Ask Your Own Question

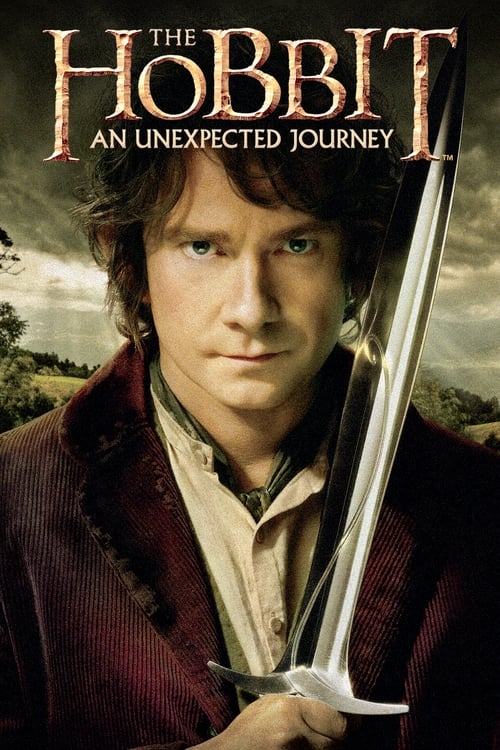

What is the plot?

Old Bilbo Baggins sits alone in Bag End in Hobbiton, the Shire, on the morning of his one hundred and eleventh birthday, the day of the big party that will soon draw half the Shire to his door. The sunlight outside is soft and golden; inside, his round hobbit‑hole is cluttered with papers, maps, and trinkets from a life most of his neighbours imagine has been entirely uneventful. He opens a large, red‑bound volume--the Red Book--and dips his quill. On the first page he writes the title: "There and Back Again, by Bilbo Baggins." He pauses, then adds, "And Hobbiton, by Bilbo Baggins," almost amused at himself.

He begins to write and to narrate, addressing the story to his young cousin and heir, Frodo Baggins. Frodo appears briefly, bustling in and out, talking about party preparations and fireworks, pressing Bilbo to hurry or to hide from the busybodies outside. Frodo leaves, the front door closes, and the hobbit‑hole falls quiet. Bilbo glances, almost guiltily, at a small, unassuming golden ring hidden away among his effects, but he does not mention it, does not write of it yet. Instead, his mind and his words turn east, beyond the borders of the Shire, and many decades back in time.

He writes of the Kingdom under the Mountain: Erebor. In his words and in the unfolding images, the story sweeps away from Bag End to the Lonely Mountain, where King Thrór rules a thriving Dwarven kingdom whose forges burn hot and whose coffers overflow with gold and jewels. The dwarves mine deep beneath the mountain and there they discover one unique gem, pale and radiant: the Arkenstone, the "heart of the mountain." King Thrór gazes at it as though nothing else in the world exists; the more he stares, the more his pride and obsession harden around it.

Under Thrór's rule, Erebor prospers. The City of Dale, spread at the base of the mountain along the River Running, grows rich on trade with the dwarves. Men in fine clothes stroll busy markets filled with toys, weapons, food, and marvels of dwarven craft. Thrór's son Thráin II stands at his side, and the young prince Thorin, grandson to Thrór, strides through the gleaming halls, a proud warrior in training, beloved heir of a mighty line.

Bilbo's voice darkens as he writes: "But pride and greed were their downfall." The shot drifts over overflowing treasure: mounds of gold, jeweled cups, and the brilliant Arkenstone held high above the throne. Far away, something ancient and covetous stirs. Smaug the tremendous, a great fire‑drake, hears of the hoard. He flies out of the north like a storm, a vast shadow against the sky.

Smaug descends upon Dale in midday, and death begins at once. His first blast of dragonfire rips through towers and rooftops, incinerating streets in moments and slaughtering Men of Dale where they stand. Unnamed men and women, merchants and guards, children and elders--all are burned and crushed as buildings explode and tumble beneath his wings and claws. Those who flee are swept aside by fire or buried under stone. The prologue does not give them names, but it makes their deaths clear and terrible: they are the first victims of Smaug's assault, killed by fire and falling ruin, by his rage and greed.

Then Smaug turns his fury upon Erebor. He smashes through the great front gate, tearing apart stonework that seemed eternal. Dwarves rush to arms, but dragonfire scours the front halls; warriors die in blazing waves, their bodies hurled aside or buried under collapsing arches. The air is filled with screams and roaring; the once‑bright kingdom becomes a furnace. Smaug drives ever inward, chasing the king and his people away from their riches, until he reaches the treasure chamber itself and throws himself upon it, rolling in the gold and jewels, his enormous body coiling around the Arkenstone.

Outside, young Thorin rallies those he can. He tries to hold the great gate, leading a desperate stand against the dragon's fury, but even he cannot withstand the onslaught. The dwarves are forced to flee into the open, abandoning gold, home, everything. Behind them, the Mountain belches smoke and flame.

