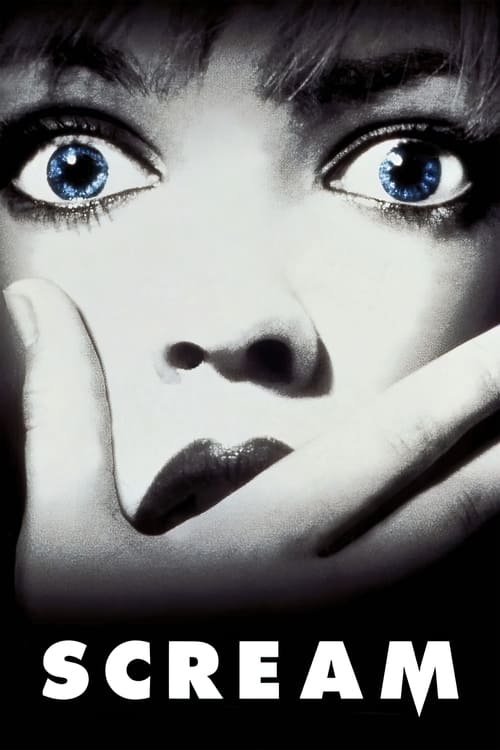

Ask Your Own Question

What is the plot?

Night falls over the quiet, tree‑lined streets of Woodsboro, California, and a big, comfortable suburban house glows warmly against the dark. Inside, high‑school student Casey Becker tends to a bag of popcorn on the stove, the kernels beginning to rattle softly as they heat. She moves around the bright kitchen in an oversized cream sweater, blonde hair loose, the house empty, the television ready for a horror movie marathon.

The phone rings.

Casey answers with a cheerful, casual "Hello?" expecting a friend. The voice on the other end is male, deep and slightly playful, unfamiliar but smooth. He says he must have dialed the wrong number. She brushes it off and hangs up. The popcorn hisses. The phone rings again. She laughs, picks up, and this time the stranger lingers, chatting, flirting, asking what she's doing, what she's watching. They drift naturally into talking about horror movies--Halloween, A Nightmare on Elm Street, the familiar titles any teen would know.

"Do you like scary movies?" he asks, the question both teasing and oddly intimate.

Casey smiles, leaning on the counter, wrapping the phone cord in her fingers. She does, she tells him. She names Halloween as one of her favorites, mentions Freddy Krueger. The conversation should be harmless, but there's a slight edge in his tone now. He wants to know her name. She jokes that he doesn't need it. He replies, quietly, "I want to know who I'm looking at."

The words hit her like a slap. Her smile fades. She turns toward the sliding glass door, the black backyard pressing against the glass. The popcorn bag on the stove has started to swell, forgotten.

She tries to shake it off. Maybe it's a joke. But the voice loses its flirtatious warmth. He becomes angry when she tries to hang up, threatening. He asks if she has a boyfriend. She lies: yes, he's big and he'll be here any minute. The caller instantly undercuts the lie. He tells her her boyfriend is already here, and orders her, in a low, deadly voice, to turn on the patio lights.

Casey steps to the wall and flips the switch. Floodlights snap on, harsh and white. On the stone back patio, in a patio chair, sits Steve Orth, her real boyfriend, bound and gagged in his letterman jacket, eyes wild with terror. Duct tape seals his mouth. Rope digs into his wrists. Casey's breath catches in her throat, a strangled whimper rising.

The man on the phone explains the rules. They're going to play a game: horror‑movie trivia. Answer right and Steve lives. Answer wrong… The camera of the night presses in, the wind hissing in the trees, the popcorn now burning, the bag swelling and blackening over an open flame.

He tests her with easy questions, building tension, building false confidence. "Who's the killer in Halloween?" she answers: Michael Myers. Correct. Then he asks about Friday the 13th: "Who was the killer in Friday the 13th?" She responds quickly: Jason. He savors the moment before telling her she's wrong--Jason isn't the killer in the first film; his mother is. She screams that she saw the movie. He tells her she should have paid closer attention.

The patio lights go out, plunging Steve back into darkness. There's a muffled, guttural sound, and when the lights flick on again, Steve's throat is slashed open, his chest and abdomen carved and bloody, his body twitching in the chair before going still. Casey begins to sob, the phone slick in her hands.

The caller stops playing.

He tells her he wants to know who she is. He tells her she should not have hung up on him. He tells her if she runs, he will get her. Then a chair crashes through the glass door. A figure in a long black robe and a white, elongated mask--a screaming, distorted face--steps into the house, a large hunting knife gleaming in his hand.

Casey bolts. The house that felt cozy seconds ago becomes a maze of blind corners and vulnerable windows. She grabs a kitchen knife, crouches, tries to slip past him. The masked figure is fast, relentless. He lunges, the knife flashing, slashing into her chest and side. She crashes through furniture, gasping, staggering, leaving smeared handprints of blood on walls and doorframes.

Outside, headlights sweep into the driveway. Her parents are home.

