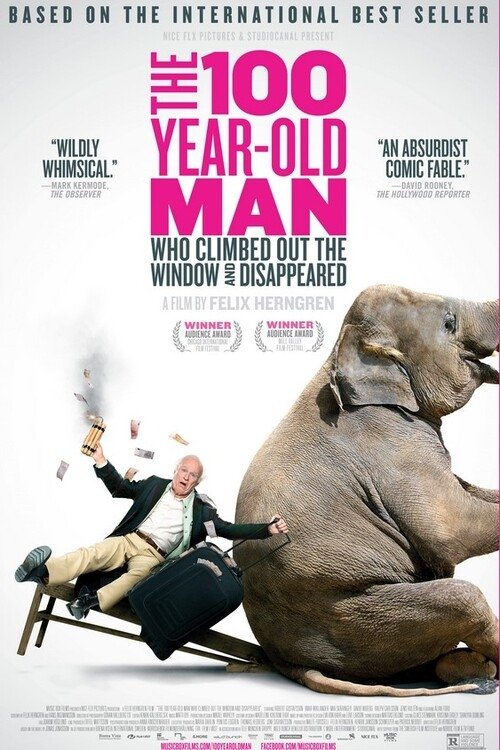

Ask Your Own Question

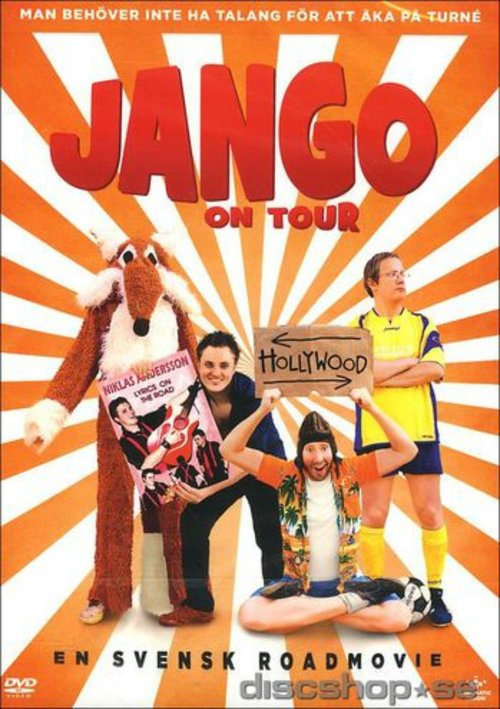

What is the plot?

Allan Karlsson is one hundred years old, and he has decided that today, the day of his own centenary, is far too important to spend in a Swedish retirement home dining hall under fluorescent lights.

It is the morning of his birthday in 2005, in the small town of Malmköping. Outside his window the sky is pale and washed‑out; inside, the home's staff have already begun fussing with streamers and a big banner that reads "Grattis på 100‑årsdagen!" on the far wall. They have arranged for a priest, a cake, some local politicians, the other residents. They think they are honoring him. To Allan, the party is a prison sentence with marzipan.

He sits on the edge of his narrow bed in his dressing gown and slippers, looking at the closed door, then at the open window. The memory of another explosion flickers behind his eyes: his small red wooden house out in the country, his cat Molotov's mangled body, the fox, the dynamite that turned half his garden into a crater. That blast is why he is here now.

He had lived alone with Molotov in that house, a content old man with a wood stove, a radio, and a cupboard where sticks of dynamite sat as naturally as sugar and flour. When the fox killed Molotov in the yard, Allan's grief runs so cold it feels matter‑of‑fact. "You shouldn't have done that," he tells the animal's fading tracks in the soil. He rigs a simple trap: a piece of meat wired to a bundle of dynamite in a metal bucket, a fuse running through the grass. That evening, the fox returns; there is a flash and a concussive bang. The fox dies instantly, torn apart by the explosion Allan has created. The fireball lights the sky; the neighbors call the authorities.

The next morning, uniformed men stand where the fox once did. They look at the crater, at the splintered fence, at the old man quietly stirring sugar into his coffee on the porch. They make notes. Words like "dangerous," "senile," and "institutional care" pass between them. Allan says, with a shrug, "The fox started it."