On the ridges above, the Elvenking Thranduil arrives with a host of armed Elves. For a moment, Thorin believes there is hope. The dwarves look up at the tall, cold figure on the stag, his warriors ranked in shimmering armour. But Thranduil surveys the ruined valley, the burning city, the raging dragon occupying the Mountain--and then he turns away. The Elves withdraw without raising a bow, without coming to the dwarves' aid. Bilbo's narration states what this moment does to Thorin's heart: it forges in him an unyielding, lifelong hatred of Elves.

In the chaos that follows, as the exiles wander homeless, Thrór and Thráin II are lost to their people. Their specific fates are not yet fully recounted here, but the dwarves' line of kings seems to end in exile and madness. Many more dwarves die on the long road east and south, nameless casualties of hunger, hardship, and marauding enemies implied in the narration.

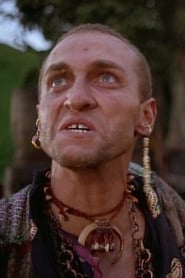

The scene shifts again, now to another battle in another place and time that Bilbo writes down: the field of Azanulbizar before the gates of Moria, in the year 2799 of the Third Age, where Thorin's grandfather meets his true doom. On the rocky slope outside the Dwarven kingdom of Moria, King Thrór leads his people into war against the Orcs of the Misty Mountains. Steel clashes against crude iron in brutal, close‑quarters combat. There, towering above his kin, the pale Orc war‑chief Azog the Defiler strides forward. He is a massive figure, scarred and cruel, his white skin marked with blue runes. In his hand he wields a huge mace, and upon his standard, severed dwarf heads are mounted.

In the thick of battle, Azog meets King Thrór and cuts him down. The film's flashback makes clear: Thrór is beheaded, his life ended on that battlefield by Azog's hand, his head presented as a trophy to break the dwarves' spirit. Azog's slaughter does not stop there; he kills many dwarves that day, maiming and butchering them to make an example of their royal line. Thorin, seeing his grandfather's fate, is consumed with fury. During the fighting, he grabs a sturdy oaken branch to use in place of a ruined shield, and with it, and his blade, he presses the attack against Azog. In their clash, Thorin manages to sever Azog's forearm--or hand, as some tellings phrase it--sending the Orc's limb and weapon to the ground. Azog is dragged away by his followers, roaring in hatred, while Thorin, standing battered amid the dead, earns the name Oakenshield. Though the dwarves eventually take the field, they do not reclaim Moria, and the victory is stained with loss.

The quill of old Bilbo slows. He writes that exile became the dwarves' lot, that Thorin Oakenshield and his kin wandered from one poor refuge to another. Then he lifts his head and we are drawn back, finally, to the Shire, and to a time sixty years before the birthday now being prepared. The story tightens in on a single hobbit and a single, unexpected knock on his life.

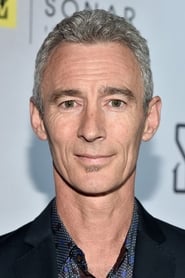

Hobbiton, in those days, is peaceful and green. A much younger Bilbo Baggins, fifty years old, lives alone in Bag End, content in his routines of food, pipe‑weed, and solitary comfort. He is prim, particular, proud of his well‑stocked pantry and tidy larder. On one quiet morning, as he sits outside his front door with his pipe, he sees a tall, grey‑cloaked figure come up the lane. The old wanderer has a staff, a wide‑brimmed hat, and bright eyes under shaggy brows: Gandalf the Grey.

"Good morning," Bilbo says politely, meaning it only as a greeting.

"What do you mean?" Gandalf replies, amused. "Do you wish me a good morning, or mean that it is a good morning whether I want it or not…?" Their banter unsettles Bilbo. Gandalf hints at adventures beyond the borders of the Shire, at dragons and mountains and things that happen to people who step outside their doors. Bilbo insists he wants none of it. Gandalf, however, remembers a little hobbit boy who once leaped from behind hedges looking for excitement; he reveals that he has watched Bilbo since those days, seeing in him a spark of something more than comfort. That quiet revelation--Gandalf's long‑standing interest--means Bilbo has been chosen for this visit, not stumbled upon by chance.

When Gandalf abruptly declares, "I am looking for someone to share in an adventure," Bilbo recoils. No, he is a Baggins of Bag End; adventures are messy, make one late for dinner. He retreats indoors, leaving Gandalf on the doorstep. But as Bilbo shuts the round green door, Gandalf leans forward and scratches a strange mark upon it with the tip of his staff: a secret rune, a signal in the hidden language of dwarves and wizards. It marks this hobbit‑hole as the meeting place for a company that Bilbo does not yet know is coming.

That evening, as twilight deepens over Hobbiton, Bilbo is preparing a quiet supper when there is a knock. He opens the door to a dwarf: Dwalin, bald and tattooed, who pushes past him as though expected, greeting him as "Mr. Baggins" and immediately claiming a seat and an ale. Before Bilbo can process this, another knock: Balin, older and white‑bearded, arrives, equally at home. Soon after, Chipper Fíli and dark‑haired Kíli stride in, all young energy and weapons. Then more--Bifur, Bofur, Bombur, Óin, Glóin, Dori, Nori, Ori--arrive in clumps, each with a different beard, accent, and appetite. They swarm over Bilbo's pantry, pulling out hams, cheese wheels, vegetables, beer, and wine, piling dishes high, singing and laughing as the neat hobbit‑hole becomes a rowdy dwarf‑hall.

