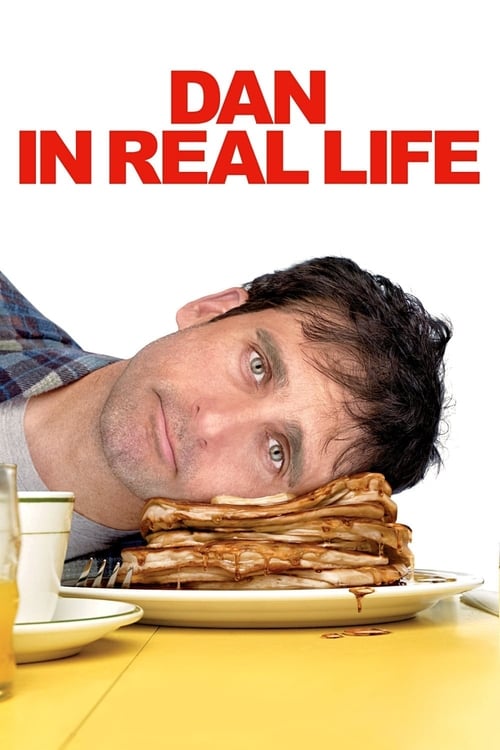

Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

Dan Burns wakes in the dim, gray‑blue of an early autumn morning, in a modest suburban house that still feels too big for one adult and three girls. He lies there for a moment, listening. Somewhere down the hall, pipes rattle, a toilet flushes, a door slams. The house is alive with his daughters, as it has been for the four years since his wife died, but there is still that empty space next to him in the bed, a silent reminder of the life that ended and the life he has been piecing together since.

He forces himself up. In the bathroom mirror he is weary but functional: a man in his early forties, careful, contained. Dan Burns is a newspaper advice columnist, a kind of "agony uncle" whose face runs above a column that tells strangers what to do in matters of life and love. He brushes his teeth, thinking about the next column--maybe something about "honesty in relationships"--and he feels the usual twinge of irony. He dispenses wisdom for a living and yet, in his own life, he mostly just survives.

Downstairs, chaos. Jane Burns, seventeen, tall and sharp and restless, is rattling car keys in one hand, cereal bowl in the other. Cara Burns, fifteen, hair a little wild, eyes already burning with intensity, is on the phone, whisper‑arguing with someone named Marty. Lilly Burns, eight, small and open, pads around in socks, looking for a homework folder and, more than that, still unconsciously looking for a mother who isn't there.

"Okay, everybody, shoes, bags, let's move," Dan calls, defaulting to that brisk, managerial tone that passes for authority.

Jane lifts the keys. "Dad, I'm driving. It's ridiculous. I have my license. I'm driving."

He feels his stomach knot. "You're not driving." It comes out faster, harsher than he means.

"Why not?" she snaps. "You said after my birthday we'd talk about it. It's been two months. I am literally the only person in my class who--"

"Because I said so," he cuts in, then hears himself and winces. "Because… it's raining. Because we've got a long drive. Because I need to--"

"--control everything?" she shoots back. The bowl clinks onto the counter. "You don't trust me with a car, you don't trust me with anything."

Cara hangs up the phone with a sharp, plastic click. "He doesn't trust anyone with anything," she mutters. "Except his readers."

"Hey," Dan says, trying to pivot to humor. "My readers are very trustworthy. Also, they tip well. Now, bags in the car."

Lilly slips her small hand into his as they move toward the door. "Do we have to go right now?" she asks. "I can't find my sweater. Mom always--" She stops, realizing what she's said.

Dan bends down, searching her eyes. "We'll find it," he says gently. "We always do."

By the time they're in the car, the overcast sky has brightened into a washed‑out autumn light. This weekend is the annual family fall reunion at his parents' large, rambling beach house in Rhode Island, a place that--on paper--should mean comfort and restoration. Instead, Dan feels a mix of dread and obligation. So many people. So many opinions. So many ways to be reminded of what he has and what he has lost.

They drive. Jane sulks in the front passenger seat, arms folded, eyes fixed on the road she believes she should be driving. Cara texts furiously, then sighs theatrically, then declares to no one in particular, "Marty and I are in love, actually. Not that anyone in this car cares." Lilly falls asleep with her head tipped against the window, a child still, for a little while longer.

"Three days," Dan says at one point, glancing in the rearview mirror. "You've known this boy three days, Cara."

"Three days is enough when it's real," she fires back instantly. "It's love, Dad. You write about it for a living. You might want to recognize it when it's in your own family."

He opens his mouth, tempted to lecture about teenage infatuation, brain chemistry, impulses. Instead, he hears himself say, "We'll see."

Hours later, the Rhode Island coastline appears, that familiar gray‑blue expanse of water, the wind picking up, trees along the road streaked with orange and red. They pull into the gravel drive of the Burns family house, a vast brown‑shingled place that looks like it's grown out of the rocks and dunes over generations. The air smells of salt and damp earth. Laughter spills from the open front door.

Nana Burns, small but formidable, is there first, arms wide, scooping Lilly up and scolding Jane lovingly for growing so tall. Poppy Burns, apron tied firmly at his waist, stands in the doorway behind her, smelling of onions and garlic, beaming. "There's my boy," he says, clapping Dan on the shoulder. "How's the world of bad decisions and people who need your sage counsel?"

