Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

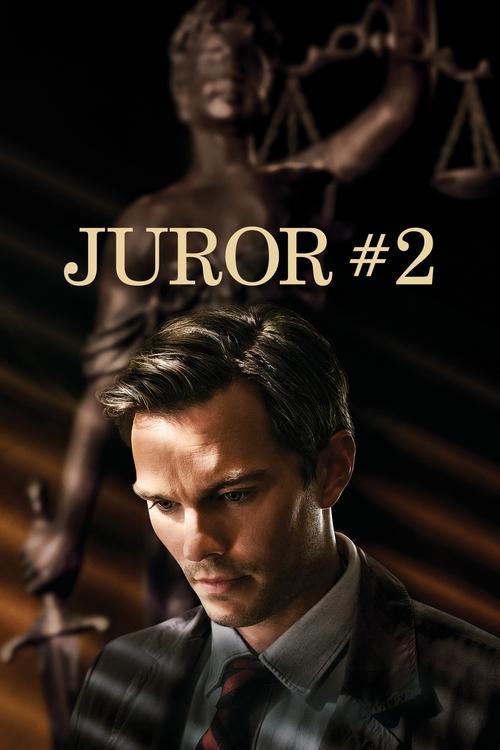

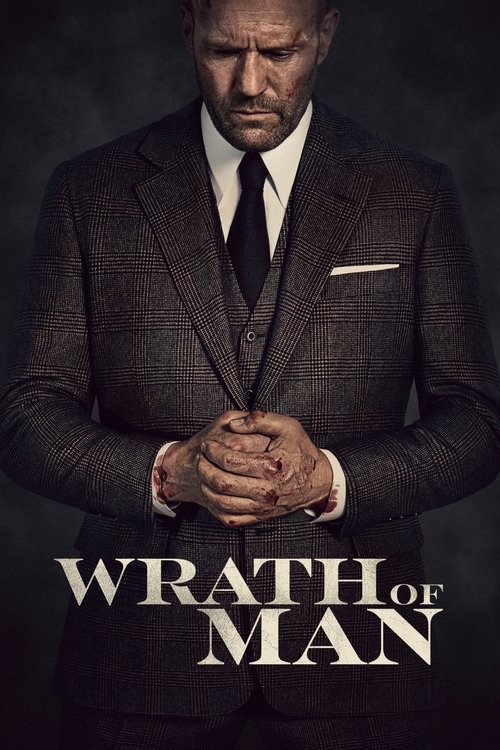

A summons calls Justin Kemp, a journalist and recovering alcoholic, into a courtroom in Savannah, Georgia, where the county convenes a jury for a homicide trial. The victim, Kendall Carter, is introduced to the court posthumously: police discovered her body beneath a bridge on the outskirts of the city. Prosecutor Faith Killebrew lays out a timeline that centers on Kendall's relationship with her boyfriend, James Michael Sythe. The state alleges that a year earlier the couple had a violent confrontation at a nearby bar; on the night of Kendall's death, witnesses place Sythe in a pursuit of Kendall that becomes heated. The autopsy report, entered into evidence, documents blunt-force injuries to Kendall's head and body consistent with severe trauma. An eyewitness tells the jury she saw Sythe at the scene of the body under the bridge. Killebrew frames the case as domestic violence culminating in murder and presses for a conviction.

Justin listens during testimony while private recollections coalesce into a day he has tried to keep buried. During the trial, snippets of time and place flicker through his mind until he remembers, with mounting dread, a moment the night before Kendall's death: driving near the bridge after leaving a bar, he struck something on the side of the road. He has never reported it. The memory intensifies as the prosecution establishes the sequence of events leading to Kendall's body being found. Justin's pulse rises when medical testimony and the estimated time of death intersect with the hour he was on the road.

Afternoon breaks from the courtroom send jurors back to the hotel. Justin seeks out Larry, his Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor, who also practices law in Savannah. Larry listens to Justin's halting account of the impact he believes he caused and the possibility that his car could have been involved in Kendall's death. Larry warns that Justin's prior DUI convictions form a legal hazard: acknowledging hitting someone, even inadvertently, could trigger charges, and his record could be used to demonstrate negligence or recklessness. Larry counsels caution. He explains that if Justin confesses to police or brings the information into open court, the discovery would likely lead to criminal exposure for him and could undercut the jury's impartiality. Larry urges Justin to keep quiet and to think strategically about his responsibilities as a juror and as a potential suspect.

