Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

A small living room in the Keller house fills with noise and disorder as the story opens. Helen Keller, a young child who has been deaf, blind, and unable to speak since a severe sickness in infancy, flails and rages when she cannot get what she wants. She throws herself across furniture, bites and strikes out, scares the household with sudden shrieks, and seizes objects without understanding their use. Her mother, Kate Keller, moves between anger and helpless comfort; she tries to calm Helen and soothe her bruises. Her father, Captain Arthur Keller, speaks angrily and impatiently when Helen disrupts the family, and he cannot find a way to manage his daughter's violent outbursts. The Kellers' domestic routine breaks down because no one can teach Helen to connect words or signs with things in the world.

Kate and Arthur meet in the parlor and decide to seek outside help. They write to the Perkins Institution for the Blind, describing Helen's behavior and pleading for someone to come teach her. The director of the Perkins school, Dr. Alexander Graham Anagnos, reads the Keller letter. He selects a former Perkins pupil, Anne Sullivan, to travel to the Keller home as a tutor. Anne is introduced to the family when she arrives; she bears the wear of her life at Perkins but stands determined and uncompromising. She tells the Kellers that she intends to teach Helen and that she will not be content with partial success; she insists that the child must learn names for things and that the family must cooperate.

Anne immediately meets Helen. The child lunges and bites at Anne's hands, throws dishes, and screams. Anne presses her hands against Helen's to stop the flailing and declares rules for the household: no one will indulge Helen's tantrums and no one will call her "baby" when she misbehaves. Anne places herself between Helen and the adults, refusing to accept the family's pattern of pity and avoidance. She tells Captain Keller that she intends to stay in the house and to train Helen directly; she will not send the child away, and she will not accept softened measures. The captain questions her methods, but Kate, exhausted and hopeful, allows Anne to remain as a live-in instructor.

Anne begins teaching with direct, physical methods. She forces Helen's hands to remain in certain positions so that the girl learns to focus on finger motions. At meals Anne spells the names of food into Helen's palm, pushing the manual alphabet letters slowly and repeatedly until Helen's fingers feel the motion in her hand. Anne takes a loaf of bread to the table and forces Helen's hand to touch the crust while she spells b-r-e-a-d into her palm, over and over. Helen resists; she grabs the bread, stuffs it into her mouth, and throws plates. Anne restrains Helen's hands until she stops fighting, making it clear that eating will not occur without paying attention to the letters.

The household reacts. Kate, who has allowed indulgence, watches anxiously as Anne refuses to give in to Helen's tantrums. Captain Keller, stern and proud, distrusts some of Anne's harsher tactics, but he also recognizes that Anne does not waiver. Anne isolates Helen from excessive affection that spoils her behavior. She stops Helen's access to certain comforts when Helen acts out. Anne also trains the servants and family members to refuse the child's demands when she misbehaves; they must spell names into her hand and require attention. Anne tells them that she will teach Helen words by pushing the manual alphabet through the skin of her hand, linking those letters to specific, repeated experiences.

Anne's instruction moves beyond the dining room to the house's outdoor pump. She decides that water, a sensory and regular part of life that Helen touches often, can become the first clear bridge between physical experience and finger-spelled language. One afternoon at the well pump, Anne forces Helen to come with her. She sets Helen's small hand under the stream of water. Helen notices the temperature and the flow but does not yet connect that sensation with a word. Anne grips Helen's hand and places it against her own palm; with the other hand she pushes the letters w-a-t-e-r into Helen's palm, hard and repetitively. Helen resists, pulling her hand away, scratching and biting Anne's knuckles. Anne digs in and holds Helen's hands under the steady cold water, repeatedly forming the fingers to spell w-a-t-e-r into Helen's palm. The child screams and struggles, trying to wrench herself free. Anne will not stop. She keeps the letters spelled into the small hand and the water running over it until Helen's movements slow.

After a long and grueling struggle at the pump, Helen's fingers gradually still. Her face, streaked with tears and mud from earlier tantrums, changes as she feels the steady flow against her skin and the patterned touch of the letters. The motions of Anne's fingers and of the water combine in Helen's perception. For the first time, a connection forms: the repeated finger shapes become associated with the stream flowing over her hand. Helen suddenly grasps Anne's gesture, and she presses her fingers to Anne's hand and repeats the spelled sequence she has felt in her palm. She signs W-A-T-E-R into Anne's palm, using the manual alphabet in turn to communicate back. Anne, sensing the pivot, continues to spell the word while releasing her hold slowly. Helen's breathing changes; she laughs, then cries. She understands that the letters correspond to the flowing water she feels.