Casey, throat damaged by a stab, cannot form a full scream. She crawls across the grass toward them, fingers clawing at the earth. Inside the house, the phone rings again. Her mother answers and hears gurgling, wet choking noises--her daughter dying on the line. Outside, the killer stands over Casey and drives the knife into her again and again, finishing the work with vicious, efficient movements.

Moments later, her parents call out her name, run through the ransacked house, panic rising. Her father orders his wife to go to the neighbors and call the police. She steps outside, eyes scanning the yard, and stops in a strangled, keening cry. Hanging from a large tree in the front yard, Casey's body dangles, gutted, intestines spilling, her face frozen in a silent scream. The Ghostface killer has made an unforgettable tableau.

Woodsboro wakes up screaming.

The next day, the town buzzes with the news of two dead teenagers on the outskirts of suburbia. Police cars ring the Becker house. TV vans swarm, satellite dishes pointed skyward. The murders are stranger‑than‑fiction, and the national media tastes blood.

Elsewhere in town, in a cozy, slightly cluttered hilltop home, Sidney Prescott sits at the desk in her bedroom, typing on her computer. She's a high‑school student too, but there is a different heaviness about her. On her wall is a framed photograph of her mother, Maureen Prescott, who was murdered about a year earlier. Sidney's father, Neil Prescott, is getting ready to leave on a business trip; he will be out of town over the coming weekend. When he kisses Sidney goodbye and leaves, the already quiet house becomes more hollow.

The bedroom window rattles, and Billy Loomis climbs in from a nearby tree branch. Billy has dark hair, a slightly brooding face, and the casual confidence of a long‑time boyfriend. Sidney is surprised and flustered; her father doesn't like boys in her room. Billy speaks softly about how he just wanted to see her. The TV in the background plays a horror scene. Billy mentions how their relationship changed after Maureen's murder--how they went from hot and heavy to something more restrained. He complains that they've "edited" their relationship from an NC‑17 rating to a PG‑13. Sidney jokes, briefly lifting her shirt and flashing him, taking back a little control, but the conversation underlines the trauma lodged between them.

News of Casey Becker and Steve Orth's murders spreads quickly. At Woodsboro High School the next day, students cluster in knots on the lawn and hallways, whispering, sharing gory details with an excitement that is part fear, part morbid thrill. Sidney walks across campus with her best friend, Tatum Riley, a sharp‑tongued, stylish girl with a playful swagger. Tatum promises to pick Sidney up later that evening so Sidney doesn't have to be alone.

In the courtyard, they join Stu Macher, Tatum's exuberant, slightly manic boyfriend, and Randy Meeks, their friend who works at a video store and speaks the language of horror films like it's his native tongue. Stu jokes crudely about the murders, noting that Casey used to date him before she dumped him for Steve. Randy weighs in with a running commentary on "whodunit" motives while referencing slasher tropes. The conversation is both disturbing and darkly funny--they treat real deaths like scenes in the movies they grew up watching.

Police presence around the school ramps up. Deputy Dwight "Dewey" Riley, Tatum's older brother, is a young deputy at the Woodsboro Sheriff's Department, earnest and a bit awkward, trying hard to look authoritative. Inside, Principal Arthur Himbry summons students to his office, raging about how the tragedy will be handled and threatening discipline for anyone joking about it.

Outside the school, news vans congregate. Among them is Gale Weathers, a hard‑edged, ambitious television reporter with perfectly styled hair and a practiced on‑camera smile. She's already famous for her book about the murder of Maureen Prescott, a book that argues the man convicted for Maureen's death, Cotton Weary, is innocent. Gale smells a new story, a follow‑up, maybe even vindication. She pushes her cameraman, Kenny, to get better shots of grieving teenagers and harried cops.

As day bleeds into evening, the town's nerves fray. Sidney goes home to her empty hilltop house, expecting Tatum later. She settles in to watch TV, trying to push down the memories of her mother's murder that this new violence has stirred. The house around her is quiet, the sky outside deepening. Then the phone rings.

Sidney answers, expecting Tatum. The male voice on the line is familiar to the audience now--a modulated, slightly amused tone that hides cruelty. He banters with her, at first pretending to be a friend. When she asks who this is, he says, "Just a guy, interested in knowing who I'm looking at." The same line he used on Casey.

Unlike Casey, Sidney doesn't freak out immediately. She thinks it might be Randy playing a tasteless joke, since he's obsessed with scary movies. She laughs it off, but the caller keeps pushing. He asks about her mother. He makes lewd comments. His words sharpen and cut. Her teasing slowly drains away as she realizes he can see her.

She steps to the front door and opens it, staring out at the empty porch and the dark beyond. "Can you see me right now?" she calls, trying to spot a hiding place. The voice tells her to look out on the porch. She does. Nothing. The night is just night. She calls his bluff, mocking him, then tells him she's not scared because she doesn't "watch that shit" horror movies--life is scary enough, she says, she doesn't need to watch manufactured terror.

