Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

In December 1944, on the island of Palawan in the Philippines, the war has turned against Japan but the cruelty of its occupation burns as fiercely as ever. A group of American prisoners of war, ragged and skeletal after years of captivity, are marched out under the watch of the Kempeitai. The men move slowly, some limping, many barely able to walk. Japanese soldiers order them into a long trench, the prisoners stumbling down into the earth, confused and exhausted. The air is heavy with the smell of gasoline long before anyone understands what is happening.

Cans are carried to the edge of the trench. Liquid splashes down on the men. Eyes widen as the realization dawns: this is not water. Someone whispers hoarsely, "They're going to burn us." Another tries to clamber up, but rifle butts slam him back down. A Japanese officer, calm, methodical, gives a curt order. Torches are thrown.

Flame erupts. The trench becomes an instant inferno as hundreds of men ignite, their uniforms and skin catching fire at once. Screams tear through the night as bodies thrash and claw at the dirt walls. A few manage to scramble up, engulfed in flames, arms flailing. They stagger out, running blindly, human torches racing across the ground. The Japanese gun them down without hesitation, bullets snapping through burning flesh. Men fall, one by one, until all movement stops. Smoke rises. The firelight flickers on expressionless Japanese faces.

Watching the chaos from the edge of the killing ground is a Japanese officer whose name will echo later: Lieutenant Hikobe. His face is impassive, but what he sees here will become his template for what to do when the enemy comes close again: no prisoners, no mercy.

By early 1945, American forces are closing in on the Japanese‑occupied Philippines. News of the Palawan massacre reaches Allied command, spreading horror and fury. In Manila, in jungle camps, in makeshift headquarters, the message is clear: if American troops get too close to any POW camp, the Japanese will likely do again what they did on Palawan. The remaining prisoners--men who survived the Bataan Death March and three brutal years of captivity--are in mortal danger.

At Lingayen Gulf, as the U.S. Army surges back onto Luzon, the 6th Ranger Battalion gathers on a wide, churned‑up beach that still smells of sea salt and cordite. Trucks rumble past, ships sit on the horizon, and fighter planes roar overhead. In a commandeered building serving as a field headquarters, Lieutenant General Walter Krueger unfolds a map over a rough table. He taps a spot inland: Cabanatuan, a notorious Japanese prisoner‑of‑war camp.

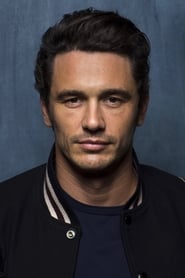

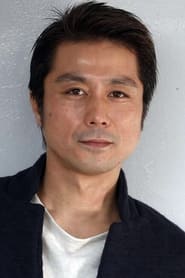

Krueger's eyes settle on Lieutenant Colonel Henry Mucci, commander of the 6th Ranger Battalion. Mucci stands straight, a compact man with a sharp gaze and a carefully trimmed mustache, his khaki uniform immaculate despite the chaos of the front. Krueger explains the situation: more than 500 American POWs are held at Cabanatuan, kept alive through forced labor and starvation, guarded by hardened Japanese troops. After Palawan, intelligence indicates the Japanese are under orders to kill all prisoners rather than let them be liberated.

"This raid," Krueger says, voice low but firm, "is not about taking ground. It won't win the war. But we owe these men a debt. Get them out before the Japanese wipe them out."

The assignment is given: go deep behind enemy lines, thirty miles into territory where Japanese forces outnumber them 100 to 1, reach Cabanatuan, and bring every prisoner back alive. It is, tactically, near‑suicidal. Morally, it is non‑negotiable.

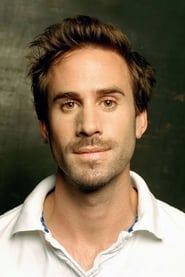

Outside, Mucci assembles his Rangers in the dusty light. A hundred and twenty‑one hand‑picked men form up: lean, fit, trained to an edge but untested under fire. Their faces are young, some barely older than boys. Among them stands Captain Robert Prince, analytical and intense, the battalion's quietly brilliant planner.

Mucci paces before them, his voice carrying: "You are the best‑trained troops in the U.S. Army." The men straighten a little more. Some grin, some swallow. He lets the praise hang for just a moment before adding, implicitly, what they all know: they have never shed blood in combat. Their first real test will be this mission.