Dan smiles thinly. "Job security, Dad."

Inside, the house is a busy mosaic: siblings and in‑laws and cousins everywhere, kids weaving around adults, someone chopping vegetables in the kitchen, someone else setting up folding chairs in the big living room. The air hums with overlapping conversations and the kind of affectionate teasing that can turn, in an instant, into something sharper.

Almost immediately, Dan is pulled into the current--helping with luggage, fielding questions about his column, dodging remarks about his love life. Poppy corners him by the sink, dish towel in hand.

"You know," Poppy says, "four years is a long time. Your mother and I were talking."

"Uh‑oh," Dan says. "That's never good."

Poppy ignores the joke. "You've done a hell of a job with those girls. But you're still young. You should be… looking. Open to possibilities."

Dan feels that old, familiar tightening. "I'm… functional," he says. "I'm good. The girls are… okay. That's enough."

"Functional isn't living, Danny," Poppy says softly. "You write about living. Maybe you should try some of it."

Later, after lunch and a round of forced‑fun family games, Nana presses the car keys into Dan's hand. "You need some air," she declares. "Go into town. Browse. Don't come back until you've had some actual alone time and maybe spoken to a human being who isn't related to you."

"I have three columns due," Dan protests weakly.

"Then go find some real life to write about," she says, and that's that.

He drives into town under a sky that's shifted to a softer, late‑afternoon gold. The main street is quaint, New England small‑town: clapboard storefronts, a café with fogged windows, a laundromat, a hardware store. He parks in front of a narrow shop with a hand‑painted sign: "Books & Tackle." Inside, the bell over the door gives a tired jingle as he steps into a space that smells of paper and oil and sea salt.

Books line one wall; fishing gear, lures and rods and tackle boxes, line the opposite. It's quiet except for the faint murmur of a radio in the back and the soft rustle of pages. And there, in the aisle between self‑help and literature, stands a woman.

She is browsing, a stack of books in one arm, dark hair pulled back in a loose knot. She is somewhere near his age, in a simple coat and scarf, no visible armor, no performative hustle. Her name--he will soon find out--is Marie.

She looks up as he passes and offers the small, polite smile strangers exchange in bookshops. He nods, intending to glide by, to lose himself in someone else's advice for a change. But he stalls by the self‑help shelf, fingers running along spines labeled with titles not unlike his column.

"Looking for answers?" she asks lightly, her voice low, French‑tinged.

He startles, laughs once. "I, uh… supposedly provide them. Professionally."

Her brows lift. "You're a therapist?"

"Worse," he says. "I'm a newspaper advice columnist. Dan Burns. 'Dan in Real Life.'"

She considers this. "So you tell people what to do. About love. About… all this." She gestures vaguely around them, as if the entire messy human condition is contained on these shelves.

"That's the idea," he says. "They write in with their disasters, I… respond." He shrugs. "It pays the mortgage."

"Do you follow your own advice?" she asks, not teasing, just curious.

He opens his mouth to rattle off a glib answer, something about cobblers' children and shoes, but stops. There is something in the way she looks at him--steady, open--that invites honesty.

"Sometimes," he says slowly. "Less often than I should."

She smiles, a little sadly. "Good. I would not trust anyone who had it all worked out."

Somehow, that opens a door. They drift side by side through the aisles, talking. At first it's superficial--favorite authors, the absurdity of tightly written dust‑jacket blurbs, bad cover art. Then, without quite realizing when or how, they are sitting on a bench by the front window with coffee the owner has pressed into their hands, and the conversation has deepened. He hears himself talking about his daughters, about Jane's fury at wanting to drive, about Cara's "three‑day love," about Lilly's small, heartbreaking slips of memory that still assume a mother will appear in the doorway.

He tells her, for the first time in a long time, about his wife's death four years ago--without euphemism, without deflection. He doesn't describe the cause--he never does, it's too raw, too irrelevant to the daily grind of continuing--but he speaks of the after: the numbness, the nights of moving from room to room in the house because staying still hurt too much, the way he slowly built routines to keep everything from spinning apart.

Marie listens. Really listens. Not like a reader who expects a pithy takeaway, not like a relative who already has a story about him in mind. She asks small, precise questions, nods, laughs in the right places, falls quiet in others. She offers, in return, pieces of herself: that she has been in "a lot of almosts," relationships that made sense on paper but never fully clicked; that she has just moved to the area; that she has, very recently, started something "new" with someone.

Time dissolves. Outside, the light shifts, the street grows darker. Inside, it feels as if the rest of the world has receded and there is only this bench, these two people, this impossible sense that they have known each other longer than this stolen hour.

At some point, her phone vibrates. She glances down, makes a face. "I am supposed to meet someone," she says reluctantly, standing. "A… new relationship. We will see."

He nods, throat tight. "Yeah. Sure. Of course."

She gathers her books, pauses. "Thank you," she says. "For… talking like that. You did not give me advice. That was nice."

He laughs softly. "I can remedy that if you like."

"Don't," she says. "Just… stay honest."

She starts toward the door, then stops, turning back. There is a moment where he can see her weigh something invisible.

