?

The ghost of Santi serves as a haunting presence that embodies the trauma and unresolved issues of the Spanish Civil War. His appearance is tied to the dark secrets of the orphanage and the past of the characters, particularly Carlos, who is drawn to Santi's plight. Santi's ghost represents the innocence lost during the war and the need for truth and reconciliation.

How does Carlos's arrival at the orphanage affect the other children?

Carlos's arrival at the orphanage introduces a new dynamic among the children. Initially, they are wary of him, but as he befriends them, he becomes a source of hope and courage. His curiosity about Santi and the mysteries of the orphanage leads the other children to confront their fears and the reality of their situation, ultimately uniting them against the threats they face.

What role does the character of Jacinto play in the orphanage?

Jacinto is a complex character who embodies both the caretaker and the antagonist. He is a former orphan who returns to the orphanage with a sense of entitlement and greed, seeking to exploit the situation for his own gain. His violent and selfish nature contrasts sharply with the innocence of the children, and his actions drive much of the tension in the story, revealing the darker side of human nature.

What is the relationship between Carmen and the other characters in the orphanage?

Carmen, the matron of the orphanage, is a nurturing yet conflicted figure. She is protective of the children and deeply affected by the war's impact on their lives. Her relationship with Jacinto is fraught with tension, as she is aware of his dangerous tendencies but feels trapped by her circumstances. Carmen's emotional struggles highlight her resilience and the sacrifices she makes for the sake of the children.

How does the setting of the orphanage contribute to the film's atmosphere?

The orphanage itself is a character in the film, with its crumbling architecture and eerie ambiance creating a sense of isolation and foreboding. The dark, shadowy corridors and the haunting presence of the ghost contribute to the film's atmosphere of dread and mystery. The setting reflects the emotional states of the characters, serving as a backdrop for their fears, secrets, and the lingering effects of the war.

Is this family friendly?

"The Devil's Backbone," directed by Guillermo del Toro, is a haunting tale set during the Spanish Civil War. While it is a visually stunning film with rich storytelling, it contains several elements that may not be suitable for children or sensitive viewers.

-

Themes of War and Violence: The backdrop of the Spanish Civil War introduces themes of conflict, loss, and the impact of violence on children and families. There are references to the brutality of war, which may be distressing.

-

Ghosts and Supernatural Elements: The film features a ghostly presence and supernatural occurrences that can be frightening. The ghost of a child, in particular, is central to the story and may evoke fear.

-

Death and Grief: The narrative explores heavy themes of death, abandonment, and the emotional turmoil associated with loss. Characters grapple with grief, which can be intense and unsettling.

-

Child Endangerment: The children in the film face various dangers, both from the supernatural and from the adult characters, creating a sense of tension and fear for their safety.

-

Mature Themes: There are discussions and implications of betrayal, jealousy, and moral ambiguity among the characters, which may be complex for younger audiences to understand.

Overall, while "The Devil's Backbone" is a beautifully crafted film, its mature themes and unsettling imagery may not be appropriate for younger viewers or those sensitive to such content.