Inside the Cabanatuan POW camp, a very different formation of men shuffles into roll call. The camp sprawls near the city of Cabanatuan, a bleak cluster of bamboo barracks ringed by barbed wire, guard towers, and trenches. Around 500 American servicemen--survivors of Bataan and years of abuse--move about in ragged lines, their bodies emaciated, their skin sallow, their eyes sunken. The guards, Kempeitai and regular Japanese troops, are well‑fed, armed, and quick with their fists and rifle butts.

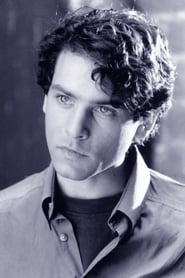

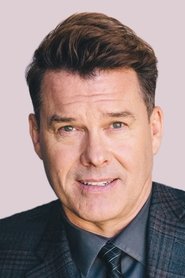

Major Daniel Gibson stands among the prisoners, trying to hold himself upright despite the malaria that ravages him. Fever shakes his thin frame, but his posture, his expression, speaks of command. He is the senior officer among the POWs, and his presence is one of the few things keeping their morale from total collapse. Near him is his friend Major Redding, a man who admits quietly that Gibson is "the only thing keeping me living and sane."

The men are forced out to labor details under the blazing Filipino sun--moving logs, digging ditches, hauling supplies they will never see again in their own mess. At night, under dim bulbs and moonlight, they lie on bamboo slats with bellies gnawing from hunger, scratching lice from their skin, listening to coughs and occasional muffled sobs.

On one grim afternoon, a prisoner is marched in front of the assembled men, caned savagely, then hanged as an example. His body dangles, motionless, for days, a stark reminder that discipline here is maintained by death and terror. The corpse appears in multiple scenes, the unspoken threat always hanging over the prisoners' heads.

Over all of this presides Lieutenant Hikobe, now a ranking Japanese officer at Cabanatuan. His demeanor is controlled, his intelligence obvious, his cruelty measured rather than wild. His bushido‑instilled contempt for surrendering enemies is absolute. As American forces draw nearer and rumors ripple through the camp, Hikobe receives orders consistent with Palawan: at the first sign of American breakthrough, he is to ensure no prisoners survive.

Outside the wire, the war has many faces. In Manila and surrounding towns, an underground network of resistance fighters and sympathizers moves quietly under the eyes of the occupiers. Among them is Margaret Utinsky, an American nurse living under an assumed identity. She works in hospitals and clinics, but her true vocation is risk: smuggling medicine, food, and information to prisoners and guerrillas, coordinating with Filipinos and other foreigners determined to defy Japanese rule.

Margaret moves through streets patrolled by Japanese soldiers, her posture calm, her documents in order, her bag carrying contraband that could get her killed. She meets informants in shadowed corners, passes notes folded into hymnals, and hides fugitives in church basements. On two occasions, when the Kempeitai close in, she and her associates take refuge in churches. Priests usher them into side chapels and crypts, quietly sheltering them. One priest tells her in a hushed voice, "You have to trust in something stronger than yourself." She nods, though the strain lines her face.

She knows about Cabanatuan. She knows about the hunger and disease and torture. She knows, too, about Major Daniel Gibson, though the film hints more at their emotional connection than spells it out. She sends medicine toward the camp whenever she can, knowing that perhaps, just perhaps, these small vials and tablets are the thin line keeping Gibson upright.

As American troops land on Luzon and push inland, Margaret's underground work becomes both more hopeful and more perilous. Japanese patrols sweep harder, arrests increase, and the penalty for aiding the enemy remains death.

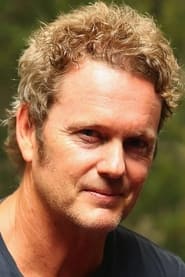

Back at Lingayen Gulf, after receiving Krueger's orders, Henry Mucci turns to Captain Robert Prince. Prince is to devise the operational plan and lead the raid itself. They study maps: the route to Cabanatuan, the positions of Japanese units, the rivers, the rice paddies, the villages. The camp is held by roughly 200 battle‑hardened Japanese soldiers. The surrounding area teems with enemy troops and armor. They will be a tiny force--121 Rangers--moving thirty miles behind enemy lines. The odds are absurd.

