Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

A veteran of the Mexican War, Jeremiah Johnson leaves organized society and arrives in the Rocky Mountains determined to live as a solitary trapper. He endures a harsh first winter and begins with a .30-caliber Hawken percussion rifle as his principal firearm. While traveling through the high country, he discovers the frozen corpse of a fellow mountain man known as Hatchet Jack; Jack grips a larger .50-caliber Hawken rifle in his dead hands, and Jack's will, found with the body, names the finder as the rifle's heir. Johnson takes the .50-caliber weapon and thereafter carries it as his main armament.

Armed with the heavier rifle, Johnson inadvertently interrupts an elderly trapper's grizzly hunt. The old man, Chris Lapp, whom others call "Bear Claw," had pursued the bear with friends and found the animal wounded and dangerous; Johnson's arrival and the fire of his new rifle disrupts the operation. Lapp, an eccentric and experienced mountain man, takes Johnson under his wing and instructs him in wilderness craft: tracking, trapping, how to weather the seasons, and how to relation himself to the tribes and the land. During this period Johnson has a run-in with Paints-His-Shirt-Red, a Crow chief; the encounter establishes a wary awareness between Johnson and the Crow people that appears in quiet confrontations and measured gestures during subsequent years.

While living among the mountains and learning from Lapp, Johnson meets other mountain men. He discovers Del Gue, a man buried up to his neck in sand and half-buried by Blackfoot raiders who had set him aside and left him to die. Gue tells Johnson that the Blackfeet stole his trade goods and horses; Johnson agrees to help him recover what was taken, and the two men travel to locate the Blackfoot camp. They observe the encampment and, against Johnson's counsel to avoid retaliation, Gue decides to strike at night. Gue opens fire into the Blackfoot camp and a firefight erupts; Johnson and Gue then kill the Blackfeet warriors present during the raid. After the attack, Gue takes several Blackfoot horses and removes scalps from the dead men. Johnson, disgusted by the unnecessary bloodletting and scalping, leaves Gue and returns to the mountain country alone.

Shortly thereafter, Johnson and the young boy he has taken under his care encounter Christianized Flathead tribesmen. The boy is the surviving child of a woman whose cabin had been attacked; the mother, rendered furious and grief-stricken by the slaughter of her husband and others, has compelled Johnson to adopt her son, whom Johnson names Caleb. The Flatheads receive Johnson and Caleb with honor, and because Johnson gives the Flathead chief the Blackfoot horses and the scalps he brought back--an act Johnson intends as a gesture of peace and restitution--the chief finds himself obliged by custom either to offer an even greater gift or to kill his guest to restore honor. To avoid killing Johnson, the Flathead chief gives his daughter Swan to Johnson in marriage, and the couple is wed according to Flathead custom. After their union, Del Gue breaks off from Johnson's company and departs alone into the mountains. Johnson, Swan, and Caleb then move into the wilderness together.

Johnson selects a site, builds a cabin, and settles into domestic life with Swan and the boy. He hunts and traps, he fixes the cabin, and he teaches Caleb the daily arts of mountain living while Swan tends the household. Their life is simple and orderly, and Johnson grows attached to the family he has formed.

That stability ends when a U.S. Army cavalry detachment arrives at the mountain pass. The troops are on a mission to rescue a stranded wagon train of settlers, and they compel Johnson to act as their guide through the high passes despite his reluctance to leave his wife and the boy alone. While leading the cavalry, Johnson advises the officers to avoid passing through a Crow burial ground, explaining the sacredness and the danger such a passage could provoke. Lieutenant Mulvey, the troop's officer, disregards Johnson's warning and orders the unit to ride directly through the grave site. The soldiers pass over the ground and the burial cairns, leaving the Crow graves disturbed.

After completing the mission, Johnson retraces the route home. On the way back he notices the graves that he had warned about now number strange offerings: he sees Swan's blue trinkets hanging from the Crow markers. Alarmed, he hurries toward his cabin and reaches it to discover Swan and Caleb have been killed. Both victims lie dead in their home, slain in an act of retaliation linked to the desecration of the Crow burial ground. Johnson finds their bodies and recognizes that the slaughter of his new family is a revenge killing by Crow warriors for the army's intrusion and the disturbance of the graves.

Consumed by grief and rage, Johnson sets out to track the killers. He follows their trail through the mountains and engages them in combat, killing several of the responsible warriors. During one final pursuit he captures a heavy-set Crow man who has been part of the raiding party. That captive, coming to terms with his fate, begins to sing a death song once he realizes escape is impossible; Johnson chooses not to execute him and allows him to live. The survivor returns to his people and carries word of the mountain man's vengeance, telling the tribe of Johnson's single-handed campaign against those who slayed his family. The tale spreads and the Crow take counsel; the tribe sends a series of their most skilled warriors to kill Johnson in retribution, but each man is sent singly, not in mass, and Johnson meets and defeats them one by one in separate confrontations.

