Ask Your Own Question

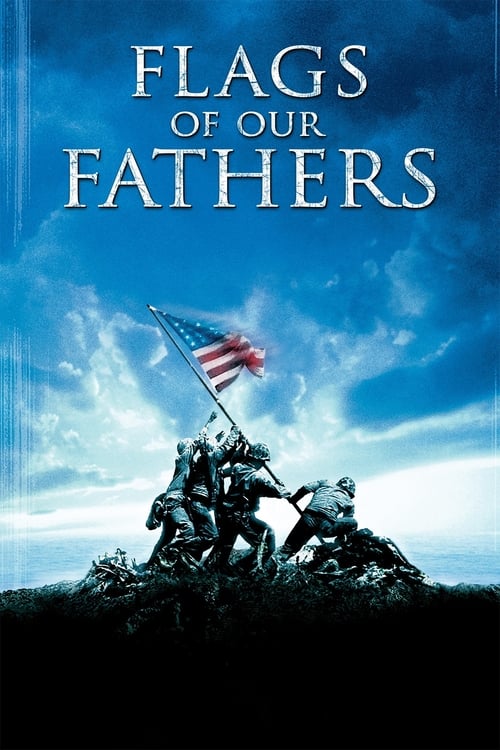

What is the plot?

In darkness broken by the hiss of surf and the thrum of engines, an armada pushes toward a black shape on the horizon. It is February 1945, the Pacific night cold and heavy. Aboard one of the ships, young men try to sleep or pretend to. Others smoke, write letters, or stare out at the water, listening to the distant, relentless boom of naval guns softening Iwo Jima before dawn.

Among them is Pharmacist's Mate Second Class John "Doc" Bradley, quiet, watchful, a Navy corpsman attached to the Marines. Nearby, Corporal Harlon Block from Texas jokes with his friend Private First Class Franklin Sousley, lanky and boyish. Sergeant Michael "Mike" Strank, their respected squad leader, moves easily among his men, calm as if he's done this a hundred times. Sergeant Hank Hansen, cocky and sure of himself, polishes his weapon by rote. Private First Class Ralph "Iggy" Ignatowski fumbles with a photograph from home. Off to one side, Private First Class Rene Gagnon, a young New England runner turned message runner, nervously folds and refolds a cigarette pack. And standing just beyond them, a Pima Native American Marine, Private First Class Ira Hayes, watches silently, his dark eyes reflecting gunflashes on the horizon.

Decades later--and suddenly, simultaneously--it is 1994. An old man gasps for breath in a dim hospital room. Tubes run from his arms, machines mutter and beep. This is Doc Bradley at the end of his life, his hair white, his face creased by years of things never spoken aloud. His adult son, James Bradley, sits close, pen and pad ready, because his father has finally agreed to talk. The old man's eyes are distant, fixed on something only he can see.

"Did I ever tell you…about Iwo?" John Bradley murmurs.

The room fades. The war comes back.

On the morning of 19 February 1945, the black sands of Iwo Jima appear through smoke and haze as the Marines of the 28th Marine Regiment, 5th Marine Division slam ashore under a deafening barrage. The volcanic sand gives way under their boots, sucking at their legs. Mortar rounds walk along the beach. Men vanish in bursts of sand and blood. Corpses already litter the tide line as the waves roll in and out, pink-tinged.

Doc throws himself into the chaos, his white armband a small, useless target. He crawls from man to man, hands slick with blood, shouting, "You're okay, you're okay! Stay with me!" even when he knows they are not. Above the beach, dark openings in the rock spit machine-gun fire. The island is honeycombed with caves; few Japanese are visible, but they are everywhere.

In another time entirely--but intertwined with this one--the roar of an American crowd drowns out the memory of that surf. Bright stadium lights blaze down on a fake papier-mâché mountain in the middle of Soldier Field in Chicago, fireworks exploding overhead. Three men in dress uniforms, tiny against the spectacle around them, climb the artificial slope with a long pole wrapped in cloth. Doc Bradley, Rene Gagnon, and Ira Hayes reenact the moment they have been told made them "heroes," trying to plant a replica flag as the crowd screams.

As flashes of light from the fireworks strobe across their faces, each man is dragged back in his mind to the other mountain, the real one: Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima.