Prince lays out the arithmetic: "The area's crawling with them. We're outnumbered a hundred to one." Mucci listens, then responds with something that will echo later: "It isn't always about the arithmetic… sometimes you gotta rely on faith."

The plan takes shape. They will link up with local Filipino guerrillas led by Captain Juan Pajota, who knows the terrain and enemy movement. Filipino fighters will cut telephone lines to Cabanatuan to isolate the camp. They will also ambush a nearby battalion of the Imperial Japanese Army, preventing reinforcements from reaching the camp during the raid. The Rangers themselves will conduct the direct assault on the camp, relying on surprise, precision, and the cover of night.

Prince refines details. He identifies a field south of the camp--a wide, open expanse of grass crossed by a shallow ditch. It is death to cross in daylight under the guns of the guard towers. Yet to get close enough unseen, the Rangers must do exactly that, creeping across to the ditch before sunset and lying motionless until darkness falls. If they are spotted, the mission--and likely the prisoners--are lost.

The date is set: Mucci will lead his 121 Rangers out on the evening of January 27, 1945. They will trek for two days, infiltrate Japanese lines, coordinate with Pajota's men, and launch their multi‑pronged assault on the night of January 30.

In the jungle, the Rangers move out as ordered, leaving the relative safety of American lines. The column snakes along narrow trails through dense foliage. Sweat drenches uniforms. Leeches attach to ankles and calves. Every snapped twig sounds like a shot. Scouts range ahead and to the flanks, eyes scanning for patrols and roadblocks. The night brings swarms of insects and the distant rumble of artillery. At any moment, they know, they could stumble into a Japanese company and be wiped out.

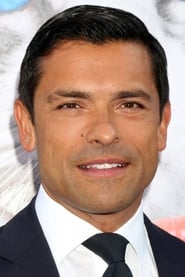

On the second day, in a clearing on the edge of a village, they finally meet Captain Juan Pajota and his Filipino guerrillas. Pajota is lean, hardened, his men carrying a mix of American and captured Japanese weapons. Their faces are a mix of youth and age, united by stubborn resolve. Some are in tattered civilian clothes, others in bits and pieces of uniforms. They greet the Rangers with cautious respect.

Juan and Mucci clasp hands, two commanders with different accents but a common enemy. Pajota explains the local situation: Japanese patrols move along the main road, a Japanese battalion is encamped not far from the camp, and bridges over nearby rivers are key chokepoints. He and his men know the paths, the blind spots, the habits of the occupying forces. Without them, the Rangers would be walking blind.

Prince details his integrated plan to Pajota. The Filipino guerrillas will first cut all telephone lines leading out of Cabanatuan, isolating the camp from rapid communication. They will then set an ambush on the road, engaging the Japanese battalion when it attempts to respond to the commotion at the camp. Additional guerrilla elements will be tasked with blowing a critical bridge to stop or delay any reinforcements and with gathering local carabao carts for transporting the weakened POWs once freed.

Pajota listens, nodding. "We can do this," he says quietly. "But once we start, there is no turning back."

Meanwhile, inside Cabanatuan, Major Daniel Gibson continues his daily fight against despair and disease. Malaria racks him with chills and fevers, but he refuses to succumb. He encourages the men, keeps order, negotiates with the guards when he can to lessen punishments or secure the smallest concessions. To the men, he is a steady presence, a symbol that someone still cares about discipline, dignity, and hope.

Rumors reach the camp--whispered through new arrivals, snatches from guards--that American forces are back in Luzon, that planes bearing white stars have been seen in the sky. These stories are fragile, easily crushed by another beating or another corpse swinging as a warning. Still, they kindle something in the prisoners' gaunt faces.

In Manila and its environs, Margaret Utinsky continues her clandestine work. At one point, she and several members of the underground are forced to flee into a church to escape a sweep. Japanese soldiers shout outside; inside, a priest hurries them behind the altar and down into a cool, stone crypt. As they listen to boots thumping above, Margaret's breathing is shallow but composed. The priest's earlier words--"You have to trust in something stronger than yourself"--linger in the air.

The film hints at her emotional bond with the men she helps, especially Major Gibson. She reads names of prisoners and missing soldiers, her finger tracing the paper, eyes lingering on his. She fights not only against the Japanese, but against the cruel possibility that all her efforts will be for nothing if the POWs are executed before rescue can arrive.