"Can I… have your number?" he blurts, surprising himself. "Just… if you ever want to… talk about books. Or hypocrisy. Or… anything."

She smiles, but there's a hesitation. "I have just started this thing," she says carefully. "This relationship. It would not be… appropriate. I don't want to become one of your letters."

He backs off instantly. "No, of course, I'm sorry. That was--"

She studies him, then exhales. "But… you are different. Here." She takes the small notepad he's been using to jot column ideas, pulls a pen from her bag, and writes a number. "I should not give this to you," she says, handing it over. "I just did. See? Already bad decisions."

He takes the paper like it's fragile. "I won't… I mean, I'll… I'll be careful."

"Don't call," she says, and there is both plea and challenge in it. "Unless… you really have something to say."

He watches her leave, the bell chiming softly. For a few seconds he just stands there, the number burning in his pocket, the echo of her voice in his head. Then he remembers his mother's directive and the fact that he has, miraculously, obeyed it.

Driving back, he is not the careful, hyper‑attentive driver he usually is. He is replaying every line, every smile, every moment of surprised recognition. At an intersection he barely registers the red octagonal sign until a siren yelps and blue lights flare in his rearview mirror.

He pulls over, mortified. The cop, a stocky local with a tired patience, approaches.

"Sir, you blew right through that stop sign," the officer says.

"I--yeah, I'm sorry, I was just…" Dan trails off. How to explain that he was running a replay of what felt like his first taste of intimacy in four years?

"Thinking about something more important than traffic laws?" the cop supplies dryly, already writing the ticket.

"Something like that," Dan admits.

Back at the beach house, the windows glow warm against the darkening sky. Inside, dinner prep has morphed into dinner itself. Voices overlap in the dining room, children shout, silverware clinks. Dan steps into the warmth with the aftertaste of coffee and confession still lingering, his heart oddly buoyant.

They pounce immediately. "You look different," Nana observes, eyes narrowing shrewdly. "Did you meet someone?"

He hesitates. He sees Marie's face in his mind, hears her "Don't call. Unless…" and feels his father's words about living. "I… might have," he says.

The room goes still for half a heartbeat, then erupts in delighted noise.

"What's her name?"

"Where'd you meet?"

"Is she sane?"

He flushes. "It's nothing. It was just… a conversation. In a bookstore."

"Go for it," Poppy says firmly, as if this is a football game and Dan has the ball. "Life is short, Danny. Four years is long enough in solitary."

He half‑laughs, half‑deflects. "It's complicated."

"When is it not?" Nana says. "You owe it to those girls to show them what real love looks like again."

Before he can reply, there's another knock at the door, and a gust of cold air blows through as his younger brother Mitch strides in, duffel bag over his shoulder, grin wide. Mitch Burns is the charismatic one, the easy one, the guy who can walk into any room and find the joke.

"Ladies and germs," Mitch announces, "your favorite brother has arrived. And I brought someone."

Dan feels an inexplicable prickle at the base of his neck.

Mitch steps aside, and a woman follows him into the house, shrugging off her coat, cheeks pink from the chill.

It's Marie.

The world tilts. For a second Dan literally cannot breathe. Marie's eyes meet his, register shock, then recognition, then alarm. The entire room, oblivious, hums around them.

"Everyone, this is Marie," Mitch says proudly, arm around her shoulders. "My new girlfriend."

The word lands like a punch: girlfriend.

"Hi," Marie says, and her voice is a little higher than it was in the bookstore, thin with strain. "It is… nice to meet you."

The family surges forward, greeting, hugging, appraising. Dan stands frozen, holding his ticket and the scrap of paper with her number in his pocket like contraband. When she reaches him in the cluster, there's an absurd moment where they both perform the ritual.

"Hi, I'm Dan," he says, as if he didn't spend an hour telling her the tenderest parts of his life.

"Yes, we… have… just met," she says stiffly. "I am Marie."

For a flicker of a second, their eyes lock, and in that look there is an entire conversation: How is this possible? What do we do? Then the family eddies around them again and the moment is gone.

Later, in a corner of the bustling living room, they manage to carve out a tiny pocket of privacy.

"This is… your brother?" she whispers, eyes wide.

"Yes," he says, equally stunned. "I had no idea. He didn't… he'd never… talked about you."

"We met… recently," she says. "I was supposed to meet him after I left the bookstore." She shakes her head, almost laughing at the absurdity. "Of course you're brothers."

"So," he says, heart pounding, "what do we… I mean, we can't…"

"We tell no one," she says immediately. "It would… hurt him. And your family. And my--" She stops. "We had a conversation. That is all. It is not a crime."

"No," he agrees. "Not yet."

They step back into their assigned roles: she as Mitch's new girlfriend, charming his parents, bonding with his nieces; he as the slightly harried widower brother, trying to vanish into the background. Except he can't. Every time he looks up, there she is--laughing with Jane in the kitchen, listening to Cara talk about Marty with surprising seriousness, helping Lilly with a puzzle on the floor. His girls glow around her, instinctively drawn to the warmth and steadiness he recognized in the bookstore.

That night, in the cramped guest room, Jane confronts him.

"Who is she?" Jane demands in a harsh whisper while the house murmurs around them. "You said you met someone. Then Uncle Mitch walks in and it's like… her. That woman. Marie. You've been watching her all night, Dad. It's creepy."