Training flashes by, the months before the landing: Camp Tarawa in Hawaii, where the 28th Marines run themselves to exhaustion, hauling logs, crawling under barbed wire, learning the shape of Iwo Jima from maps and sand tables. Mike Strank's squad bonds in the narrow spaces between fatigue and drills. He is their anchor: calm, practical, stern when needed, but always fair. He tells them quietly, "I'll get you home to your mamas," a promise he believes as he says it.

Ira, soft-spoken, keeps his worries to himself. He drinks when he can--still controlled, not yet the desperate thing it will become--and shares dark jokes with Franklin and Iggy. Rene chatters about life after the war, the jobs he might get, the girls he'll impress. Harlon thinks of Texas and the flat, open fields where his family lives. Doc, not quite like the Marines around him, knows his job is not to kill but to keep them alive, and the pressure sits heavy on his chest.

Back in 1994, James Bradley pores over photographs and letters, interviewing old men who once were young Marines. The film's narrative moves through his research as voiceover: he is trying to find the truth about his father and about the famous photograph that came to define the Battle of Iwo Jima. The story refuses to stay in one place; it keeps looping back, pulling the viewer through battle, fame, and aftermath.

On Iwo Jima's black beach, time slows and stretches again. The first days are pure survival. The Marines claw inch by inch up from the beach toward the interior, pinned down by artillery from the heights. The objective is clear: take Mount Suribachi, the volcanic peak dominating the southern end of the island, because as long as the Japanese hold it, the beaches are deathtraps.

The 28th Marines finally fight their way to the lower slopes. The mountain's sides are sheer, pitted with caves. The air smells of sulfur and cordite. Japanese machine guns rake the approaches, mortars burst overhead, and everything is coated in black ash that turns instantly to mud with blood and rain. Men fall and are left where they lie. There is no time, no space to grieve.

On an early morning, a patrol led by Lieutenant Harold Schrier pushes up toward Suribachi's summit with a small flag and a length of pipe. Among the Marines who secure the path are elements of Mike Strank's squad, though they are not the ones chosen to lift the first flag. In the fog and smoke at the crater's edge, the first American flag is raised over Mount Suribachi. Down below on the beach and the ships, thousands of men cheer, ships' whistles blaring. For a moment, hope surges through the exhausted Marines.

Back at the base of the mountain, though, the moment passes quickly. Firing continues. The battle is far from over.

Later that day, orders come down: the first flag is too small; a larger one is wanted, one that can be clearly seen from the ships. It needs to go up, and the first one must come down. The task falls to a small group of Marines and their corpsman. This time, it will be Mike Strank's boys.

So it is that, on the afternoon of 23 February 1945, Mike Strank, Harlon Block, Franklin Sousley, Ira Hayes, and others including Private First Class Harold Schultz and Corporal Harold Keller (men whose correct identities will only be fully recognized decades later, beyond the film's own claims), climb toward the top of Suribachi with a long piece of pipe and a fresh flag. With them as runner is Rene Gagnon, carrying messages and the flag itself.

On the rim, as men cluster near a shallow crater and the wind whips at their clothes, Joe Rosenthal of the Associated Press raises his camera, not knowing exactly what he will capture. The Marines begin to hoist the flagstaff. In the film's telling, the six visible men are Sergeant Mike Strank, Corporal Harlon Block, Private First Class Franklin Sousley, Sergeant Hank Hansen, Rene Gagnon, and Doc Bradley. As they plant the base of the pipe into the rocky soil and push together, shoulders straining, the shutter clicks.

The second flag rises over Iwo Jima.

Nobody on the summit realizes this fraction of a second will become one of the most reproduced photographs in history. They cheer, pose for other, more deliberate photos, joke about going home. Down below, some men see the flag go up again and shout. But for the Marines on the mountain, the battle continues. The Japanese on the northern two-thirds of the island fight on for five more brutal weeks.

In Washington, DC, though, that image will soon appear in newspapers and on front pages. It will be taken as a symbol of victory, even though the island is still a killing ground. And it will change the lives of the men in it forever.

On Iwo Jima, days blur. The flag raising is just one moment wedged among thousands of other moments: artillery bursts, screams for corpsmen, the metallic stink of blood. Mike Strank keeps his men moving, using every scrap of cover he can find. He is the one they look to, the one whose decisions mean life or death. He is also the first among the core group to die.

One day, as they advance over broken ground under cover of their own supporting fire, a U.S. Navy shell falls short. The explosion slams into Mike's position. When the dust clears, he is down, grievously wounded. The irony is brutal: after surviving Japanese fire, he is killed by American artillery. Doc scrambles to him, hands desperate, but it is no use. Mike Strank dies from his wounds, killed by friendly Navy shellfire.