As January 30 approaches, tension winds tighter. The Rangers and Pajota's men edge closer to Cabanatuan, moving cautiously, using cover, avoiding main roads. They spy on the camp from a distance, noting guard rotations, tower positions, and the layout of the barracks. They observe that the camp is heavily guarded, with roughly 200 Japanese troops inside--battle‑hardened, disciplined, deadly.

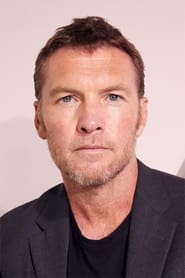

Prince refines timing. Mucci approves the final sequence. Units are assigned specific roles: some will approach the main gate, others will attack secondary entrances and guard towers, a demolition team will target vehicles and armored assets, and sharpshooters will neutralize key positions. Among the Rangers are Altridge and Lucas, designated to go after the Japanese trucks and tanks inside the camp, and Riley, a capable fighter who will play a crucial role later.

The day of the raid, the Rangers reach the southern approach to the camp and confront the open field--hundreds of yards of low grass, fully exposed to watchful Japanese eyes in the guard towers. The sun is still up, the light unforgiving. Yet this is the only way to get close enough for a coordinated assault.

They flatten themselves against the earth and begin to crawl. Hours pass as they inch forward, yards at a time, sweat soaking their uniforms, fingers digging into the soil. Any sudden movement, any glint of metal, could draw a bullet or, worse, trigger an order to slaughter the prisoners. The distant figures in the towers seem to loom over them, rifles slung casually, eyes scanning intermittently.

At last, they reach the shallow ditch at the edge of the field. They slide down into it, pressed together in the narrow trench, weapons cradled, hearts pounding. Above them, the sky moves from afternoon blue to dusk and then to darkness. Insects hum. Their muscles cramp from stillness. They dare not light cigarettes, dare not whisper. Somewhere in the camp, a prisoner coughs; somewhere else, a guard laughs.

Simultaneously, Pajota and his guerrillas execute their part of the plan. Filipino fighters move along poles and trees, cutting telephone lines that run from the camp out toward Japanese headquarters. Wire falls silently in the dark. Another team advances toward a bridge that constitutes a critical crossing for any Japanese reinforcements. They set charges, working by feel, fingers fumbling with fuses.

When the charges detonate, the bridge erupts in a column of flame and debris. Planks and girders rain into the river below. The explosion roars across the night, announcing that, for a critical window, the road is severed. Japanese soldiers at a nearby battalion camp scramble out, shouting, some trying to determine whether this is an accident or attack.

Juan Pajota orders his men into position along the roadside and in the tree line, preparing the ambush that will follow. The tension in their faces mirrors that of the Rangers lying in the ditch: they all know that if they fail to hold the Japanese battalion, hundreds of American POWs will die.

Darkness settles fully. Inside Cabanatuan, Lieutenant Hikobe senses the enemy's proximity. Whether through reports of explosions or the distant glow on the horizon, he understands the risk. The memory of Palawan is with him; he knows what the Japanese command expects if rescue seems imminent. He moves to implement his own version of that brutal precedent: he orders preparations to kill the prisoners en masse if necessary. His men check mortars, machine guns, and rifles.

Back in the ditch, Captain Robert Prince checks his watch. The time has come. He gives a low signal. Rangers rise from the shallow depression, spreading out, weapons ready. They move toward the camp slowly at first, then more swiftly as they pass beyond the sweep of the towers' most obvious sight lines. The night, thick and close, shields them.

At a prearranged moment, American aircraft roar overhead, distracting Japanese eyes upward. Rangers surge forward. At the perimeter of the camp, they cut through the barbed wire, slipping inside the compound. The raid begins.

They hit the guard towers first. Silenced shots and sudden bursts of fire drop sentries before they can sound the alarm. The Rangers sprint between buildings, hugging shadows, their movements rehearsed in their minds a hundred times. When the first loud shots crack through the air, chaos erupts.

Japanese guards scramble, shouting, firing blindly. Rangers return fire with deadly accuracy, mowing down camp guards. The Kempeitai, caught off guard, are cut down in clusters. Grenades explode near barracks and guard posts, shredding wood and flesh. Some Japanese soldiers barely get their rifles to their shoulders before bullets punch them backward.