The breakthrough at the pump does not end the work; Anne continues to teach Helen the names of things with systematic rigor. She brings objects into Helen's hands: a doll, a spoon, a chair, a cat. She spells their names into Helen's palm the same way she did with water, tying each finger motion to a tactile experience. When Helen touches the doll and the letters d-o-l-l are spelled into her palm, she begins to repeat those motions back to Anne. She learns to sign the word for food while the bread crust scratches her fingers and the letters b-r-e-a-d move against her skin. Anne insists on attention, on placing Helen's hands on the object as she spells, so that Helen will not merely repeat motions but will link them to actual things and actions.

As Helen accumulates names, her behavior changes. She no longer flings objects blindly when someone takes something from her; she asks for the item by spelling its name into another person's hand. Her shrieks fade into focused concentration. The Kellers watch these shifts with a mix of astonishment and emotional release. Kate embraces Anne and thanks her when Helen first gestures "mother" into her hand, and Captain Keller lays a heavy hand on Anne's shoulder and says nothing, a sign that he recognizes the results though his pride keeps him from overt emotion.

Anne's methods meet resistance from outside pressures as well. Relatives who have earlier advised shipping Helen to a distant institution appear and complain that Anne is too strict or that the work is impossible. The captain hears neighbors' opinions, but Anne stands firm. She refuses to yield to anyone who would allow Helen to remain unlabeled and uncontrolled. Anne also contends with Helen's contradictory clinginess and aggression; when Helen misdirects affection, Anne corrects her hand placements and continues to spell names until Helen learns to focus.

Months pass with disciplined lessons, measured in repeated letterings and repetitive experiences. Anne expands Helen's world beyond the house; she takes the girl to the garden to feel soil and leaves while spelling g-a-r-d-e-n into her palm, to the kitchen to touch the warmth of a stove while spelling s-t-o-v-e, and to the parlor where books' textured pages receive the letters b-o-o-k. With each successful mapping of a word to a sensation, Helen grows more articulate in the manual alphabet. She begins to press the spelled letters into other people's hands to request things rather than resorting to biting or screaming.

The family's relationships shift. Kate, who has lived in fear and embarrassment over Helen's public outbursts, now shows a cautious optimism; she smiles when Helen signs simple sentences or seeks her by spelling m-o-t-h-e-r, carefully touching Kate's palm with deliberate motions. Captain Keller, who had wanted to control his daughter with a firm hand or to conceal her disability, learns to defer to Anne's expertise. He allows Anne authority over household discipline in ways he would not have accepted at first. The house settles into new routines that Anne maintains: the manual alphabet remains central to every interaction, and every caregiver must spell consistently and insist upon attention.

Helen's progress accelerates. She begins to form chains of letters that make up small phrases. She understands commands such as "wash," "eat," and "sit." She learns that words can describe not only immediate tactile experiences but also absent things; Anne spells the names of distant relatives and scenes, training Helen to think beyond the present touch. When family members speak aloud, Anne continues to emphasize the letters in the palmar alphabet so that Helen learns the association between spoken language and finger-spelling.

No member of the household dies in the course of these events. There are no killings or physical eliminations. The conflict is psychological and educational: it is a struggle over behavior, instruction, and will. The central violent acts consist of Helen's tantrums and Anne's forceful physical instruction; the only blood shed is the visible scratch marks Helen leaves on Anne during their fights, and no one kills or is killed.

As Helen masters more words, she begins to use language to express feelings. One afternoon after a prolonged set of lessons, Helen surprises Kate by spelling "MOTHER" into her palm and then pressing the same sequence into Anne's hand to identify both women by name. She then composes a short sequence of letters to indicate that she wants to go outside; she moves with clear purpose rather than being propelled by impulses. The family watches as Helen recites, through finger-spelling, requests and observations that show comprehension. Anne sits with Helen at a table and watches as the child fingers phrases in neat sequences.

The climax of the story is not a single dramatic battle after the pump but a string of lessons that show Helen's mastery growing from those early victories. With every sign Helen learns, Anne expands her curriculum. She begins teaching Helen not only concrete nouns but also verbs and descriptors, making the child capable of forming more complicated requests. Helen learns to say in the manual alphabet, with deliberate accuracy, that she wants water, that she wants her doll, that she loves her mother. She also learns to use language to correct others and to describe past mishaps. The family sees the tangible outcome of Anne's unrelenting methods: a child who once lived in a world of isolated sensation now participates in shared communication.