His death cracks something in the squad. The man who promised to get them home will never leave the island.

Later that same day, death stalks closer still. Sergeant Hank Hansen, moving up in the line of advance, is suddenly hit in the chest by enemy fire. He drops almost immediately, a dark red bloom spreading across his uniform. He is dead in an instant, killed by a Japanese bullet to the chest. There is no time to linger over his body. The squad pushes on, numb, smaller each hour.

Harlon Block steps into the space that Mike left, helping lead his friends forward. The fighting slides into a pattern of advance, dig in, face counterattack, repeat. Near networked cave systems, the Japanese pop up from hidden exits and fire at point-blank range, then vanish again. One day--as dates begin to blur even for the men themselves, though the film ties Franklin's death to 21 March 1945--Harlon moves ahead under withering machine-gun fire. In a burst of tracer and tearing sound, he jerks and goes down. He has been cut down by Japanese machine-gun fire, dying there on the torn ground, just weeks after his hands helped raise the flag.

Now, of the original flag-raising core, more are dead than alive. The camera--and Doc Bradley's memory--lingers on Harlon's still form. Somewhere back in Texas, his family does not yet know what has happened.

As the days grind on, the squad's world shrinks to a few yards of terrain at a time. One night, in the constant eerie darkness broken by flares, Doc works on a wounded Marine, hands deep in torn flesh while bullets crack overhead. Beside him, Ralph "Iggy" Ignatowski offers cover, nervously watching the shadows. Then, in a flash of movement, Japanese soldiers burst out from a tunnel entrance behind them. Before Doc can shout, they seize Iggy, clubbing him and dragging him toward a black hole in the rock.

"Iggy!" Doc screams, scrambling after them, but gunfire forces him down. Grenades explode. By the time he can move forward, Iggy is gone, swallowed by the tunnels.

For two long days, the squad can do nothing but imagine what is happening to their friend underground. At last, doc and others clear a cave complex and find him. Iggy's body lies twisted in the shadows, mutilated beyond easy recognition, his face and limbs savaged by torture. The camera does not show everything, but Doc's expression tells the story. The Japanese troops who captured him have killed him in the darkness after unspeakable abuse. Iggy is beyond help, beyond pain. Doc kneels beside him, stricken. As corpsman, he feels every death as a failure, but this one claws especially deep.

The names of living comrades are fewer now. Only Doc Bradley, Ira Hayes, Franklin Sousley, and Rene Gagnon remain from the small group the film follows most closely. They move together, an ever-decreasing knot, under a sky that seems always filled with smoke.

On 21 March 1945, in another push across unforgiving ground, Franklin runs beside Ira. They are exposed, sprinting past a shallow depression, when a burst of Japanese machine-gun fire rips across their path. Franklin staggers, the rounds cutting into him. He collapses, bleeding heavily. Ira dives to him, trying to drag him to cover, shouting his name.

"Frankie! Frankie, stay with me!"

But the damage is too great. Franklin Sousley dies there in Ira's arms, killed by machine-gun rounds. Ira clutches his body, yelling in rage and grief, his voice raw, until other Marines pull him away. The war moves on even as his friend's life ends.

Of the eight original men in Mike Strank's squad that the film has shown us, only three are left: Doc, Ira, and Rene. The island is nearly secured, but the cost has been obscene. Iwo Jima will become known as one of the bloodiest battles of the war, a 36-day struggle in which thousands die on both sides. For the survivors, the ground is haunted by ghosts.

A few days after Franklin's death, while still on Iwo, Doc runs forward through incoming fire to reach another wounded corpsman. He has done this dozens, hundreds of times, but this time a Japanese artillery round impacts nearby. The blast sends him flying. He hits the ground hard, his leg torn open, shrapnel embedded deep. As his vision warps and narrows, he tries to crawl, but other Marines grab him, drag him back. His war on Iwo Jima ends there, in a haze of pain and morphine, as he is evacuated, his work unfinished.

Ira and Rene remain on the island as mop-up continues, but soon the machinery of public relations catches up with them. That photograph--Rosenthal's image of six men lifting the flag--has already raced across the United States. The nation, weary of casualty lists and rationing, clings to it as a symbol of hope. The Treasury Department sees it as a lifeline: a rallying cry for the Seventh War Loan bond drive.

