Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

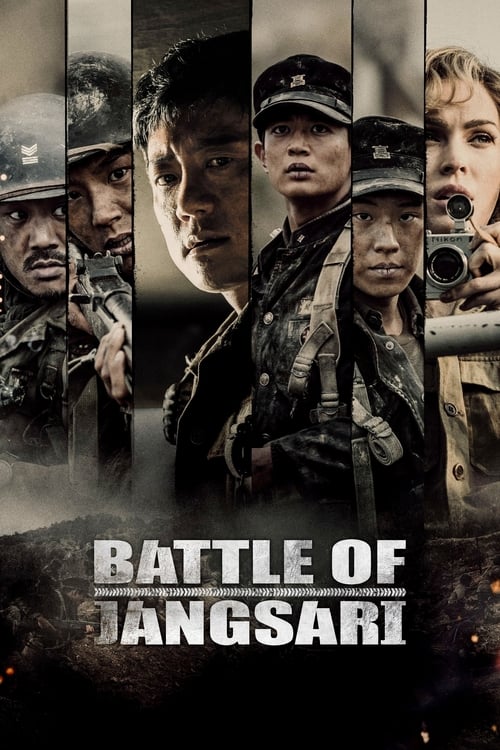

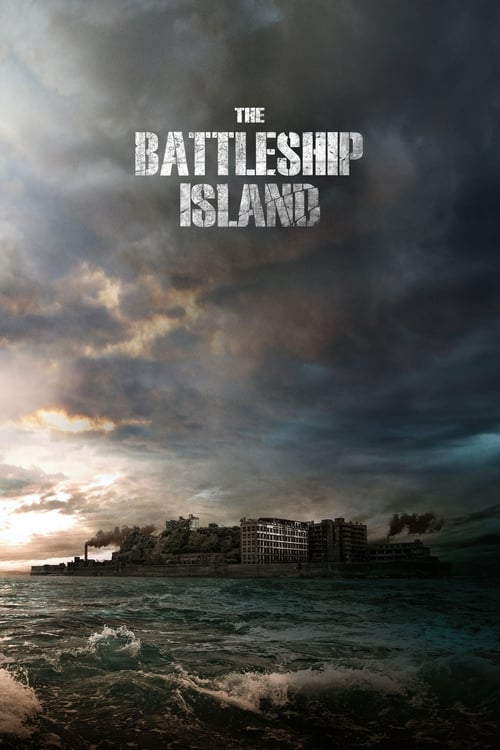

The story opens in darkness, the low thrum of engines shuddering through steel. It is the predawn hours of September 14, 1950, in the churning waters off the east coast of the Korean peninsula. A troop transport ship pushes through rough seas toward a stretch of coast called Jangsari Beach, near Yeongdeok village in South Korea. Inside its dim hold, rows of boys in oversized uniforms sit shoulder to shoulder, helmets askew, rifles clutched in nervous hands.

They look like soldiers, but their faces betray them: acne, thin shoulders, restless eyes. They are the Independent 1st Guerrilla Battalion--772 student volunteers, most still in high school, with an average age of 17, and only two weeks of boot camp training behind them. They whisper, jostle, and try to joke away the fear that presses in along with the stench of fuel and salt and sweat.

At the center of the chaos stands Captain Lee Myung-joon, a weary, stern-eyed ROK officer in his thirties. He moves down the line with a clipboard and a cigarette, checking gear, correcting a grip here, adjusting a strap there. He knows, far better than the boys do, what awaits them on that black strip of coastline. But his voice stays level.

"Check your ammo. Check your helmets. Once that door opens, you run. You don't stop," he orders, the words clipped and automatic, as if discipline can hold back bullets.

Among the boys is Choi Sung-pil, a wiry student with sharp, searching eyes and the easy authority of someone other kids naturally follow. He has been made a student squad leader, and he tries to look braver than he feels. Beside him sits Ki Ha-ryun, talkative, impulsive, who keeps pressing up against everyone's nerves with his chatter.

"You know how many letters I got from girls before we shipped out?" Ki Ha-ryun grins, elbowing the boy next to him. "Ten. All wishing me luck. After the war, I'll have to pick one. Maybe two."

There is a ripple of laughter, thin but genuine. Someone mutters, "You'll be lucky if any of them remember your name." Another boy fires back, "He's lying. No girl would write to that face." The banter wobbles, then steadies, a flimsy dam against the dread rising in their throats.