In later scenes, Anne and Helen sit together in the Keller garden. Helen touches a flower and Anne spells f-l-o-w-e-r into her palm; Helen repeats the letters and then leans to feel the petals directly, the motions of her fingers tracing shapes on Anne's hand as if telling a story. Kate looks on nearby and weeps quietly as she watches the slow but unmistakable transformation. Captain Keller stands at a distance and slowly approaches, placing his hand against Anne's and then reaching for Helen. He allows Helen to place her small hand atop his, and she spells "FATHER" into his palm, a moment that shows the bridge Anne has built between Helen and her parents.

In the final sequence, Helen demonstrates a new capacity for independent communication. She enters the parlor where guests or family members have gathered, and she moves among them, placing her fingers in their hands to spell the names of the objects she touches. She calls for her mother by spelling m-o-t-h-e-r and for Anne by spelling a-n-n-i-e, and she requests a book by spelling b-o-o-k. Anne sits behind Helen and watches as the girl touches the curl of her hair, the edge of a table, and then returns to Anne's hand to spell the sequence for "teacher." Helen's fingers move with speed and confidence now; she initiates conversation by spelling into others' palms and by responding when people spell words back to her. The family members, who previously spoke for Helen or protected her from social contact, now listen to the child's spelling and answer her directly.

The story closes with a domestic scene that repeats motifs of the opening but with reversed roles. Where before Helen had raged and lashed out in panic and confusion, she now channels those energies into deliberate language learned by sweat and insistence. Anne and Helen sit together while Kate brings a tray of food; Helen asks for bread by spelling b-r-e-a-d and then thanks her mother by placing her fingers in Kate's hand and spelling t-h-a-n-k-s. Captain Keller watches them from the doorway, an expression that mixes pride with reserved emotion. Anne looks at Helen, touches her forehead, and then folds the girl into an embrace, holding her hand in a way that Anne has used throughout to form letters. Helen returns the gesture by pressing her palm into Anne's and spelling the word "WATER" once again, as if to acknowledge the river of instruction that began at the well pump.

No killings occur before the curtain falls. The narrative ends in the Keller living room where the family accepts the change Anne has wrought: Helen, who began the story as a blind, deaf, mute child given to violent outbursts, has become a girl who can communicate through the manual alphabet. Anne remains the strict, persistent teacher who refuses to be diverted by sentimentality, and the Kellers become a family that reacts to Helen's communication instead of hiding from it. The final image is Anne and Helen sitting together, hands touching, as Helen continues to press letters into Anne's palm and to seek out words from the world she can now name.

What is the ending?

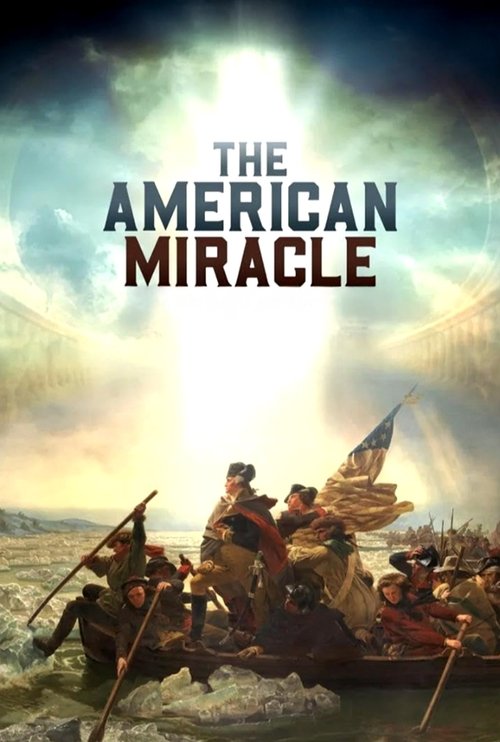

The ending of The American Miracle (2025) depicts the culmination of America's founding as a divine and providential event, emphasizing the miraculous nature of key historical moments and the faith of the Founding Fathers. The film closes with the deaths of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, symbolizing the completion of a providential chapter in American history.