Back in American offices, Bud Gerber of the Treasury Department studies the picture. His task is clear: find the flag raisers, bring them home, and put them in front of crowds until enough war bonds are sold to keep the war machine running. Identifications are made quickly, too quickly. Some names are guessed or accepted without careful verification. Initially, the Marine Corps believes the visible Marines include Sergeant Hank Hansen and not Harlon Block. That error will haunt everyone.

On Iwo, a photographer and officers approach Gagnon, Ira, and the wounded Doc with news: they are in the photograph; they are "heroes." Rene, who has longed to go home, sees a chance. Ira is resistant, uncomfortable with the attention and the idea of being singled out. Doc, still stunned and in pain, barely processes what is happening.

In a tent, with the flag photo spread out, Rene and Ira argue. The official story says that the three identified Marines in the image are Doc, Rene, and Hank Hansen. But privately, Rene has doubts. Another pressing question emerges: who is the sixth man in the photograph?

One night, with rain drumming on canvas, Rene turns to Ira. "I think you're the sixth guy," he says, pointing to the blurred figure at the far end of the flagstaff.

Ira stiffens instantly, eyes blazing. "It wasn't me," he snaps. "It was Harlon in that picture. Not me."

Rene presses. "Look, if it's you, if we say it's you, they'll send us home. Don't you want to get off this rock? We can be done. All we gotta do is say it's you."

In a heartbeat, the mood changes from tense to deadly. Ira grabs his bayonet and lunges, pinning Rene back, the blade pressed against his throat. His voice is low, furious.

"You say that again, I'll kill you. You tell them it's me, I swear to God I'll kill you."

Rene freezes, feeling the cold steel and the bigger, deeper fear in Ira's face. He backs off, shaken. For now, he does not name Ira as the sixth man. The truth of Harlon's presence in the photograph, however, will be buried under expedience and confusion for years.

The three identified survivors--Doc Bradley, Rene Gagnon, and Ira Hayes--are pulled from combat and shipped back to the United States. When they arrive in Washington, DC, the war is still raging across the Pacific, but here there are banners, flags, and brass bands. The men step off trains to a "hero's welcome," crowds cheering, cameras flashing. A motorcade carries them past the Capitol, the White House, and monuments. They are ushered into fine rooms, given clean uniforms, plied with food and drink.

Doc, uncomfortable in dress blues, scans a sheet of paper with the names of "gold star mothers" invited to meet them. He notices something odd: the list includes Harlon Block's mother? It doesn't. Instead, it mentions Hank Hansen's mother--and yet Doc is increasingly certain that Hansen was not on the base of the flag in the famous photo, and that Harlon was. But the machine is already in motion. Admitting the mistake would cause embarrassment, confusion, maybe jeopardize the bond drive.

Their Treasury handler, Bud Gerber, makes it clear how high the stakes are. When Ira, shaken and angry, calls the bond drive a "farce," saying the whole spectacle feels false, Gerber snaps. In a private meeting, his tone turns harsh.

"If this bond drive doesn't work," Gerber tells them, "we don't have the money to keep fighting. If it fails, we abandon the Pacific. We leave your buddies to die for nothing."

The words hit like a blow. The implication is stark: shut up, play along, or your friends still in combat will be sacrificed. Under that pressure, the three men agree to maintain the official story, not to contradict the identification of Hank Hansen as one of the flag raisers, and not to reveal that he was not actually in the photograph. Hank is already dead; the dead cannot correct the living.

So the tour begins. City after city, stadium after stadium, they stand on stages under spotlights, repeating the same lines about courage and sacrifice, urging Americans to buy war bonds. They are paraded past towering mock-ups of the photograph, asked to sign copies, to reenact their deed.

In that spectacular night at Soldier Field in Chicago, the reenactment on the fake mountain becomes a grotesque echo of the real thing. As Doc, Rene, and Ira climb the papier-mâché slope, fireworks thunder overhead, red, white, and blue explosions bathing them in flashing light. The crowd sees a stirring patriotic show. The men see something else.

As Doc reaches the top, his mind rips back to the jagged rim of Suribachi, to Mike's easy smile before the shell hit, to Harlon's collapse under machine-gun fire, to Iggy's broken body in the cave. The roar of fireworks blends with the roar of artillery. Below, the Chicago crowd chants. On Iwo, men screamed for corpsmen. Time folds in on itself.