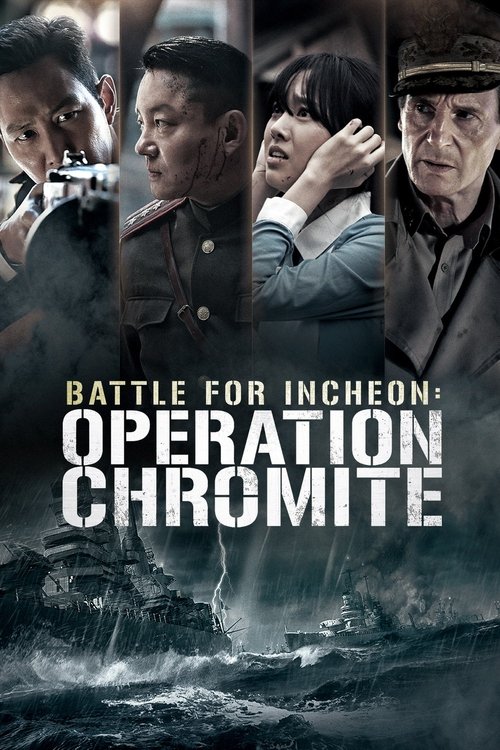

On the upper deck, the wind is a shrieking wall. Captain Lee joins the ship's crew at the rail, peering through binoculars toward the invisible shore. The night is swollen with cloud; the seas are heavy, the weather bad, spray smashing over the bow. Somewhere inland, he knows, the North Korean lines press down toward the Pusan Perimeter, where South Korean and UN troops are barely holding on. Far to the west, Incheon waits for General MacArthur's Operation Chromite, the grand amphibious assault that is supposed to turn the tide of the war.

Their role is small but lethal: a diversionary landing at Jangsari Beach, territory already conquered and fortified by North Korean soldiers. Their mission is to strike supply routes, sow confusion through hit‑and‑run attacks, and convince the North that the main invasion will happen here, not at Incheon. It is a mission designed to be expendable.

"Radio?" Captain Lee asks curtly.

"Still intermittent, sir. Signal keeps dropping in this weather," a crewman answers, tapping the bulky radio equipment with frustration. The static that hisses from it is continuous, merciless.

Far away, in American military headquarters, harsh fluorescent lights hum over maps and ashtrays. On a large wall map of the peninsula, colored pins mark Incheon, Busan, Jangsari. General Stevens, a compact, controlled American officer with tired eyes, stands before it, jaw clenched. His staff brief him on the independent student unit moving toward Jangsari. The intel reports are bare: "Minimal training, minimal equipment, diversionary objective."

"Orders from above?" Stevens asks.

"Mission is classified. Unit is deniable," an aide replies.

Stevens stares at the map, at that small pin on the east coast. He understands what "deniable" means. It means those 772 boys are meant to be sacrificed--their blood the price of surprise at Incheon.

In a corner of the bustling press room outside, Maggie, an American war correspondent played by Megan Fox, types furiously at a portable typewriter. Her dispatch describes the refugee columns, the burned-out villages, the desperate South Korean retreat. She has heard rumors of a "student battalion" sent into combat. No one will give her details. The censors slash her copy; her story dies on the editor's desk.

She storms into Stevens's office, credentials in hand. "General Stevens, sir, I need confirmation. Are you deploying student volunteers to the front?"

"Ms. Miller," he replies evenly, "I can't discuss operational details with a civilian."

"These aren't 'details.' These are children," she insists. "If there's a unit of teenagers going into a combat landing, the world deserves to know."

Stevens hesitates. For a moment, his professional mask falters. "We are fighting for the survival of an entire nation. Difficult choices have to be made."

"You mean you're sending them to die so MacArthur can have a cleaner landing," she fires back.

He looks away, then down at the stack of orders on his desk. "You have your job, Ms. Miller. I have mine."

The ship nears Jangsari Beach. Dawn is still a rumor behind black clouds. Waves hammer the hull. Within the hold, the ramp door looms, ominous. Ropes are coiled on the floor--thick, rough lines that the crew will use because many of the students cannot swim, and the water between ship and shore is deep and violent.

Captain Lee steps into the center of the soldiers. "Listen up! When that door opens, there will be enemy fire. Do not stop. Do not look back. You grab the ropes, you move forward. If you fall, you get up. If you can't get up, the man behind you pulls you. Is that clear?"

A murmured, shaky chorus: "Yes, sir."

He searches their faces--Choi Sung-pil standing a little straighter, Ki Ha-ryun nervously licking his lips, dozens of others staring with huge, frightened eyes. Many of them will die in the next five minutes. He knows it. He shoves it down.

The ramp slams open with a teeth-rattling clang--and hell explodes inward.

Cold seawater surges into the hold as the ship rocks. The first line of boys lurches forward--and instantly North Korean machine guns tear into them from concealed positions along the shore. Bullets rake the open mouth of the transport, punching through helmets and bodies. The adult sailors and noncommissioned officers leading the rope teams are hit first, shredded, thrown backward in arcs of blood. Boys behind them slip on the suddenly slick deck.

"Go! Move, move!" Captain Lee roars, pushing them bodily toward the surf.

On the far Jangsari shoreline, faint grey light reveals North Korean bunkers and gun nests dug into the sand and rocks. They fire in relentless bursts, tracers stitching lines across the churning water. The scene echoes Normandy in Saving Private Ryan--but these are Korean teenagers, stumbling out into waves that reach their chests.

