Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

Christmas 1985 approaches in the Irish town of New Ross, and coal merchant Bill Furlong moves through his daily rounds with a heavy, steady gait. He delivers sacks of coal to houses along narrow streets, greets customers, and returns to his own modest home where his wife Eileen waits with their five daughters. Bill carries tools of his trade and the weather on his shoulders; his work keeps his family warm through the winter and provides the rhythm of his days. Between deliveries his thoughts travel backward. In a series of flashbacks he recalls his childhood as the son of a young single mother who endures social exclusion from her own family. He remembers the hard labor allowed to him at Mrs. Wilson's estate, where the wealthy, self-reliant landowner permits the boy to work. Within those recollections Bill sees Ned, a farmhand who lives and works on the estate and whose presence suggests to Bill that Ned is his biological father. These memories come in fragments: small hands hauling coal, furtive glances from neighbors, and the steady, watchful face of Mrs. Wilson supervising the work.

Bill's deliveries bring him regularly to the convent that dominates a portion of town life. He piles coal near its stone walls and exchanges curt salutations with the nuns who run the place. On one of these runs he first notices a thin, frightened teenage girl named Lisa standing at the convent gate. Lisa catches his eye and pleads for help in a low voice; she looks out of place beneath the convent's austere façade. Bill offers what comfort he can in a few brief words and leaves with his cart. The incident registers with him, and in his mind the convent and its occupants become a locus of unease.

Some time passes and Bill adjusts his usual schedule: on one morning he sets out earlier than expected with the coal cart, moving through streets still grey with dawn. He arrives at the convent and, following his routine, opens the coal shed to load coal. Inside, to his shock, he finds another girl locked in the dim, cramped space. The girl is Sarah. She crouches against the cold stone, her breath clouding in the shed's frigid air. She tells Bill in a thin, terrified voice that she has been locked there and that she will have to give birth in that exact place in five months. Her clothing is inadequate for the cold and evidence of mistreatment marks her thin wrists and hollow cheeks. Bill steps back at first, then kneels, speaking softly and trying to gauge whether the girl can be moved without provoking the people who confined her. Sarah's fear clamps her lips closed; she refuses to name anyone who put her in the shed.

Bill carries Sarah from the coal shed through the convent yard and into the presence of the nuns, who adopt a composed, regulated demeanor as they receive him and the girl. The nuns lead Sarah and Bill into the convent's office, a small, comfortably appointed room where Sister Mary, the Mother Superior, conducts administrative business. Sister Mary sits behind a wooden desk, hands clasped; she listens to Bill's halting explanation. Sarah remains near the doorway, withdrawn and untrusting. Under Sister Mary's examination Sarah relents from the truth she had initially told Bill; she speaks now of being locked in the shed while playing hide-and-seek with other girls. Sister Mary accepts this account with a kind of practiced, calm attention, then takes Bill aside to ask questions about his family. She reminds him, with disquieting civility, that both his wife Eileen and his eldest daughter Kathleen attend the school run by the convent. Sister Mary's voice shifts to a tone of implication: if Bill speaks publicly about what he has seen at the convent, serious consequences could follow for his younger daughters' access to that education. The threat hangs in the office as Sister Mary arranges a simple but pointed exercise in social leverage.

Before he leaves, Sister Mary takes out card stock and writes a short Christmas greeting. She slips a sum of money inside the folded card, addresses the envelope to "Eileen," seals it, and hands the sealed envelope to Bill. Her hands move with the measured movements of a person used to controlling the edges of people's lives. Bill accepts the envelope, holding it as if the paper itself were part of the bargain that he now understands takes place whenever he must interact with the convent. He leaves the office with Sarah escorted back to the accommodations the nuns provide. Bill returns home with the sealed envelope tucked into his jacket, but he does not present it to his wife immediately. He walks in the front door as he always does, the ordinary domestic space filling around him, and he moves through the house with an inward agitation. He tells himself he has misplaced the envelope; he stows it in a pocket and keeps the secret to himself.