Rene, who has always liked being noticed, leans into the attention. He smiles for the cameras, works the press, lets his girlfriend revel in the limelight. He collects business cards and promises of jobs after the war. He believes this is his ticket to success, that being "the guy from the picture" will open doors forever.

Ira, by contrast, is unraveling. Each appearance tightens the vise on his conscience. He knows the official story is wrong. He knows Harlon's parents think their son is not in the famous image that the whole country is worshipping. He hates being called a hero for something he considers a fluke, a random instant in a long, dirty battle where real heroism went unseen.

Off-stage, he drinks. He drinks before events to steady his hands, drinks after events to forget. At some gatherings, white officials or socialites shake his hand, then make thoughtless or racist comments about "Indians" and "savages." He is both elevated and demeaned, paraded as an American symbol while treated as less than American.

His control slips. At one reception, after too many drinks, Ira vomits in front of none other than General Alexander Vandegrift, Commandant of the Marine Corps. The shame is immediate and public. The bond drive's handlers, angry and alarmed, decide he is a liability. Later, away from the cameras, they give him orders: he is going back to his unit. The tour will go on without him.

Ira leaves in humiliation, his unwanted celebrity clinging to him like smoke. Gerber and the others push Doc and Rene forward alone, adjusting the narrative as needed. The war bonds sell. The Treasury gets its money. The Pacific campaign continues.

When the war finally ends--Japan surrenders in August 1945--each of the three survivors goes home in a different direction, carrying invisible burdens.

Doc Bradley returns to Wisconsin, where he marries and eventually opens a funeral home. Surrounded daily by death, he finds a strange, practical peace in giving dignified endings to others, perhaps because he has seen too many undignified ones. Outwardly, he is stable, successful, a pillar of his community. Inwardly, he is scarred. Nightmares wake him sweating. Small sounds or smells drag him back to Iwo in an instant. He says very little about the war to his family.

At one point, guilt pressing on him, Doc goes to visit Iggy's mother. She greets him as her son's war buddy, eager and nervous. She wants to know how Ralph died, whether he suffered. Doc cannot bear to tell her the truth--that her boy was dragged into a tunnel and tortured beyond recognition.

"He died quick," Doc lies softly. "He never knew what hit him."

The lie is an act of compassion that tears at him. He cannot pass his anguish to her. He carries it alone.

Rene Gagnon returns to New England with high hopes. On the bond tour, he heard endless promises: jobs at big companies, chances in politics, the leverage of fame. But in the civilian world, people move on quickly. The war is over; new concerns replace old headlines. Slowly, the offers evaporate. Potential employers forget his name, or remember only briefly.

Rene drifts from one menial job to another. Eventually he settles as a janitor, mopping floors in office buildings where nobody knows, or cares, that he once stood on a fake mountain in Soldier Field as the crowd chanted his name. The resentment burns quietly. He had believed the flag photo would be his ticket. Instead, it becomes an awkward footnote he brings up too often at bars, to people who no longer want to listen.

Ira Hayes's path is the hardest. He struggles the moment he sets foot back in civilian life. The image in the photograph follows him everywhere. Strangers buy him drinks, grab his hand, say "You're that Indian from the picture!" Some mean it kindly, some not. Either way, it tightens the chain around his neck. The guilt about Harlon gnaws at him; he knows the story told to Harlon's family is wrong.

Alcohol becomes his constant companion. He drinks to quiet the screams in his head, the smell of the caves, the feel of Franklin dying in his arms. He picks up construction work when he can, but the jobs never last. Drunken outbursts, fights, and clashes with police land him in and out of jail.

After one such stint in prison, he walks out with nothing but the clothes on his back and a burning resolve. Harlon Block's parents in Texas still believe their son was not one of the iconic flag raisers. Ira cannot stand that injustice any longer.

He begins hitchhiking. Mile after mile, through desert and dust, he sticks out his thumb, rides in strangers' trucks, sleeps in ditches. He totals more than 1,300 miles on foot and in the backs of pickups, driven by guilt and a sense of obligation. At last he reaches the Blocks' modest farm.

Harlon's father, a stern, sorrowful man, greets him warily at first. Ira introduces himself, explaining that he served with Harlon, that he was in the famous photograph. They sit at the kitchen table. Harlon's mother hovers, listening. On the wall, a copy of the flag-raising photo hangs, a distant blur of bodies and motion. The official story says Hank Hansen is at the base of the staff. Ira knows better.