The crew throws ropes into the water, anchoring them to the ship and shouting for the students to grab on. Choi Sung-pil volunteers to help one of the adult team leaders, leaping into the surf to secure a line closer to shore. As he struggles with the rope, the adult beside him jerks suddenly, riddled with bullets, and collapses into the waves, face down. Blood ferries away in the foam.

"Sergeant!" Sung-pil yells, grabbing at the sinking body, but another burst of bullets drives him down. He hauls the rope with frantic strength, securing it under fire, barely surviving as water and bullets slam around him.

Behind him, boys tumble into the sea, clutching the line. Some scream as bullets hit; others sink without a sound. Those who cannot swim flail, dragged under by their own gear. A boy reaches for the rope, misses, and is pushed away by a wave; a machine gun burst cuts him apart before he can surface again. The water turns dark with blood and floating packs.

Onshore, a hidden North Korean machine gunner--a young man barely older than his targets--sweeps his weapon in cold, practiced arcs. He mows down one student after another. Amid the chaos, a South Korean student sniper--another of Captain Lee's boys--forces himself onto a rocky outcropping, lying prone, rifle braced. His hands shake violently.

"Take the shot!" his friend yells from behind cover.

The sniper sights the North Korean gunner. Through the scope, he sees not a faceless enemy, but a young Korean face squinting down iron sights. For a second, he freezes, finger trembling on the trigger.

"Shoot, damn it!" his squad mate screams.

He fires. The bullet slams into the gunner's chest. The man jerks, collapses in the nest. The machine gun falls silent. On the beach, a small pocket of fire ceases, giving the struggling students a thin corona of safety. Some of them crawl higher up the sand, coughing, dragging each other.

Later, once he reaches the sand and the immediate storm ebbs, the sniper picks his way through the bodies, following a trail of spent shell casings. He finds the North Korean soldier he killed lying twisted beside his machine gun. The man's jacket is open; inside is a small, worn photo of a young wife and a baby. For a long, stunned moment, the sniper stares.

"He… he had a family," he whispers, voice cracking. His friend says nothing. The understanding settles like lead: North or South, these are all Korean boys.

The initial assault is a massacre. Many of the adult officers and sailors leading the ropes die in the water, cut down by machine gun fire. Scores of students die before even touching sand, their bodies floating between ship and shore. On the beach, craters of sand fill with still forms in schoolboy boots and army-issue belts.

But enough make it. Gasping, vomiting seawater, pushed by fear and raw survival instinct, they surge up the beach in short, stumbling rushes. They throw themselves behind the sparse cover of rocks and half-buried tank traps. Captain Lee fights at the front, barking orders, pointing targets, steadying what little discipline he can salvage.

He directs mortar fire, such as they have, calls for grenades on the nearest bunkers. One after another, small North Korean positions are assaulted and cleared by these soaking, trembling teenagers. In brutal close-quarters fighting in trenches and dugouts, bayonets thrust, grenades explode, and both sides leave dead scattered in sand-streaked uniforms.

They take the North Korean base overlooking Jangsari Beach, killing or forcing the retreat of the defenders. Some North Korean soldiers fall in firefights; some die under grenades lobbed into pillboxes; some are bayoneted as they try to flee. The film often shows the consequence but not always lingers on each individual death. The student soldiers, shocked at the blood on their own hands, realize there is no way back to being who they were.

Once the immediate enemy fire is suppressed, the boys begin to consolidate. They drag their dead comrades into rough rows, stripping weapons and ammunition from their bodies. The cost of the landing is horrific: bodies litter the tide line, some already being pulled back out to sea. Dozens, perhaps over a hundred, have died in the first assault alone, but the film emphasizes not the numbers, rather the raw emotional toll written on the survivors' faces.

The radio equipment they brought ashore is hauled up the dunes and hastily set up in a makeshift command post in the captured base. It crackles with static, occasionally catching a snatch of a transmission, then dropping it again. They attempt to call for air support and resupply, but the radio doesn't work properly, the weather and damage rendering them close to isolated. The air support that was meant to soften Jangsari arrives too late, after most of the worst has already happened.

Over the next hours, Captain Lee and his small cadre of surviving adult NCOs organize patrols inland. Their objective is to block supply routes and carry out hit‑and‑run attacks on North Korean logistics, contributing to the larger plan to disrupt the North Korean Army around the Pusan Perimeter.

In a nearby village, shattered by earlier fighting, they encounter a ragged group of North Korean soldiers retreating along a road. A firefight erupts in narrow streets and among crumbling houses, gunfire snapping between stone walls. Windows shatter; chickens burst from coops, screaming.

In one house, a South Korean student soldier--call him Young-bok, one of the unnamed but emotionally central boys--kicks open a door and confronts a North Korean private who has dropped his rifle and is raising his hands. As Young-bok's squad fans in, someone recognizes the prisoner.