Suddenly, the killer's tone shifts. He tells her if she hangs up, she'll die just like her mother. An icy dread slides through her. She backs up. She closes the door. Then he appears.

The Ghostface figure bursts into view inside the house, robe sweeping, knife gleaming, the white mask an exaggerated scream. He charges at her down the hallway. Sidney bolts up the stairs, barely staying ahead of him. Her bedroom, a sanctuary, becomes a barricade. She slams the door, then shoves her closet door open so that it wedges against the bedroom door--a trick we realize she's used before, turning her own room into a temporary safe room.

The knob rattles violently as Ghostface tries to break in. Sidney, shaking, doesn't dare use the phone--it's dead, the line compromised. Instead, she scrambles to her computer, opens a TTY application designed for the hearing‑impaired, and types frantically to 911, calling for help through the modem. On the other side of the door, the killer pounds and claws but cannot break her makeshift barricade.

Just as the pounding stops and the house falls unnervingly silent, the bedroom window creaks open. Billy Loomis appears, climbing in again, breathless and concerned. Sidney, still shaking, collapses into his arms. Then something small and plastic falls from his pocket to the carpet: a cellphone.

In 1996, not every high‑school student carries a cellphone. To Sidney, after being terrorized by phone calls, this detail feels huge. Her eyes sharpen. Paranoia spikes. She pulls away from Billy, suspicion twisting through her features. She runs from the room, down the stairs. Outside, police cruisers are pulling up, sirens low. Dewey arrives with other officers. Sidney shouts that the killer is in the house. Dewey enters with weapon drawn, but the Ghostface costume is gone. All they find is Billy, now in custody, and that incriminating phone.

At the Woodsboro Sheriff's Department, Billy sits under harsh fluorescent lights as Sheriff Burke questions him. They seize his phone and quickly move to check his call log against the calls made to Casey and to Sidney. On paper, he looks bad: he appeared at the window moments after Sidney was chased, and he has a phone. But the technical records show none of the calls to Sidney's house came from Billy's number. He is released, but doubt lingers.

Sidney, meanwhile, stays at the Riley home--Tatum's house--under Dewey's protective eye. Tatum's room is a riot of posters, clothes, and color, a striking contrast to Sidney's more subdued space. They share nervous laughter and snack on junk food while the news blares from the living room. Gale Weathers' face fills the TV screen, coldly polished as she narrates the Woodsboro killings and revisits the Maureen Prescott case.

Outside the sheriff's station earlier, Sidney and Gale had their first real confrontation. Gale approached Sidney with a smile that didn't quite reach her eyes, microphone in hand. She reminded Sidney that her book argues Cotton Weary is innocent, that Maureen Prescott was having an affair with him and that it was consensual. She hints that Sidney's testimony--claiming she saw Cotton leaving the house wearing Maureen's coat, covered in blood--may have been mistaken.

Sidney, raw and grieving, hears this as an attack on her mother's memory and her own credibility. When Gale steps closer, pressing for a quote, Sidney snaps and punches her in the face, dropping the reporter to the pavement, blood appearing on Gale's lip. Cameras catch it all. It's a small moment of catharsis for Sidney, but it doesn't silence Gale. It only adds drama to Gale's coverage.

The next day at school, the atmosphere is feverish. The murders have already become gossip fodder. In the girls' bathroom, Sidney hides in a stall and overhears two classmates cruelly speculate that she might be behind the killings, that maybe she's gone crazy from her mother's death, that maybe Maureen wasn't the saint everyone thought she was. Their words sting--echoes of the whispers that followed Maureen's murder a year ago.

After they leave, the bathroom falls silent. Then Sidney hears a faint fabric whisper and sees, beneath the stall door, heavy black boots stepping quietly across the tile. The hem of a familiar black robe brushes the floor. She backs up, heart pounding, as the costumed figure climbs onto the partition, then drops down, lunging at her with a knife. Sidney screams and ducks, darting out of the stall, bolting from the bathroom before he can corner her. Whether it was a prankster in a Halloween‑store Ghostface costume or the real killer, she can't be sure. For her, the effect is the same: there is no safe place now.

Principal Himbry, enraged by students who run around the halls in Ghostface masks purchased from costume shops, confiscates masks and scissors them dramatically, threatening severe punishment. Later, long after the corridors have emptied and school has been dismissed early due to the threat, Himbry is alone in his office. He hears a noise. Thinking it's another prank, he stalks the halls, calling out, peering into closets. The tension ratchets up as he startles himself in a mirror, laughs nervously, then returns to his office.

The Ghostface killer is waiting.

In a burst of violence, the masked figure attacks, stabbing Himbry repeatedly. The principal's office, lined with trophies and photos, becomes a killing floor. Himbry dies alone, his body later moved and hung from the football field's goalpost, where it will be discovered as a gruesome spectacle for the town.