"He was there," Ira says quietly, voice steady for once. "Your boy. Harlon. He was the one at the base of the flag. He raised it. Not Hansen. Him."

The father studies Ira's face, measuring the man in front of him. He senses no lie, only pain. Slowly, relief and pride wash over him. His son's role in history is restored, not by the government, but by the testimony of a ruined comrade. For Ira, it is a small act of truth in a life hollowed out by half-truths.

A year later, Ira Hayes is found dead in a field near his home on the reservation, his body cold from exposure after a night of heavy drinking. The cause is simple and cruel: he drank, passed out, and never woke up. The war that did not kill him finds him in peacetime. The man in the photograph dies alone in the dirt, another statistic in a world that has moved on.

The film cuts between these individual fates and the gradual construction of a national monument. In 1954, near Arlington National Cemetery, sculptor Felix de Weldon's massive bronze representation of the flag-raising is unveiled as the United States Marine Corps War Memorial. Based directly on Rosenthal's photograph, the statue freezes the six figures in mid-motion, their effort cast in metal. Dignitaries give speeches about sacrifice and valor. Marines in dress uniform stand in formation. A band plays.

Doc Bradley, Rene Gagnon, and Ira Hayes--still alive at that time in the film's chronology--stand among the honored guests, older now, their faces lined. They see each other one final time in public. They exchange glances that carry volumes: shared trauma, shared complicity in the photograph's myths, shared losses. The monument is larger than life, but the men feel small beneath it, dwarfed not just by its scale but by the expectations and stories piled upon that one frozen moment on Suribachi.

The speeches mention none of the messiness: not the friendly fire that killed Mike Strank, not the wrong name given to Hank Hansen, not Iggy's torture, not Franklin's death on March 21, not the artillery blast that tore into Doc, not the years of nightmares and alcoholism that followed. The statue, like the photograph, simplifies. It takes a month-long slaughter and compresses it into an image that can fit on a postcard, a poster, a stamp.

In the years after the memorial's dedication, reality continues to grind on. Rene remains a janitor to his death, a man who once rode in parades now pushing a mop, gradually overshadowed by newer wars and newer heroes. He dies without ever fully reconciling his expectations with his life. Ira, as we know, is already gone, his grave one of many for veterans broken by what they endured and what they brought home. Doc runs his funeral home, raises his family, and outwardly seems fine. But he rarely talks about the war, and when he does, it is in fragments.

The narrative returns to James Bradley in 1994, sitting beside his dying father. James has collected most of the story already--from documents, from other veterans, from the Marines' own later admissions that they misidentified some flag raisers, eventually correcting the record to acknowledge Harlon Block instead of Hank Hansen. But he needs to hear it, or at least some of it, from John Bradley's own mouth.

On his deathbed, Doc chooses carefully. He does not dwell on torture, on gore, on drunken spirals. Instead, he focuses on one of the few good memories: the camaraderie of his squad, the way they laughed together even on Iwo's black sands. He tells James about Mike Strank's promise to get them all home, about Harlon's steadfastness, about Franklin's goofiness, about Iggy's shy kindness. He may mention the flag, but without triumph, more as context than as personal glory.

James listens, tears in his eyes. He understands that the story his country told itself about Iwo Jima--the simple, clean story of heroes raising a flag and winning a war--is, at best, incomplete. The real story is messier: it is about young men sent into a meat grinder, about a photograph that accidentally captured a sliver of their ordeal, and about how that image was used to sell bonds and shape memory.

As John "Doc" Bradley's breaths grow shallow and finally stop, the film's interwoven timelines resolve. We know who lives and who dies. Mike Strank dies from friendly Navy shellfire on Iwo Jima. Sergeant Hank Hansen is killed instantly by a Japanese bullet to the chest. Harlon Block dies under Japanese machine-gun fire. Ralph "Iggy" Ignatowski is captured by Japanese troops, dragged into a tunnel, tortured, and murdered in the darkness; his mutilated body is found days later by Doc. Franklin Sousley dies on 21 March 1945, cut down by Japanese machine-gun fire, bleeding out in Ira's arms. Unnamed Japanese soldiers die by the hundreds in caves and tunnels as the Marines clear the island. Many other unnamed Marines fall around the central characters in mortar blasts and sniper fire.