"Cousin?" Young-bok breathes, stunned.

The captured North Korean soldier looks at him with the same shock. They are family--separated by the arbitrary line of the 38th parallel, now facing each other as enemies.

The rest of the squad storms in behind Young-bok and quickly disarms several other North Korean prisoners they've rounded up in the skirmish. The mood is tense; these are boys whose friends were just killed on the beach. One student spits, "Commie bastards. We should shoot them now."

Another grabs his rifle, pointing it at the line of prisoners kneeling on the floor. Several of the North Koreans flinch; one begins to pray under his breath. Young-bok instinctively steps between his cousin and the gun barrel.

"Stop! He's my cousin!" he shouts.

"So?" another boy snaps. "They killed our friends."

The camera lingers on the muzzle of the rifle, on Young-bok's hand shaking as he pushes it away, on the cousin's terrified face. The squad leader hesitates. They have no clear orders on handling prisoners. The brutality of war demands one thing; shared blood demands another. After a long, silent beat, Captain Lee's voice cuts through from outside, calling them back to their overall objective. The film strongly implies the squad spares the prisoners, including Young-bok's cousin, as they move on--an outcome where potential atrocity is averted by a personal connection, but the emotional scar remains.

Back at the American headquarters, Maggie relentlessly chases the story of the Jangsari operation. She corners staff officers, pieces together radio intercepts, and finally slips into a briefing room where she overhears enough to understand the truth: the Independent 1st Guerrilla Battalion is being "written off" in planning documents. Resupply is not scheduled. Extraction is "unlikely." The operation is explicitly described as a diversion whose participants are not expected to survive.

She confronts Stevens again, her voice low but shaking with fury. "You're sacrificing them. You're not even planning to get them out."

He doesn't deny it this time. "If Jangsari draws enough attention, Incheon succeeds. If Incheon succeeds, the entire peninsula could be saved," he argues, almost pleading with himself as much as with her. "The mission at Jangsari could save hundreds of thousands."

"At the cost of 772 boys who barely know how to hold a rifle," she replies. "Do their lives count for nothing because they're Korean? Because they're poor? Because they're students and not professionals?"

Stevens is caught between conscience and duty. "We don't have ships to spare," he says. "We don't have air assets to devote to a retrieval. I've been told to maintain operational secrecy. If this gets out, MacArthur's entire plan is at risk."

"Let me report it," she urges. "Let the world see what you're doing. Maybe then someone--anyone--will act."

He hesitates again, then shakes his head. "No, Ms. Miller. I can't authorize that."

But her anger only hardens into determination. She begins drafting unsanctioned dispatches, pushing them through unofficial channels, trying to reach editors back home who might dare to print them despite censorship. Megan Fox's portrayal is of a reporter with an uncompromising moral core, an amalgam of real correspondents who fought to expose injustices during the war.

As day turns to night and back again at Jangsari, the boys dig in. They fortify trenches and seize what weapons and rations they can from the captured North Korean base. Food is scarce--their own supplies were light, and enemy stockpiles are small. Cans of rations are shared three to a tin. A boy licks the inside of an empty can, embarrassed when another sees him.

They try to rest in the shallow safety of slit trenches. Rain begins drifting in. Somewhere inland, artillery rumbles--distant but ominous.

In one quiet scene, Choi Sung-pil sits alone on a cliff overlooking the dark sea, the distant shape of their transport ship having vanished hours before. The sky is iron-grey; waves pound the rocks below. He holds a small object--a keepsake from home, perhaps a folded photo or talisman. He finally opens up to a fellow student, revealing his past.

"I'm not from the South," he admits, voice low. "I was born in the North. My family moved down when I was young."

The other boy looks at him in surprise. "So why fight? Why risk your life here?"

Sung-pil's eyes are distant, haunted. In a later monologue, he explains that his family fled North Korea after political violence; someone they loved was branded an enemy, perhaps executed, forcing them south. The ideological purity of either side doesn't matter to him anymore. "I joined because… if someone has to die for this land, for our families, maybe it should be me. At least I chose it." His confession is one of the film's most moving scenes, underscoring the theme that North and South Koreans are intertwined, often victims of forces far beyond their control.

The boys share their reasons for joining: revenge for family members killed by Northern forces; desire to prove themselves; simple patriotism; or, like Ki Ha-ryun, a naive hunger for adventure and glory that now feels grotesquely misplaced.

That night, under a sky slit by distant flares, a North Korean counterattack probes their lines. Small units attempt to retake the high ground overlooking the beach. In intense, close‑quarters fighting in trenches, boys from both sides grapple in the mud, stabbing, shooting at point‑blank range. Several student soldiers die here: one is bayoneted as he scrambles to reload; another is shot in the neck, clutching at the wound as his friend tries to stop the bleeding, failing as blood seeps through his fingers. North Korean attackers fall in equal number, some rolling down the sandy slope, lifeless.