Eileen learns of the convent's card through her own conversation with Sister Mary, who mentions that she has sent a Christmas greeting to the Furlongs. When Eileen asks Bill about the envelope, he pulls it out and hands it to her as if he has just remembered. She opens it and discovers the cash folded within; she frowns, puzzled, and asks why Bill did not give it to her earlier. Bill deflects her question with a casual explanation that he simply forgot. Eileen's expression reveals more than her words do; the couple exchange a strained look that does not resolve into the ordinary warmth of a family preparing for the holidays.

Bill's predicament grows, and wordless pressures mount in the town. He visits the local pub owned by Mrs. Kehoe, a woman who knows the town and the way its social currents run. Mrs. Kehoe watches Bill and offers blunt advice: he should "toe the line" and not speak against the convent. She explains that the nuns wield social influence that can complicate the livelihoods of anyone who opposes them. Her counsel arrives with the pragmatic weight of someone who has seen neighbors' lives altered by standing up to powerful local institutions. Bill listens, his jaw tightening, aware that his silence and compliance weigh differently against his conscience than against his family's security.

As Christmas nears Bill decides to buy Eileen a present. He walks through town after dark, pausing beneath shop windows where lights display goods for the holiday. In one window he sees a toy--an object he had wanted as a child but never possessed. The sight stirs something tender and long-buried in him. Instead of purchasing the toy, however, he finds his feet taking him back to the convent. He approaches its gate with a resolve that unlaces some of the fear that had earlier governed him. He climbs into the coal shed, opens the door, and finds Sarah there again, present in the same cramped space that she had earlier described as the place where she would give birth. The air inside is cold and foul; Sarah's head is bowed.

Bill speaks to her calmly, addressing her not as an anonymous supplicant but by name, and he tells her that he will not leave her where she sits. He kneels, extends his hand, and slowly wins her trust through small gestures: he offers cloth, he promises warmth, he keeps his gaze steady without judgment. Sarah resists at first; she flinches at voices outside and at any movement that might signal the nuns' return. Bill moves the language of their exchange away from accusation and toward safety. He asks for nothing in return. Step by step he persuades her that she can stand and walk with him. They leave the convent grounds through a side path, passing neighbors and townspeople who look on without intervening. Bill holds Sarah's arm when she stumbles; he carries heavier materials and steadies the younger body when roofs and steps challenge them. At a point where the weight of movement becomes too much for Sarah's weak legs, Bill lifts her into his arms and carries her the remaining distance to his house, his breath visible in the cold air as he crosses the final stretch of road.

Inside the Furlong home Bill arranges a space near the hearth for Sarah. The house smells of coal smoke, bread, and the low, domestic noise of girls playing in the next room. His daughters peek at the new arrival through doorways and around curtains; Kathleen, his eldest, meets Bill's eyes with a mixture of curiosity and concern. Eileen takes Sarah's shoulders in her hands and guides her toward a blanket near the fire. Bill watches his wife move with a mixture of relief and wariness. He sits by the stove and takes off his wet coat, folding it with the care one uses for a person's outer armor. Sarah, warmed and fed from a bowl provided by Eileen, begins to regain color. She remains guarded in conversation, insisting on few things and refusing to elaborate on how she came to be locked in the shed. Bill does not press for details; he focuses instead on immediate needs--warmth, clean clothing, food. He lights the lamps and watches flames tremble across the coal in the stove.

Over the next hours the house settles into a new normal with Sarah present. The Furlong girls give her small gifts they can spare. Kathleen speaks to Sarah in a soft, younger voice that is both protective and inquisitive. Bill, who has carried the weight of his past and the practicalities of business, allows himself to smile toward the girl. The smile is tentative at first, but when Sarah replies with a small, unguarded grin, Bill's face opens with relief. He runs his hands over his coat sleeves and tells a small, simple story from his childhood to ease the tension in the room--an anecdote about wanting a toy he could not have, the same toy he saw in the window earlier. In the presence of his family and this reluctant guest he allows himself to feel the warmth of the hearth as more than physical heat: he feels a protective commitment to the person who will sleep that night under the roof he provides.