Later, off the battlefield, Ira Hayes dies from exposure after a drunken night, his body found in a field a year or so after he finally told Harlon's father the truth. Rene Gagnon dies an unsung janitor, never achieving the success he believed the flag photograph had promised him. John "Doc" Bradley dies in 1994 in a hospital bed, his son at his side, leaving behind a family and a funeral home and a story that has weighed on him for half a century.

The U.S. government's misidentification of the flag raisers--confusing Hank Hansen for Harlon Block--is revealed in the film as a central moral knot. The three surviving men are pressured by Bud Gerber to keep quiet about the mistake during the war, told that admitting the error might imperil the bond drive and thereby the entire Pacific campaign. They comply, living for years with that lie, until belated corrections are made. The film portrays this not as a grand conspiracy but as a grinding example of how individuals can be bent by institutional needs.

The climactic emotional confrontations have all played out by the time the credits loom: Ira threatening Rene with a bayonet on Iwo when Rene suggests claiming Ira as the sixth man; Ira denouncing the bond drive as a farce and being rebuked by Bud Gerber with the stark threat that failure would mean abandoning the Pacific; Ira's quiet, redemptive confession to Harlon's father in Texas; Doc's white lie to Iggy's mother about her son's painless death; James Bradley's final vigil at his father's bedside.

The film ends not in battle or fanfare, but in reflection. The towering bronze Marines of the USMC War Memorial loom against the sky, perpetually raising their frozen metal flag in 1954, even as the real men who inspired them move into obscurity, addiction, or death. James Bradley's voice, or the narrative anchored to his later book, frames it clearly: if there were real heroes on Iwo Jima, they are mostly the ones who never came home, who never had their picture taken, who were buried in the island's sands or the seas around it.

Yet the photograph remains, the statue remains, and the story of those "flags of our fathers" continues to be told and retold, pulled between myth and memory.

What is the ending?

In the ending of "Flags of Our Fathers," the three surviving flag raisers--Rene Gagnon, Ira Hayes, and John Bradley--return home after the war, struggling with the weight of their experiences and the burden of their newfound fame. The film concludes with a poignant reflection on the impact of war and the personal sacrifices made by the soldiers, culminating in a somber acknowledgment of the realities behind the iconic image of the flag raising.

As the film approaches its conclusion, we see the aftermath of the war and the toll it has taken on the soldiers. The narrative shifts to the three men who raised the flag on Iwo Jima, now thrust into the spotlight as symbols of American heroism. The scene opens with Rene Gagnon, who is seen attending a promotional event for war bonds. He is dressed in a suit, but his demeanor is strained, revealing the internal conflict he faces as he grapples with the glorification of their actions. The cheers of the crowd contrast sharply with his haunted expression, suggesting that the weight of his experiences in battle is far from over.

Next, we see Ira Hayes, who is struggling with the pressures of fame and the expectations placed upon him. He is depicted in a bar, surrounded by friends, but he is visibly uncomfortable. The laughter and camaraderie around him feel distant, as he battles with his own demons, including the trauma of war and the challenges of returning to civilian life. The scene captures his isolation, emphasizing the disconnect between his heroic image and his personal struggles.

John Bradley, the third flag raiser, is shown in a more reflective state. He is depicted at home with his family, but even in this intimate setting, there is a sense of unease. He is proud of his service but is also burdened by the memories of his fallen comrades. The juxtaposition of family warmth against the backdrop of his wartime experiences highlights the emotional scars that linger long after the fighting has ended.

The film culminates in a powerful scene where the three men are reunited at a memorial event. As they stand together, the weight of their shared experiences is palpable. They are no longer just symbols of heroism; they are men who have witnessed the horrors of war and are grappling with their own identities. The camera lingers on their faces, capturing the complexity of their emotions--pride, sorrow, and a deep sense of loss.

In the final moments, the film reflects on the fate of each character. Rene Gagnon continues to seek validation and recognition, but the emptiness of fame becomes increasingly apparent. Ira Hayes, despite his initial heroism, succumbs to the struggles of alcoholism and ultimately dies alone, a tragic reminder of the cost of war. John Bradley, while he finds some solace in family life, carries the burden of his memories, forever changed by his experiences.

The film closes with a poignant reminder of the sacrifices made by these men and the reality behind the iconic image of the flag raising. It leaves the audience with a sense of reflection on the true nature of heroism and the personal toll of war, emphasizing that the legacy of these soldiers is not just in their actions but in the lives they led afterward.

Is there a post-credit scene?