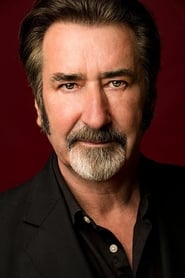

Bilbo is nearly panic‑stricken, racing to save his crockery and protest at every smashed plate or spilled stew. The dwarves barely listen, assuming this is exactly what Gandalf arranged. At last there is another, heavier knock. The room stills. Into the doorway steps Thorin Oakenshield himself, late and stern. His bearing is that of a dispossessed king. When he removes his hood, his dark hair falls around a scarred face; he carries years of exile on his shoulders.

Gandalf finally appears, ducking into the crowded space and revealing that he has called this meeting in Bilbo's home. Around the table, Thorin spreads out a map: the plan is to travel east to the Lonely Mountain, to reclaim Erebor and its treasures from the dragon Smaug who took it from them. They need a burglar to sneak into the mountain, to open doors unseen and scout the dragon's lair. Gandalf has chosen Bilbo for this role, believing--though he does not fully explain why--that a hobbit is well suited to it: small, quiet, overlooked by their enemies. He presents a contract detailing the risks: "incineration, dismemberment," and Bilbo's share--one fourteenth of the treasure. The contract, written in dense dwarvish legalese, is a physical manifestation of their mercenary view of this hobbit; it also, unbeknownst to Bilbo, will bind his fate tightly to theirs.

Bilbo is aghast. A dragon? Risking life and limb? He sputters at Gandalf for his presumption. Thorin is openly dubious, regarding Bilbo as an unnecessary burden, a soft creature unsuited to such a task. The mood shifts when Thorin recounts his own past: the story of Azanulbizar, the beheading of King Thrór by Azog, the severing of Azog's hand, the painful birth of the name Oakenshield. In the flicker of the hearth, dwarven voices soften into that haunting song--"Far over the misty mountains cold…"--a lament for Erebor. As they sing, their deep voices blend with Bilbo's narration in the older time, and something in Bilbo stirs: a sense of the vast world, of loss and longing beyond his door.

Yet when night ends, fear wins. In the morning, Bilbo wakes to find Bag End empty, the dwarves and Gandalf already gone. The house is still, only scattered crumbs and a forgotten bit of contract paper left behind. He stands in his doorway, looking out over the Shire, heart racing. If he stays, nothing will change; if he goes, everything might. Suddenly he grabs the contract, stuffs it into his pocket, and runs. Through Hobbiton's lanes he sprints, calling, "I'm going on an adventure!" as baffled hobbits stare. He catches up with the company at the edge of the Shire, breathless but determined, and signs the contract properly, putting his name to his decision.

Now the story leaves the comforts of Hobbiton. The company travels along the by‑roads of the Shire, past hedgerows and rolling fields, perhaps brushing by the inn called the Green Dragon, though any visit is fleeting and implied rather than lingered upon. Every step is a step away from Bilbo's former life.

Days later, in the wilder lands called the Trollshaws, the company's ponies begin to disappear in the night and rain. Thorin orders a search. Bilbo, eager to prove useful, creeps through the dark woods and stumbles upon a fire. Around it, three enormous trolls--Tom, Bert, and William--argue in coarse, cockney voices about dinner. He sees his companions' ponies tied up in sacks. Steeling himself, Bilbo attempts his first act as burglar: he sneaks up to pick William's pocket. His hands shake; he fumbles. William catches him. In a heartbeat, Bilbo is dangling upside down, face to warty face with a troll who wants to know how best to cook him.

The trolls soon capture the arriving dwarves as well, tossing them into sacks or pinning them under feet, discussing whether to roast, boil, or mince them. Bilbo, finding his wits amid terror, stalls them with talk, arguing about culinary techniques, insisting dwarves must be properly washed and seasoned, that one should never rush such delicate meat. His chatter buys time. Gandalf, watching from the shadows, seizes that time to move behind a boulder. Just as dawn is about to break, he raises his staff and cracks the rock above the trolls' fire. Sunlight pours in like a blade. The trolls turn toward it, howling, and as the first rays of the rising sun strike their skin, they stiffen, their grey flesh hardening into stone. Within moments Tom, Bert, and William are frozen statues, mouths open in mid‑complaint.

Those trolls die there, transformed to stone by the sun. Gandalf's intervention is the cause; the method is the ancient curse that trolls cannot endure daylight. Their stony forms remain, a warning to others and a reminder of Gandalf's timing and power.

Recovering, the company searches the trolls' camp and finds a hidden cave. Within, beyond sacks of plundered goods, they discover three remarkable blades on a stone bench: Glamdring, the long sword Gandalf claims, once the blade of the king of Gondolin; Orcrist, which Thorin takes, later to be known by goblins as the Goblin‑cleaver; and a smaller, finely made Elvish knife that Bilbo shyly takes for himself. He does not yet name it, but this blade will soon earn the name Sting. These blades, of Elvish make, glow blue in the presence of goblins and Orcs, an enchantment that will serve as an early warning throughout their travels.

