Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

The film opens on the aftermath of a calculated killing. Vivian Hill, an environmental consultant whose signature is required to greenlight an oil pipeline, is discovered dead after she refuses to falsify an impact report for the project. Investigators determine that her refusal has led to her murder: operatives tied to the pipeline's backers silence her to keep the document falsified and the project moving. Her husband, Stanley Hill, a former special forces operative, learns of his wife's death and, driven by that knowledge, moves with lethal precision. With the aid of his longtime friend Dennis, Stanley begins eliminating the men and women he identifies as responsible for Vivian's killing and for the broader conspiracy to bury the environmental assessment. They methodically target each conspirator connected to the forged report: Stanley and Dennis stalk corporate advisors, contractors, and local officials who signed or benefited from the fake document. The killings are direct and violent; Stanley executes at close range those he deems culpable, firing into cars and offices, while Dennis handles surveillance and logistics. Among their list is Governor John Meserve, the politician who pushes the pipeline through state channels; Stanley confronts Meserve and shoots him dead, ending the governor's life in an abrupt, public assassination intended to punish the man who greenlit the cover-up. As the body count rises around the pipeline scheme, Stanley's campaign of retribution draws law-enforcement attention and triggers a manhunt.

In a different city, Yūsuke Kafuku's life unfolds in patterns that appear ordinary at first. Yūsuke is a stage actor and director who lives in Tokyo with his wife, Oto, a screenwriter. Oto composes the stories she narrates to him after sex; she improvises, then records those narratives onto tapes that Yūsuke listens to as he memorizes lines for productions. He keeps a red Saab 900 Turbo that he often drives alone, and he studies his roles by replaying Oto's voice. After a performance of Waiting for Godot, Oto brings a young television star, Kōji Takatsuki, into their apartment. Yūsuke knows Kōji's face from TV, and their acquaintance is casual at first.

Weeks later, when a theater festival where Yūsuke is scheduled to serve as a judge is postponed, he returns home earlier than expected and discovers Oto in bed with Kōji. He watches the two of them without interrupting, remaining in the doorway and absorbing the scene rather than confronting them. On a separate occasion Yūsuke is involved in a car crash that damages his eyesight; doctors diagnose the beginning of glaucoma in one eye and prescribe medicated drops that he must use regularly to slow the loss of vision. Life continues in a brittle way: Oto's habit of recording stories persists, and those tapes remain part of Yūsuke's rehearsal routine even as the marriage shows fractures.

One day Oto asks Yūsuke to have a serious conversation with her. He declines to sit down with her that day and instead drives away, thinking he can put off the talk. When he returns home in the evening, he finds Oto collapsed on the floor; she dies of a brain hemorrhage. There is no external perpetrator: Oto's death is a sudden medical event discovered by Yūsuke when he enters the apartment. At her funeral Yūsuke grieves publicly but when he performs the title role in Uncle Vanya onstage he breaks down, the accumulated shock of infidelity, guilt and loss collapsing into a visible breakdown during the performance.

Back in the city where the pipeline murders escalate, law enforcement narrows on Stanley. Police surround a location where Stanley is tracked; rather than surrender, Stanley performs an act he expects will draw lethal force. He attempts to engineer a suicide by cop--he lifts a firearm and forces the officers to shoot him. The strategy fails to kill him because he is wearing heavy body armor under his clothing. Bullets puncture the armor but do not penetrate his torso, and he collapses still alive while dozens of officers swarm the scene. He is taken to a hospital to recover, wounded but breathing, his body protected by layers he did not disclose. The arrest or capture is not final: a corrupt cop who had previously escaped detention infiltrates the hospital. The officer confronts Stanley in a recovery ward, the two men exchanging words, and in that moment Stanley draws a pistol his daughter had given him earlier and shoots the corrupt officer dead. He kills the cop at point-blank range in the hospital bed area; medical staff and security react but the corrupt officer is no longer moving when they reach him.