The students repel this initial counterattack, but at heavy cost. The wounded moan through the night. A makeshift aid station is set up in a bunker; a barely‑trained medic tries to stitch a torn abdomen with shaking hands. Some boys bleed out because there is simply no morphine, no blood, no surgeons.

At dawn on September 15, 1950, word filters through broken radio bursts and rumors: MacArthur's landing at Incheon is underway. The diversion at Jangsari has helped; North Korean attention has been split. But for the boys on this beach, that strategic success brings no immediate relief.

By now, the last functioning radio set has broken down completely--damaged in shelling, or overloaded by their frantic attempts to call for help. Fuel canisters sit empty. Ammunition crates are half‑open and nearly spent. Their original mission--to stage hit‑and‑run attacks against supply lines--has dwindled into a simple struggle to stay alive.

From a high vantage point, a lookout spots movement along a ridge road: a larger North Korean force is approaching, trucks and infantry, prepared to retake Jangsari in force now that they have realized the scale of the incursion. Dust trails mark their advance.

In the command dugout, Captain Lee studies a rough map lit by a flickering lantern. Student squad leaders crowd around--Choi Sung-pil, Ki Ha-ryun, and others. The mood is grim.

"We have almost no ammunition. Food will last maybe another day, if that," one NCO reports.

"And no radio," another adds. "We can't call for extraction, we can't call for artillery, we can't even confirm that Incheon has succeeded."

Captain Lee lights another cigarette, his hands steady by force of will alone. "If they encircle us, it's over. We'll be wiped out."

"What are we going to do, sir?" Sung-pil asks, eyes hard but voice betraying his age.

Lee looks up. "We hit them first."

There's a murmur of disbelief. "Sir, they outnumber us…"

"We're dead if we stay. The only chance is to surprise them, take out their lead elements, and capture a working radio from their communications unit," he says. "If we get that radio, maybe--just maybe--we can call someone, anyone, to get us out."

It is a suicidal plan, but there is no better option. The boys nod, because they have passed beyond fear into a kind of numb resignation. When you've watched your friends die on the sand beside you, charging an enemy column seems almost logical.

As they prepare for this surprise attack on the approaching North Korean troops, Maggie in the US headquarters is waging her own battle. She has managed to get General Stevens alone, away from staff and stenographers.

"You know what's happening at Jangsari right now," she says. "Those boys are out there with no support, no resupply, no way out. You can at least send a ship. A few planes. Something."

Stevens rubs his temples. "I've petitioned for a diversionary destroyer, a recon flight. My requests were denied. Incheon is consuming everything. Every plane, every ship, every ounce of political cover."

"Then break the rules. You're a general. You have authority."

"I have a chain of command," he counters. "If I divert assets without authorization, I risk the entire operation. MacArthur will--"

"MacArthur isn't standing on that beach," she cuts in. "Those boys are."

There's a long pause. He stares at his hands. "I will… try again," he says finally. "But I can't promise anything."

It is as much as he can bring himself to offer. The film makes clear that while American command under MacArthur is willing to let the students walk into a trap for strategic advantage, Stevens is not portrayed as an outright villain but as a man trapped in a ruthless calculus.

Back on the Jangsari hills, the students move into position. The light is leaden, the air heavy with the scent of wet earth and spent explosives. They creep through gullies and along ridgelines, flanking the road where the North Korean reinforcements will pass. Captain Lee divides them into small fire teams, assigning lanes of fire.

"You see their radio truck, you take it," he instructs. "We need that radio. Focus on that."

They wait in silence, breaths shallow, fingers on triggers. Ki Ha-ryun mutters, "When this is over, I'll go back and find those girls who wrote me." Sung-pil glances at him, a faint, sad smile. "You better," he says. "They'll be angry if you don't."

The North Korean column appears: trucks loaded with infantry, a small armored car, and in the middle, a vehicle bristling with antennae--their field communications unit. The driver smokes casually, unaware of eyes tracking him from the hills.

Captain Lee raises his hand, holds it a beat, then drops it.

The hillside erupts.

Rifles and captured machine guns snap, muzzle flashes ripping into the lead truck. The driver slumps over the wheel, the vehicle careens off the road, smashing into a ditch. North Korean soldiers tumble from the back, some dead, some scrambling for cover. Grenades arc from the students' positions, detonating in the middle of the column, tearing apart men and metal alike.

Several North Korean soldiers die instantly in the first volley--drivers, radio operators, infantrymen--cut down before they can even shoulder their weapons. Others, wounded, crawl toward ditches, only to be finished by precise shots as the students press their advantage.

But the North Koreans are not helpless. Their rear guard reacts quickly, swinging machine guns toward the ridge lines. Bursts of fire stitch across the hillside. A student to Sung-pil's left jerks backward, a red spray from his chest, and rolls down the slope, dead. Another is hit in the leg, screaming, and is dragged to cover by his comrades.