Inside the barracks, the POWs are jerked awake by the gunfire and explosions. Panic surges; some think the Japanese have begun the massacre they have long feared. Major Daniel Gibson staggers to his feet, feverish but commanding. He tries to calm the men--"Stay low! Stay down!"--even as dust rains from the ceiling and splinters fly.

Rangers burst into the barracks, silhouetted in doorways. One shouts, "We're Americans! We're here to get you out!" For a split second, there is stunned silence--could this be real?--and then an explosion of emotion. Men weep, laugh, cry, some too weak to stand, reaching out to touch the rescuers. Gibson, eyes wide with disbelief and gratitude, helps organize the evacuation, pushing men toward the exits.

Across the camp, Altridge and Lucas sprint toward the motor pool and vehicle park, where Japanese trucks and tanks are parked. Their orders are clear: deny the enemy the use of armor and transport. They slam charges onto fuel tanks and undercarriages, light fuses, and dive behind cover. A series of explosions ripples through the motor pool. Trucks buck and twist; tanks are immobilized, their tracks blown off, some hulls catching fire. Flames leap into the night sky, casting a hellish orange light over the camp.

Near the artillery positions, Lieutenant Hikobe reacts to the attack not with panic but with deadly purpose. He understands that if he cannot hold the camp, he can still deny the Americans their objective by killing the prisoners. He orders his men to aim mortars at the barracks and begins directing fire that, if unleashed, will obliterate the POWs, rescuers and all.

Hikobe moves among his gunners, shouting orders. One of his mortars thumps, sending a round whooshing overhead. It lands near the camp, spraying fragments. Rangers recognize immediately the existential threat: if those mortars continue to fire, hundreds of men will die in an instant.

Riley, one of the Rangers, sees Hikobe's position and understands the stakes. While others trade fire with scattered Japanese resistors, Riley begins a flanking maneuver, using cover and darkness to get behind the mortar position. Bullets snap past him. He ducks, rolls, advances, eyes fixed on the silhouette of the Japanese officer coordinating the slaughter.

At the same time, at the perimeter beyond the camp, Juan Pajota's ambush is sprung. The Japanese battalion, alerted by explosions and rising flames, moves along the road in trucks and on foot, heading toward Cabanatuan. As they reach Pajota's kill zone, Filipino guerrillas open fire from the trees and ditches. The first volley shreds the front of the column, killing drivers, shattering windshields, flipping trucks into ditches. Japanese soldiers tumble out, returning fire.

A fierce firefight erupts. Muzzle flashes rip the darkness. Men shout in Tagalog and Japanese. Filipino fighters, outnumbered but dug in, reload and fire, mow down enemy troops, and toss grenades into clustered formations. The Japanese battalion tries to push through but runs into more mines, more ambush points. Bodies pile by the roadside. Pajota moves among his men, shouting encouragement, directing fire, adjusting positions to maintain the deadly crossfire.

Japanese casualties mount. Nearly 800 Japanese soldiers will die this night between the camp and the surrounding battle, most of them in the surprise attack and ambushes. For many, their killers are faceless figures in the dark--Rangers and guerrillas executing a plan with ruthless efficiency.

Back inside Cabanatuan, the Rangers are now moving the POWs out of their barracks, rushing them toward the exits and the waiting carabao carts outside the perimeter. Some prisoners try to run under their own power, but their legs buckle after a few steps. Others are carried fireman‑style over Rangers' shoulders. Still others are guided, two men supporting a third.

Mucci moves through the camp, directing teams, making sure the flanks are secure and guarding the route out. He remains near Pajota's sector as well, concerned about protecting the flank of the guerrillas who are holding back the Japanese battalion. His role shifts from commander in a war room to a front‑line leader, checking that no one is left behind, that no gap opens in their defensive ring.

In the officer's mess, a small team of Rangers bursts in and stops in shock. The room is full of provisions: sacks of rice, canned goods, preserved foods piled high. The discovery hits them with a sickening realization. While the prisoners outside wasted away, their bodies ravaged by malnutrition, the Japanese officers sat on ample food stores, deliberately starving the men under their control. It is a quiet but enraging revelation: this cruelty was not just neglect, but policy.

Riley finally reaches the flank of Lieutenant Hikobe's mortar position. He sees the Japanese officer, partly lit by the flicker of explosions, barking orders, moving with cold precision. A mortar pops again, a shell launching into the night. Riley knows the next one could land in a barracks full of prisoners just now getting to safety.