At the hospital, Stanley's daughter learns what the authorities plan to do with her father. Because of Stanley's prior membership in special forces units, the government indicates that he will be processed through a military tribunal rather than a civilian court. That process, she is told, will deny Stanley normal legal protections: there will be no typical trial, no civilian defense counsel, and no avenue for public appeal. The daughter recognizes that the military court's procedures amount to an indefinite detention without the protections of civilian justice. While Stanley recovers and the daughter confronts bureaucratic inevitabilities, Dennis arrives at the hospital and extracts Stanley. Dennis had helped plan the earlier killings and now facilitates Stanley's escape from custody; they leave the facility and flee together. In the wake of the escape, the daughter receives a postcard weeks later: it arrives postmarked from Brazil, where U.S. extradition for the charges facing Stanley is effectively impossible. The card contains a terse message in Stanley's handwriting saying he is safe in Brazil and that he hopes to see her again some day. The daughter reads the postcard alone in her apartment, the thin assurance a poorly substituted closure for everything that has happened.

Meanwhile, Yūsuke accepts an offer two years after Oto's death: a residency in Hiroshima to direct a multilingual production of Uncle Vanya. The festival organizing the event stipulates that, for insurance reasons, he must be chauffered in his own car between accommodations and the theater. He protests, but the festival assigns him a young reserved driver, Misaki Watari. At first Yūsuke resists the arrangement, but over repeated drives they develop a quiet rapport. Misaki is reticent in conversation but she listens closely, and she shares fragments of her life that reveal a history of trauma. She tells Yūsuke she grew up in Hokkaido and, after a landslide destroyed her childhood home and killed her mother, she left her hometown and made a living driving garbage trucks and other vehicles. She bears a scar on her cheek from the landslide; she has not pursued cosmetic repair, and she keeps the mark visible.

Gong Yoon-su, the dramaturge assigned to the Hiroshima production, assembles a cast that performs in several languages and brings unexpected dynamics into rehearsals. Yūsuke becomes impressed by Lee Yoo-na, an actress who does not speak during the production but uses Korean Sign Language for communication; her performance as Sonya is intense and quiet. To Yūsuke's surprise, Kōji Takatsuki auditions and wins the role of Uncle Vanya. Kōji, the younger actor who had been seen with Oto before her death, appears in the rehearsal room with brash charm but also an unmistakable vulnerability.

Outside rehearsals, Kōji confides in Yūsuke about his unreciprocated feelings for Oto. He alternates between defending his behavior and revealing his guilt for participating in an affair with a married woman. At a late-night drinking session Kōji lashes out at a man who photographs him without permission and attacks him in a street altercation. The man collapses during the fight and is seriously injured. Police intervene at rehearsal after the injured man dies from the wounds he sustained in the alley fight; the killing traceably follows Kōji's assault. The authorities arrest Kōji and charge him with the homicide or with assault precipitating death; the production is thrown into turmoil. The festival gives Yūsuke and the theater company two days to decide whether to proceed without Kōji or cancel the entire run. With Kōji detained and the show's future uncertain, Yūsuke must make a choice about the lead role.

Before he makes that decision, Yūsuke asks Misaki to drive him back to her childhood region in Hokkaido. They travel through snow and silent countryside to the place where Misaki's family home once stood. Misaki explains that she was present during the landslide but chose not to attempt to pull her mother from the rubble; she had a scar on her cheek from the event, a wound she left unrepaired as a permanent mark of the night. Standing at the ruins of the home, Yūsuke confesses his own guilt: the conversation Oto wanted to have the day she died had been postponed indefinitely because he chose to drive away, and he now believes that had he been present he might have prevented her death. He tells Misaki about the daughter he and Oto once had, a child they lost years earlier; the daughter's death is a private history he rarely voices. Misaki and Yūsuke embrace at the snowy site, each hugging the other as they face their own acts of omission and loss.

