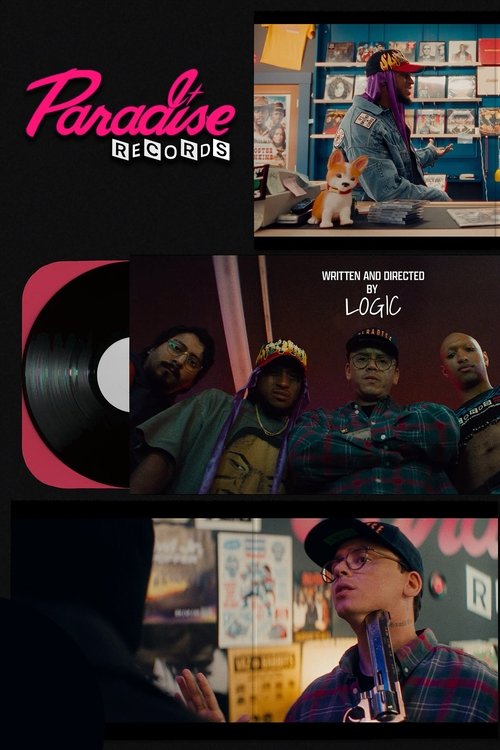

Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

The film opens in 1969 with Leon Russell and record executive Denny Cordell standing in a cramped office strewn with contracts and record sleeves; they form Shelter Records together and launch it as a joint enterprise. Leon Russell takes an active role in running the label alongside Cordell through the early 1970s, signing acts and overseeing recording projects. The partnership continues for several years, and the camera follows administrative meetings and studio sessions that show Russell embedded in the business side as well as the creative side. In 1976 the partnership fractures: Russell and Cordell experience a falling out that escalates into a legal dispute. After negotiations and a settlement, Cordell takes sole ownership of the Shelter Records name and catalog, and Leon Russell departs to establish a new imprint. Immediately after the settlement, Russell announces the formation of Paradise Records and begins assembling the physical infrastructure and personnel for his second label venture.

Russell builds Paradise Records around a multi-room production complex that he calls Paradise Studios. The studio complex contains two dedicated audio sound stages and one television production stage; Russell installs a remote recording truck and a remote television production bus that can operate independently or augment the on-site stages. The narrative follows technicians, engineers and musicians as they set up tape machines, lighting rigs and camera positions, and it records the first sessions that take place in the newly outfitted rooms. The camera moves through corridors lined with gold records and rehearsal rooms where artists test microphone placements; engineers calibrate consoles and patch bays while stagehands wheel camera dollies onto the television stage.

Within months Paradise Studios becomes more than a record label headquarters; it hosts a weekly live television music program titled New Wave Theatre that the studio produces and the USA Network broadcasts. The production crew rigs cameras and live audio feeds for the show, and the film chronicles the making of multiple New Wave Theatre episodes: cueing performers, switching live camera angles, inserting pre-recorded segments and handling the network's technical demands. The series regularly fills the television stage with rising acts and a rotating slate of performers, and the studio team adapts the space to accommodate each episode's specific staging requirements.

Paradise Studios' production slate expands beyond the weekly series. The facility produces promotional music videos for established recording artists: the crew shoots and edits videos for James Taylor and for Randy Meisner, executing location setups, close-ups of performers, and multi-camera tracking shots on the television stage. Russell commissions long-format concert and documentary-style video projects as well, which the studio completes for Willie Nelson, J.J. Cale, Bonnie Raitt and Leon Russell himself. The documentary-style shoots involve multi-day setups: camera crews capture extended live performances, capture cutaway interviews, and cut together long-form pieces for release. The film shows production meetings where Russell and directors plot camera blockings for Nelson's sequences, where J.J. Cale conducts soundchecks on the Paradise audio stages, and where Bonnie Raitt schedules late-night studio rehearsals.

Musicians and technicians pass through Paradise Studios and train under the studio's engineers and staff. Steve Ripley works at the facility early in his career, learning engineering and production techniques on the sound stages. Members of the band Concrete Blonde also use Paradise Studios as a place of practical education, recording sessions and learning studio craft. The narrative traces their hands-on experiences: Ripley dialing equalization, Concrete Blonde members setting microphone distances, and engineers teaching how to capture live room ambience. The film notes that Steve Ripley later forms the retro-country group The Tractors; it shows Ripley leaving sessions at Paradise with notebooks of techniques and arrangements that he later adapts to his own band's recordings.