Ki Ha-ryun stands to throw another grenade, shouting, "For--!" The words are swallowed as a bullet punches through his helmet. He drops as if the strings have been cut, grenade falling from his fingers. A squad mate dives, grabs the grenade, and hurls it at the last moment--killing two more North Korean soldiers when it detonates beside their firing position. Ki Ha-ryun lies still, eyes wide to the sky, his dreams of letters and girls ending on a nameless hillside.

Captain Lee personally leads a small team in a downhill charge at the communications truck, firing as he runs. Two North Korean radio operators fire back from behind the vehicle; one is hit in the throat and crumples, the other tries to flee and is shot in the back by a student rifleman, collapsing beside the road. A third lunges from the passenger side with a pistol; Lee grabs his wrist, struggles, and drives a knife into his ribs. The man gasps, clutches at the wound, and dies at Lee's feet.

They seize the truck. Inside, the radio set is intact. One of the older NCOs jumps in, frantically trying to tune it to allied frequencies. Around them, the firefight rages. Students and North Korean troops trade fire among smoking vehicles and dead bodies. The air is filled with the crack of rifles, the thud of impact, the screams of the wounded.

More student soldiers die here: one takes a burst in the back while dragging a wounded friend; another, ducking behind a wheel well, is killed when a bullet ricochets under the truck. Several North Korean infantrymen are killed as they attempt to climb the slope, one tumbling back with a bayonet lodged in his ribs, another falling from a grenade's blast that shreds his legs.

At last, the NCO shouts, "Signal! I have a signal!" They manage to send a desperate, crackling transmission--identifying themselves as the Independent 1st Guerrilla Battalion at Jangsari, under heavy attack, requesting immediate extraction or support. They have no way of knowing if anyone hears.

They manage to scatter the North Korean column, destroying vehicles and killing many of the attackers. The survivors withdraw, regrouping out of range. The students limp back to their hill positions, hauling the heavy radio components with them. It is a tactical victory--but a Pyrrhic one. Their numbers have dwindled further. The victory buys time, not salvation.

At headquarters, a signal operator rushes into Stevens's office. "Sir, we just got a fragmented transmission from Jangsari. It's them. They're still alive. They're under attack, requesting extraction."

Stevens grips the edge of his desk. "Can we respond?"

"Signal is weak, sir. Fading in and out. We might get a short message through."

"Send: 'Message received. Stand by.'" He pauses. "And get me the Navy liaison. Now."

Maggie watches from the doorway as he fights his own chain of command yet again, arguing for even a token rescue: a destroyer to steam close enough to shell North Korean positions, a transport to pick up survivors. The answer, from above, remains essentially the same: No assets available. Maintain focus on Incheon. Jangsari is expendable.

"You heard their voices," she tells Stevens after the call ends. "You heard them calling for help."

He looks older now, deeply tired. "I did," he says softly. "And I don't know if help is going to come."

Back at Jangsari, time devours their hope. Ammunition runs lower and lower. The boys count their remaining rounds, trading, sharing. A handful of bullets weighs more than gold. Food is almost gone. Some tear up old letters and notes, unwilling to leave recognizable names on enemy-held ground.

Throughout September 15, North Korean forces continue to probe and attack. Each clash costs lives on both sides. The students repel one assault only to have another begin. They fight off North Korea's counterattacks until they are completely out of ammunition. One by one, rifles click empty. Boys who only days ago sat joking on a transport ship now stare at useless weapons, hands shaking.

In a final, harrowing engagement, North Korean troops push hard on their flanks. The students fall back toward the beach, dragging wounded comrades, leaving behind hastily dug positions. Several more die in this withdrawal, shot while covering their friends or cut down by unseen snipers. One student, out of bullets, charges with his bayonet and is mowed down. Another uses his last grenade to halt a group of pursuing North Koreans, killing them at the cost of his own life when he is exposed by the throw.

Captain Lee, battered, bleeding from a shrapnel wound in his shoulder, orders a general withdrawal toward the shore. His voice cracks as he shouts over explosions, "Back to the beach! Move! Don't stop!"

There is no dramatic rescue ship waiting, no cavalry of planes dropping ladders from the sky. There is only the grey expanse of sea, and the knowledge that they must somehow slip away under fire. They begin to withdraw under fire, using what little cover remains, some wading back into the same water that was choked with bodies when they arrived.

On the sand, more boys fall. A bullet catches one in the head as he runs, his body crumpling and sliding into the surf, the tide beginning to pull him away. Another, helping a limping friend, is hit--he shoves his comrade onward and collapses, face in the sand, unmoving. Each death is quick, brutal, often anonymous. The film does not catalogue every name, but it insists that every loss is felt.

By the time the remnants of the Independent 1st Guerrilla Battalion finally pull themselves away from Jangsari--some by small craft, some by stealing local boats, some perhaps slipping down the coast under cover of darkness--139 of them have been killed in action. Between the landing, the counterattacks, the surprise assault on the column, and the final withdrawal, those 139 deaths come from North Korean bullets, grenades, and artillery--from the merciless machinery of a war that saw them as pawns.