He stares at his daughter, caught. "I met her in town," he says carefully. "Before I knew she was with Mitch. We talked. That's… all."

"Is there anything you're not embarrassing at?" Jane asks, but there is something like worry beneath the sarcasm. "You're flirting with your brother's girlfriend. Just… don't."

The next day begins with thick coffee, bagels, and the low‑level noise of a big family functioning. Activities spill across the hours: walks along the rocky beach in bundled‑up coats, kids building driftwood forts, adults attempting to coordinate schedules for future holidays. Underneath it all, a constant, low electrical current of tension runs between Dan and Marie.

He tries to avoid her, but the house is a maze of near‑misses and shared spaces. In the kitchen, their hands brush reaching for the same mug. In the hallway, they squeeze by each other, shoulders grazing. Each contact is minor, accidental, yet charged.

In the living room, surrounded by cousins and siblings, Dan and Marie find themselves drawn into the same group conversation. Someone jokes about online dating. Poppy ribs Dan again about being "back in the game." Mitch squeezes Marie's shoulder, saying, "Some of us just get lucky." Dan feels his stomach twist.

On the lawn that afternoon, the traditional family football game kicks off. The air has that crisp bite that promises winter is coming; the grass is damp. Teams form loosely, sides chosen with good‑natured bickering. Mitch, naturally, is at the center of things, quarterback for his side. Marie ends up on Dan's team, and the proximity is an exquisite torture.

They huddle. Dan tries to focus on plays, but his attention keeps snagging on the way Marie's hair escapes her hat, the way she laughs when someone suggests a ridiculous trick play.

During one chaotic down, they end up running side by side, jostling, shouting. Dan tosses her the ball, their eyes meeting in an unguarded flash of joy. He feels, fiercely, how easy it would be to slide into this--to laugh with her, to touch her, to pretend the complication doesn't exist.

Distracted, he looks back at her instead of ahead, and the football--thrown hard by an over‑enthusiastic cousin--smashes directly into his nose. Pain explodes across his face, white and hot. He staggers, drops to his knees.

"Dad!" Jane yells, sprinting toward him.

People crowd around, concerned voices blurring. Someone presses a cold cloth to his face. Through the throbbing, he hears Marie's voice, tight with worry, asking if he's okay. He nods, eyes watering. The absurdity that the universe has chosen to literally smack him in the face for his inattention is not lost on him.

Later, as he sits on the porch steps with a bag of frozen peas pressed to his nose, Jane comes to stand over him.

"Stop it," she says quietly.

"Stop what?" he mumbles.

"Whatever this is." She gestures vaguely back toward the house. "The… staring. The… you almost broke your face because you were flirting with Marie instead of paying attention. She's Uncle Mitch's girlfriend. You can't do this, Dad."

He swallows. "I know," he says. "I know."

"Do you?" she asks. "Because meanwhile, you're all over me about driving, and Cara about Marty, and Lilly about everything, and you're the one acting like a--"

"Jane." He cuts her off gently. "You're right. You're right. I'm… confused."

She softens, just a little. "Maybe take some of your own advice," she says, and walks back inside.

That evening, the family crowds into the big living room for the annual talent show. Kids recite poems, a cousin juggles, someone does a magic trick that mostly involves dropping things. Then Mitch steps up with a guitar, grinning.

"All right," he says. "This is for Marie." He glances at her, and she blushes, shifting in her seat. "Dan, come on. You can play better than I can. At least back me up."

Reluctantly, Dan takes a second guitar. His fingers remember the chords whether he wants them to or not. Mitch starts to sing "Let My Love Open the Door," his voice surprisingly earnest. The family claps along, some of the teenagers groaning at the cheesiness. During the bridge, Mitch drops out, nudging Dan.

"Come on, man," Mitch says. "You take it."

Dan looks up. Marie is across the room, sitting on the floor between his daughters. Her eyes are on him, wide, questioning. He swallows and sings the bridge directly to her, the lyrics--about letting love in, about opening a heart that's been closed--hanging between them like a secret. No one else in the room seems to notice the undercurrent; to them, it's just another family bit.

Afterward, when the room has dissolved into chatter again, Marie finds him near the fireplace. Her eyes are bright with unshed tears.

"I have been reading your columns," she says quietly, holding up a worn copy of the paper she's found in the house. "All weekend. About honesty. About boundaries. About not confusing your children by… making promises you cannot keep." Her voice trembles. "And then you sing like that. To me. In front of them. What are you doing?"

"I don't know," he admits, chest tight. "I met you, and I--"

"Since I met you," she cuts in, breath hitching, "I have realized… I do not feel what I should feel for Mitch. It is… friendship. Affection. But not…" She searches for the word. "Not what I feel when I look at you."

He goes very still. The room continues around them, oblivious.

"I cannot keep pretending," she whispers. "I cannot keep lying to him. And I cannot… be this… with you. Not here. Not like this."

"Marie--"

"Tomorrow," she says, wiping at her eyes. "I will talk to him. I will not stay in something false. But you--" She looks at him, almost accusing. "You have daughters watching you. You have a brother who is… in love with me. You write about integrity. You cannot have everything."