All the while, suspicion remains in flux. Billy Loomis has been released, but the seed is planted. Some police and students begin to eye Neil Prescott, Sidney's absent father, who cannot be reached and whose business trip suddenly looks suspicious. Gale Weathers continues to push the narrative that Cotton Weary, currently in prison, was framed. Underneath the present day, another murder--Maureen Prescott's--is being pulled back into the light.

At the local video store where he works, Randy holds court among shelves of VHS tapes, ranting about horror conventions as Stu needles him. They argue about who might be the killer. Randy says that in real life, the motive could be simple: "It's always the boyfriend," he suggests, pointing at Billy, or maybe "Stu's flipped out." The aisles of horror movies needling their debate become a visual chorus--Jason, Freddy, Michael Myers--slasher icons staring down at boys who talk like they're in a movie themselves.

Woodsboro High is shut down entirely after the principal's death. Sheriff Burke announces a curfew. The townsfolk scurry home as the sun goes down, porch lights flicking on early, blinds closing. In this charged atmosphere, Stu seizes the opportunity. With his parents out of town, he decides to throw a big party at his house to "blow off steam." Alcohol, horror movies, friends--what could go wrong?

Tatum and Sidney plan to go. Dewey, concerned, arranges to patrol the area, half cop, half big brother. Gale, ever the opportunist, decides the party is where the story will be. She convinces Kenny to drive their news van up near Stu's isolated, sprawling country home, a large, multi‑room house surrounded by woods and open field.

Before the night of the party, Sidney spends another night at Tatum's house. Gale drops by, all charm, trying to cozy up to Dewey under the guise of learning more about the investigation. Dewey is flattered by the attention. They flirt a little on the front porch under the yellow porch light, the sounds of late‑night TV drifting through the open window. Gale's interest is not purely romantic; she wants access, proximity, and Dewey, though earnest, doesn't fully grasp how much she'll use him.

The party at Stu Macher's house begins as a typical high‑school blowout. Students arrive with six‑packs, tapes, and gossip. Inside, the living room centers on a huge TV and a VCR, where John Carpenter's Halloween plays, its familiar score underscoring the night. Beer flows, couples make out, and kids shriek at jump scares on screen.

Gale and Kenny arrive in the van, parking discreetly nearby. Gale hides a tiny wireless camera on a shelf in Stu's living room, pointing it at the couch and crowd. Back in the van, Kenny sets up a monitor that displays the live feed. There's a 30‑second delay in the transmission, which Gale brushes off as a technical annoyance. They settle in to watch the party like voyeurs, waiting for something newsworthy to happen.

Inside, Randy seizes the attention of the room and deliver his famous set of "rules" for surviving a horror movie. Standing in front of the TV, slightly drunk, he lectures: you can never have sex; you can never drink or do drugs; you can never, ever say "I'll be right back." Everyone laughs. Stu, grinning, walks toward the kitchen, deliberately calling, "I'll be right back!" as a joke. The line plays like a gag and also a loaded gun--we know these rules matter.

In the middle of all this, Tatum heads to the garage to fetch more beer. The garage door rattles open, letting in the cool night air, the light buzzing overhead. Alone among the parked car, boxes, and a chest freezer, Tatum rummages in the fridge. When she tries to go back inside, the door to the kitchen is locked. She turns back toward the garage door, intending to go out and around, and stops.

The Ghostface killer stands there, half‑lit by the garage light, blocking the way. At first, Tatum laughs. She thinks it's someone at the party pulling a prank in the common Halloween costume. She plays along, joking flirtatiously, saying, "Ooh, Mr. Ghostface, I want to be in the sequel." She pelts the masked figure with beer bottles, still reading it as a game.

Then the killer steps closer and slashes at her arm, drawing real blood. Her amusement dies instantly, replaced by terror. She tries to flee through the side door. Locked. She runs to the garage door opener on the wall and hits the button. The heavy door begins to rumble upward. In a desperate bid, she struggles through the small dog/cat flap in the bottom of the garage door, fighting to wriggle her torso through. She gets stuck, half in, half out, arms flailing. Ghostface walks over, hits the garage door switch again. The door motor strains but keeps going, lifting Tatum up. Her body rises, wedged in the flap, her neck pressed tighter and tighter until, at the top of the frame, bone and cartilage give way. Her neck snaps under the pressure, and she hangs there limply, dead, like a broken doll dangling over the driveway.

Back inside, no one notices that Tatum is gone. This house, once a party, is slowly becoming a slaughterhouse.

As Halloween continues to play on TV, Billy Loomis arrives at the party, slipping in through the moving bodies. The music lowers as he pulls Sidney aside, talking softly. The general fear and suspicion swirling around them, his earlier arrest, the constant questioning of whether he could be the killer--these all hang between them. Sidney, rattled by everything, leads him upstairs into Stu's parents' bedroom, seeking a private place to talk.