Back in the deliberation room, jurors begin parsing evidence. Eric Resnick, the public defender assigned to Sythe, struggles under a heavy caseload and misses opportunities in his representation. Resnick fails to emphasize critical environmental factors such as poor nighttime visibility on the stretch of road beneath the bridge and neglects to present alternative medical opinions that might cast doubt on the blunt-force-only conclusion of the autopsy. The prosecution's witnesses, rehearsed and methodical, provide observational detail: that Sythe left the bar intoxicated, that the pair argued on the sidewalk, and that an eyewitness later identified Sythe near the scene. For several jurors, these accounts stack into a portrait of an angry man who could have killed Kendall.

Harold, a retired detective seated on the jury, voices doubts about how eyewitness testimony can be shaped by investigators' expectations. He introduces the possibility that confirmation bias may have influenced witnesses and that the police investigation could have been led by tunnel vision. A juror who is a medical student raises another factual point: the pattern of abrasions and fractures on Kendall's body could be consistent with a pedestrian struck by a vehicle and dragged or tossed, not exclusively with a hand-delivered blunt assault. Her observation reframes aspects of the autopsy for the group. These professional perspectives provoke debate; jurors revisit timelines, distances, and visibility.

Justin's secret memory of hitting something festers in the deliberation room. He begins to manipulate conversation, framing arguments in favor of reasonable doubt. At first he speaks on the possibility of rehabilitation and personal change, drawing on his own recovery to suggest that Sythe could be a man who reforms rather than a murderer. He frames sobriety as evidence of capacity for change when he urges other jurors to consider life outside the incident. His words carry the authority of lived experience, and several jurors respond to the notion that Sythe's past does not equal guilt for Kendall's death.

Concurrently, Harold undertakes action beyond the jury's deliberations. Concerned that the investigators could have missed a vehicle collision, Harold searches for vehicle repair records at local body shops and auto garages. He compiles lists of cars that were recently repaired in the nights surrounding Kendall's death. In his investigation he crosses the line of juror conduct by seeking discovery outside the courtroom. Harold narrows the list down to a set of fifteen vehicles whose repairs, timing, or damage patterns warrant further scrutiny. Justin recognizes his own vehicle among those names and registers a spike of panic. Confronted with the possibility that Harold's list could be turned over to the defense or to police, Justin raises objections in the deliberation room and alerts court officials to Harold's extrajudicial actions. A judge, informed of the breach of jury protocol, removes Harold from the panel, citing the integrity of the jury process. Harold disputes the decision but exits the jury after the court's admonition. Justin feels immediate relief; the immediate pressure of Harold's findings recedes.

The prosecution continues to gather material. Faith Killebrew, who harbors ambitions within the district attorney's office, receives information indicating that police officers involved in the initial homicide investigation coached the primary eyewitness on identifying Sythe in a photographic lineup. She confronts detectives and reviews the internal reports. The discovery creates an ethical dilemma for her: if the eyewitness identification was prepped, the reliability of that testimony becomes suspect. Killebrew consults with prosecutors and supervisors but, weighing her responsibility to the case and the political context of securing convictions in a community sensitive to domestic violence, she decides not to seek dismissal. Instead she presses on, augmenting the case with repair records and outreach to forensic specialists who can corroborate the state's timeline.

In the jury room, discussions sharpen into offense and defense. Justin, whose behavior grows erratic under the strain of his secret, alternates between steering jurors toward leniency and, in a shift borne of fear, towards condemnation. When the medical student highlights aspects of the injuries that could fit a vehicle strike, Justin hears the risk of his own involvement become imminent. He reframes his arguments; where he previously emphasized the possibility of rehabilitation, he now emphasizes the eyewitness testimony, the brutality of the injuries, and the trajectory of Sythe's behavior in the bar. He amplifies the testimony that describes Sythe as intoxicated and desperate, suggesting that such a man would be capable of killing Kendall. Other jurors, influenced by Justin's changing tone and his credible recounting of recovery, begin to side with the prosecution's narrative and to weigh the eyewitness identification more heavily than the ambiguities the medical student and Harold raised.

Outside the jury room, Killebrew continues to pursue leads. She orders repair records for vehicles listed by Harold before his removal and compiles those files into a supplemental case notebook. Her staff runs license plate checks and looks for corresponding insurance claims. She does not find conclusive evidence linking any of the repair jobs to a vehicle-to-pedestrian collision that night. Meanwhile, Eric Resnick, pressed for time and resources, misses opportunities to cross-examine certain witnesses aggressively and fails to bring an expert who could dispute the state's reconstruction of the scene under poor visibility conditions. Resnick's omission leaves jurors with the impression that the defense lacks a persuasive alternative explanation for Kendall's injuries.