In June 1979 Paradise Studios hosts a live recording session featuring J.J. Cale and Leon Russell performing together. The film follows the musicians into the large audio stage where they set up and begin playing songs for a live-in-studio audience; engineers place microphones on cabinets and overheads, set compressors and route signals through the studio's mixing console. J.J. Cale functions in multiple roles during these sessions: he performs and he works as an engineer at Paradise, operating the controls and shaping the sound of the performances. Over the course of the June dates, Cale and Russell record a set that includes multiple tracks later associated with Cale's Fifth album. The camera captures them performing "Sensitive Kind" with close-ups on fingerpicking and vocal phrasing, then moves to a take of "Lou-Easy-Ann" where the rhythm section locks and the engineers adjust levels on the fly. The session continues through "Fate of a Fool," where Russell contributes piano fills, through a raw take of "Boilin' Pot" with its loose groove, and it concludes with a rendition of "Don't Cry Sister" captured in the large room's natural reverb.

The June 1979 footage remains archived and unseen for decades. In 1982 Leon Russell sells the Paradise Studios complex; the film depicts him signing transfer documents and handing over keys as crews move equipment and merchandise out of offices. After the sale the complex houses Alpha Studios, which installs its own signage and runs sessions in the same rooms formerly occupied by Russell's staff. Later Oracle Post operates the facility; the narrative depicts tradespeople installing new consoles and redesigning control rooms as the building passes between occupants. In 2001 technicians in Nashville uncover film cans and videotapes from the old Paradise archival shelves; the discovery reveals the 1979 J.J. Cale and Leon Russell session footage that had been stored and forgotten. Archivists transport the material to a restoration lab, where technicians inspect the tapes, bake them if necessary, and digitize the performances. They identify multiple tracks from Cale's Fifth album on the reels and catalog each song by take and timecode.

The restoration process culminates in a formal release. In 2003 the previously unseen Paradise Studios session footage is issued to the public as J.J. Cale featuring Leon Russell: In Session at the Paradise Studios. The film shows the packaging of the release, liner notes being written, and promotional materials being prepared. The credits of the release list Cale as both performer and engineer on the original tapes, and the promotional campaign highlights the rediscovered nature of the 1979 session. Meanwhile, Paradise Records as a label continues to exist in the broader marketplace; distribution and manufacturing of Paradise Records' material come under the auspices of Warner Bros. Records, which handles pressing, distribution and wider commercial logistics for the label's releases.

Throughout the decades the physical site that once housed Paradise Studios undergoes further transitions. After Alpha Studios and Oracle Post, the facility remains an active production space and in 2014 it reopens under new management as a secondary multi-room production facility for Bang Zoom! Entertainment. The narrative shows Bang Zoom! staff installing voice-over booths, configuring multi-room routing and repurposing the television stage for animated series dubbing and post-production. Technicians hang new studio signs and update the address listings; they run cable through walls and place modern monitors in control rooms while staffers paste new logos onto directory boards. The final sequences return to archival images and footage: the original Paradise sound stages empty at night, the June 1979 performance footage playing on a restoration monitor, and, in the last shots, the 2003 release packaging sitting on a shelf in a modern production office.

The story contains no on-screen deaths among the people involved in the recorded account. No character kills another, and the narrative provides no scenes of violence or mortality tied to specific individuals. The chronology closes on the redistributed and repurposed studio spaces and on the public release of the rediscovered session. The last frame shows the restored footage credits rolling across the screen with J.J. Cale and Leon Russell listed as performers and the Paradise Studios name appearing beneath their credits, and then the film ends with a single shot of the repurposed production facility bearing Bang Zoom! signage, marking the site's continued use in media production.

What is the ending?

The ending of Paradise Records (2025) sees Cooper, the record store owner, confronting the culmination of his financial and personal struggles as the chaotic day reaches its peak. After a series of escalating events involving his shady uncle, mobsters, and bungling robbers who take the store hostage, Cooper manages to navigate the turmoil, but the fate of the store and its staff remains uncertain, leaving a bittersweet resolution to his fight to keep Paradise Records alive.

Expanding on the ending scene by scene:

The final act unfolds inside the cramped, cluttered record store, where tensions have been mounting all day. Cooper is dealing with the fallout from his uncle's money-laundering scheme, which has drawn dangerous mobsters to the store demanding cash. The two inept robbers who earlier botched a heist have taken everyone hostage, adding to the chaos. Cooper's cousin T Man and the other employees, including the calm Melanie and the sensitive Table, are caught in the middle of this hostage situation.