In the relative quiet of the upstairs room, the party's noise muted, Billy and Sidney sit on the bed. He presses again, gently, about their relationship, about trust. He's been the prime suspect in her mind, but the evidence has seemed to clear him. Death is everywhere now. Sidney is tired of being frozen in trauma. She begins to open to him. They talk about how life isn't a movie, how there is no script to follow. In a small act of reclaiming her body and her choices, Sidney decides to have sex with Billy. They undress and make love on the bed, the moment intercut with scenes from Halloween downstairs. Her choice violates Randy's "never have sex" rule, knowingly subverting slasher tradition.

Downstairs, most of the partygoers suddenly bolt when someone gets word that Principal Himbry's body has been found hanging from the football field goalpost. Fueled by morbid curiosity and beer, they pile into cars and speed off to see it, leaving only a core group at Stu's house: Randy, still watching Halloween; Stu, wandering in and out; a few stragglers; and, upstairs, Sidney and Billy.

Gale and Dewey, having decided to poke around the area under the excuse of investigating the curfew, walk together down a dark country road near Stu's property. Dewey tries to impress Gale with his badge and talk about the case. Gale, holding a flashlight, looks more like a hunter than a companion. They stumble upon Neil Prescott's car hidden in the bushes, its presence ominous and unexplained. This discovery electrifies Gale--Neil's disappearance just became crucial. If the police believe Neil is behind the killings, the story becomes even bigger. Dewey, on the other hand, feels a fresh stab of worry for Sidney. Neil must be nearby, or he's being framed.

Inside Stu's living room, Randy's eyes stay glued to Halloween. He mumbles commentary at the screen, half to himself, half to anyone listening. On TV, Laurie Strode is being stalked by Michael Myers, and Randy shouts at her to "turn around," completely unaware that history is repeating behind him. In the news van, Kenny watches the delayed feed and laughs, until something on the monitor makes him sit up. On the screen, in the living room behind Randy, a door creaks and the Ghostface killer slips into view. Kenny realizes with creeping horror that the video feed is thirty seconds behind real time. Whatever he's seeing already happened.

He leans out of the van, yelling at Randy, trying to warn him, but timing betrays him. As he opens the side door, the real Ghostface appears outside, knife flashing. Kenny barely has time to react before the blade slices across his throat, opening him. Blood gushes over the van as he gurgles and collapses, dead.

Sidney and Billy, finished with sex, lie tangled on the bed, breaths slowing. The intimacy that was supposed to be a safe harbor turns out to be anything but. Suddenly, the bedroom door bursts open. Ghostface rushes in. He slashes wildly, and Billy is struck, blood blossoming over his shirt as he staggers and falls, apparently mortally wounded. Sidney screams, half‑dressed, and flees, racing through the upstairs hallway.

She stumbles down the stairs, across the now‑sparsely populated living room, and out toward the front door. The killer is close behind. She escapes the house, sprinting toward the news van in the driveway. Inside, she finds no help--Kenny's body slumped, throat cut, blood everywhere. She scrambles into the driver's seat, trying to start the engine. Suddenly Kenny's corpse slides forward across the windshield, face smeared with blood. Sidney shrieks and wrenches the wheel, the van careening off the road and slamming into a tree, the collision jarring her.

Meanwhile, Gale has doubled back toward the house to find Kenny and her equipment. She climbs into the van, sees blood, and realizes something is terribly wrong. She throws the vehicle into gear and roars down the narrow driveway, but Sidney, dazed from the crash, staggers into her path. Gale jerks the wheel, swerving to avoid hitting her, and the van goes off the road, crunching into a tree. Gale's head smashes against the interior. She slumps, apparently unconscious or worse, the front of the van crumpled.

Sidney, bruised and more alone than ever, crawls away from the wreckage and back toward Stu's house. On the front porch, under pale light, she finds Dewey stumbling out of the doorway. There is a knife protruding from his back, his uniform stained with blood. He reaches toward her and collapses off the porch, collapsing into the yard. Sidney grabs his gun, the steel heavy in her trembling hands. She backs into the house, gun raised, trying to find somewhere defensible to hide.

Inside, Randy appears at a side door, breathless, yelling for her to let him in. Stu appears at another, equally frantic, both of them shouting that the other is the killer. Sidney points the gun back and forth between them. Paranoia, betrayal, and fear swirl. Randy says, "He's gone mad!" Stu says the same about Randy. Sidney makes an agonizing choice. She locks them both out, slamming and bolting the door, refusing to trust either.

Upstairs, she stumbles into a hallway and finds Billy. He's alive, or appears to be, blood‑soaked but conscious, leaning heavily against the wall. His voice is weak. He reaches for her, and she, in shock, hands him Dewey's gun. Billy, trembling, moves to the front door and opens it, letting Randy in. Randy limps in, panicked, saying, "Stu's gone mad!" On the word mad, Billy turns, aims the gun, and shoots Randy in the shoulder.

The crack of the shot echoes in the foyer. Randy falls, screaming. Sidney gapes at Billy, betrayal flooding her. His expression transforms. The wounded, innocent boyfriend is gone, replaced by a cold, predatory stare. He raises the gun slightly, waggles it, and quotes Psycho with a dark, delighted glint: "We all go a little mad sometimes."