Back in Hiroshima, Yūsuke assumes the role of Vanya himself when the company decides to continue the production without Kōji. He prepares rigorously, using Oto's tapes and his own rehearsal notes. On the night of the opening performance he steps onstage and delivers the role with full intensity. Throughout the play his face is often turned toward the audience, toward Misaki in the front rows, toward the multilingual company he has assembled. Lee Yoo-na, performing as Sonya, speaks her final pages in Korean Sign Language with a performance that cuts through the theater; during the climactic concluding lines she signs and delivers Sonya's closing speech about angels, the sky and the end of earthly suffering. Yūsuke's portrayal of Vanya is raw; he allows the audience to see his grief as a living thing. The crowd is moved, actors exchanging looks of relief and exhaustion after the final curtain.

After the performance, Yūsuke continues to listen to tapes Oto recorded; he discovers, in the deposit of those recordings and in fragments told to him by Kōji, some of Oto's stories that he had never heard in full. Kōji shares with Yūsuke one of Oto's narratives that the two of them had once performed together; the recollection opens a space in which Yūsuke accepts both the infidelity and the intimacy of his late wife's storytelling practice. He acknowledges that Oto conceived those tales after sex as a ritual they performed together, a habit that bonded them against their shared sorrow when their daughter died years before. Yūsuke accepts that he knew--partly--of Oto's affairs, and he allows that her love for him had still been real even as she sought intimacy elsewhere.

Some time after the Hiroshima run, Misaki relocates to South Korea and begins a new life. One day she shops for groceries and then returns to a parking area where Yūsuke's red Saab is parked. The Saab now holds a dog that sleeps curled on the passenger seat. Misaki removes the surgical mask she wears in public, revealing that the scar on her cheek has faded to the point that it is barely noticeable. She closes the Saab's door and begins to drive it away down a Seoul street, the dog visible in the window.

Interwoven with Yūsuke's journey are the consequences of Stanley's campaign of vengeance. After escaping from the hospital with Dennis's help, Stanley and Dennis continue their violent purge of those implicated in Vivian's death. They target men they trace to the fabricated environmental report and to the decision-makers who overrode Vivian's refusal. In daylight and under cover of darkness they assault safe houses, tracking down consultants who forged signatures and executives who paid for the falsified documents. Stanley uses small weapons and handguns, executing some victims at point-blank range in cars and office lobbies; Dennis assists by surveilling and cutting communications for their targets. The pair's actions culminate in the assassination of Governor John Meserve. In a confrontation arranged by Dennis's reconnaissance, Stanley corners Meserve in a suburban estate and shoots him dead at close range; Meserve falls and bleeds out on a manicured lawn, his life ended by a single sequence of gunshots delivered by Stanley.

News of the assassinations and the spate of murders in connection with the pipeline scandal forces a national response. Police attempt to re-arrest Stanley and Dennis; a corrupt officer who had initially escaped and later confronted Stanley at the hospital is shot and killed by Stanley with the weapon his daughter had given him. The corrupt officer dies on the hospital floor from Stanley's gunfire. Dennis helps Stanley disappear after the hospital killing; they cross borders, avoiding extradition. Weeks after their escape, a postcard arrives at Stanley's daughter's address. It is stamped from Brazil. The short message from Stanley affirms that he is alive and living where U.S. law cannot easily compel his return. He expresses hope that he will see his daughter again one day and signs his name. The daughter reads the postcard and holds the thin hope it contains.

Kōji's legal fate follows his arrest for the man's death after their altercation. The police charge Kōji based on the violent fight in which he lashed out at the photographer; the beaten man's subsequent death from the wounds leads to criminal proceedings. Kōji sits in custody while Yūsuke and the theater company decide how to proceed with Uncle Vanya; they choose to continue with Yūsuke as the lead. Yūsuke's final performance as Vanya ends the production's crisis and gives him a public exhalation of grief and discipline. Lee Yoo-na's Sonya delivers her farewell lines in Korean Sign Language; the gesture is precise and final, and it completes the play's staged trajectory from private sorrow to an accepted, communal release.