Justin's marriage becomes entwined with the trial. His wife, Ally, confronts him about his presence at the bar on the night in question after a callous neighbor or acquaintance mentions seeing him there. Ally is pregnant and acutely anxious; she and Justin are still recovering from a prior miscarriage and the prospect of jeopardizing their family's stability terrifies her. During a private, tense conversation, Ally decides to withhold certain facts from Justin about her movements that evening because she fears that truth could escalate legal exposure for them both. She chooses to keep the matter quiet to protect their marriage and their unborn child. Justin accepts the half-truths she offers and returns to deliberations with a private burden that alters his moral calculus.

As the judiciary moves toward verdicts, the jury votes. Under Justin's increasingly forceful influence, the panel votes to convict James Michael Sythe. The deliberation process concludes with guilty verdicts on charges related to Kendall Carter's death. In the courtroom, the court records conviction and sentencing proceedings follow. Sythe stands while a judge pronounces a sentence of life without the possibility of parole. Resnick protests in the hallways at the lack of resources and the errors he believes compromised the defense; Killebrew watches the courtroom formalities and files the win under cases closed.

After the verdict, Justin's internal composure fractures. He confronts Faith Killebrew alone in a hallway outside the courtroom. He accuses her of prioritizing her career and her image as a prosecutor over a thorough and ethically clean investigation, alleging that she sacrificed an innocent man to cement her standing. He tells her that the police primed witnesses and that the repair records and alternative medical opinions were ignored. Killebrew listens to Justin's accusations and, having already known of some internal investigative missteps, maintains that the weight of the evidence and her role in seeking justice for Kendall required moving forward. Justin presses her to reopen the case; Killebrew declines. The two stand in the corridor as Justin makes a last, strained appeal to return justice to the wronged and to spare Sythe from a sentence he cannot survive. Killebrew leaves without reversing the conviction.

Following the trial, Justin takes concrete steps to distance himself from the episode and from his car, which he now sees as implicated in a death. He sells the vehicle that may have struck Kendall. The sale is a physical act of severing a tie and of attempting to manage his interior guilt. Ally, who endured the pregnancy through the public and private strain, gives birth to their child without incident. The child arrives while Sythe remains imprisoned and while official records list Kendall's manner of death as homicide committed by her boyfriend. Life moves forward around the court's finality.

Months after the trial, Faith Killebrew's career ascends; she secures a position as district attorney. Her public profile rises in the community that remembers the Kendall Carter case as a victory for victims of domestic violence. On an unannounced afternoon she appears at Justin and Ally's door. She knocks and exchanges words at the threshold with Justin. The conversation is terse and unresolved; Killebrew stands with the knowledge of decisions she made and the consequences they carried. Justin and Ally watch as Killebrew departs, and the story of grief, conviction, and the private cost of public verdicts ends with lives forever altered: Kendall Carter buried beneath the bridge, James Michael Sythe confined by a life sentence, Justin Kemp living with the memory of an impact he may have caused and the legal finality he helped produce, Ally caring for their newborn, and Faith Killebrew occupying the office whose responsibilities shaped the outcome. The last scene closes on the household as daily life resumes, the courthouse records unchanged and the legal judgment intact.

What is the ending?

Short Summary of the Ending: In "Juror #2," Justin Kemp, a juror in a murder trial, grapples with the possibility that he might have accidentally killed the victim. As the trial progresses, Justin tries to sway the jury towards a not-guilty verdict, fearing an innocent man might be convicted. The movie culminates with Justin's internal conflict and the jury's decision, which determines the fate of the accused, James Sythe.

Expanded Narrative of the Ending:

The ending of "Juror #2" unfolds with Justin Kemp, played by Nicholas Hoult, deeply entrenched in a moral dilemma. As a juror in the trial of James Sythe, accused of murdering his girlfriend Kendall Carter, Justin becomes increasingly convinced that he might have been the one who accidentally killed Kendall. This realization stems from a night when Justin, after almost relapsing at a bar, drove home and hit something he assumed was a deer.

As the trial progresses, prosecutor Faith Killebrew, portrayed by Toni Collette, presents a strong case against Sythe, highlighting his history of violence and eyewitness testimony placing him at the scene. However, Justin's growing unease and guilt lead him to seek advice from his Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor, Larry, who also happens to be a defense attorney. Larry warns Justin that coming forward would likely result in his own prosecution due to his past DUI convictions.