From behind Sidney, Stu steps into view, blocking her path, grinning, calm in the chaos. The two boys stand together now, united by something finally visible. Stu pulls a voice changer from his pocket, holds it to his mouth, and speaks into it, mimicking the Ghostface phone voice. The truth drops like a stone: there are two killers. Billy Loomis and Stu Macher have been sharing the mask and robe, sharing the voice, sharing the knife.

They lead Sidney into the kitchen, kicking Randy's bleeding form aside like an afterthought. On the counter lies an arsenal of their tools: the Ghostface mask and robe, the hunting knife, the voice changer, a portable phone. They theatrically lay out their story, like directors walking Sidney through the third act of a horror script.

Billy's voice trembles not with fear but with exhilaration. He explains that they have Sidney's father, Neil Prescott, bound and gagged in a closet. They open a pantry door to reveal Neil tied to a chair, tape over his mouth, eyes wild with panic. They have his wallet, his car, his phone records. Their plan is to kill Sidney and Neil and frame Neil as the mastermind of the entire murder spree, including Casey, Steve, Himbry, Tatum, Kenny, and everyone else. They'll stab themselves just enough to look like they barely survived their father's rampage.

Sidney, bound and bruised, sputters that they're insane. Billy smiles thinly. He says that in the movies, killers always have some big motive, some tragic backstory, but that real life is scarier when there is no motive. Then, as if he can't resist, he reveals his motive anyway.

He tells Sidney that her mother, Maureen Prescott, had an affair with his father, Hank Loomis. That affair tore his family apart. His mother left, abandoning him. He blames Maureen for his mother's disappearance and emotional ruin. In revenge, a year ago, Billy and Stu murdered Maureen Prescott and framed Cotton Weary for it, using Maureen's reputation and Sidney's testimony to send Cotton to prison. Tonight's carnage is the sequel, a bloody follow‑up to that first, unseen crime. Everything Sidney believed about her mother's murder--the justice, the closure--has been a lie.

Stu, giggling and jittery, chimes in, delighting in how they're staging everything. They talk about the killings the way Randy talks about horror plots, except this time, the script is real and they're holding the pen. The language of movies has become the language of their violence.

To complete the framing, they must become victims too. In a grotesque, ritualistic scene, Billy hands Stu the knife and orders him to stab him. Stu hesitates, drunk on adrenaline and fear, then plunges the blade into Billy's side, drawing a controlled amount of blood. Billy grimaces, then smiles, takes back the knife, and slices into Stu's torso in return. Once, twice. The stabs are supposed to be superficial, but Stu is less tough than he thinks. Blood pours heavily from his wounds. His joking slows. His face goes pale.

Billy, bleeding but still composed, rehearses their story aloud: Neil snapped on the anniversary of his wife's death, kidnapped his daughter, killed her friends, then tried to kill them. They, the brave survivors, barely stopped him. It's all so neat, so cinematic.

Then the script goes off the rails.

In the middle of this gory recitation, Gale staggers into the kitchen doorway, battered but alive, Dewey's gun in her hands. Her hair is mussed, her suit torn, but the reporter is still there. She aims the gun at Billy, voice shaking but determined, and quips something about "an ending to your story." She pulls the trigger.

Nothing happens.

Billy turns, eyes dropping to the weapon, and realizes the safety is still on. He grins. In a heartbeat, he lunges, slams into Gale, and knocks her to the floor. The gun skitters away. Gale groans, her head cracking against the floor tile. Billy reclaims control, seething.

In the chaos, Sidney vanishes. When Billy and Stu look up, she's gone from her corner. The kitchen suddenly feels larger, darker, full of lurking threat. The hunters are momentarily the hunted. Somewhere in the house, the phone rings.

Billy and Stu split up. Stu, bleeding more heavily now, grabs the portable phone. His swagger is gone, replaced by a woozy, panicked edge. The phone rings again, echoing through the quiet house. He answers. The voice that greets him is the Ghostface voice--but this time, it's Sidney using the voice changer. She has slipped on part of the costume and taken the device, turning the killers' own tactics against them.

From her hiding place, she taunts Stu, asking how it feels. On the phone, Stu starts to unravel. He's bleeding out and finally realizing he may not get away with this. "I think I'm dying here, man," he whimpers to Billy at one point. When Sidney mocks him about what his parents will say, he whines, "My mom and dad are gonna be so mad at me!"--a darkly comic line that reveals the pathetic, adolescent core under his brutality.

Billy, enraged and more focused, stalks the house with the knife, smashing doors, ripping curtains aside, searching for Sidney. Stu stumbles into the living room, spinning in circles, disoriented, trying to find her. The party house is now an empty, echoing slaughter scene, bodies tucked away, blood smeared on walls and doors.