A week later they move him to the Malmköping retirement home against his wishes. He brings nothing of Molotov or his dynamite. He tells himself he will die soon and that will be that.

But now, sitting on this unfamiliar bed, he realizes something: he has woken up alive again, and that is intolerable if the only thing ahead is cake and speeches. Down the hall he hears the staff rehearsing where the mayor will stand for his little speech. Someone mentions that Allan never smiles. A nurse knocks on his door; when there is no reply, she continues on.

Allan looks again at the window. It opens onto a small patch of grass and a low wall. It is not that high. Slowly, like a child about to sneak candy, Allan swings his legs over the sill, feels the cold outside air on his bare calves, and lets himself drop, landing with a soft grunt on the lawn. His slippers sink slightly into the damp earth.

He pauses only long enough to straighten up and mutter, almost cheerfully, "So, let's see where we end up." Then he shuffles away toward town.

While inside the home they set out plates and light the candles shaped like "1" and "0" and "0," Allan walks in a straight line, stepping over low fences, cutting through gardens, startling a dog behind a chain‑link fence. He does not look back. By late morning he reaches the Malmköping bus station, a modest concrete building with large glass windows and plastic seats.

He has only a few coins in his pocket. At the ticket counter he asks the clerk, "How far can I go for this?" and empties the coins into the tray. The clerk, puzzled but not unkind, clacks at her keyboard and tells him the furthest that sum will take him is Byringe, a remote little place down the line. Allan nods and buys the ticket. Any destination will do.

The station is almost empty. A bus idles outside. Allan lowers himself carefully into a seat to wait when the entrance doors hiss open and a young man stomps in.

The man is a skinhead, lean and angry, with a bomber jacket, heavy boots, and a large gray suitcase in his hand. His name, though Allan does not yet know it, is Bolt, a violent errand‑boy for a criminal outfit. He is in a hurry, sweating and sniffling, looking back over his shoulder as if expecting someone to follow.

He spots Allan, alone, old, slow, and thus convenient. He walks up, slams the suitcase down beside the old man's legs and snarls, "Watch this," clearly more an order than a request. Without waiting for an answer, he adds a roughly muttered, "Don't you dare touch it," and strides off toward the toilets.

Allan looks at the suitcase. It sits there like an obedient dog. He does not particularly intend to watch it, but he is sitting there and it is sitting there and that is that. He folds his hands over his thin knees and waits. Bolt disappears into the restroom.

Outside, the bus driver opens the luggage compartment and calls for passengers. The bus to Byringe is ready to depart. Allan hears him. He looks once toward the toilets. Bolt does not come out. Allan picks up his ticket, then looks down at the suitcase again.

It is there. Allan is going to the bus. The bus will not wait forever. The decision is not really a decision at all. Allan stands, grips the handle of the suitcase with both hands – it is very heavy – and drags it. The rubber wheels squeak on the tile as he hauls it out of the station, across the platform, and up to the bus. The driver helps him stow it in the undercarriage, not asking questions. Allan climbs on, finds a seat.

By the time Bolt bursts out of the restroom and sees the empty seat where his suitcase had been, the bus door is already closing. He runs, screaming, but the driver only shrugs and pulls away.

On the other side of the glass, Allan watches the town recede. Behind, in Malmköping, a nurse opens his bedroom door, sees an empty bed, and drops the tray of coffee cups in shock. At the same moment, Bolt stands in the bus station, veins bulging, and yells a string of curses that make the woman at the ticket counter flinch.

From this quiet collision of incompetence and fate, the rest of the story unfolds.

On the bus, the sway of the vehicle and the hum of the engine lull Allan. He thinks of other rides, other transports, other authorities who thought they could contain him. His life stretches back a century, and his memories start to unspool.

He is a boy again, somewhere in Sweden in the early twentieth century. His father is a hot‑tempered socialist. At a protest, Allan hears him shout at the authorities that "people in higher places are not necessarily more intelligent." He means it. He means it so intensely that after a political quarrel, he ends up exiled and later dies in a foreign land, long before Allan turns grown. Allan learns two things from this: politics are dangerous, and explosives much more satisfying.