While Thorin's company moves on from the Trollshaws, elsewhere in Middle‑earth another thread tangles into their fate. To the south, in the forest of Greenwood the Great, a wizard of a different sort lives in a crooked house at Rhosgobel. Radagast the Brown, one of the Istari like Gandalf, tends birds, rabbits, and hedgehogs in a cluttered home overflowing with nests and herbs. He senses a wrongness spreading through the trees: leaves blackening, animals dying from a strange blight. Investigating, he finds giant spiders, unnatural and venomous, and follows the taint to a ruined fortress hidden in the dark woods: Dol Guldur.

Inside Dol Guldur, a presence gathers--the Necromancer, a shadowy figure of swirling darkness and malice. Radagast glimpses him only briefly, but the encounter is enough. He is attacked by wraith‑like forces, and in the struggle he finds and takes a Morgul blade, a cruel, curved dagger that radiates cold evil and is known as a weapon of the Witch‑king of Angmar. Clutching the blade, Radagast flees Dol Guldur in terror, harnessing his rabbit‑drawn sleigh to carry him away. This blade will become his evidence that an ancient darkness, tied to Sauron himself, is rising again.

Later, when Radagast crosses paths with Gandalf and Thorin's company in the wild, he shares his news in breathless, disjointed words. He describes the spiders, the darkness, the Necromancer, and holds out the Morgul blade as proof. At almost the same time, far off, Azog the Defiler hears news of Thorin's movements and places a bounty on his head. Vengeance and profit combine: Azog wants Thorin destroyed.

Soon after leaving the troll cave, the dwarves and Bilbo camp in rough country east of the Shire. Night falls again. A low, distant howling begins. Wargs--huge, wolf‑like beasts--appear, ridden by Orc scouts who have taken up Azog's hunt. Radagast, racing north in his rabbit sled, runs straight through their lines. To save Gandalf and the company, he deliberately draws Wargs and Orcs after him, darting and weaving through the forest so that they chase his swift sled, leaving the dwarves a brief gap. Gandalf uses that opening to lead the company through a narrow stone passage, toward a hidden valley. Orcs and Wargs close behind, jaws snapping, but as the company emerges, riders appear above: Elves of Rivendell, led by Lord Elrond of Imladris.

Elrond and his warriors sweep down, their horses fast, their blades precise. They cut through the pursuing Orcs, driving them off or killing them, forcing any survivors to flee back into the wild. Azog himself is not present in this skirmish; his orders have brought these Orcs to their doom. The dwarves, saved by Elven skill, are less than grateful. Thorin remembers Thranduil's withdrawal from Erebor and hides resentment under curt words. Yet Elrond still offers them the hospitality of Rivendell--the Last Homely House east of the Sea. They accept, grudgingly.

Rivendell lies in a hidden valley, waterfalls streaming down high cliffs, lit by lanterns and starlight. Within its halls, Elves in pale robes move gracefully; music drifts in the air. The contrast with the rough road could not be stronger. Bilbo is entranced. Thorin is wary. The company eats, rests, and more importantly, unrolls Thror's map of the Lonely Mountain before Elrond. Elrond examines it carefully and notes that some runes are not visible in normal light. He leads them outside on the evening of a crescent moon, explaining the lore of moon‑runes: letters that can be read only when the moon is of the same shape and in the same season as when they were written.

Under that particular moon--late spring, though the exact calendar date is not specified--faint letters glow on the map. Elrond reads them aloud. They speak of a secret door on the western side of Erebor and how it may be opened only on Durin's Day, "the last light of Durin's Day will shine upon the keyhole," when the sun sets on the last day of autumn and the moon is in the sky at the same time. This revelation changes everything. The map is no longer just a drawing; it is a set of instructions, a timetable. Miss that single evening at the end of autumn, and the hidden door will remain shut for another year, perhaps forever. Thror's key, which Thorin already bears, now has a lock and a moment.

While the dwarves grumble about Elven food and whisper that they cannot trust these folk, Gandalf seeking broader counsel convenes the White Council in Rivendell. In a sheltered chamber, Lord Elrond meets with Lady Galadriel of Lothlórien, luminous and serene, and Saruman the White, head of their order, imposing in white robes. Gandalf presents Radagast's Morgul blade to them, explaining that this is a dagger of the Witch‑king of Angmar and that it was taken from Dol Guldur, where a being calling himself the Necromancer now dwells. To Gandalf, this is a sign that Sauron, long thought destroyed, may be returning, gathering strength in secret.

Saruman dismisses his fears. The ringwraiths cannot have returned, he insists; their works were ended long ago. He regards Radagast as a foolish eccentric and the dwarves' quest as a reckless distraction, urging Gandalf to put a stop to it. Elrond, more cautious, shares some of Saruman's doubts. Galadriel, however, listens in silence, her gaze on Gandalf. Later, privately, Gandalf confides to her that he anticipated Saruman's opposition; that is why he has already had Thorin's company prepare to leave without him, slipping away quietly while the Council debates. This is one of Gandalf's subtle manipulations: he will stand with the small, determined exiles even if the mighty argue for inaction.