Sidney ambushes Stu in the kitchen. Wearing the mask, she bursts from hiding, tackling him. They grapple violently, slipping in blood. She grabs any object she can--the phone, utensils, anything--to fend off his wild swings. At one point, she slams the phone into his head, the impact ringing. He yelps, "You hit me with the phone, you bitch!" in a tone equal parts angry and incredulous, another moment of absurd humor amid horror. But he's faltering. He's lost too much blood.

Sidney's eyes land on the large television set sitting on the kitchen counter, its cathode‑ray tube heavy and solid. As Stu lurches up from the floor near the counter, she shoves the TV with all her remaining strength. It topples forward, crashing down onto his head. Glass shatters, electricity crackles, and the weight smashes his skull. Stu jerks once, then lies still under the broken TV, dead.

One killer down.

Billy, hearing noise in the kitchen, runs in, knife ready. He finds Stu's body under the TV. Sidney, slipping out of her partial costume, emerges to confront him. They fight brutally, a close‑quarters brawl fueled by grief and fury. He slashes at her; she dodges, kicks, claws at his eyes, grabs at whatever is within reach to hit him with. They crash into cabinets, onto countertops. This is not a choreographed fight; it's messy survival.

Then Gale appears again, staggering into the room, Dewey's gun in hand once more. This time, the safety is off. She fires, the shot hitting Billy in the shoulder or torso, knocking him backward. He collapses to the floor, seemingly dead or dying.

Sidney breathes hard, scanning the room. Randy crawls in, clutching his shoulder, blood on his shirt but alive. He looks around at the bodies, the destruction, then at Billy's still form on the floor. His horror‑movie brain can't help himself. He warns Sidney and Gale: in horror movies, this is always the moment when the supposedly dead killer suddenly springs back to life for one last scare.

The three of them creep closer to Billy's body. Sidney, a gun in her hand now, leans over him. For a second, he is just a corpse, a boy who orchestrated all this carnage and now lies still. Then, with a burst of energy, Billy's eyes snap open and he lunges up, roaring, the final jump scare manifest.

Sidney doesn't flinch. She raises the gun to his forehead and pulls the trigger. The bullet tears through his skull. Billy Loomis drops, definitively dead, blood pooling on the kitchen floor.

Dawn begins to creep toward Woodsboro as police sirens wail in the distance. The night of terror finally cracks open to morning. Officers flood the Macher property. They find Neil Prescott alive in the closet where Billy and Stu bound and gagged him, shaking and stunned but physically intact. They cut his ropes and peel tape from his mouth. He rushes to Sidney, pulling her into his arms. She's covered in blood, some of it hers, most of it others'. The weight of everything--her mother's real killers, the wrongful imprisonment of Cotton Weary, the murders of her friends--presses down on her, but she's standing.

Dewey Riley, pale and weak, is carried out on a stretcher, the knife wound in his back bandaged. For a moment, Gale, watching, looks almost relieved. Dewey, the bumbling deputy who tried so hard, is alive. Randy, his arm in a makeshift sling, sits on the porch steps, grimacing but talking, his encyclopedic knowledge of horror finally having helped him survive.

News vans and reporters swarm the area as the sun rises over the shattered shards of Stu's house. Once again, cameras turn the suffering of Woodsboro into broadcast content. But this time, Gale Weathers stands not as a detached, opportunistic outsider, but as a survivor too. Bloodied, bruised, hair tousled, she faces a camera as it goes live, delivering a breathless, improvised report about the massacre in Woodsboro, about the revelation that the killers were high‑school students Billy Loomis and Stu Macher, about the rescue of Neil Prescott and the wounded but living deputy and teens.

Behind her, yellow police tape flutters. Gurneys roll victims to waiting ambulances. Officers move in and out of the ruined house. The sky is a soft, indifferent blue. Gale's voice continues over the imagery, a final commentary on a town that has woken from its nightmares to find they were real.

Sidney stands nearby with her father, watching the chaos and the cameras, framed by the early morning light. The girl who began the story haunted by her mother's unsolved questions and by a town's gossip is now the final girl who has fought back, solved the mystery, and survived. There is no twist left unrevealed: Billy and Stu killed Maureen. They framed Cotton Weary. They murdered Casey, Steve, Principal Himbry, Tatum, and Kenny. They stabbed Dewey, shot Randy, nearly killed Gale. They wanted to write the perfect horror movie, and in the end they became the villains whose story ends with a bullet through the head and a TV crushed into bone.

The camera pulls back on the scene as Gale's live voiceover continues, the sounds of sirens and morning birds overlapping. Woodsboro, once sleepy, is now a crime scene. The night is over. The bodies are counted. Sidney Prescott, bruised but unbroken, walks forward into the new day, every secret exposed, every twist revealed, no more illusions about monsters wearing the faces of boys she thought she knew.

What is the ending?

In the ending of "Scream," Sidney Prescott confronts the killers, Billy Loomis and Stu Macher, in a climactic showdown. After a tense battle, Sidney manages to outsmart them, ultimately killing Billy and leaving Stu incapacitated. The film concludes with Sidney surviving the ordeal, but the trauma of the events lingers.