As a young man he discovers dynamite the way some boys discover music. It fascinates him. It obeys him. And very early, that fascination kills someone.

His mother once sends him to buy meat from a local butcher. The butcher cheats her, gives short weight. Allan, furious on her behalf, later rigs a little device in the butcher's shop as a kind of lesson, meaning to blow up some property, frighten him, maybe scorch his sign. Instead, his amateur arrangement goes wrong. When the fuse burns down, the explosion is larger than he intended. The shopfront disappears in a roar of flame and shattered glass; the butcher is killed outright, torn apart by the blast Allan has caused.

The authorities arrest him. The court hears of the boy's fascination with dynamite and concludes he is not criminal so much as mad. They send him to a mental hospital, where white‑coated doctors try to pry ideology out of him that he does not even have: Why did you do it? What did you want to prove? Allan does not understand the questions. He just likes things that go boom.

Years pass in the institution. Eventually, someone decides he is harmless enough if pointed in a useful direction. There is a war on, after all. Factories need hands. They release him into work at a cannon foundry, where the heat of molten metal and the clang of steel are like a new language he already knows.

It is there, among the cannon barrels and the soot, that Allan meets Esteban, a passionate Spaniard who rails about General Franco and fascism. Esteban calls him "compañero" and talks late into the night about the need to fight oppression. Allan listens kindly, drinks, and mostly thinks about how the cannons could be improved.

When Esteban leaves for Spain to join the fight in the Spanish Civil War, he persuades Allan to come along and help with explosives. Allan goes not because he believes in the cause but because it sounds like an interesting job. In Spain, he watches as shells he has helped perfect arc through the sky and detonate, shredding men he has never met. The flags change, the slogans change, but the sound of an explosion is the same.

Decades later, in the United States, he will wander into the orbit of Robert Oppenheimer at a crucial moment. In a bustling lab in New Mexico, the American physicist paces before a blackboard filled with incomprehensible equations, muttering that something is not working. Allan, visiting as an uncredentialed "expert in practical blasting," watches for a while. Then he pipes up, in his flat Swedish tone, "Have you tried changing the shape?" and gestures toward the sketch of a spherical system.

Oppenheimer stares, realizes the simplicity and brilliance of the suggestion – an insight into creating a working implosion device – and within months the world will have the atomic bomb. Allan himself is more interested in the sandwiches at the lab cafeteria. He shares a drink with Harry S. Truman, later the President, who laughs at the frank Swede and calls him "Al." They become, in their way, friends.

In Moscow, Allan sits across from Joseph Stalin at a long table during a brittle dinner. Stalin wants to harness Allan's knowledge of explosives, perhaps for nuclear ambitions of his own, and expects ideological loyalty in return. Allan, though, does not play that game. Over vodka, he makes an offhand comment that betrays his indifference to communism and capitalism alike. He might say something like, "Explosives don't care who's in charge," and chuckle.

Stalin does not chuckle. His mustache twitches. Offended, he has Allan arrested. The charge is vague: sabotage, counter‑revolutionary behavior, insolence – it hardly matters. Allan is packed into a train car heading east, to a Siberian labor camp.

On the way to Vladivostok, shivering among other prisoners, Allan meets a tall, nervous man with wild hair who introduces himself as Herbert Einstein, half‑brother of Albert. The Soviets, in a mix of ambition and incompetence, have kidnapped the wrong Einstein, and now they do not know what to do with him. Herbert is terrible at physics, but good at being frightened.

At the camp, Allan endures five years of cold, hunger, and pointless labor. He misses one thing more than any ideology: vodka. Eventually, that craving, and his basic refusal to accept that any authority can really hold him forever, pushes him to plan an escape. With Herbert, he works out a way to slip past inattentive guards, exploit a hole in the barbed wire, and vanish into the snow.