Night passes; the company moves on. The green valleys of Rivendell give way to the harsh slopes of the Misty Mountains. Storm clouds gather. High in the passes, the wind howls with icy teeth. As they cross a narrow ledge, thunder rolls--not all of it from the sky. Across the chasm from them, a hulking form rises: a stone giant, a living mountain throwing boulders at another of its kind in some titanic game or feud. Rocks smash together, shattering into avalanches that tear away parts of the path under the dwarves' feet. For a terrifying moment, the company's ledge proves to be part of one giant's leg; they cling to the slick rock as the colossus steps, almost hurling them into the abyss. By inches they scramble off, wet and shaken, into a small cave they believe will offer shelter from the storm.

Inside the cave, they lay out bedrolls, exhausted. Bilbo, still feeling the sting of Thorin's doubts about his fitness, quietly considers whether he should turn back. He tells Bofur he doesn't feel like he belongs and thinks of the Shire's warm food and simple pleasures. While they argue softly, the floor heaves. The "cave" is a trap: the stone drops away, revealing a chute. The company falls screaming into darkness, right into the hands of goblins.

They land in a vast, torch‑lit cavern, surrounded by a swarm of misshapen goblins. Crude spears prod them towards rickety walkways and bridges. Their weapons are stripped away; Orcrist and Glamdring are taken. Bilbo, flung aside in the confusion, tumbles down a separate fissure, crashing into an even deeper, darker hole. While the dwarves are driven deeper into the goblin realm, Bilbo lies alone, winded.

The goblins march the dwarves and Gandalf--who has been separated for the moment--through a chaotic, vertical city of platforms and chains, all leading to the throne of the Great Goblin, a corpulent, sneering creature festooned with trinkets and flanked by guards. The Great Goblin delights in his catch. He orders their possessions examined. When Orcrist is drawn, it glows blue, and he recoils in horror and rage, recognizing it as the "Goblin‑cleaver," bane of his kind from wars long past. He taunts the dwarves with old grievances, but his tone sharpens when he speaks of recent matters: he tells them that Azog the Defiler has placed a bounty on Thorin Oakenshield's head. In this way the dwarves learn that Azog survived his maiming and has not forgotten them; that his vendetta is active, and his Orcs and Wargs are on their trail. The stakes of their journey rise again: they are not just heading toward danger at the Lonely Mountain; danger is racing after them.

Meanwhile, in the crevice where he fell, Bilbo rouses and gropes about. His hand closes on something small and cold: a simple golden ring lying on the stony floor. He does not know it fell from Gollum's pocket as that creature dragged a stray goblin corpse into the shadows to eat. That stray goblin, unseen by the company, has just died at Gollum's hands, killed by teeth and claws in the dark so that Gollum may feed upon him; his body is food and his death is the prelude to one of the age's great corruptions. But Bilbo only sees a ring. He slips it quietly into his pocket.

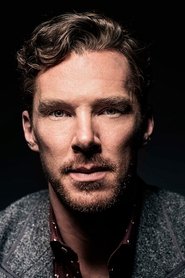

Not long after, Bilbo encounters its former owner. Gollum, pale and skinny, with enormous eyes, confronts him with a mixture of curiosity and hunger. They circle each other in a cavern dominated by an underground lake, the air chill and damp. Bilbo draws his small Elvish blade in fear; Gollum eyes it, then shifts moods, proposing a "game." They will trade riddles. If Bilbo wins, Gollum will show him the way out. If he loses, Gollum will eat him. The stakes are plain: this is a verbal contract with life as the wager.

The riddle‑game begins: classic riddles and strange questions echo back and forth, each more desperate than the last. Bilbo's mind stretches; he reaches for every bit of lore and wordplay he knows. As they play, Gollum absently pats his body for his "Precious" and slowly realizes the ring is gone. Bilbo, for his part, is sweating, terrified. Running out of proper riddles, he blurts, "What have I got in my pocket?" It is not a riddle and not within the agreed rules, but Gollum seizes upon it as the next question, furious and suspicious. He fails to answer correctly and, by the tenuous code of their game, loses.

Gollum's mind leaps to the only explanation: the hobbit has his ring. His fear and anger erupt. He howls and lunges at Bilbo. In the scramble, Bilbo slips the ring onto his finger. The world changes. Gollum sees only emptiness where Bilbo stood; Bilbo sees Gollum twisted and monstrous and hears a distant, whispering distortion of sound. He realizes, through panicked trial, that the ring has made him invisible. Using this power, he evades Gollum's grasp and follows him through the tunnels as the creature, blinded by outrage, races toward the exit, hoping to intercept the "thief."

Up in the larger caverns, the Great Goblin's fun is interrupted. Out of the dark, Glamdring flashes: Gandalf has returned to them. With one sweeping strike he cuts down the Great Goblin, killing him where he stands. The goblin's massive body falls from his platform, smashing through walkways and causing chaos. Their leader's death throws the goblin horde into disarray, but also into frenzied attack. Gandalf drives the dwarves into a panicked escape, chopping and blasting a path through tunnels crowded with shrieking goblins. Dori carries Ori; Bombur stumbles; they all fight and flee. No dwarf dies in this melee, but countless goblins fall, slashed or shoved into chasms as the company barrels through. The Great Goblin's death is total and decisive; Gandalf's blade Glamdring is the instrument.