We do not see each individual boy's final breath, but the film emphasizes the cumulative weight of their sacrifice. For every face still present at the end, several are missing--ghosts recalled in quick flashes, in empty bunk spaces, in discarded helmets on the shore.

Back in Seoul, or perhaps at another rear base, the survivors stand in loose, stunned formation. Uniforms torn, bandages bloodstained, eyes hollow. Choi Sung-pil is among them--alive, though scarred in ways deeper than the scratches on his skin. Captain Lee stands before them, his own uniform singed and stained. He reads off casualty figures, his voice barely more than a rasp. "KIA… 139," he says. The number hangs in the air like smoke.

One boy, whose best friend died in the water on that first day, stares straight ahead, tears streaming silently down his face. Another grips his helmet so hard his knuckles blanch. Ki Ha-ryun's absence feels particularly sharp; the film may briefly show the letter he never got to send, or the names of the girls he had boasted about, now meaningless.

In an office half a world away, Maggie files her report on Jangsari: Forgotten Heroes. She has gathered names, photos, testimonies from the few survivors she can reach. She writes about children sent into a diversionary landing with inadequate training, equipment, food, and support, about how they were meant to draw fire so others could win glory elsewhere. Her piece fights against censorship, but whether it reaches the broader world or not, the film suggests that her efforts are a form of moral acknowledgment, a refusal to let their story vanish.

She meets Stevens one last time. He reads her draft, his jaw clenched. "History will remember Incheon," he says quietly. "I don't know if it will remember Jangsari."

"Then we'll remind it," she replies. "Over and over, until it can't look away."

He nods once, the gesture of a man who knows he has failed these boys in some ways, even if the broader war was advanced by their sacrifice. The portrayal of Americans is not purely heroic; under MacArthur's strategy, they accepted the possibility that none of the students would survive, and that moral compromise is laid bare.

In the film's final scenes, the camera returns to Jangsari Beach. The tide has washed away many of the physical traces of battle. The sand is smooth where boys bled and died. Only a few rusting shell casings and broken planks remain. The sea rolls in and out, indifferent.

Overlayed, or perhaps on screen, a dedication appears to the 772 student soldiers of the Independent 1st Guerrilla Battalion, acknowledging that most of them were teenagers given almost no training, thrown into a mission that official histories largely ignored. The film underscores that their diversion contributed to the success of the Incheon Landing, which in turn helped reverse the course of the war--but that their names, their stories, and their suffering went mostly unrecognized for decades.

We see Choi Sung-pil again, maybe older, or maybe simply changed, standing somewhere quiet--on a train platform, in a schoolyard, or on another beach--carrying within him the memory of every face left on Jangsari's sand. He stares toward the horizon as if seeing the guns, the ropes, the rising sun on that fatal morning.

There is no triumphant music. No swelling flags. The last mood is sombre, almost unbearably so. The war continues offscreen, massive operations like Incheon dominating textbooks, but the film's gaze stays with the young men who fought, killed, and died as a diversion.

The final feeling is clear: this was a victory paid for with children's lives, and the world took far too long to say their names.

What is the ending?

In the ending of "Battle of Jangsari," the young soldiers, after enduring heavy losses and facing overwhelming odds, manage to complete their mission. They successfully create a diversion for the main forces, allowing the larger operation to proceed. However, many of the soldiers do not survive the battle. The film concludes with a somber reflection on the sacrifices made, highlighting the bravery and determination of the young men who fought.

As the final scenes unfold, the tension is palpable. The young soldiers, who have been thrust into the chaos of war, are preparing for the climactic battle at Jangsari. The atmosphere is thick with anxiety and fear, yet there is also a sense of camaraderie among them. They are aware that their mission is crucial for the success of the larger operation, and this knowledge weighs heavily on their shoulders.

The battle begins with the sound of gunfire and explosions echoing in the distance. The soldiers, many of whom are barely out of their teens, are filled with a mix of dread and determination. They charge into the fray, their faces a mixture of fear and resolve. As they engage the enemy, the chaos of war envelops them. The camera captures the frantic movements, the shouts of commands, and the cries of the wounded, immersing the audience in the harrowing reality of battle.

As the fight intensifies, the characters are pushed to their limits. One of the main characters, a young soldier named Kim, shows remarkable bravery, rallying his comrades even as they face overwhelming odds. His internal struggle is evident; he grapples with the fear of death but is driven by a desire to protect his friends and fulfill their mission. The emotional weight of his decisions is palpable as he witnesses the loss of his fellow soldiers.

Throughout the battle, the soldiers face numerous challenges. They encounter heavy enemy fire, and the toll of the conflict becomes increasingly apparent. The camera lingers on the faces of the soldiers, capturing their fear, determination, and moments of despair. As they push forward, they lose many of their comrades, each loss hitting them hard and deepening their resolve to honor their fallen friends.