They do; one night, in a hard, glittering frost, they run. The guards curse and fire rifles into the dark, but the bullets miss. Somewhere down the line, western intelligence services notice that this Swede who has been close to Oppenheimer and Stalin and survived a Soviet gulag is now wandering free. The CIA meets him later, in some gray office, and recruits him, almost out of reflex. A man who bears no ideology is, paradoxically, a perfect double agent. Allan nods politely, takes whatever job offers keep coming, and never once pretends he believes in anything but food, sleep, and explosions.

All of this lives in Allan's mind like someone else's biography as the bus rolls toward Byringe. When they arrive, he gets off, retrieves the heavy gray suitcase with the driver's help, and steps into a mostly empty rural station in a place that is little more than a signpost and a stretch of forest.

He is not alone for long. That suitcase, though Allan still does not know it, contains millions in criminal money – in some tellings around the equivalent of five million dollars. Bolt's bosses, members of the violent Never Again gang, are now fully aware that their courier lost the cash to an unknown old man on a bus. Their leader, a thug named Bucket in some accounts, sends out enforcers. Among them is Pike, another hardcase who will become important later.

Back in Malmköping, the retirement home staff panic when they realize their hundred‑year‑old guest of honor is missing. They call the police. Inspector Aronsson, a middle‑aged, competent but overworked cop, takes the report. At first, it is just a missing‑persons case: an elderly man, confused, may have wandered off. Aronsson has no idea that the case will soon involve dead gangsters, a missing fortune, and international bodies turning up in remote places. He sends out notices, alerts bus drivers, starts his search.

In the present, Allan finds someone else first. Wandering from the Byringe stop, hauling the suitcase, he stumbles onto a small property where Julius lives – a slightly shabby, street‑wise man used to making do with little. Julius sees the old man with the heavy case and smells opportunity, but also feels a kind of unexpected camaraderie. They strike up a conversation.

"What's in the suitcase?" Julius asks.

"I don't know," Allan replies truthfully. "It was there, so I took it with me."

They pry it open and stare. Bundles of cash fill the interior, stuffed to the brim. The sight stuns Julius; Allan mostly blinks.

"Someone will want this back," Julius says carefully.

"Then why did they leave it with me?" Allan answers. It is hard to argue with that logic.

Julius, seeing both danger and the possibility of a life‑changing windfall, persuades Allan that they should move quickly, hide, and maybe keep the money. Allan shrugs. Why not?

As they improvise their escape, the Never Again gang's search begins. Bolt, desperate, has reported his mistake. His boss rages. Men are dispatched to Byringe, to Malmköping, to every bus line and café along the route.

In parallel, Aronsson's investigation picks up a stray detail: a witness at the Malmköping station remembers an old man boarding with a big gray suitcase that did not look like his. The inspector notes it and starts adding lines on his board from "Missing centenarian" to "Unidentified property."

Meanwhile, in the clumsy, violent world of the gang, things start to go lethally wrong. One gang member, sent to track down the suitcase and Allan, ends up trapped in a freezer – killed by misadventure, his body later shipped out of the country in a container bound for Djibouti. Another henchman dies more grotesquely: in a chaotic confrontation involving an elephant named Sonya, he is crushed to death, his remains later discovered in Latvia after a convoluted trip in the trunk of a Ford Mustang. In the film, these individual deaths are played as darkly comic, the camera lingering more on the absurd logistics than the horror, but the facts are clear: the gang is being decimated by sheer bad luck and the unpredictable chain reaction Allan has set off. Each of these deaths is indirectly caused by Allan's presence and the suitcase he "stole," aligning with his lifetime pattern: he rarely kills someone directly, but fate does a lot of work around him.

Allan and Julius, now accidental fugitives with criminal millions, pick up companions along the way in the present‑day storyline. One is Benny, a perpetually failing student who has studied everything but finished nothing, a man of countless half‑degrees. Another is Gunilla, known as "The Beauty," who lives on a small farm with her elephant Sonya. Together, the mismatched group – centenarian explosives expert Allan, petty criminal Julius, professional dropout Benny, strong‑willed Gunilla, and the lumbering Sonya – travel through Sweden in beat‑up vehicles, hiding and improvising, always a step ahead of the enraged gang and the puzzled police.