He charges. A Japanese soldier in his path swings a rifle; Riley dodges, slams the man to the ground, and keeps going. He collides with Hikobe, and the two men crash into the dirt, a tangle of limbs and weapons. They fight hand‑to‑hand in the din--punches, elbows, desperate grappling. Hikobe reaches for his sidearm; Riley grabs his wrist. They roll. The pistol skitters, then is snatched again.

With a surge of strength fueled by the knowledge of what is at stake, Riley wrests control of Hikobe's own gun and turns it on him. For a moment, their faces are inches apart: Hikobe's eyes flare with hatred and perhaps a flash of understanding that his brand of bushido has led him here, to this ditch, under the barrel of his own weapon. Riley pulls the trigger. The shot cracks. Lieutenant Hikobe jerks and goes limp, the bullet from his own gun ending his life.

Hikobe's death is both quiet and monumental. With him gone, the focused effort to bring mortar fire onto the prisoners collapses. Surviving Japanese gunners are confused, some killed in quick follow‑up shots. The threat of mass death from above is blunted.

Throughout the camp and fields, Rangers finish mopping up resistance. Japanese camp guards are killed almost to a man; those who try to flee are cut down. The Kempeitai, brutal enforcers of misery for years, meet swift ends in the confusion and fury of the raid. Inside the camp, there will be no organized counterattack; outside, the remnants of the battalion harried by Pajota's men are in tatters.

As fires burn in the motor pool and structures crackle, Captain Prince realizes the primary objective is nearly complete. All remaining prisoners--511 POWs in total--have been located and are in the process of being evacuated. He reaches into his gear, pulls out a flare gun, and aims it into the night sky above the camp. He squeezes the trigger.

A red flare shoots upward, hissing, then bursts overhead, casting the scene in an eerie crimson glow. For the Rangers and guerrillas, this is the long‑planned signal: the raid is complete; fall back to the rendezvous. For Japanese forces in the distance, it may be just one more confusing light in a battlefield gone mad.

The prisoners are loaded into carabao carts and onto makeshift litters. Villagers, summoned by Pajota's guerrillas, bring their animals and wagons, doing what they can to assist in the exfiltration. Some POWs insist on walking, clutching rifles given to them by Rangers, determined to contribute however they can. Others can barely lift their heads.

They move out from the camp, leaving behind fires, shattered towers, and Japanese corpses. Two American Rangers lie dead--killed during the assault, their names honored in the end credits even if the film does not dwell on them individually. Twenty‑one Filipino fighters have also fallen in the ambushes and firefights, paying with their lives for the liberation of men they have never met. Their deaths occur in quick, brutal flashes: a guerrilla hit by machine‑gun fire at the roadside, another blown apart by a grenade, a Ranger shot while crossing open ground. They die where they fall, their bodies left temporarily in places that will later be reclaimed or forgotten, but their sacrifice is woven into the larger success.

The column of survivors--Rangers, prisoners, guerrillas, villagers--threads back through the countryside. The night is long. Japanese patrols might still appear; aircraft might spot them at dawn. Yet with every mile they put between themselves and Cabanatuan, the balance tips slightly more toward survival.

They reach the small village of Platero, their planned rendezvous. The village, normally quiet, becomes a makeshift field hospital and staging area. POWs are laid out under trees and in huts. Locals bring water and rice, their faces a mix of curiosity, compassion, and pride. Rangers check weapons, tend to their own wounded, and rest in snatches, still keyed to the possibility of pursuit.

Mucci and Prince move among the men, checking on the prisoners, shaking hands, offering words of reassurance. Some of the rescued soldiers, their voices cracked, offer salutes or choked thanks. Others simply lie there, staring at the stars or the hut ceilings, grappling with the reality that they are no longer prisoners.

From Platero, the combined groups push onward toward Talavera, where the American frontline lies. The journey continues over rough roads and through fields. The weakest of the POWs are barely hanging on; years of starvation and disease mean that even rescue does not magically restore strength. Medics move from cart to cart, checking pulses, trying to keep fevers down, offering sips of water.

At the American lines near Talavera, the sight of the returning column creates an emotional shock wave. Soldiers at the front, dirty and battle‑weary, watch as the carts roll in and gaunt men climb or are lifted out. Cheers erupt. Some men remove their helmets, stunned by the sight of comrades thought lost years ago. Generals and medics converge, orders barked for triage and transport to rear hospitals.