She leaves him there, by the fireplace, guitar still in his hands, his own words from years of columns echoing back at him as if someone else wrote them.

The next morning, the house is quieter. There is a strange, tensile quality to the air, as if everyone is unconsciously bracing for something. Over breakfast, Mitch seems more subdued, glancing at Marie with a slightly puzzled frown. She, in turn, is gentle, distant. After the dishes are cleared, Dan realizes suddenly that she has disappeared. Moments later, he hears a door close, sees through the window Marie walking toward her car with a small overnight bag.

He steps outside, heart in his throat. "Marie," he calls.

She turns. Her eyes are swollen; she looks like she hasn't slept.

"I broke up with Mitch," she says simply. "I told him I could not… continue. That it would not be fair." She swallows. "He is hurt. But he will be okay. Your family… they will be okay."

He searches her face. "What about you?"

She looks away, toward the gray line of the horizon. "I need to leave," she says. "I need to… not be in the middle of your life while you decide what you are doing with it." She hesitates. "Goodbye, Dan."

She drives off. He stands there, numb, watching the car shrink and then disappear.

Inside, Mitch is in the kitchen, staring blankly at a mug of coffee. He looks up as Dan enters, eyes red but dry.

"She left," Mitch says. The words land heavy.

"I… I'm sorry," Dan says, the uselessness of the phrase glaring even to him.

Mitch shrugs, a jerky motion. "She said it wasn't… right. That she… didn't feel the way she should." He forces a laugh. "Guess I'm just not her guy."

Dan opens his mouth, wanting to confess everything--that he met her first, that they connected instantly, that every moment of the weekend has been a tightrope. But he sees his brother's raw face and the hungry eyes of his daughters peering from the doorway, and something in him falters. He says nothing.

The day drifts forward in a kind of limbo. The girls sense that something has shifted, but no one supplies details. Then, in the early afternoon, as Dan stands on the porch pretending to read, his phone rings. Unknown number.

He answers. "Hello?"

"Dan." Marie's voice, soft, in his ear. He steps away from the open door, heart thudding.

"Marie. Are you okay?"

"I am still in town," she says. "I checked into a motel. I… could not just drive away. Not yet." There is a pause. "Do you want to meet? To talk. About… what now."

"Yes," he says without hesitation. "Absolutely. Where?"

She suggests the bowling alley in town. Neutral territory, public, absurdly ordinary. They set a time. When he hangs up, he feels both exhilarated and ashamed, twin currents pulling in opposite directions.

He grabs his keys. Jane appears in the hall, blocking his path.

"Where are you going?" she asks.

"Into town," he says. "I… have to see someone."

"Is it her?" Jane presses. "Is it Marie?"

He hesitates, then nods, choosing, for once, not to lie. "I need to talk to her. To figure some things out."

She stares at him, hurt and anger flickering across her face. "You're unbelievable," she says. "Just don't destroy everything, okay?"

On the drive into town, his mind is a churn of possibilities, apologies, half‑formed plans. He reaches the same stop sign he blew through before, the one he got ticketed for. Lost in thought, he rolls through it again without fully stopping. The same cop, as if conjured, pulls him over a second time.

"You again," the officer says, equal parts exasperated and amused. "Didn't we just have this conversation?"

Dan can't even muster an excuse. "I'm… really sorry," he says. "I'm… distracted."

"That much is obvious," the cop replies, writing another ticket. "You keep this up, you're going to lose more than just money."

Ticket in hand, he continues to the bowling alley, a low‑slung building with a buzzing neon sign. Inside, it's dim and rainbow‑lit from the lanes, the air smelling of rented shoes and fryer oil. Families and teenagers occupy some of the lanes; the music is low and dated. It feels, strangely, like neutral ground--no family pictures, no history.

Marie sits at a small table near the ball racks, hands wrapped around a plastic cup of soda. She looks up when he enters, and in her face is a complex blend of relief, fear, and longing.

"You came," she says.

"Of course," he replies, sliding into the seat opposite her.

They talk. At first, it's stilted--logistics, the practical aftermath of her breakup with Mitch. She tells him she was honest, that she did not mention Dan specifically but admitted her heart was elsewhere. He tells her, haltingly, about his conflicting obligations: to his daughters, to his brother, to his own long‑frozen heart that is suddenly, terrifyingly awake.

Gradually, the conversation loosens. They rent shoes. They bowl. The simple, physical act of rolling a ball down a lane, of laughing when they gutter or whoop softly when they manage a spare, cuts through some of the tension. Between frames, they drift closer on the plastic bench, shoulders touching.

"I feel like a teenager," he says at one point, incredulous. "Sneaking around. Lying. Except… teenagers are supposed to be stupid. I'm supposed to know better."

"You do know better," she says softly. "You just… don't know how to be happy yet."

He looks at her. She is so close now that he can see tiny lines at the corners of her eyes, evidence of a life lived paying attention. The noise of the bowling alley recedes. He leans in. So does she.

The kiss, when it happens, is not tentative. It is hungry and urgent and filled with all the things they have been holding back all weekend. For a few seconds, the world narrows to the warm pressure of her mouth, the taste of soda and salt, the feel of her fingers curling in his shirt.

"Dad?"