The first time the gang catches up to them, the confrontation is tense but almost slapstick. A sweating enforcer shouts and waves a pistol; Sonya trumpets; Benny trips over a hose; Allan, completely calm, looks at the gun and says something like, "You'll have to shoot, or we'll be late for dinner." The gunman hesitates; events cascade; the elephant shoves, a vehicle rolls down an incline, and someone dies by accident rather than design. Each time violence erupts, Allan is not frightened, just vaguely inconvenienced.

Inspector Aronsson, on the other hand, grows more and more frustrated. He discovers bodies linked to the Never Again gang – a corpse that once was Bolt, turning up in Djibouti; another that was Bucket, surfacing in Latvia. How could a gang war in Sweden end with corpses scattered around the globe? Witnesses keep mentioning an elderly man and strange traveling companions. Aronsson begins to suspect that the missing Allan Karlsson and this inexplicable trail of criminal disaster are connected.

Back in Allan's past, the flashbacks keep intercutting with these present‑day misadventures. After the war, after his time in the U.S. and the Soviet Union, he finds himself sent to China, theoretically to help the Kuomintang forces fight communists, then drifting with communist partisans through the Himalayas toward Iran, then entangled in a plot that brushes up against Winston Churchill. Each time, he helps or hinders powerful men without intending to, often by suggesting some simple explosive solution that others overlook. Leaders trust him for a time, then are confused or angered by his refusal to take sides. He always slips away.

Eventually he tires of politics entirely and returns to Sweden. For a while, he lives quietly, no longer blowing up butchers or influencing world wars. He adopts the cat Molotov, names him after the Soviet foreign minister as a private joke, and settles into a peaceful life. Then, as we have already seen, the fox kills Molotov; Allan kills the fox with dynamite; the blast sends him to Malmköping. Past and present finally align.

In the present, Allan's group learns from a news report that the police have issued warrants for their arrest. They are now, officially, fugitives: Allan, Julius, Benny, and The Beauty are all wanted, suspected of involvement in theft, kidnapping, and perhaps murder. The thought of turning themselves in is discussed around a cramped kitchen table in a safe house.

"We could go to the police, explain," Benny suggests, rubbing his temples.

Gunilla scoffs. "Explain what? That an elephant sat on a gangster and that we borrowed their suitcase of millions by accident?"

Allan stirs his coffee and listens. Finally, he says, "It will sort itself out. It always does." The others look at him, half irritated, half reassured by his strange serenity.

The weight of their situation forces them to look for safer refuge. They travel to the home of Benny's estranged brother, Bosse, a man who has done better for himself and lives in a more respectable, solid house. The air between the brothers is brittle at first; they have not spoken in years. As a peace offering, and as a practical form of bribery, they offer Bosse $300,000 from the suitcase if he agrees to shelter them for a time. Bosse, torn between unease and greed, accepts.

Around the same time, Pike, the tough gang member who has survived where Bolt and Bucket have not, tracks them to Bosse's place. He enters the house carrying his pistol, prepared for a showdown. But when he steps into Bosse's kitchen, he freezes. Bosse stares back. Recognition flashes.

"Pike?" Bosse says, incredulous.

"Bosse? You old bastard!" Pike grins.

They are old friends, as surprised as anyone. Years before, their paths had crossed; they share history, stories, maybe once shared a cell or a scam. Whatever their past, it is warm enough that they embrace, pistol and all. The expected gunfight dissolves into backslapping and laughter. The immediate confrontation ends not with a death, but with shifting alliances.

By now, Inspector Aronsson has pieced together enough to locate Allan's group. However, circumstances change at the highest levels of the Swedish justice system. The national prosecutor, Ranelid, calls Aronsson with news: the corpses identified as Bolt and Bucket have been found, as noted, one in Djibouti, one in Latvia, both obviously dead and far from Swedish jurisdiction. A third suspected dead man, Pike, is assumed by the prosecutor to make a neat trilogy of gang casualties.

Aronsson, who at this moment is actually sitting in Bosse's house, across from a very much alive Pike, Allan, and the others, holds the phone away from his ear for a second and looks up. Pike meets his gaze and shrugs, perhaps nibbling on a cinnamon bun that Gunilla has set out.