Bilbo, still invisible, reaches the tunnel mouth ahead of Gollum and finds sunlight beyond. Gollum, sensing him, crouches in the passage, sobbing and muttering, his mind breaking anew as he realizes the ring--his Precious--is gone. Bilbo, standing inches away, raises his sword to strike. He could kill Gollum in that moment and end one pitiful life that has done much harm. Yet as he looks into Gollum's eyes, he sees not only malice but also wretched despair. Pity fills him. He lowers the blade, spares the creature, and instead leaps over him, sprinting out into the bright, open air. Behind him Gollum collapses, screaming and cursing "Baggins," vowing to hate the name forever.

Outside, the dwarves and Gandalf stumble out of another exit, gasping at the sudden light. They take stock. Bilbo is missing. Thorin is ready to believe he has turned back or fallen, but before despair can settle, Bilbo appears, climbing over a rock, breathing hard, but alive. They demand to know how he escaped. He shrugs, speaks vaguely of losing the goblins, of sneaking past, not mentioning the ring at all. His omission--the choice not to tell them about this golden ring that grants invisibility--is quiet but enormous. It births a secret that will shape the fate of Middle‑earth.

Thorin, still suspicious, asks why Bilbo did not simply go home once free. Bilbo, searching for words, explains that he misses his books and armchair and his garden--but that the dwarves have none of those things. They have only their home to reclaim, and so he will help them. His loyalty and bravery shine through. Gandalf, watching, smiles slightly. Thorin, though unconvinced, can no longer easily dismiss this hobbit.

The company does not get long to rest. As they move eastward into sparse woodland above the Anduin valley, a hunting howl splits the air. Wargs and Orcs, this time led by Azog himself, have found them. The sun is low; shadows are long. From a rise, Azog appears on a great white Warg, his severed arm replaced by a crude iron prosthetic. His hatred burns as hot as on the day Thorin maimed him. He orders the pack forward.

The dwarves run until they are cut off at the edge of a cliff, sheer rock falling away behind them. Gandalf, seeing no way through, orders them up into a group of tall fir trees. They scramble into the branches as Wargs snap at their heels, Orcs hacking at the trunks with torches and blades. Soon, fire licks up the bark. One by one the trees begin to topple, pushed and burned, leaning out over the abyss. The company clumps together on the last tree, its rootball teetering at the cliff's edge, the ground far below, Wargs and Orcs massed all around.

Azog steps forward into the firelight. Thorin sees his ancient enemy and something in him cannot stay in the branches. Ignoring Gandalf's warning, he descends the burning trunk, staggers onto the scorched ground, and draws Orcrist. With a roar he charges Azog. It is an act born of pride and trauma, a desire to finish what he began at Azanulbizar. But this battlefield is not the same. Azog's huge white Warg slams into Thorin before he can land a blow, knocking him aside. Azog advances and, with his Warg and weapon, viciously injures Thorin, beating him down and leaving him unconscious and bleeding on the rock. In that moment, Thorin is as vulnerable as his grandfather was at Moria.

On the leaning tree, the other dwarves watch in horror. Gandalf fights to hold the Orcs at bay with flame and sword, but their position is hopeless. Bilbo, who moments before thought only of survival, now sees the fallen dwarf who once scorned him. Something has changed in the hobbit. He leaps from the tree to the ground, charging an Orc who moves to behead Thorin. Small and inexperienced, he still manages to tackle and stab the Orc, buying precious seconds and standing guard over Thorin's body. Smoke and ash swirl around him; against Azog's looming presence he looks almost absurdly small, but he does not flee. His courage, in this instant, is absolute.

The tree gives way under the weight of dwarves and flames. It tilts fully out over the void; the company clings half‑dangling, their feet scrambling against nothing. Orcs laugh and gather burning brands, preparing to finish them. Gandalf, realizing they are moments from death, throws a burning pinecone into the sky and calls out, his voice and the crackling fire sending a signal that eagles recognize. High above, Great Eagles--mighty birds of prey who sometimes ally with the free peoples--swoop down.

The Eagles strike the Wargs, tearing into them with talons, scattering the Orcs. Chaos erupts. One eagle snatches Thorin's limp body; others seize Gandalf, Bilbo, and dwarves from the falling tree as it finally snaps and plunges into the gorge. Orcs plummet with it, their screams cut off in the depths. Azog, thrown back by the assault, manages to regain his Warg and retreats to a higher ledge. He watches, furious but alive, as the Eagles carry his quarry away. Azog survives this confrontation, his vengeance unfulfilled.

The Eagles bear the company north‑west, over rivers and ridges, and set them down at last on a high stone outcrop known as the Carrock. Wind beats around them; the land rolls away in all directions. The dwarves gather around Thorin's still form, fearing the worst. Gandalf bends to him, presses his hand to Thorin's chest, calls his name. After a tense pause, Thorin coughs and slowly opens his eyes. He sees Gandalf first, then Bilbo standing nearby, anxious and ashamed. Memories of his failed charge and Bilbo's unexpected defense flicker across his face.