As the final act unfolds, the tension escalates in the dimly lit halls of Woodsboro High School. Sidney Prescott, having already endured the horrors of the Ghostface killer, finds herself cornered in the house of her friend, Tatum. The atmosphere is thick with dread as she realizes that the killer is not just a faceless entity but someone she knows.

The scene shifts to the living room, where the party is in full swing, unaware of the impending danger. The camera pans to reveal the iconic Ghostface mask, signaling the return of the killer. As the partygoers laugh and drink, the audience feels the impending doom. The phone rings, and Sidney answers, only to hear the chilling voice of Ghostface taunting her. The tension mounts as she realizes that her friends are in danger.

In a frantic attempt to escape, Sidney runs through the house, her heart racing. She encounters Tatum, who is tragically killed in the garage, crushed by the garage door in a horrifying moment that underscores the brutality of the killer. Sidney's fear transforms into determination as she fights to survive.

The climax reaches its peak when Sidney confronts Billy and Stu in the living room. The two reveal their twisted motivations, with Billy confessing that he killed Sidney's mother a year prior, driven by a desire for revenge. The emotional weight of this revelation hits Sidney hard, but she steels herself for the fight.

In a desperate struggle, Sidney uses her wits to turn the tables on her attackers. She manages to stab Billy, leaving him incapacitated. However, the fight is not over; Stu, still alive, attempts to attack her. In a final act of defiance, Sidney uses the very tools of horror against them, ultimately defeating both killers.

As the police arrive, the aftermath of the chaos begins to settle. Sidney stands amidst the wreckage of her friends and the horror that unfolded, her face a mixture of relief and trauma. Dewey, the local deputy, is injured but alive, and Gale Weathers, the ambitious reporter, is left to document the aftermath.

The film closes with a haunting sense of survival, as Sidney walks away from the house, forever changed by the events. The fate of the main characters is sealed: Sidney survives, but the emotional scars remain; Billy and Stu are dead, their reign of terror ended, but the impact of their actions lingers in the air, leaving the audience with a chilling reminder of the fragility of safety and the darkness that can lurk within familiar faces.

Is there a post-credit scene?

The movie "Scream," produced in 1996, does not have a post-credit scene. The film concludes with a tense and dramatic climax, where the main characters, Sidney Prescott, Gale Weathers, and Dewey Riley, confront the masked killer, Ghostface. After the final confrontation, the film wraps up with a sense of resolution, leaving the audience with the chilling aftermath of the events that transpired. The credits roll without any additional scenes or content following them.

Who is the killer in Scream?

The killer in Scream is revealed to be Billy Loomis and Stu Macher. They are both high school students who orchestrate the murders as part of a twisted plan to create their own horror movie.

What motivates Billy Loomis to kill?

Billy Loomis is motivated by a desire for revenge against Sidney Prescott, as he believes she is responsible for the breakup of his parents' marriage. His obsession with horror movies also fuels his actions, as he wants to create a real-life horror scenario.

How does Sidney Prescott's character evolve throughout the film?

Sidney Prescott starts as a typical high school girl dealing with the trauma of her mother's murder. As the film progresses, she becomes more resilient and resourceful, ultimately confronting her fears and fighting back against the killers.

What role does the character Randy Meeks play in the story?

Randy Meeks serves as the horror movie aficionado who provides comic relief and meta-commentary on slasher film tropes. His knowledge of horror films becomes crucial as he tries to warn his friends about the rules of surviving a horror movie.

What is the significance of the phone calls in Scream?

The phone calls in Scream serve as a catalyst for the tension and fear in the film. They begin with a chilling conversation between Casey Becker and the killer, establishing the tone of the movie. The calls symbolize the invasion of privacy and the omnipresence of danger, as the killer uses them to taunt and manipulate his victims.

Is this family friendly?

"Scream," produced in 1996, is not considered family-friendly due to its intense themes and graphic content. Here are some potentially objectionable or upsetting aspects that may affect children or sensitive viewers:

-

Graphic Violence: The film features several scenes of brutal violence, including stabbings and murders, which are depicted in a visceral manner.

-

Murder and Death: The central plot revolves around a serial killer targeting teenagers, leading to multiple deaths that are portrayed with emotional weight and horror.

-

Strong Language: The dialogue includes frequent use of profanity and crude language, which may be inappropriate for younger audiences.

-

Sexual Content: There are scenes that involve sexual situations and innuendos, which may not be suitable for children.

-

Psychological Tension: The film creates a pervasive atmosphere of fear and suspense, which can be distressing for sensitive viewers.

-

Themes of Betrayal and Trust: The narrative explores themes of betrayal among friends, which can evoke feelings of anxiety and discomfort.

Overall, "Scream" is designed for a mature audience and contains elements that could be upsetting for children or those who are sensitive to horror and violence.