As the robbers grow increasingly desperate and unpredictable, Cooper tries to keep the peace, using his wit and knowledge of the store and its patrons to defuse the situation. The store's atmosphere is thick with smoke and the smell of vinyl, underscoring the claustrophobic tension. Cooper's father, known for his wisecracking and sexual bravado, makes a brief appearance, adding a layer of familial complexity to the unfolding drama.

In a pivotal moment, Cooper confronts the mobsters, attempting to negotiate and protect the store's remaining assets. The robbers' incompetence leads to a comedic yet tense standoff, where Cooper's quick thinking prevents violence. Meanwhile, Slaydro, the local dealer under house arrest who drifts through the store offering odd advice, provides moments of levity amid the chaos.

The climax is marked by a surreal black-and-white sequence featuring Jay and Silent Bob, a nod to indie cinema and a symbolic blessing on Cooper's struggle. This sequence contrasts sharply with the otherwise gritty realism of the film, highlighting the absurdity and unpredictability of the day.

As the hostage situation resolves, Cooper faces the harsh reality of the store's financial troubles. The offer from local arcade owner Mike Hawk to take over Paradise Records looms as a possible lifeline, but Cooper's decision is left ambiguous, reflecting the uncertain future of small businesses in a changing world.

In the closing scenes, Cooper and his employees share a quiet moment in the store, the weight of the day's events settling in. The fate of each main character is as follows:

- Cooper remains the determined but weary owner, still fighting to save Paradise Records but aware of the challenges ahead.

- T Man continues as Cooper's loyal but flawed cousin, still grappling with his own prejudices and role in the store.

- Melanie, the voice of reason, stays committed to the store and its community.

- Table, the sensitive employee, remains a steady presence amid the chaos.

- Cooper's uncle and the mobsters exit the story, their schemes thwarted but leaving lasting consequences.

- The robbers are apprehended or flee, their bungling heist ending in failure.

- Slaydro drifts away, his role as comic relief intact.

The film closes on a note of cautious hope, emphasizing the resilience of community and the enduring spirit of small businesses despite overwhelming odds.

Is there a post-credit scene?

Yes, the movie Paradise Records (2025) does have a post-credits scene, but it is not a traditional narrative scene. Instead, after the credits, there is a set of bloopers that highlight the fun and camaraderie during the making of the film. These bloopers serve as a lighthearted epilogue, showing the cast and crew enjoying themselves, which complements the film's comedic and ensemble spirit. There is no mention of a separate story-related post-credit scene or teaser.

What role does Cooper's uncle play in the story of Paradise Records?

Cooper's uncle, also played by Logic, is involved in a money-laundering scheme and is trying to get money to fend off mobsters. This situation brings additional pressure on Cooper, as the mobsters eventually come to him for the rest of the cash, complicating his efforts to save the record store.

Who are the two robbers that take hostages in Paradise Records, and what is their significance?

Two less-than-bright robbers, played by Nolan North and Oliver Tree, take the record store gang hostage after a botched heist earlier in the day. Their presence escalates the chaos in the store and adds to the comedic and absurd tone of the film.

What is the character Slaydro's situation and role in Paradise Records?

Slaydro, portrayed by Tony Revolori, is a local dealer under house arrest who floats through the store offering non sequiturs and bad advice. His character adds a surreal and humorous element to the story, contributing to the film's fast-talking, stoner-logic atmosphere.

How does Melanie fit into the dynamics of Paradise Records?

Melanie, played by Mary Elizabeth Kelly, is the only sane employee at Paradise Records. She works alongside Cooper and the other staff, often amidst the bickering and bantering, serving as a grounding presence in the chaotic environment of the store.

What challenges does Cooper face in trying to keep Paradise Records open?

Cooper struggles with financial problems, including defaulting on a loan that threatens the store's foreclosure. He also deals with internal issues like employee theft suspicions and external pressures from his uncle's mob-related troubles and the potential takeover offer from a local arcade owner, Mike Hawk.

Is this family friendly?

The movie Paradise Records (2025) is not family friendly; it is rated R for pervasive language, crude sexual material, drug content, some violence/grisly images, and brief nudity.

Potentially objectionable or upsetting aspects for children or sensitive viewers include:

- Frequent use of strong profanity, including racial slurs.

- Crude sexual content and brief nudity.

- Drug use and depiction of drug dealers, including scenes involving escalating intoxication.

- Some violence and intense scenes, including an armed robbery and grisly images.

- Situations that may be intense or upsetting due to the mounting pressures on the characters and the chaotic events unfolding during the day.

Overall, the film contains mature themes and language that make it unsuitable for children and potentially uncomfortable for sensitive audiences.