Thorin, weak but lucid, hauls himself unsteadily to his feet and walks to Bilbo. Earlier in the journey he had told the hobbit, in front of the company, that he had no place among them, that he was a burden. Now, voice rough with contrition, he admits he was wrong. He acknowledges Bilbo's courage, tells him he has never been so wrong about anyone, and calls him a member of the company and a true friend. The other dwarves crowd in, some embracing Bilbo outright, others clapping him on the back. A fellowship, once based on a shaky contract, has become something deeper.

Gandalf and Bilbo walk to the edge of the Carrock. From there, looking east, they can see it at last: the Lonely Mountain, Erebor, far on the horizon, its single peak rising above the lands between. It is still many leagues away; the calendar, though not stated on screen by date, is such that Durin's Day at the end of autumn still lies ahead. But for the first time Bilbo beholds the goal of their quest. The camera lingers on his face as awe and dread mingle in his expression.

He asks quietly, "Is that it?" Gandalf nods. The wind a little stronger now, they stand together, a wizard and a hobbit, staring at the mountain that holds a dragon and a stolen kingdom within.

Far away, inside that mountain, the halls of Erebor lie silent and smothered in wealth. Gold coins form dunes; jeweled cups and plates lie in heaps. The great treasure that drew Smaug decades earlier is still here, undiminished. Beneath it all, buried like some colossal predator in its den, lies the dragon himself. For a moment, everything is still.

Then a single piece of gold shifts, sliding down a scaled flank. The movement grows. The treasure trembles and avalanches down, revealing the ridge of a massive, red‑gold body. At last, an eye is exposed, enormous, slit‑pupiled, and molten in its gaze. Smaug's eye opens. Light glints off the vertical pupil as it narrows and focuses, awake and aware. The presence that destroyed Dale and Erebor, that killed countless dwarves and men by fire and ruin, is alive and waiting.

The story of this first journey, as old Bilbo writes it in his Red Book in Bag End on the day of his 111th birthday, ends here for now: Thorin Oakenshield, Gandalf the Grey, Bilbo Baggins, and their companions stand alive but battered on the Carrock, bound together and looking toward the looming challenge of Erebor and Smaug; Azog the Defiler lives to hunt another day; in Dol Guldur the Necromancer's shadow gathers; and in Bilbo's waistcoat pocket, unknown to his friends, the One Ring--Gollum's lost Precious, Sauron's future weapon--rests quietly, its discovery and concealment the most fateful secret of all.

More Movies Like This

Browse All Movies →

What is the ending?

At the end of "The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey," Bilbo Baggins and the company of dwarves reach the edge of the Misty Mountains after a series of adventures. They encounter a group of goblins, leading to a chaotic escape. Bilbo finds the One Ring during his flight, which grants him the power of invisibility. He uses it to evade capture and ultimately reunites with the dwarves. The film concludes with the group continuing their journey toward the Lonely Mountain, setting the stage for future adventures.

As the film approaches its conclusion, the tension escalates. The company of dwarves, led by Thorin Oakenshield, is navigating the treacherous Misty Mountains. They seek refuge in a cave, but their respite is short-lived as they are ambushed by goblins. The scene is chaotic, filled with the sounds of clashing metal and the frantic shouts of the dwarves as they fight to escape. Bilbo, who has been struggling to find his place among the group, feels a surge of fear and determination as he witnesses the chaos around him.

In the midst of the goblin attack, Bilbo is separated from the dwarves. He stumbles into a dark, damp tunnel where he encounters Gollum, a creature twisted by the power of the One Ring. The atmosphere is tense and eerie, with Gollum's unsettling riddles echoing in the darkness. Bilbo, feeling a mix of fear and curiosity, engages in a game of riddles with Gollum, hoping to find a way out. The stakes are high, and Bilbo's cleverness shines through as he manages to outsmart Gollum, but not without a sense of dread.

During this encounter, Bilbo discovers the One Ring, which he inadvertently finds on the ground. As he slips it onto his finger, he becomes invisible, allowing him to escape Gollum's clutches. The moment is pivotal for Bilbo; he feels a rush of power and fear as he realizes the ring's potential. This newfound ability gives him a sense of confidence, but it also foreshadows the darker implications of the ring's influence.

Reuniting with the dwarves, Bilbo uses his invisibility to help them evade the goblins. The scene is filled with tension as they navigate the dark tunnels, with Bilbo leading the way, feeling a sense of pride and belonging for the first time. The dwarves, initially skeptical of Bilbo's abilities, begin to see him in a new light as he proves his worth.

As they finally escape the goblin tunnels, the group emerges into the light of day, but their relief is short-lived. They are pursued by the goblins and wargs, leading to a frantic chase through the forest. The dwarves, Bilbo, and Gandalf work together to fend off their attackers, showcasing their growing camaraderie and teamwork.

The climax of the film occurs when they take refuge in the trees, where they are surrounded by wargs. Gandalf calls upon the eagles, who swoop down to rescue them, lifting them to safety. This moment symbolizes hope and the power of unity, as the group is saved from certain doom.