"The third corpse you're looking for," Aronsson tells the prosecutor cautiously, "is not a corpse. He's alive and sitting in front of me."

There is a stunned silence on the line. The legal narrative that was starting to tidy itself up – three dead gangsters, case closed – collapses. The prosecutor, embarrassed at having already framed the story in a particular way, now faces a choice: pursue messy charges against an old man and his motley friends, or find a way to declare victory and back away.

He chooses the latter. Over the phone, he informs Aronsson that, given the confusion and the lack of clear evidence tying Allan's group to deliberate crimes, all charges will be dropped. He adds that he will come in person the next morning to meet them and finalize the matter. Aronsson relays the message.

That evening, in Bosse's living room, Allan and his companions sit together, processing what this means. They are, provisionally, free – but they must still get through an official interview with the prosecutor. They spend the night concocting an explanation for their actions, an account of the past weeks that is technically possible but wildly improbable. Part of them expects no one will believe it. Another part, especially Allan, suspects that belief is not even required; only a plausible story that allows the authorities to save face.

The next morning, Prosecutor Ranelid arrives. He is a man who likes order, logic, and paperwork that lines up. He sits at Bosse's table. Across from him are Allan Karlsson (100 years old, cheerful), Julius (nervous, eager to please), Benny (rumpled but articulate), Gunilla (calm but watchful), and Pike (awkward under official scrutiny). An elephant can be heard snorting somewhere in the background.

Allan pours coffee and offers pastries as if this were a casual neighborly visit. Inspector Aronsson, who has come to recognize the absurdity of the situation, lets the scene breathe. Ranelid asks them to explain themselves. How did they come into possession of the suitcase of criminal money? What about the missing gang members? The travels around Sweden?

Together, with Allan's deadpan contributions and Benny's flair for overcomplicated detail, they tell their story. It is a mixture of truths and omissions: an old man accidentally entrusted with a suitcase, a series of misunderstandings, chance encounters with an elephant, long‑lost friendships, freezers, and faraway shipping containers. Listening, Ranelid feels his hold on probability loosen. But he has already, on the record, declared them all innocent. To contradict himself now would be politically and professionally costly.

So he accepts their explanation – not because it is convincing, but because it is necessary. He signs the papers. The story, as far as the Swedish justice system is concerned, ends here. Allan and his companions are free citizens. The suitcase of money is, in practical terms, theirs.

Somewhere in the bureaucracy, the police formally call off the search for Allan Karlsson. In their files, he is now just a centenarian who left his retirement home, got mixed up in some confusion, and was later "found and cleared of wrongdoing." What they do not realize – what no official report ever captures – is that he was also at the center of the collapse of the Never Again gang and the loss of their fortune. Aronsson, who has seen more than most, chooses not to dig further. He leaves the house that day with a full stomach and a sense that justice, in some roundabout way, has been done.

For Allan, though, the adventure is not over. Sitting with his friends, contemplating their next steps, he feels the familiar restlessness. He is over a hundred years old. He has been in Spain and Russia and America and China and who‑knows‑where‑else. He has seen atomic bombs tested and Stalin rage and Truman drink. He has escaped mental hospitals and gulags and retirement homes. Now he has a suitcase with many millions and, for once, a circle of companions he likes.

They decide to leave Sweden.

With the help of Popov's son Oleg – Popov being a Soviet contact from Allan's Cold War days – they arrange passage far away, to a place where Swedish police, Swedish gangs, and Swedish retirement homes are distant abstractions. Oleg still has connections, still owes Allan favors. He makes some calls, greases some palms.

The group travels – through airports or more circuitous routes the film touches on briefly – until they arrive in Bali, an island in Indonesia that smells of sea salt and incense, where the air is warm even at night and nobody cares about Scandinavian arrest warrants. The money from the suitcase, converted into other currencies and laundered through Oleg's channels, funds their new life.