No violent confrontations, no deaths, and no public legal battles play out onscreen; instead the film follows the careful, fraught choices Bill makes in deciding to shelter Sarah despite the implied risks. The convent appears in the background as an institutional presence whose social leverage shapes the characters' options: Sister Mary's card and the sealed envelope, the nuns' willingness to offer a surface of care while exerting control, and Mrs. Kehoe's warning about speaking out all structure the terrain in which Bill acts. Bill's interactions with the town--his carts of coal, his business at the pub, the way neighbors pass without intervening as he moves Sarah through the streets--compose a portrait of a man negotiating private compassion against public pressure.

The narrative closes on a domestic note. Bill tucks Sarah into bed near the fire while his wife watches with quiet concern. The family prepares for Christmas with small, ordinary rituals--wrapping small parcels, sweeping the hearth, murmuring prayers or wishes that do not require explanation. Bill stands in the doorway of his house and takes a slow, steadying breath, looking toward the small, sleeping figure who will remain under his roof. He looks toward his daughters, toward Eileen, and for a moment the solidity of his household steadies him.

The film ends with a dedication: the screen displays words honoring the women who were victims of the Magdalene laundries, institutions that operated in Ireland from 1922 to 1998. Those closing words follow the final domestic scene and appear against a dark background after the last images of the Furlong home. Within the narrative itself no character dies, and no scene depicts a killing; the story's conflicts unfold through coercion, social pressure, and the choices characters make about sheltering or silencing the vulnerable rather than through physical violence that ends life. The last shot leaves Bill standing beside his household hearth as the dedication text appears, and the camera holds on the quiet interior of the Furlong home before fading to black.

What is the ending?

Is there a post-credit scene?

What are the main character traits and struggles of the two Zacks in Things Like This?

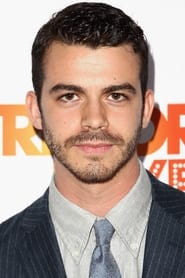

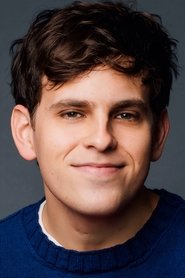

The two main characters, both named Zack, have distinct traits and struggles. Zack #1 (Max Talisman) is a plus-sized hopeful fantasy author with a big personality and self-doubts about his unpublished novel. Zack #2 (Joey Pollari) is an aspiring talent agent stuck as an assistant to an exploitative boss, dealing with anxiety and low self-confidence despite being conventionally attractive. Both struggle with self-worth, which is the main obstacle to their relationship.

How does the film portray the romantic relationship between the two Zacks?

Their romance is depicted as tentative and unlikely, marked by a series of meet-cutes that often go awry due to their insecurities and self-doubts. The relationship is more about their personal struggles with self-worth than just their being gay men, making it a quintessentially queer love story. The film balances witty banter, sentiment, setbacks, and misunderstandings without relying on deception or gimmicks.

What role does the supporting character Ava play in the story?

Ava, played by Jackie Cruz, is a co-worker and supportive friend to Zack #2. She provides comic relief and sharp dramatic moments, often calling out Zack Mandel's self-centeredness and lack of curiosity about others. Although the film reveals she is a lesbian only at the end, her character underscores Zack Mandel's self-absorption and adds depth to the friend group dynamic.

How is New York City depicted in the film?

New York City serves as a vibrant backdrop for the story, with cinematography capturing the city's pulse and energy. The setting complements the lively and chaotic friend group and the unfolding romantic comedy, enhancing the film's authentic and inclusive storytelling vibe.

What are some notable elements of the film's style and tone?

The film embraces rom-com formulas with sharp dialogue, witty banter, and laugh-out-loud moments, such as a chaotic date scene. It balances humor and heart, with an upbeat score and a lively ensemble cast. The tone is sincere and sweet, focusing on themes of finding family and self-acceptance within a queer context.