Major Daniel Gibson is carried into the safety of Talavera, but his body has been pushed past its limit. Malaria, malnutrition, and the exertion of the escape weigh heavily. Medics treat him as best they can, but there is only so much to be done with a body so ravaged. In a quiet area, away from the main bustle, he lies on a cot. His breathing is shallow. A friend sits beside him, perhaps Major Redding or another officer, watching helplessly.

Gibson's eyes flicker, as if he is seeing faces that are not there: the men he led, the nurse who smuggled medicines to him from afar, the country he swore to serve. He never makes it to a full rear‑area hospital, never reaches Manila where Margaret Utinsky continues her dangerous work. Before he can be reunited with her, before she can see with her own eyes that he was saved, he slips away. Major Daniel Gibson dies the night after reaching American lines, succumbing to his illness at last. His rescue came in time to free him from the camp, but not in time to save his life.

His death is one of the quiet tragedies that temper the triumph of the raid. For Margaret, who will learn of his fate later, it is a blow that underscores how thin the margin was, how no amount of courage could guarantee survival after such prolonged suffering.

In the days that follow, as the liberated POWs are transported to hospitals and eventually home, the story of the raid spreads. The numbers, when tallied, are stark and almost unbelievable: 511 prisoners rescued from Cabanatuan; nearly 800 Japanese soldiers killed in the surprise attacks on the camp and the ambushed battalion; only two American soldiers lost during the operation; 21 Filipino guerrillas killed while holding back superior enemy forces and ensuring the rescue could proceed.

For Margaret Utinsky, the war ends with a mixture of personal grief and public recognition. Her clandestine efforts, her willingness to risk torture and execution to smuggle supplies and aid the underground, do not go unnoticed by the highest levels of the U.S. government. After the war, she stands in Washington, D.C., in a formal setting far removed from the cramped church crypts and dark alleys of occupied Manila. President Harry S. Truman himself presents her with the Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian decoration for service and valor. The citation recognizes her courage and persistence under occupation, her contribution to the survival of POWs and the effectiveness of the resistance.

Henry Mucci and Robert Prince also receive recognition. The rescue raid at Cabanatuan, once a desperate long‑shot mission, becomes known as one of the most audacious and successful special operations of World War II. For their leadership and bravery, Mucci and Prince are awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the second‑highest military decoration that can be given to a member of the United States Army. The medals acknowledge not just their planning and command, but their willingness to lead men into overwhelming odds for a purpose that was, as some observers note, more about mercy than strategy.

The film closes by tying these dramatized events back to the historical record. On screen, text confirms the casualty figures and rescue numbers: 511 American POWs freed, nearly 800 Japanese killed, only two Americans and 21 Filipinos lost in the raid. It affirms that the story the audience has watched is grounded in real history, that the faces and names--Henry Mucci, Robert Prince, Daniel Gibson, Margaret Utinsky, Juan Pajota, Lieutenant Hikobe, and the unnamed Rangers, guerrillas, and prisoners--represent real people and real sacrifices.

The final images juxtapose the weary but defiant faces of the rescued POWs with the honors later bestowed on those who risked everything to bring them home. The rescue at Cabanatuan stands not as a turning point in the grand strategy of the Pacific Theater, but as a testament to the lengths soldiers and civilians will go to save their own, to redeem, if only partially, the earlier abandonment of those who endured the Bataan Death March and years of brutal captivity.

The story ends not with a single triumphant moment, but with a complex resolution: a successful raid, the deaths of friend and foe, the survival of hundreds, and the knowledge that even in war, where arithmetic and odds dominate planning, faith, courage, and a refusal to leave men behind can reshape what is possible.

What is the ending?

In the ending of "The Great Raid," the American forces successfully execute their mission to rescue the prisoners of war from the Japanese camp at Cabanatuan. The raid is intense and fraught with danger, but ultimately, the soldiers manage to free the captives and lead them to safety. The film concludes with a sense of triumph and relief as the survivors are reunited with their loved ones.

As the climax of "The Great Raid" unfolds, the scene shifts to the night of the raid. The American soldiers, led by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Mucci and Captain Robert Prince, stealthily approach the Cabanatuan prison camp. The atmosphere is thick with tension; the air is heavy with the weight of their mission and the lives at stake. The soldiers are determined, their faces set with resolve, knowing that they are not just fighting for their own comrades but for the lives of the prisoners who have suffered immensely.