"Flags of Our Fathers," directed by Clint Eastwood, does not have a post-credit scene. The film concludes with a poignant ending that reflects on the themes of heroism, sacrifice, and the complexities of war. After the credits roll, there are no additional scenes or content that follow. The film focuses on the story of the six men who raised the American flag on Iwo Jima and the impact of that moment on their lives, emphasizing the emotional weight of their experiences rather than providing any further narrative after the main story concludes.

What role does John Bradley play in the story of Flags of Our Fathers?

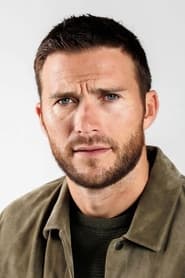

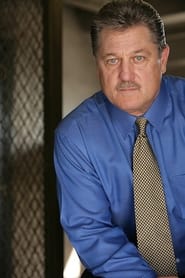

John Bradley, portrayed by Ryan Phillippe, is one of the Marines who raises the flag on Iwo Jima. He is depicted as a compassionate and introspective character, struggling with the weight of his actions and the fame that follows the iconic photograph of the flag raising. Throughout the film, he grapples with the trauma of war and the expectations placed upon him as a hero.

How does the character of Ira Hayes deal with his experiences after the war?

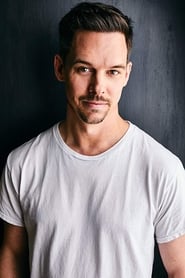

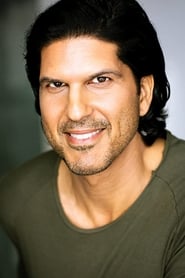

Ira Hayes, played by Adam Beach, faces significant challenges after returning from the war. He is haunted by the memories of combat and the loss of his fellow Marines. Despite being celebrated as a hero for his role in the flag raising, he struggles with alcoholism and the burden of his newfound fame, feeling disconnected from the American public that idolizes him.

What is the significance of the flag raising scene at Iwo Jima?

The flag raising scene at Iwo Jima is a pivotal moment in the film, symbolizing hope and victory amidst the horrors of war. It captures the emotional intensity of the moment, showcasing the camaraderie among the Marines. The scene is both triumphant and tragic, as the men involved are later confronted with the harsh realities of their experiences and the propaganda that follows.

How does the film depict the relationship between the soldiers and the media?

The film illustrates a complex relationship between the soldiers and the media, particularly through the characters of John Bradley and Ira Hayes. After the flag raising, the Marines are thrust into the spotlight, with their images used to promote war bonds. This creates tension as the soldiers feel exploited and misunderstood, struggling to reconcile their traumatic experiences with the glorified narratives presented to the public.

What internal conflicts does the character of Rene Gagnon face throughout the film?

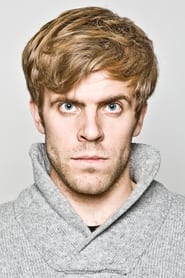

Rene Gagnon, portrayed by Jesse Bradford, experiences internal conflict as he navigates the expectations of being a war hero. He grapples with feelings of inadequacy and the pressure to embody the ideal soldier. Gagnon is torn between his desire for recognition and the emotional toll of his wartime experiences, leading to a profound sense of disillusionment as he confronts the realities of war and its aftermath.

Is this family friendly?

"Flags of Our Fathers," directed by Clint Eastwood, is a war film that explores the events surrounding the Battle of Iwo Jima during World War II and the subsequent raising of the American flag on Mount Suribachi. While the film is a historical drama that aims to honor the soldiers' sacrifices, it contains several elements that may be objectionable or upsetting for children or sensitive viewers.

-

Graphic War Violence: The film depicts intense battle scenes, including gunfire, explosions, and the aftermath of combat, which can be quite graphic and disturbing.

-

Death and Injury: There are scenes showing the injuries and deaths of soldiers, which may be emotionally distressing. The portrayal of the physical and psychological toll of war is a central theme.

-

Emotional Trauma: Characters experience significant emotional struggles, including grief, survivor's guilt, and the impact of war on their mental health, which may be heavy for younger audiences.

-

Mature Themes: The film addresses themes of heroism, sacrifice, and the complexities of war, which may be difficult for children to fully understand or process.

-

Language: There are instances of strong language used by characters, reflecting the harsh realities of military life.

Overall, while "Flags of Our Fathers" is a poignant exploration of history and sacrifice, its mature content and intense scenes may not be suitable for younger viewers or those sensitive to depictions of war.