Justin decides to use his own story of recovery to argue for the possibility of change in Sythe, hoping to sway the jury towards a not-guilty verdict. This decision is motivated by his fear that an innocent man might be wrongly convicted. Meanwhile, other jurors, including a retired detective named Harold, played by J.K. Simmons, begin to question the reliability of the eyewitness testimony and the prosecution's case.

As the jury deliberates, tensions rise. Justin's efforts to introduce doubt about Sythe's guilt are met with skepticism by some jurors, who are convinced of Sythe's culpability. The deliberation process is intense, with each juror bringing their own biases and experiences to the table. Justin's emotional state becomes increasingly fragile as he grapples with the weight of his potential involvement in Kendall's death and the moral implications of his actions.

Ultimately, the jury reaches a verdict. The outcome is influenced by Justin's arguments and the jurors' discussions about the reliability of the evidence. The fate of James Sythe hangs in the balance, as does Justin's own future, should his secret be revealed.

The movie concludes with Justin's personal fate still uncertain, as he must live with the consequences of his actions and the verdict of the trial. The ending leaves viewers pondering the moral complexities faced by Justin and the impact of his decisions on those around him. The film's conclusion highlights themes of guilt, redemption, and the complexities of justice, leaving a lasting impression on the audience.

Is there a post-credit scene?

The movie Juror #2 (2024) does not have a post-credit scene. After the film ends, the credits roll with no additional scenes or extras following them.

The film concludes with a significant final moment where Faith, the prosecutor, confronts Justin outside the courthouse about his possible involvement in the victim's death. The movie ends shortly after Faith visits Justin at his home, leaving the resolution open to interpretation, but no further scenes appear after the credits.

What specific event causes Justin Kemp to realize he might be responsible for Kendall Carter's death?

Justin Kemp recalls hitting something with his car on the night of Kendall Carter's death after being at the same bar as Kendall and her boyfriend James Sythe. He initially assumes it was a deer but later fears it might have been Kendall, leading him to realize he might be responsible for her death.

How does Justin Kemp's personal struggle with alcoholism influence his role on the jury?

Justin is a recovering alcoholic with a tenuous hold on his sobriety, which adds to his anxiety and moral dilemma during the trial. His sobriety story becomes a key part of his argument to the jury, as he uses it to demonstrate that James Sythe, the defendant, is capable of change and should be found not guilty.

What role does Faith Killebrew play in the trial, and what are her motivations?

Faith Killebrew is the ambitious prosecutor seeking a high-profile domestic violence conviction to boost her campaign for district attorney. She aggressively pursues the conviction of James Sythe, linking the case to her election campaign and aiming to try the case as many times as needed to secure a win.

Who is Larry, and what advice does he give to Justin regarding his potential involvement in the crime?

Larry is Justin's Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor and a defense attorney. He advises Justin that if he comes forward about possibly causing Kendall's death, he would likely be prosecuted and convicted due to his previous DUI convictions and the jury's likely disbelief in his sobriety.

What are some key mistakes made by the defense attorney Eric Resnick during the trial?

Eric Resnick, the public defender for James Sythe, makes several mistakes including failing to highlight poor nighttime visibility and not presenting an opposing medical opinion, which could have introduced reasonable doubt about Sythe's guilt.

Is this family friendly?

The movie Juror #2 (2024) is rated PG-13 and is generally recommended with extreme caution for older teenagers and adults, not for younger children or sensitive viewers. It is a serious courtroom drama with intense moral and emotional themes rather than explicit content.

Potentially objectionable or upsetting aspects include:

- Moral dilemmas involving justice and guilt, which may be emotionally heavy or unsettling for children or sensitive viewers.

- References to alcohol use and recovery from alcoholism, including scenes with drinking and intoxication.

- Mentions or implications of miscarriage and pregnancy complications, which could be distressing.

- Some tense courtroom and jury deliberation scenes involving accusations, doubts about guilt, and ethical conflicts.

- Minor references to drug use and gang affiliation (tattoos indicating drug-pushing gang membership) and accusations of being stoned.

- A brief mention of street racing and offscreen vomiting.

- The film contains no graphic violence or sensationalized violence, as director Clint Eastwood avoids making violence exciting or cathartic, but the subject matter involves a murder trial and its emotional weight.

Overall, Juror #2 is a thoughtful, intense drama about justice and conscience, suitable for mature teens and adults but not recommended for children or those sensitive to serious ethical and emotional conflicts.