As they infiltrate the camp, the soldiers move with precision, their hearts pounding in their chests. They encounter Japanese guards, and the tension escalates as they engage in a series of skirmishes. The sound of gunfire echoes through the night, and the soldiers' adrenaline surges as they push forward, driven by the hope of rescuing the captives. Each soldier is acutely aware of the stakes; failure could mean death for the prisoners and themselves.

Inside the camp, the prisoners, emaciated and weary, are taken by surprise as the Americans burst in. The sight of their liberators ignites a flicker of hope in their eyes, a stark contrast to the despair they have endured. The soldiers quickly work to free the prisoners, cutting through the chains that bind them. The emotional weight of the moment is palpable; tears of joy and disbelief flow as the captives realize they are being rescued.

As the raid progresses, the urgency intensifies. The Japanese forces begin to regroup, and the Americans must act quickly to evacuate the prisoners. The scene is chaotic, filled with the sounds of gunfire and the cries of the wounded. Lieutenant Colonel Mucci and Captain Prince coordinate the retreat, ensuring that as many prisoners as possible make it out alive. The camaraderie among the soldiers is evident; they are fighting not just for their mission but for each other and the lives they are saving.

In a heart-stopping moment, the group faces a near-fatal encounter with a Japanese patrol. The soldiers display incredible bravery, covering each other as they fend off the attackers. The tension is thick as they navigate through the camp, the shadows of the night providing both cover and danger. The emotional stakes are high; each soldier is acutely aware that their actions could mean life or death for the prisoners.

As they finally reach the extraction point, the soldiers and the rescued prisoners are met with a mix of relief and fear. The sound of approaching Japanese reinforcements looms, and the urgency to escape is palpable. The Americans rally together, helping the weak and injured among the prisoners. The scene is filled with a sense of urgency and desperation, but also a profound sense of hope as they make their way to safety.

In the final moments of the raid, the group successfully reaches the extraction point, where they are met by American forces. The sight of the helicopters and the promise of safety brings tears to the eyes of the rescued prisoners. The soldiers share a moment of triumph, their faces reflecting the relief and joy of their successful mission.

As the film concludes, we see the aftermath of the raid. The rescued prisoners are reunited with their families, their faces filled with gratitude and relief. Lieutenant Colonel Mucci and Captain Prince stand together, reflecting on the success of their mission and the lives they have saved. The emotional weight of their journey is evident; they have faced insurmountable odds and emerged victorious.

The fate of the main characters is one of survival and triumph. Lieutenant Colonel Mucci and Captain Prince return as heroes, their bravery celebrated. The rescued prisoners, once broken and hopeless, are given a second chance at life, their spirits lifted by the courage of their liberators. The film closes on a note of hope, emphasizing the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity.

Is there a post-credit scene?

The Great Raid, produced in 2005, does not have a post-credit scene. The film concludes after the main narrative, which focuses on the daring rescue of American prisoners of war from a Japanese camp during World War II. The story wraps up with the successful execution of the raid and the emotional reunions of the soldiers and their families, leaving no additional scenes or content after the credits.

Is this family friendly?

"The Great Raid," produced in 2005, is a war film that depicts the harrowing events of a World War II rescue mission. While it is a historical narrative, it contains several elements that may be objectionable or upsetting for children or sensitive viewers.

-

Violence and Combat Scenes: The film features intense battle sequences, including gunfire, explosions, and hand-to-hand combat. These scenes can be graphic and may evoke strong emotional reactions.

-

Prisoner Treatment: There are depictions of prisoners of war suffering from malnutrition, illness, and harsh treatment by their captors. This portrayal can be distressing, especially for younger viewers.

-

Death and Loss: Characters experience significant loss, and there are moments of death that are portrayed with emotional weight, which may be upsetting.

-

Emotional Trauma: The film explores themes of fear, despair, and the psychological impact of war on soldiers and prisoners, which may be difficult for sensitive viewers to process.

-

Historical Context: The backdrop of World War II and the atrocities committed during this time may be challenging for children to understand fully, leading to potential confusion or distress.

Overall, while "The Great Raid" is a compelling story of bravery and sacrifice, its mature themes and intense scenes may not be suitable for all audiences, particularly younger children.