The word detonates behind him. He breaks away, spinning. Standing at the edge of the seating area are his daughters, faces stunned. Behind them, a cluster of Burns relatives. And behind them, like the punchline to a very bad joke, the two neatly dressed representatives who have come to discuss a potential syndication or expansion of his column.

The entire extended family, plus his potential employers, has arrived at the bowling alley for an afternoon outing and has caught him kissing his brother's ex‑girlfriend.

"Uncle Dan?" a younger cousin says. "What's going on?"

Mitch pushes through the small crowd, expression shifting from confusion to horror as he takes in the tableau: his brother, his recent ex, their linked bodies. The room seems to contract around Dan.

"Mitch, I--" Dan starts.

"What the hell, Dan?" Mitch demands, voice cutting through the general murmur. "You met her yesterday. While she was with me. And then you… what, you sneak around behind my back?"

"Mitch, please," Marie says, stepping forward, eyes shining. "I ended it with you before I--"

"With him," Mitch says, stabbing a finger at Dan, "you don't see a problem?"

Family members shift, some gasping, some whispering. His daughters look stricken; Jane's expression is a mix of "I told you so" and wounded betrayal. The reps glance at each other, clearly wondering what sort of circus they've walked into.

"Marie was the woman I met at the bookstore," Dan blurts, as if that context somehow redeems him. "We… connected before I knew. Before you brought her home."

"So that makes it okay?" Mitch snaps. Without warning, he steps forward and punches Dan square in the face.

Pain flares again at his nose; the world swims for a second. Marie gasps. Someone shouts Mitch's name. The bowling alley falls into a shocked hush around the epicenter of this family implosion.

Marie backs away, eyes wide and wet. "I'm… I'm so sorry," she says, voice breaking. Then she turns and bolts toward the exit, one hand over her mouth.

"Marie!" Dan calls, stumbling after her. His daughters watch, frozen. He swerves around a trash can, pushes through the doors into the parking lot, spots her car pulling out. In a frantic, panicked move, he jumps into his own car, throws it into reverse, looks only at the shrinking shape of her taillights.

He slams backward directly into another car.

A siren whoops. He turns to see, impossibly, the same cop climbing out of the squad car he has just backed into, his face a mixture of disbelief and exhausted irritation.

"Sir," the cop says, walking up to the driver's side window. "I don't know what's going on with you, but you are a menace today."

Dan's hands are shaking on the steering wheel. "I-- I'm sorry. I didn't see--"

"No, you didn't," the cop says. "You ran the same stop sign twice, now you've backed into a police vehicle. I'm going to have to cite you and recommend revoking your license."

It's as if someone has thrown a bucket of cold water over him. The car, the tickets, the accident--these are tangible consequences, the physical manifestation of how completely he has been driving his life on impulse this weekend.

Back inside the bowling alley, after the paperwork and apologies and the slow, humiliating walk back past his watching family, the air is thick with disappointment and confusion. The representatives, murmuring about "timing" and "liability," prepare to leave. His daughters stand apart, a small, stricken cluster.

He could deflect. He could minimize. Instead, something in him gives way. Standing in the garishly lit entryway, rental shoes squeaking on the tiles, he finds his voice.

"I have been an idiot," he says, louder than he intended. Heads turn toward him. "To all of you. To my kids. To Mitch. To… myself."

Silence settles, curious, hesitant.

"I write a column telling people how to live," he continues, words tumbling now. "I tell them to be honest, to put their families first, to not confuse their kids with mixed messages and half truths. And this weekend, I have done exactly the opposite of my own advice." He looks at his daughters, his eyes wet. "I got so wrapped up in how I felt--about someone--that I stopped paying attention to how you felt. To what you needed from me. And I'm… I'm sorry. Deeply, profoundly sorry."

Jane's jaw tightens; Cara blinks furiously; Lilly clutches her sister's hand.

He looks at Mitch. "You're my brother," he says. "I should have told you from the moment I realized who she was. I should have stepped back. I didn't. That's on me. You didn't deserve to find out like this. You didn't deserve any of it."

Mitch, nursing his punching hand, stares at him for a long beat. His face is flushed, his eyes bright. "No," he says finally. "I didn't."

The reps clear their throats. One of them says something vague about "appreciating the candor" and "needing to reassess." Dan barely hears them. His focus is on his daughters.

"I have been so busy trying to keep you safe," he says to them, "from cars, from boys, from the world, that I haven't always seen you. Really seen you. Jane, you're ready to drive. Cara, you… might actually know something about love, even if it scares me. Lilly, you need… more than I've been giving. You needed a mom and got a man hiding behind a column."

Lilly steps forward, eyes huge. "You're not hiding now," she says simply.

He kneels, and she throws her arms around his neck. Jane hesitates, then steps into the hug. Cara joins a moment later, sobbing once into his shoulder. For a fragile moment, the four of them form a small island in the neon‑washed chaos.

The family slowly regroups back at the beach house. The rest of the reunion weekend is quieter, subdued. There are conversations in corners, apologies, some tears, some dark humor. Poppy and Nana are disappointed but proud in a way--they have always believed in confession and consequence. Mitch keeps his distance from Dan, walls up, but he doesn't leave. The girls watch their father with a new, wary attentiveness.