The final scenes unfold there. The camera pans over a luxury hotel or villa complex, sunlight flashing on a pool's surface, palm trees swaying. Allan sits at a table on a terrace, wearing light clothes more suited to the tropics than to Swedish winters, a drink in his hand. Beside him, Julius chats with Benny, arguing amiably about some trivial subject. Gunilla laughs, her hair ruffled by the breeze. Somewhere nearby, children play – possibly Amanda and her sons, managing the place as in the novel's parallel ending. The elephant Sonya might even be glimpsed, improbably but content, in a lush enclosure, munching on palm fronds.

No one here knows that this white‑haired man once suggested a key design to Robert Oppenheimer or insulted Joseph Stalin to his face. No one cares that he accidentally killed a butcher in Sweden many decades ago, or that a fox once died in a homemade explosion in his garden, or that a criminal gang called Never Again imploded partly because of him. As the narrator's perspective implies, Allan himself does not dwell on those details either. For him, life has always been about the next meal, the next nap, and perhaps the next carefully placed charge of dynamite.

As the sun sets, Allan leans back in his chair. The orange light paints his wrinkled face. Gunilla asks, "So, Allan, are you finally going to settle down?"

He considers it for a moment. "Maybe," he says. "Unless something interesting happens."

They laugh. The camera pulls away: a wide shot of the terrace, the pool, the palm trees, the ocean beyond. We understand, fully, how everything has turned out.

Molotov the cat is long dead, killed by a fox, which was in turn killed by Allan's dynamite. The fox's death led to the explosion that sent him to the retirement home, which led to his escape out of the window, which led to the bus station, the suitcase, the gang, the police. Along the way, the butcher from his youth died in an early, clumsy blast; multiple gang members met their ends through a series of accidental but fatal mishaps: one trapped in a freezer bound for Djibouti, one crushed by Sonya the elephant before being shipped to Latvia, others perishing in off‑screen confrontations gone wrong. Bolt and Bucket are specifically identified post‑mortem by the authorities; Pike, by contrast, survives to sit with Allan in Bosse's kitchen, then to perhaps share in Allan's tropical retirement. Globally, nameless soldiers and civilians died in wars in Spain, Korea, China, and elsewhere, sometimes using weapons and explosives that Allan helped refine. Their deaths are a somber backdrop to the film's comedy, never dwelt upon but ever‑present.

In the end, though, the film's focus remains on this single, hundred‑year‑old man who keeps slipping through the fingers of every power that tries to contain him. The Swedish police close his file; the Never Again gang is effectively destroyed; the authorities never reclaim the money. Allan Karlsson, who once climbed out of a window in Malmköping on the morning of his 100th birthday, now sits in Bali, alive, free, and surrounded by friends, his story ending not with institutional walls but with an open horizon and the unspoken promise that, if boredom ever threatens again, he will simply stand up and walk away.

What is the ending?

In the ending of "The 100 Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared," Allan Karlsson, the protagonist, finds himself in a final confrontation with the gangsters who have been pursuing him. After a series of comedic and chaotic events, he manages to outsmart them. The film concludes with Allan and his friends enjoying a peaceful moment, reflecting on their adventures, and Allan finally finding a sense of belonging and happiness.

Now, let's delve into the ending in a more detailed narrative fashion:

As the story approaches its climax, Allan Karlsson and his motley crew of companions--who include the bumbling criminals and the elderly friends he has made along the way--find themselves cornered by the gangsters who have been chasing them throughout their escapades. The tension is palpable as the gangsters, led by the menacing figures of the criminal underworld, close in on Allan and his friends in a remote location.

In a moment of sheer ingenuity, Allan, who has always been resourceful, devises a plan to turn the tables on his pursuers. He recalls his past experiences with explosives and uses his knowledge to create a diversion. The scene is filled with a mix of humor and suspense as Allan's friends, initially hesitant, rally behind him, showcasing their loyalty and newfound camaraderie. The gangsters, underestimating Allan's cleverness, fall victim to their own greed and incompetence.

As the chaos unfolds, explosions and comedic mishaps ensue, leading to a series of slapstick moments that highlight the absurdity of the situation. Allan's friends, including the elderly man who has become a father figure to him, display bravery and resilience, proving that age does not define one's ability to confront danger.