Johnson dispatches the Crow warriors in a sequence of encounters that test different facets of his mountain skills. In each meeting he relies largely on weaponry, stealth, and the rugged defensive positions he can fashion in the terrain; he shoots or wounds each attacker and survives the combats. As the pattern of single duels continues, Johnson's reputation grows among both whites and Indians. The Crow, rather than overwhelming him with numbers, continue to honor their internal code by challenging him with individual champions. Johnson answers each challenge with force, and each warrior sent against him falls in battle. The tribe's grief over lost members manifests in periodic offerings left at a monument they erect to the mountain man's deeds; they place talismans and trinkets there, acknowledging his prowess even while the feud between him and the Crow nation persists.

At one point Johnson encounters Del Gue again on the trail. They meet briefly and exchange words as men who have walked the same mountain paths; Gue remains a figure who has chosen a reckless, tramping life and later drifts away once more. Johnson also returns to the cabin of Caleb's mother to find she has died since his departure; her dwelling is now occupied by a settler named Qualen and his family, who live in the old woman's place. Nearby, the Crow maintain their monument to Johnson by leaving periodic offerings and tokens, an odd mixture of respect and ongoing enmity.

Johnson renews a relationship with his old mentor Chris Lapp in a final encounter at a mountain rendezvous. Lapp observes the visible toll the prolonged feud has taken on the younger man and recognizes the loneliness of Johnson's path. They talk, and Lapp remarks that Johnson "has come far," to which Johnson replies "Feels like far." Lapp asks "Were it worth the trouble?" and Johnson gives the terse, ambiguous response "What trouble?" The exchange indicates the distance Johnson has traveled from his former life and the costs he has already borne.

Afterward, Johnson has a short, wordless meeting with Paints-His-Shirt-Red, the Crow chief involved earlier in his life. They sit on their horses at a measured distance across the plain. Johnson reaches for his rifle, preparing for a possible attack, but the elder chief raises his bare hand, palm outward--a gesture of peace. Johnson lowers his weapon and returns the gesture slowly. Their reciprocal, unspoken signal ends the immediate cycle of vengeance between man and tribe. The movie closes with a lingering image of the mountains and, in the soundtrack that follows, the lyric "And some folks say he's up there still," signaling that Johnson remains in the high country, his fate carried forward in story and song.

More Movies Like This

Browse All Movies →What is the ending?

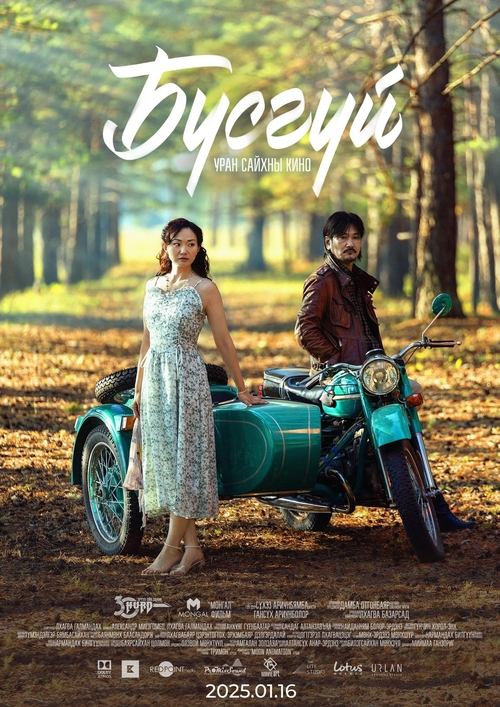

The ending of The Wolves Always Come at Night shows the young Mongolian couple, Davaasuren and Otgonzaya, forced to leave their rural home after a devastating sandstorm kills much of their livestock. They move to the city of Ulaanbaatar, struggling to adapt to urban life while haunted by memories of their past.

Expanded narrative of the ending scene by scene:

After a long search in the desert, Davaasuren finds half of his goat herd dead, scattered across the sand. The camera follows him closely as he weaves through the corpses, his face showing shock and grief. There is no music or dialogue in this moment, allowing the audience to fully absorb the weight of the loss alongside him. This scene marks a turning point, as the couple realizes their traditional pastoral life is no longer sustainable.

Back at their home, Davaasuren and Otgonzaya sit silently, mourning the loss of their livestock. The silence and stillness emphasize the depth of their despair. They decide that they must leave the countryside and move to the city to find a new way to survive.