In a pivotal moment, Kim and a few remaining soldiers manage to execute a critical maneuver that creates the diversion needed for the main forces to advance. This moment is filled with tension as they risk everything, knowing that their lives hang in the balance. The success of their mission is bittersweet, as they realize that their sacrifices may not be in vain, but at a tremendous cost.

As the battle winds down, the surviving soldiers are left to grapple with the aftermath. The scene shifts to a somber reflection on the battlefield, where the weight of their losses hangs heavy in the air. The camera captures the devastation around them, the fallen soldiers, and the remnants of the fierce fight. Kim, now a changed man, stands amidst the ruins, reflecting on the cost of war and the bravery of his comrades.

In the final moments, the film emphasizes the theme of sacrifice and the harsh realities of war. The surviving soldiers are seen walking away from the battlefield, their faces etched with grief and determination. They carry the memories of their fallen friends with them, a poignant reminder of the price of their mission. The film closes on a note of somber reflection, leaving the audience to ponder the bravery and sacrifices made by these young men in the face of overwhelming adversity.

Is there a post-credit scene?

The movie "Battle of Jangsari," produced in 2019, does not have a post-credit scene. The film concludes its narrative without any additional scenes or content after the credits roll. The focus remains on the intense and emotional story of the young soldiers involved in the battle, emphasizing their bravery and sacrifices during the Korean War. The ending serves to encapsulate the themes of heroism and the harsh realities of war, leaving the audience with a poignant reflection on the events depicted in the film.

What role does the character of Kim Il-woo play in the Battle of Jangsari?

Kim Il-woo is a key character in the film, portrayed as a young soldier who is initially inexperienced and fearful. Throughout the story, he undergoes significant character development, evolving from a hesitant recruit into a courageous fighter. His internal struggles and growth are highlighted during the intense battle scenes, where he learns to confront his fears and take on leadership responsibilities.

How does the film depict the relationship between the soldiers and their commanding officers?

The relationship between the soldiers and their commanding officers is depicted as complex and often strained. The soldiers, many of whom are young and inexperienced, feel a mix of fear and respect towards their commanders. This dynamic is particularly evident in scenes where orders are given under pressure, showcasing the tension between the desire to follow orders and the instinct for self-preservation. The commanding officers, while authoritative, also show moments of vulnerability, revealing their own fears and the weight of their responsibilities.

What is the significance of the Jangsari beach setting in the film?

The Jangsari beach setting is significant as it serves as the backdrop for the pivotal battle in the film. The beach is depicted as a harsh and unforgiving environment, symbolizing the chaos and brutality of war. The cinematography captures the desolate beauty of the landscape, contrasting with the violence that unfolds. The setting also plays a crucial role in the strategic planning of the battle, as the soldiers must navigate the challenges posed by the terrain while executing their mission.

How does the film portray the theme of sacrifice among the soldiers?

The theme of sacrifice is portrayed through the actions and decisions of the soldiers during the battle. Several characters are faced with life-and-death choices, highlighting their willingness to put their lives on the line for their comrades and the greater cause. Emotional scenes depict the camaraderie among the soldiers, as they support each other in moments of despair and fear. The film emphasizes the personal sacrifices made by these young men, showcasing their bravery and the heavy toll of war.

What internal conflicts does the character of Lee Joon-seok experience throughout the film?

Lee Joon-seok, a central character, experiences significant internal conflict as he grapples with the realities of war and his responsibilities as a leader. Initially filled with doubt and fear, he struggles to maintain morale among his troops while facing the harsh consequences of battle. His journey is marked by moments of self-reflection, where he questions his decisions and the cost of war, ultimately leading to a deeper understanding of courage and sacrifice.

Is this family friendly?

"Battle of Jangsari," produced in 2019, is a war film that depicts the events surrounding the Korean War, specifically focusing on the Battle of Jangsari. While the film aims to portray the bravery and sacrifice of soldiers, it contains several elements that may not be suitable for children or sensitive viewers.

-

Graphic Violence: The film includes intense battle scenes with gunfire, explosions, and injuries, which can be quite graphic and may be distressing for younger audiences.

-

Death and Loss: Characters experience significant loss, and there are scenes depicting the death of soldiers, which can evoke strong emotional reactions.

-

War Trauma: The psychological impact of war is explored, showcasing the fear, anxiety, and trauma faced by the soldiers, which may be unsettling for some viewers.

-

Mature Themes: The film addresses themes of sacrifice, duty, and the harsh realities of war, which may be difficult for younger viewers to fully comprehend.

-

Emotional Distress: Characters undergo intense emotional struggles, including moments of despair and hopelessness, which could be upsetting for sensitive individuals.

Overall, while "Battle of Jangsari" is a significant historical narrative, its content may not be appropriate for all audiences, particularly children or those who are sensitive to depictions of violence and emotional turmoil.