In the aftermath of the confrontation, the gangsters are left in disarray, and Allan and his friends emerge victorious. They share a moment of triumph, laughing and celebrating their survival. The camaraderie they have built throughout their journey is evident, and it becomes clear that they have formed a family of sorts, united by their shared experiences.

The film concludes with Allan finally finding a place where he feels he belongs. He and his friends settle down in a peaceful setting, enjoying the simple pleasures of life. Allan reflects on his long and eventful life, filled with adventures, friendships, and the wisdom he has gained along the way. The final scenes are filled with warmth and a sense of closure, as Allan embraces the joy of living in the moment, free from the burdens of his past.

In the end, Allan Karlsson, having outsmarted his adversaries and found companionship, embodies the spirit of resilience and the importance of friendship. His friends, who have stood by him through thick and thin, also find a sense of purpose and belonging. The film closes on a hopeful note, emphasizing that life can be full of unexpected twists, and it is never too late to find happiness and adventure, no matter one's age.

Is there a post-credit scene?

In the movie "The 100 Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared," there is no post-credit scene. The film concludes without any additional scenes or content after the credits roll. The story wraps up with the resolution of Allan Karlsson's adventures, leaving the audience with a sense of closure regarding his journey and the characters he encountered along the way. The focus remains on the narrative of Allan's life and his escapades rather than extending the story further in a post-credit sequence.

What motivates Allan Karlsson to climb out the window and leave the nursing home?

Allan Karlsson, a centenarian with a zest for life, feels stifled and bored in the nursing home. His desire for freedom and adventure, coupled with a sense of curiosity about the world outside, drives him to escape. He is also seeking to avoid the monotony of his current life and the impending birthday celebration that he has no interest in attending.

How does Allan's past influence his present journey?

Throughout the film, Allan's past is revealed through flashbacks that showcase his extraordinary life, including encounters with historical figures and involvement in significant events. These experiences shape his character, making him resourceful and adaptable. His past adventures provide him with the skills and confidence to navigate the challenges he faces during his journey after escaping the nursing home.

What role do the criminals play in Allan's adventure?

The criminals, who are initially a group of bumbling thieves, become entangled in Allan's journey when he inadvertently steals a suitcase filled with money from them. Their pursuit of Allan adds a layer of comedic tension to the story, as they are often outsmarted by Allan's cleverness and luck. This interaction highlights Allan's ability to remain calm and resourceful in unexpected situations.

How does Allan's relationship with the other characters evolve throughout the film?

As Allan travels, he forms unexpected friendships with the other characters he meets, including the criminals and a young man named Julius. These relationships evolve from initial distrust or indifference to camaraderie and mutual support. Allan's kindness and wisdom influence those around him, leading to personal growth for both him and his companions.

What is the significance of the suitcase Allan takes with him?

The suitcase Allan takes is significant as it symbolizes both opportunity and adventure. It contains a large sum of money, which becomes a catalyst for the events that unfold. The suitcase represents Allan's unexpected turn of fortune and the new possibilities that arise from his decision to escape the nursing home, ultimately leading to a series of comedic and life-changing encounters.

Is this family friendly?

The 100 Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared is generally a light-hearted comedy, but it does contain some elements that may not be suitable for all children or sensitive viewers. Here are a few potentially objectionable or upsetting aspects:

-

Death and Mortality: The film touches on themes of death, as the protagonist reflects on his long life and the people he has lost. There are scenes that depict the aftermath of death, which may be unsettling for younger viewers.

-

Violence: There are moments of mild violence, including scenes involving explosions and confrontations with criminals. While these are often played for comedic effect, they may still be alarming to some.

-

Alcohol Consumption: The main character and others are shown drinking alcohol throughout the film, which may not be appropriate for younger audiences.

-

Mature Themes: The story includes discussions about war, political intrigue, and some dark humor that may not resonate with children or those sensitive to such topics.

-

Language: There are instances of mild profanity and crude humor that might not be suitable for all viewers.

Overall, while the film is comedic and whimsical, these elements may warrant parental guidance for younger audiences.