Misaki's trip to Hokkaido, the confession she makes about leaving her mother in the landslide's wreckage, and her small physical scar form a narrative counterpoint to Stanley's violent retribution and to Yūsuke's private mourning. At the ruined house in the snow she explains she had the chance to rescue her mother and did not take it; the omission that left her mother dead in a collapsed home is the wound she carries. Onstage in Hiroshima, Yūsuke tells the story of his delayed conversation with Oto, explaining to himself that his choice to drive away the day she requested a talk created the conditions for her being alone when the brain hemorrhage took her life. Misaki and Yūsuke stand at their respective ruins--one geological, one marital--and each confronts the choices that allowed loss to happen.

The film's final scenes tie the parallel arcs together by showing the aftermaths of actions taken. Yūsuke remains in contact with the people who worked on the Hiroshima production; he continues to listen to Oto's tapes and to drive the red Saab at times. Misaki, now living in South Korea, drives the Saab away from a market, the dog sleeping inside, her scar nearly invisible, and she removes the mask she had worn in public as routine. Stanley is alive in Brazil; his daughter holds his postcard and reads his simple words in a quiet apartment. The documentary record of the pipeline scandal remains unsettled: officials investigated, murders occurred, and the governor is dead, felled by a man who used his special forces training to mete out vengeance. Oto is dead from a brain hemorrhage found by her husband; the man Kōji attacked dies from the injuries sustained in that assault and Kōji is arrested; Misaki's mother is killed in a landslide after Misaki chooses not to pull her from rubble; Vivian Hill is murdered because she would not falsify an environmental report. The film ends with these loose threads left in different places: Stanley in exile whose daughter receives the single postcard from Brazil, Yūsuke having completed his production and continuing his work while he keeps Oto's tapes, Misaki driving a new life across national borders and the Saab bearing a dog down a city street. The last image holds on the sedan's red paint as it moves away, and the camera lingers on an empty theater seat long enough for the film to close.

More Movies Like This

Browse All Movies →What is the ending?

Short, Simple Ending Narrative

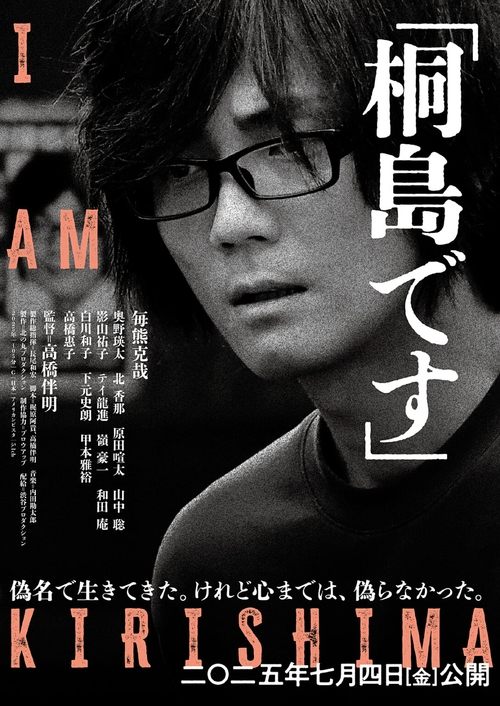

At the end of I Am Kirishima, the main character, who has lived in hiding for decades under a false identity, is ultimately revealed after his death in January 2024, bringing closure to his elusive life as a fugitive.

Expanded Narrative (Chronological and Scene-by-Scene Description)

As the film nears its conclusion, Kirishima, now known by his assumed name, continues his quiet life as a day laborer at a company that provides both work and modest lodging for its employees. The world around him has largely forgotten the revolutionary movement of the 1970s, and the people who once knew him as a wanted terrorist have long moved on. Kirishima--now called "Ucchan"--blends into everyday life, respected by his coworkers for his reliability and quiet nature. He is known for enjoying beer and rock music, but never speaks of his past or reveals his true identity, not even to those closest to him.

The film lingers on scenes of Kirishima's daily routines: waking early, sharing meals with his coworkers, working diligently, and retreating to his small room at night. There is a sense of monotony and isolation, but also a kind of peace. He occasionally overhears news about the world outside, but reacts to none of it. The camera captures his aging face and the subtle expressions of a man who has lived with deep secrets.