The film then shows the family packing up and driving away from their old life. As they pass a herd of goats on the road, the visual contrast highlights what they are leaving behind. The landscape changes from harsh desert to the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar, signaling a dramatic shift in their environment and lifestyle.

Upon arrival in the city, the couple assembles their home, which they have transported on the back of a truck. The urgency is palpable--they have no other place to sleep. This scene captures the physical and emotional challenge of rebuilding their lives from scratch in an unfamiliar setting.

The narrative then follows Davaasuren and Otgonzaya as they struggle to adjust to urban life. Davaasuren takes a job excavating land, a stark contrast to his nomadic past. One night, after a long shift, he is shown singing a melancholic folk song alone in a bar rather than returning home, revealing his internal conflict and sense of loss.

In a parallel to the film's opening, Davaasuren hears horses in the night and goes outside to investigate, but finds nothing. This moment symbolizes how the past continues to haunt him, even as he tries to move forward.

The film closes on this note of unresolved tension between past and present, with the couple physically in the city but emotionally tethered to their former life. Both Davaasuren and Otgonzaya survive the transition, but their fate is one of ongoing struggle and adaptation rather than resolution.

Key characters at the end:

- Davaasuren: Grieving the loss of his herd, forced to abandon pastoral life, struggles with his new urban job and identity.

- Otgonzaya: Shares the burden of loss and the challenge of adapting to city life alongside her husband.

No other main characters are central to the ending. The film's final scenes focus intimately on this couple's emotional and physical journey from rural to urban existence.

Is there a post-credit scene?

The movie The Wolves Always Come at Night (2025) does not have a post-credit scene. None of the available detailed sources or reviews mention any additional scene after the credits. The film concludes with a poignant final scene where Daava is reunited with an old friend, which serves as the emotional closure of the story rather than a setup for further narrative in a post-credit sequence.

The film is a documentary-style narrative focusing on the emotional and physical journey of a family forced to leave their rural life due to environmental loss, and it ends on a reflective, somber note without extra scenes after the credits.

What are the main challenges the family faces in their daily life in The Wolves Always Come at Night?

The family in The Wolves Always Come at Night faces challenges such as harsh climate change effects including desertification, unpredictable severe sandstorms, and the struggle to maintain their traditional pastoral lifestyle. They also deal with emotional and psychological pressures caused by migration and adapting to new work environments, such as the father working long hours in a quarry away from his family.

How does the film depict the relationship between the family and their animals?

The film shows a deep love and care for animals, particularly through Daava's interactions with his goats and horses. Scenes include helping goats through difficult births and the emotional moment when Daava has to sell his prized stallion, highlighting the strong bond between the family and their livestock.

What role does climate change play in the story of The Wolves Always Come at Night?

Climate change is a central theme, portrayed through the impact of desertification and extreme weather events like severe sandstorms that threaten the family's livelihood. The film includes documentary footage of a town hall meeting discussing these environmental changes, emphasizing how climate change makes traditional pastoral life increasingly untenable.

How does the film blend documentary and fictional elements in its storytelling?

The Wolves Always Come at Night is a hybrid film combining documentary footage with dramatized and fictionalized scenes. This approach creates an immersive narrative that captures real experiences and emotions while using staged scenarios to underline key themes such as migration, loss, and adaptation to change.

What emotional and psychological effects does the family's situation have on its members?

The film reveals the emotional and psychological toll on the family, especially the father, Daava, who struggles with the loss of his nomadic lifestyle and the demands of his new job. Scenes show moments of melancholy, such as Daava singing a folk song alone after work, and the family coping with uncertainty and fear during harsh weather events, illustrating their vulnerability and resilience.

Is this family friendly?

There appears to be some confusion in the query. The movie "The Wolves Always Come at Night" is actually produced in 2024, not 2025. Based on the available information, the film focuses on a Mongolian family dealing with the impacts of climate change and desertification, which might be emotionally challenging for some viewers.

For potential objectionable or upsetting scenes: - The film's themes of displacement and environmental degradation might be distressing for sensitive viewers. - The overall narrative could be emotionally intense, especially for children or those who find environmental despair upsetting. - There is no specific mention of graphic or violent content, but the documentary-style exploration of the family's struggles could still be emotionally taxing for some audiences.

It is important to consider these factors when deciding if the film is suitable for children or sensitive viewers.

Does the dog die?

There is no movie titled "The Wolves Always Come at Night" produced in the year 2025. The film "The Wolves Always Come at Night" was released in 2024, not 2025. It follows a Mongolian herding family forced to relocate to Ulaanbaatar due to climate change and its impacts on their lifestyle. The search results do not mention a dog's death in this film. If you are referring to a different movie, please provide more details.