Expanded narrative of the ending scene by scene:

The final sequence begins with a solemn reflection on the 50th anniversary of the United States. The camera focuses on John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, two former presidents and principal architects of the Declaration of Independence, who are shown in their later years. Despite their earlier political rivalry, the film highlights their reconciliation and friendship, underscoring a theme of unity and shared purpose in the nation's founding.

As the day progresses, both Adams and Jefferson send messages to the public celebrating the nation's milestone. Their speeches are portrayed with reverence, emphasizing their belief in America's special providential purpose and the divine guidance that shaped the country. The film visually contrasts their messages with scenes of the American people reflecting on the nation's journey, reinforcing the idea that America's existence is no accident but a miracle.

The narrative then shifts to the poignant moment when both Adams and Jefferson pass away on the same day. This coincidence is presented as a miraculous sign, not mere chance, reinforcing the film's central thesis of divine intervention. The camera lingers on their peaceful faces, symbolizing the end of an era and the fulfillment of their vision for the nation.

Interspersed with these scenes are flashbacks to earlier moments in the film, such as George Washington's leadership during the Revolutionary War, including his immunity to smallpox and the fog that allowed his troops to escape the British at the Battle of Long Island. These flashbacks serve to remind viewers of the many instances of providence that led to America's founding.

The film closes with a narrator's voiceover, reflecting on the ongoing significance of faith, prayer, and divine providence in America's history. The final image is a beam of sunlight shining down, symbolizing God's continued blessing on the nation.

Regarding the fate of the main characters at the end:

-

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson both die on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, their deaths portrayed as a providential event marking the completion of their historic contributions.

-

George Washington is remembered through flashbacks, his legacy as the Father of the Country firmly established, with emphasis on his faith and miraculous protection during the war.

The ending underscores the film's message that America's founding was guided by God's hand, with key figures fulfilling their roles under divine providence, culminating in a symbolic and miraculous closure to the nation's formative chapter.

Is there a post-credit scene?

Yes, the movie The American Miracle (2025) includes a post-credits scene. This scene looks ahead to a sequel, with Michael Medved noting that the American miracle is not concluding with this film, implying continuation of the story or themes in a future installment.

What specific miracles or providential events are depicted in the movie involving George Washington during the War for Independence?

The movie shows a series of providential miracles where George Washington and his troops repeatedly escape destruction during the War for Independence. It also includes a prophecy by a Native American chief in 1770 that Washington cannot be killed in war and would eventually lead a great nation.

How does the film portray the role of prayer and divine intervention at the Constitutional Convention?

The film depicts an impasse at the Constitutional Convention being broken when Benjamin Franklin suggests that the delegates' efforts would fail unless they made God and prayer the central focus, emphasizing the importance of prayer and divine intervention in the founding of the United States.

Which historical figures besides George Washington are prominently featured in the film's reenactments?

Besides George Washington, the film features Benjamin Franklin prominently, especially in the context of the Constitutional Convention. It also includes portrayals of other Founding Fathers involved in the War for Independence and the debates over slavery and equality under the law.

What role does the Native American chief's prophecy play in the narrative?

The Native American chief's prophecy in 1770 is a key plot element, foretelling that George Washington cannot be killed in war and will lead a great nation, which underscores the film's theme of divine providence guiding America's founding.

How are the debates on slavery and equality under the law presented in the movie?

The movie ends with a presentation of the debates at the 1787 Constitutional Convention, including discussions on the issue of slavery and equality under the law, highlighting the complex challenges faced by the Founding Fathers in shaping the new nation.

Is this family friendly?

The movie The American Miracle (2025) is generally family friendly but is best suited for older children and adults due to its length (2 hours 30 minutes) and dense historical content, which may require breaking into shorter segments for younger viewers. It is unrated but contains no sex, nudity, or strong language.

Potentially objectionable or upsetting aspects for children or sensitive viewers include:

- Scenes of warfare with gunfire, explosions, and men wounded or dying.

- Arguments and bitter debates among historical figures, including some rudeness and aggression from British characters.

- A strong Christian, biblical, and patriotic worldview emphasizing Divine Providence, miracles, and prayer, which may not align with all viewers' beliefs and could be sensitive for some.

- Some scenes of people drinking alcohol and one instance of pipe smoking, but no drug use.

There are no obscenities, profanities, or sexual content. The film is primarily a historical documentary with a religious perspective, so the main considerations for family viewing are the war-related visuals and the religious-patriotic themes.