There are no deaths, no car chases, no villains to vanquish--only the slow, awkward work of a family recalibrating around newly exposed truths. The only death that hangs over all of it is still the one that happened four years before, the loss of Dan's wife, unnamed in any of their casual talk because names can cut too sharply. Her absence is the silent third party in every scene, the reason his heart was frozen, the backdrop to his terrified, clumsy attempt to feel again.

Time jumps. The film doesn't stamp a date on the screen; there are no calendar pages flipping, no on‑screen clocks ticking forward. It is simply "later." The leaves have likely cycled through winter and back to green. The Burns family has done what it does best: laughed, fought, played, and, eventually, forgiven.

We are at a wedding. The specifics of the location are not spelled out--perhaps a church, perhaps a light‑filled hall, perhaps even the same Rhode Island beach house dressed up for celebration--but it is clearly a formal event. People are dressed in suits and dresses; there are flowers, music, the low hum of guests settling before the ceremony.

At the front stands Dan Burns, in a well‑fitting suit, looking healthier, looser around the eyes. Beside him stands Marie, in a simple, elegant wedding dress that suits her: nothing ostentatious, just clean lines and quiet grace. Their hands are clasped. They look at each other with the gaze of people who have gone through embarrassment, conflict, and waiting, and have chosen, deliberately, to walk through the fire instead of around it.

In the audience, Jane, Cara, and Lilly sit together in bridesmaid dresses, older by months or a year, their faces open, content. The battles over driving and boyfriends and curfews haven't vanished, but there is a new layer of understanding between them and their father. They have seen him fail spectacularly and own it. They have watched him model, finally, the thing he writes about: vulnerability, responsibility, trying again.

A few rows back sits Mitch. Next to him is Ruthie "Pig Face" Draper--no longer the awkward, teased girl from childhood but a beautiful, confident plastic surgeon whose transformation is both literal and metaphorical. She had shown up at the reunion as a proposed blind date for Dan at one point, a source of both humor and jealousy, but time has shuffled the cards. Now, she is Mitch's partner, laughing at something he whispers, her hand resting comfortably on his. There are no visible hard feelings in his posture, no simmering resentment. The fact that he can sit here, at his brother's wedding to the woman he once dated, with his own new love by his side, is the clearest evidence that forgiveness has taken root.

The officiant speaks words about second chances, about love after loss, about choosing each other every day. Dan and Marie exchange vows, specific lines not echoed from earlier dialogue but infused with what we know: her promise not to settle for "almosts" anymore, his promise not to hide behind columns and control. They mention the daughters, the family arrayed around them, the brother who lost and regained a different kind of bond.

"Let my love open the door," someone jokes quietly as the ceremony nears its end, a nod to the song that once served as a covert confession. This time, there is nothing covert about it. When music swells at the reception--maybe that song, maybe another--it is simply a celebration, not a secret signal.

Dan looks out at the crowd at one point during the reception: his parents dancing slowly in a corner, his girls giggling with cousins, Mitch spinning Ruthie with mock‑graceful clumsiness. Marie's hand slides into his; he squeezes it.

"I never wrote about this," he says softly to her. "Not like this."

"You will," she replies. "But maybe… you don't have to know all the answers first."

He laughs. "Terrifying."

"Real life," she says, leaning her head on his shoulder.

There are no more twists, no surprise reversals. No one dies onscreen. The only deaths that matter are the ones that happened before the story began: the death of his wife, the death of his certainty that he would never love again. Everything else is about things coming to life: his heart, his daughters' trust, his brother's capacity to forgive, a family's ability to expand to include new people without fracturing.

The final images are simple and domestic: Dan and Marie dancing; the girls weaving around them; Mitch and Ruthie laughing. The camera lingers on the collective--this large, messy, imperfect family that has weathered a weekend of secrets and confessions and come out the other side still intact, perhaps even stronger. There are no more secrets to hide, nothing left unrevealed. Dan in Real Life, the columnist, has finally allowed Dan in real life, the man, to follow his own hard‑won advice.

What is the ending?

In the ending of "Dan in Real Life," Dan finally confronts his feelings for Marie, leading to a heartfelt moment of connection. He realizes the importance of being true to himself and his emotions. The film concludes with Dan embracing his role as a father and finding a sense of peace and happiness in his life.

As the film approaches its conclusion, we find Dan, played by Steve Carell, grappling with the emotional turmoil that has unfolded throughout the story. After a series of misunderstandings and conflicts, Dan is at a crossroads. He has been navigating the complexities of single parenthood while also dealing with the unexpected feelings he has developed for Marie, portrayed by Juliette Binoche, who is also his brother's girlfriend.

The scene shifts to a family gathering at the beach house, where Dan's family is present. The atmosphere is filled with a mix of tension and anticipation. Dan's brother, Mitch, is oblivious to the emotional undercurrents, and the family is engaged in their usual banter. Dan, however, is lost in thought, reflecting on the events that have transpired. He feels the weight of his responsibilities as a father to his three daughters, while also grappling with his feelings for Marie.