Over time, his health declines. The film does not dramatize his death, but rather presents it quietly: one morning, he does not wake up. His colleagues are surprised and saddened; to them, he was just another ordinary, hardworking man. It is only after his death, when authorities investigate his identity, that the truth emerges. News spreads that the quiet laborer was, in fact, Satoshi Kirishima, a notorious fugitive and former member of the East Asia Anti-Japan Front, wanted for decades in connection with a series of bombings targeting corporations associated with Japan's imperialist past.

In the final scenes, the discovery of his true identity causes a media sensation. The public and the authorities are stunned that he had lived undetected for so long. His former comrades have long since been captured or died, and Kirishima's story stands as a reminder of the failed revolutionary movements of his youth. The film closes with images of his former life as a fugitive juxtaposed with his quiet years in hiding, leaving the audience to reflect on the passage of time and the price of living with secrets.

Key Points of the Ending (Shown, Not Told, Through Scenes and Character Moments)

- Kirishima's Normalization: His daily life is depicted in detail, highlighting the contrast between his violent past and the quiet, almost invisible present.

- The Reveal: The discovery of his true identity is not a dramatic chase or confrontation, but a quiet revelation that comes only after death.

- Legacy and Silence: The reactions of those who knew him as "Ucchan" show how successfully he concealed himself, and the shock of the revelation underlines the solitude of his life.

- Themes: The film emphasizes the loneliness of living with secrets, the inevitability of time's passage, and the bittersweet end of a revolutionary who outlived his movement and remained hidden until the very end.

No further commentary or analysis is added here, but the events and character moments described are as detailed and scene-based as possible.

Is there a post-credit scene?

What is the nature of Kirishima's involvement with the East Asia Anti-Japan Armed Front (EAAJAF) and their bombings?

What is the background and motivation of Satoshi Kirishima's involvement in the bombing campaign?

Satoshi Kirishima was a member of the East Asia Anti-Japan Armed Front (EAAJAF), involved in a series of bombings targeting Japanese corporations seen as symbols of imperialism and exploitation, such as Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Kajima corporation. The bombings aimed to attack these institutions symbolically rather than cause unnecessary casualties, reflecting the group's political goals against Japan's imperialistic past.

How does the film portray Kirishima's life as a fugitive?

The film focuses extensively on Kirishima's mundane life while on the run after most of his comrades were arrested. He adopts the alias Hiroshi Uchida and lives quietly for nearly fifty years, working as a day laborer and blending into society, all while hiding his true identity. This duality between his revolutionary past and his hidden present is a central theme, showing his psychosynthesis shaped by isolation and loss.

What personal challenges does Kirishima face throughout the story?

Kirishima experiences personal losses such as his girlfriend breaking up with him due to his political beliefs. He also struggles with loneliness and the psychological impact of seeing his comrades imprisoned or dead. His long concealment under an assumed identity adds to his internal conflict and emotional isolation.

How does the film depict the political and social context of Kirishima's actions?

The film situates Kirishima's story within the broader context of 1970s Japan, marked by political extremism and social upheaval. It shows the violent actions of radical groups, government crackdowns, and the failure of the ultra-leftist movements to achieve their goals. This historical and political backdrop is presented with a sense of nostalgia and social drama, emphasizing the consequences of the era's activism.

Is this family friendly?

"I Am Kirishima" (2025) Family Friendliness:

While there are no explicit descriptions of overt violence or graphic content in the reviews, the movie's themes and genre suggest it may not be suitable for young children or sensitive viewers. Here are some considerations:

- Genre: The film is categorized as a crime drama, which might imply mature themes, including discussions of bombings and societal unrest.

- Content: Although specific objectionable scenes are not detailed, the narrative focuses on a fugitive's life, which could involve tense or disturbing elements.

- Tone: The film explores serious societal issues such as capitalism and nationalism, which may not be appealing or suitable for younger audiences.

Overall, while "I Am Kirishima" doesn't appear to contain explicit material like excessive violence or strong language, its themes and mature subject matter suggest it may not be family-friendly for younger children or overly sensitive viewers.