As the film draws to a close, the company of dwarves, along with Bilbo, is taken to the safety of the eagles' eyrie. They look out over the vast landscape, with the Lonely Mountain in the distance, a reminder of their quest. Bilbo, now more confident and resolute, reflects on the journey ahead. The film ends with a sense of anticipation, as the group prepares to continue their adventure toward reclaiming their homeland.

In summary, the fates of the main characters at the end of "The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey" are as follows: Bilbo Baggins has transformed from a hesitant hobbit into a more courageous and resourceful member of the company. Thorin Oakenshield remains determined to reclaim his kingdom, while the other dwarves, including Kili, Fili, and Balin, have begun to accept Bilbo as one of their own. Gandalf, the wise wizard, continues to guide them, aware of the greater dangers that lie ahead. The film concludes with the promise of further adventures, setting the stage for the next chapter in their journey.

Is there a post-credit scene?

In "The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey," there is no post-credit scene. The film concludes with a focus on the journey ahead for Bilbo Baggins and the company of dwarves. After the climactic events of their encounter with the trolls and the subsequent arrival at Rivendell, the film wraps up with a sense of anticipation for the adventures to come, but it does not include any additional scenes during or after the credits. The ending emphasizes Bilbo's transformation and the beginning of his unexpected journey, leaving viewers with a sense of wonder about the challenges that lie ahead.

What motivates Bilbo Baggins to join the adventure with the dwarves?

Bilbo Baggins is initially reluctant to join the dwarves on their quest to reclaim the Lonely Mountain and its treasure from the dragon Smaug. However, he is motivated by a sense of adventure that is awakened within him by Gandalf's encouragement and the unexpected visit from the dwarves. As he contemplates the journey, he feels a mix of fear and excitement, ultimately deciding to embrace the unknown and step out of his comfort zone.

How does Thorin Oakenshield's character develop throughout the film?

Thorin Oakenshield begins as a proud and determined leader, driven by his desire to reclaim his homeland and heritage from Smaug. His character is marked by a deep sense of responsibility towards his people and a fierce determination that sometimes borders on arrogance. As the journey progresses, he faces challenges that test his leadership and resolve, particularly in moments of conflict with Bilbo and the other dwarves. His internal struggle with the burden of leadership and the lure of the treasure ultimately leads to moments of vulnerability, showcasing his complexity as a character.

What role does Gandalf play in the journey of the dwarves and Bilbo?

Gandalf the Grey serves as a guiding force throughout the journey, acting as a mentor and protector for Bilbo and the dwarves. He orchestrates the adventure by bringing Bilbo into the fold, believing in the hobbit's potential despite his initial hesitations. Gandalf's wisdom and magical abilities are crucial in navigating the dangers they face, from encounters with trolls to the dark depths of Moria. His presence provides a sense of hope and direction, and he often intervenes at critical moments to ensure the group's safety.

What is the significance of the One Ring that Bilbo finds?

The One Ring that Bilbo discovers in the dark caves of the Misty Mountains is significant for several reasons. It is a powerful artifact that grants invisibility to its wearer, which Bilbo uses to escape from Gollum and later to aid the dwarves. However, the Ring also has a darker significance, as it is tied to the larger narrative of 'The Lord of the Rings' and represents the corrupting influence of power. Bilbo's initial use of the Ring is innocent, but it foreshadows the challenges he will face as he becomes more entwined with its fate.

How do the encounters with the trolls impact the group dynamic?

The encounter with the trolls serves as a pivotal moment for the group dynamic among Bilbo and the dwarves. Initially, the dwarves underestimate Bilbo's abilities, but when he attempts to pickpocket one of the trolls, he inadvertently alerts them, leading to a chaotic confrontation. The trolls capture the dwarves, but Gandalf intervenes, using his magic to turn the trolls to stone. This incident highlights Bilbo's growth and potential as a burglar, earning him respect from the dwarves and solidifying his place within the group. It also sets the tone for the challenges they will face together, emphasizing the importance of teamwork and trust.

Is this family friendly?

"The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey" is generally considered family-friendly, but it does contain some scenes that may be unsettling for younger viewers or sensitive individuals. Here are a few potentially objectionable or upsetting aspects:

-

Violence and Battles: The film features several action sequences, including battles with orcs and trolls. These scenes can be intense, with characters in peril and some graphic depictions of combat.

-

Dark Creatures: The presence of dark creatures, such as goblins and wargs, can be frightening. The goblin king, in particular, has a grotesque appearance and engages in menacing behavior.

-

Tension and Fear: There are moments of suspense, such as when the dwarves are captured by trolls or when they face the threat of the goblins. The atmosphere can be tense, which might be distressing for some children.

-

Emotional Struggles: Characters experience fear, loss, and moments of despair, particularly Bilbo as he grapples with his insecurities and the weight of the adventure ahead.

-

Mild Language: There are instances of mild language and some crude humor that may not be suitable for all audiences.

Overall, while the film is designed for a family audience, parents may want to consider these elements when deciding if it is appropriate for their children.