In a pivotal moment, Dan decides to confront his emotions. He finds Marie outside, where she is looking out at the ocean. The sun is setting, casting a warm glow over the scene, symbolizing the hope and possibility of new beginnings. Dan approaches her, and they share a candid conversation about their feelings. Dan expresses his confusion and the struggle he has faced in reconciling his attraction to her with his loyalty to his brother. Marie, in turn, reveals her own feelings, acknowledging the connection they share.

As they talk, the tension begins to dissipate, and a sense of understanding emerges between them. Dan realizes that he cannot deny his feelings any longer. He takes a deep breath, and in a moment of vulnerability, he leans in to kiss Marie. This kiss is not just a culmination of their romantic tension but also a moment of clarity for Dan. He understands that he deserves happiness and that it is okay to pursue love, even amidst the complexities of family dynamics.

The scene transitions to a family dinner, where the atmosphere is lighter. Dan's daughters are engaged in playful banter, and the family is enjoying each other's company. Dan, now more at ease, embraces his role as a father with renewed vigor. He shares a laugh with his daughters, and there is a palpable sense of joy in the air. The camera captures the warmth of the family dynamic, highlighting the importance of connection and support.

In the final moments of the film, Dan is seen walking along the beach with his daughters, who are playfully splashing in the water. The sun is setting, casting a beautiful orange hue across the sky. Dan looks content, having found a balance between his responsibilities as a father and his pursuit of personal happiness. The film closes with a sense of hope, suggesting that while life may be complicated, love and family remain at its core.

As for the fates of the main characters, Dan emerges with a renewed sense of purpose and happiness, having embraced his feelings for Marie. Marie, too, finds herself at a crossroads, having navigated her own emotions and the complexities of her relationship with Mitch. Mitch, unaware of the full extent of the situation, continues to be a supportive brother, albeit with a hint of naivety regarding the dynamics at play. Dan's daughters are left with a father who is more present and engaged, fostering a loving environment as they move forward together. The film concludes on a note of optimism, emphasizing the importance of love, family, and the courage to pursue one's true feelings.

Is there a post-credit scene?

The movie "Dan in Real Life," produced in 2007, does not have a post-credit scene. The film concludes with a heartfelt resolution to the story, focusing on Dan's journey of self-discovery and the rekindling of his relationship with his family. After the main events unfold, the film wraps up without any additional scenes during or after the credits. The ending emphasizes themes of love, family, and moving forward, leaving the audience with a sense of closure.

What role does the family gathering play in the development of the plot?

The family gathering at the Burns' family home serves as the backdrop for much of the film's action. It is during this time that the characters interact, conflicts arise, and relationships are tested. The gathering highlights the chaos and warmth of family life, providing a setting for Dan's emotional journey as he confronts his feelings for Marie, deals with his daughters' issues, and ultimately seeks to find a balance between his responsibilities as a father and his own desires.

What is the relationship between Dan and his children?

Dan Burns, played by Steve Carell, is a widowed father of three daughters: Jane, Cara, and Lilly. Throughout the film, Dan struggles to connect with his daughters, who are navigating their own teenage challenges. He is protective and caring, often trying to balance being a father while also dealing with his own grief and loneliness. His relationship with them is central to the story, showcasing both the joys and difficulties of single parenthood.

How does Dan meet Marie, and what is their initial interaction like?

Dan meets Marie, portrayed by Juliette Binoche, at a bookstore while he is on a trip to visit his family. Their initial interaction is warm and flirtatious, filled with a sense of serendipity. Dan is immediately drawn to her, and they share a deep conversation that reveals their mutual interests and vulnerabilities. This encounter sets the stage for the emotional conflict that arises later in the film.

What complications arise when Dan discovers Marie's connection to his family?

The complications arise when Dan learns that Marie is actually the girlfriend of his brother, Mitch. This revelation occurs after Dan has developed feelings for her, leading to a mix of confusion, jealousy, and frustration. Dan's internal struggle intensifies as he grapples with his emotions for Marie while trying to respect his brother's relationship, creating a tension that drives much of the film's narrative.

How does Dan's relationship with his brother Mitch affect the story?

Dan's relationship with his brother Mitch, played by Dane Cook, is strained and competitive. Mitch is charming and carefree, which contrasts sharply with Dan's more serious and responsible demeanor. This dynamic creates tension, especially when it comes to Marie. Dan feels overshadowed by Mitch's charisma, and this rivalry complicates their family interactions, particularly as Dan tries to navigate his feelings for Marie while maintaining family harmony.

Is this family friendly?

"Dan in Real Life" is generally considered a family-friendly film, but it does contain some elements that may be objectionable or upsetting for children or sensitive viewers. Here are a few aspects to consider:

-

Themes of Loss and Grief: The film addresses the emotional struggles of a widowed father, which may resonate deeply and evoke feelings of sadness.

-

Romantic Complications: There are scenes that explore romantic relationships, including infidelity and the complexities of love, which may be confusing for younger viewers.

-

Family Tensions: The film depicts moments of conflict and tension within the family, including disagreements and misunderstandings that could be uncomfortable for some.

-

Mature Humor: Some jokes and situations may include adult themes or innuendos that might not be suitable for younger audiences.

-

Emotional Vulnerability: Characters experience moments of vulnerability and emotional breakdowns, which could be distressing for sensitive viewers.

Overall, while the film has a heartwarming core, these elements may require parental guidance for younger audiences.